While the Wilburns submitted the highest price at a real estate auction, it was below the reserve price set by the bank who was auctioning the property. They nevertheless sought to enforce a right to the property. The Dallas Court affirmed a take-nothing verdict for the defendants. As to the auctioneer’s actual authority, the Court noted the instructions about reserve price in the “Agreement to Conduct Auction Sale.” As to his apparent authority, the Court noted the auctioneer’s statements at the start of the auction and the Wilburns’ signatures on two cards that said what a reserve price was and referenced the auctioneer’s contract: “None of the bank’s actions or inactions clothed the auctioneer with the indicia of authority to sell the Property at a price below the reserve without Valliance’s consent.” Wilburn v. Valliance Bank, No. 05-14-00965-CV (Dec. 21, 2015) (mem. op.)

While the Wilburns submitted the highest price at a real estate auction, it was below the reserve price set by the bank who was auctioning the property. They nevertheless sought to enforce a right to the property. The Dallas Court affirmed a take-nothing verdict for the defendants. As to the auctioneer’s actual authority, the Court noted the instructions about reserve price in the “Agreement to Conduct Auction Sale.” As to his apparent authority, the Court noted the auctioneer’s statements at the start of the auction and the Wilburns’ signatures on two cards that said what a reserve price was and referenced the auctioneer’s contract: “None of the bank’s actions or inactions clothed the auctioneer with the indicia of authority to sell the Property at a price below the reserve without Valliance’s consent.” Wilburn v. Valliance Bank, No. 05-14-00965-CV (Dec. 21, 2015) (mem. op.)

Monthly Archives: December 2015

Tervita LLC unsuccessfully disputed Sutterfield’s workers compensation claim in a contested hearing; afterwards, Sutterfield sued Tervita for various torts relating to its handling of his claim. The trial court denied Tervita’s motion to dismiss under the new Texas anti-SLAPP statute. The Dallas Court of Appeals reversed as to Sutterfield’s claims based on Tervita’s participation in the agency hearing, concluding that those claims were based on Tervita’s exercise of its right to petition. It otherwise affirmed, concluding that Sutterfield’s claims about a hostile work environment and wrongful discharge “are based on Tervita’s actions and statements outside of the TDI-WC proceeding.” Tervita LLC v. Sutterfield, No. 05-15-00479-CV (Dec. 18, 2015).

Tervita LLC unsuccessfully disputed Sutterfield’s workers compensation claim in a contested hearing; afterwards, Sutterfield sued Tervita for various torts relating to its handling of his claim. The trial court denied Tervita’s motion to dismiss under the new Texas anti-SLAPP statute. The Dallas Court of Appeals reversed as to Sutterfield’s claims based on Tervita’s participation in the agency hearing, concluding that those claims were based on Tervita’s exercise of its right to petition. It otherwise affirmed, concluding that Sutterfield’s claims about a hostile work environment and wrongful discharge “are based on Tervita’s actions and statements outside of the TDI-WC proceeding.” Tervita LLC v. Sutterfield, No. 05-15-00479-CV (Dec. 18, 2015).

The Hales sued their homebuilder for fraud and violation of the DTPA, alleging serious problems with the foundation of their Rockwall home (right). They substantially succeeded at trial, and the Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed in large part in Bishop Abbey Homes, Ltd. v. Hale, No. 05-14-00137-CV (Dec. 16, 2015) (mem. op.) In particular, the Court affirmed as to limitations – a significant issue in this long-simmering dispute – noting that “each time the Hales raised a concern about the foundation, they were assured by one of appellants’ experts that the foundation was not the cause of the problems the Hales observed.” The court also affirmed as to sufficiency challenges to liability, several claims of improper closing argument, and a challenge to the the basis of the exemplary damages award based on constitutional and Kraus factors. The court requested a remittitur as to (a) mental anguish damages (for sufficiency reasons) above $208,856 per plaintiff; and (b) a portion of the additional/exemplary damages award, based on the applicable cap and the conclusion that the total award “exceeds the guidelines set forth in [Bennett v. Reynolds, 315 S.W.3d 867 (Tex. 2010)] and [Tony Gullo Motors I, LP v. Chapa, 212 S.W.3d 299 (Tex. 2006)] for the type of harm suffered by the Hales as a result of appellants’ conduct.”

The Hales sued their homebuilder for fraud and violation of the DTPA, alleging serious problems with the foundation of their Rockwall home (right). They substantially succeeded at trial, and the Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed in large part in Bishop Abbey Homes, Ltd. v. Hale, No. 05-14-00137-CV (Dec. 16, 2015) (mem. op.) In particular, the Court affirmed as to limitations – a significant issue in this long-simmering dispute – noting that “each time the Hales raised a concern about the foundation, they were assured by one of appellants’ experts that the foundation was not the cause of the problems the Hales observed.” The court also affirmed as to sufficiency challenges to liability, several claims of improper closing argument, and a challenge to the the basis of the exemplary damages award based on constitutional and Kraus factors. The court requested a remittitur as to (a) mental anguish damages (for sufficiency reasons) above $208,856 per plaintiff; and (b) a portion of the additional/exemplary damages award, based on the applicable cap and the conclusion that the total award “exceeds the guidelines set forth in [Bennett v. Reynolds, 315 S.W.3d 867 (Tex. 2010)] and [Tony Gullo Motors I, LP v. Chapa, 212 S.W.3d 299 (Tex. 2006)] for the type of harm suffered by the Hales as a result of appellants’ conduct.”

In the mandamus case of In re Fort Apache Energy Inc., the relators sought relief from a trial setting in Dallas County, alleging that it interfered with the dominant jurisdiction (and slightly later trial setting) of the Kendall County Court. No. 05-15-00159-CV (Dec. 16, 2015). The Dallas Court of Appeals denied the petition, finding that the setting did not “amount[] to the kind of direct interference . . . that warrants mandamus relief under currently governing law.” (citing, inter alia, Abor v. Black, 695 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1985) (orig. proceeding). In a classic disagreement about the scope and role of mandamus proceedings, a dissent would grant relief, arguing that “refusal to correct the trial court’s clear abuse of discretion by mandamus presents a strong likelihood of wasted public and private resources alike.” The Texas Supreme Court has since accepted a mandamus petition in, and set oral argument for, a similar case, also from Dallas.

In the mandamus case of In re Fort Apache Energy Inc., the relators sought relief from a trial setting in Dallas County, alleging that it interfered with the dominant jurisdiction (and slightly later trial setting) of the Kendall County Court. No. 05-15-00159-CV (Dec. 16, 2015). The Dallas Court of Appeals denied the petition, finding that the setting did not “amount[] to the kind of direct interference . . . that warrants mandamus relief under currently governing law.” (citing, inter alia, Abor v. Black, 695 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1985) (orig. proceeding). In a classic disagreement about the scope and role of mandamus proceedings, a dissent would grant relief, arguing that “refusal to correct the trial court’s clear abuse of discretion by mandamus presents a strong likelihood of wasted public and private resources alike.” The Texas Supreme Court has since accepted a mandamus petition in, and set oral argument for, a similar case, also from Dallas.

One Technologies (“OT”) sued Profini ty and a former OT employee for breach of a noncompetition agreement. Profinity counterclaimed for violations of the Texas antitrust statute. The jury found against OT and for Profinity; the trial judge adopted the verdict as to OT’s claims and granted JNOV on Profinity’s. The Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed, changing only the basis for resolution of the antitrust claim. Profinity LLC v. One Technologies, LP, No. 05-14-00403-CV (Dec. 17, 2015) (mem. op.)

ty and a former OT employee for breach of a noncompetition agreement. Profinity counterclaimed for violations of the Texas antitrust statute. The jury found against OT and for Profinity; the trial judge adopted the verdict as to OT’s claims and granted JNOV on Profinity’s. The Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed, changing only the basis for resolution of the antitrust claim. Profinity LLC v. One Technologies, LP, No. 05-14-00403-CV (Dec. 17, 2015) (mem. op.)

As to OT’s claim, the Court found no conclusive proof the element of damage, noting that Profinity’s damages expert had squarely clashed with OT’s expert at trial. As to the antitrust claims, the Court expressed considerable skepticism about Profinity’s damages model, which calculated the value of lost customers nationwide. Under Coca-Cola Co. v. Harmar Bottling Co., 218 S.W.3d 671 (Tex. 2006), because “remedying extraterritorial injury . . . would provide no benefit to consumers ‘in state,'” even allegations of anticompetitive conduct in Texas toward a company based in Texas are likely not actionable under the Texas statute. The Court did not rule on this basis, however, instead finding a lack of jurisdiction under the Noerr-Pennington doctrine, as the alleged anticompetitive conduct focused on “conduct ‘incidental’ to the prosecution of a lawsuit respecting [antitrust] redress.” (citing Noell v. City of Carrollton, 431 S.W.3d 682, 708 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2014, pet. denied).

While otherwise affirming the plaintiffs’ victory in an easement dispute, the Dallas Court of Appeals struck a portion of the trial court’s declaratory judgment related to the legal rights associated with that easement. The Court found no request for judgment on that matter in the plaintiffs’ live pleading or summary judgment motion, and also found that general discussion of the applicable city regulations had been offered for other purposes. The Court reminded: “[A]n issue is not tried by consent when evidence relevant to the unpleaded issue is also relevant to a pleaded issue because admitting that evidence would not be calculated to elicit an objection and its admission would not prove the parties’ ‘clear intent’ to try the unpleaded issue.” United Services Pyramid Group v. Hurt, Noi. 05-14-00108-CV (Dec. 7, 2015) (mem. op.)

While otherwise affirming the plaintiffs’ victory in an easement dispute, the Dallas Court of Appeals struck a portion of the trial court’s declaratory judgment related to the legal rights associated with that easement. The Court found no request for judgment on that matter in the plaintiffs’ live pleading or summary judgment motion, and also found that general discussion of the applicable city regulations had been offered for other purposes. The Court reminded: “[A]n issue is not tried by consent when evidence relevant to the unpleaded issue is also relevant to a pleaded issue because admitting that evidence would not be calculated to elicit an objection and its admission would not prove the parties’ ‘clear intent’ to try the unpleaded issue.” United Services Pyramid Group v. Hurt, Noi. 05-14-00108-CV (Dec. 7, 2015) (mem. op.)

Defendant won summary judgment, with a combination of no-evidence and traditional grounds, on fraudulent transfer claims. Renate Nixdorf v. Midland Investors LLC, No. 05-14-01258-CV (Dec. 8, 2015) (mem. op.) The Dallas Court of Appeals reversed, finding problems with what defensive matters were appropriately addressed by a no evidence summary judgment motion and what specific transactions were at issue, as well as proof of “reasonably equivalent value” that was conclusory.

Defendant won summary judgment, with a combination of no-evidence and traditional grounds, on fraudulent transfer claims. Renate Nixdorf v. Midland Investors LLC, No. 05-14-01258-CV (Dec. 8, 2015) (mem. op.) The Dallas Court of Appeals reversed, finding problems with what defensive matters were appropriately addressed by a no evidence summary judgment motion and what specific transactions were at issue, as well as proof of “reasonably equivalent value” that was conclusory.

Cross moved for summary judgment on limitations, submitting this affidavit: “My name is John K. Cross. I am at least 18 years of age and of sound mind. I have personal knowledge of the facts alleged in Defendant’s Second Motion for Summary Judgement. I hereby swear that the following statements in support of Defendant’s Second Motion for Summary Judgment are true and correct. The mortgage at issue in this case was a secondary mortgage on a home I owned in Massachusetts. The primary holder foreclosed on the property, and it was sold at foreclosure sale on July 14, 2010 per the correspondence I received from the mortgage holder’s attorney on May 28, 2010.”

Cross moved for summary judgment on limitations, submitting this affidavit: “My name is John K. Cross. I am at least 18 years of age and of sound mind. I have personal knowledge of the facts alleged in Defendant’s Second Motion for Summary Judgement. I hereby swear that the following statements in support of Defendant’s Second Motion for Summary Judgment are true and correct. The mortgage at issue in this case was a secondary mortgage on a home I owned in Massachusetts. The primary holder foreclosed on the property, and it was sold at foreclosure sale on July 14, 2010 per the correspondence I received from the mortgage holder’s attorney on May 28, 2010.”

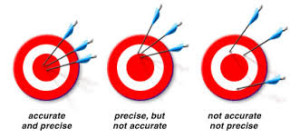

Unfortunately for Cross, “[a]n affidavit that, on its face, establishes the affiant’s lack of personal knowledge is a defect of substance that may be raised for the first time on appeal.” Here, “Cross’s affidavit affirmatively demonstrates his lack of personal knowledge on its face with respect to the date of the foreclosure sale. Cross attested only to what the May 28th letter told him.” Old Republic Ins Co. v. Cross, No. 05 14-01204-CV (Dec. 7, 2015) (mem. op.) (The opinion is not completely clear on the identity of the parties, but it appears that the “mortgage holder” in the letter was not Cross’s party-opponent in this litigation, so that doctrine was not discussed.)

Dickson, an attorney, alleged interference with his contingent fee contract that led to the abandonment of a promising appeal. The Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed summary judgment for the defense, noting: “Dickson’s summary judgment response below that the appeal was a ‘slam dunk’ is conclusory because it does not provide the underlying facts to support it.” Dickson v. American Electric Power, Inc., No. 05-14-00690-CV (revised Jan. 15, 2016) (mem. op.)

Highland Capital won a judgment for over $20 million based on the alleged breach of a contract by RBC Capital to sell a package of notes. RBC Capital Markets, LLC v. Highland Capital Management, LP, No. 05-13-00948-CV (Dec. 4, 2015) (mem. op.) The Dallas Court of Appeals reversed, finding no enforceable contract. The Court first reviewed the protean doctrines of judicial admissions and judicial estoppel, ultimately concluding that statements made by RBC in other litigation were not preclusive in this case, noting that RBC did not ultimately prevail in the other matter. It then rejected Highland’s argument that a contract was formed when the parties agreed upon “price and principal,” noting that RBC’s acceptance was expressly subject to further documentation (specifically, a written trade confirmation and purchase agreement). The Court noted that, as alleged by Highland, the claimed breach involved matters that remained to be resolved in those subsequent documents. (Another “conditional agreement” case is discussed today on sister blog 600Camp.)

Highland Capital won a judgment for over $20 million based on the alleged breach of a contract by RBC Capital to sell a package of notes. RBC Capital Markets, LLC v. Highland Capital Management, LP, No. 05-13-00948-CV (Dec. 4, 2015) (mem. op.) The Dallas Court of Appeals reversed, finding no enforceable contract. The Court first reviewed the protean doctrines of judicial admissions and judicial estoppel, ultimately concluding that statements made by RBC in other litigation were not preclusive in this case, noting that RBC did not ultimately prevail in the other matter. It then rejected Highland’s argument that a contract was formed when the parties agreed upon “price and principal,” noting that RBC’s acceptance was expressly subject to further documentation (specifically, a written trade confirmation and purchase agreement). The Court noted that, as alleged by Highland, the claimed breach involved matters that remained to be resolved in those subsequent documents. (Another “conditional agreement” case is discussed today on sister blog 600Camp.)

Does a limitation of liability provision include gross negligence claims? This basic question of contract drafting finds surprisingly little answer in Texas authority. A recent article by LTPC attorneys David Coale and Mallory Biblo summarizes the opinions and where the Dallas Court of Appeals falls.

Does a limitation of liability provision include gross negligence claims? This basic question of contract drafting finds surprisingly little answer in Texas authority. A recent article by LTPC attorneys David Coale and Mallory Biblo summarizes the opinions and where the Dallas Court of Appeals falls.

Not too early . . . Gast v. Tinsley, No. 05-15-00498-CV (Nov. 24, 2015, mem. op.) (unresolved claims remained in the trial court against other defendants)

Not too early . . . Gast v. Tinsley, No. 05-15-00498-CV (Nov. 24, 2015, mem. op.) (unresolved claims remained in the trial court against other defendants)

Not too late . . . In re: S.A.W., No. 05-15-00876-CV (Nov. 25, 2015, mem. op.) (notice untimely after nunc pro tunc order revised judgment to a significantly earlier date)