The TCPA says: “If a legal action is based on, relates to, or is in response to a party’s exercise of the right of free speech, right to petition, or right of association, that party may file a motion to dismiss the legal action.” Encore Enterprises, Inc. v. Shetty involved a Sabine Pilot claim in which the plaintiff alleged wrongful termination after raising concerns about tax issues. The Fifth Court affirmed the denial of the defendant corporation’s motion to dismiss, observing: “Here, Encore’s motion to dismiss did not argue that Shetty’s lawsuit is based on, relates to, or is in response to Encore’s communications about Shetty. Rather, Encore argued that Shetty’s lawsuit is based on Shetty’s communications to Encore about allegedly illegal activities that Encore maintains are matters of public concern.” No. 05-18-00511-CV (April 29, 2019) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

The TCPA says: “If a legal action is based on, relates to, or is in response to a party’s exercise of the right of free speech, right to petition, or right of association, that party may file a motion to dismiss the legal action.” Encore Enterprises, Inc. v. Shetty involved a Sabine Pilot claim in which the plaintiff alleged wrongful termination after raising concerns about tax issues. The Fifth Court affirmed the denial of the defendant corporation’s motion to dismiss, observing: “Here, Encore’s motion to dismiss did not argue that Shetty’s lawsuit is based on, relates to, or is in response to Encore’s communications about Shetty. Rather, Encore argued that Shetty’s lawsuit is based on Shetty’s communications to Encore about allegedly illegal activities that Encore maintains are matters of public concern.” No. 05-18-00511-CV (April 29, 2019) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

Monthly Archives: April 2019

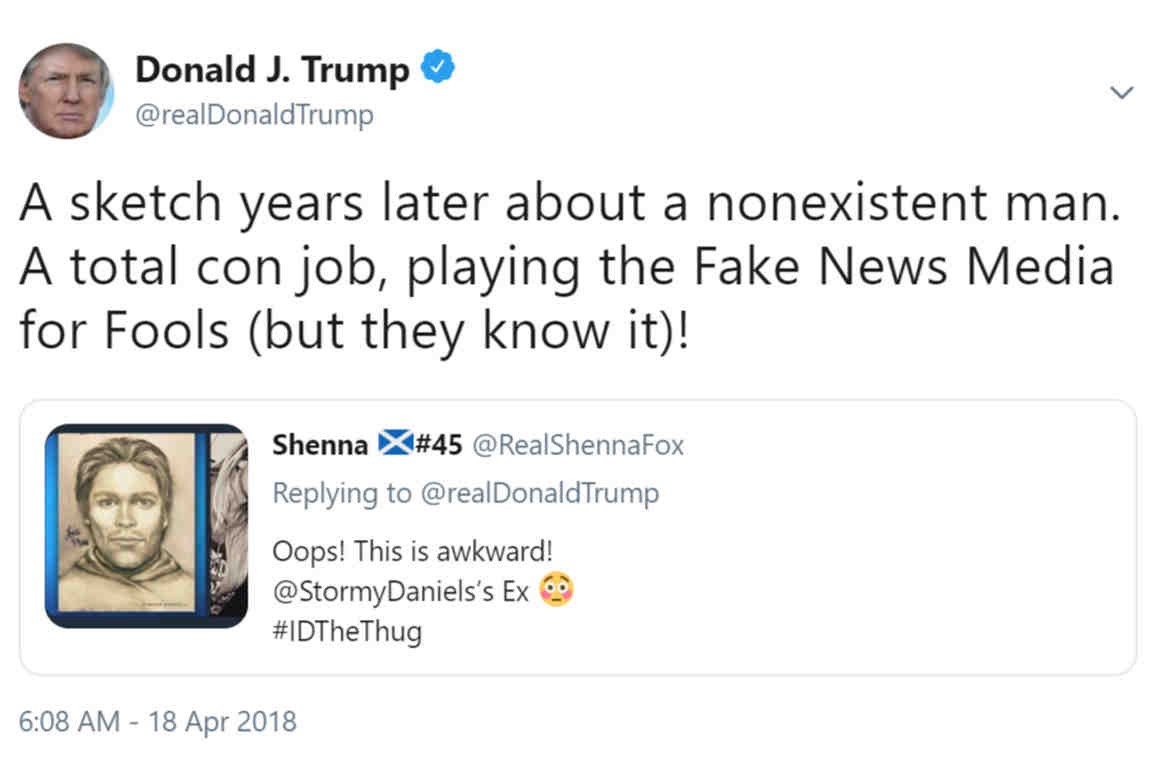

The Texas anti-SLAPP statute has generated an enormous amount of litigation and commentary, especially with the Legislature in session and actively considering amendments. Interestingly, one of the most successful defendants to invoke this statute is President Trump, who used it last year in California federal court to obtain dismissal of a defamation claim about the above Tweet, as well as a substantial award of attorneys’ fees. The district court’s opinion is interesting reading on the merits, as well on choice-of-law and the Ninth Circuit’s treatment of the underlying Erie issue.

The Texas anti-SLAPP statute has generated an enormous amount of litigation and commentary, especially with the Legislature in session and actively considering amendments. Interestingly, one of the most successful defendants to invoke this statute is President Trump, who used it last year in California federal court to obtain dismissal of a defamation claim about the above Tweet, as well as a substantial award of attorneys’ fees. The district court’s opinion is interesting reading on the merits, as well on choice-of-law and the Ninth Circuit’s treatment of the underlying Erie issue.

In its introduction to a comprehensive discussion of attorneys’-fee recovery, the Texas Supreme Court said: “It should have been clear from our opinions in [three earlier case] that we intended the lodestar analysis to apply to any situation in which an objective calculation of reasonable hours worked times a reasonable rate can be employed. We reaffirm today that the fact finder’s starting point for calculating an attorney’s fee award is determining the reasonable hours worked multiplied by a reasonable hourly rate, and the fee claimant bears the burden of providing sufficient evidence on both counts.” Rohrmoos Venture v. UTSW DVA Healthcare LLP, No. 16-0006 (Tex. Apr. 26, 2019) (emphasis added).

In its introduction to a comprehensive discussion of attorneys’-fee recovery, the Texas Supreme Court said: “It should have been clear from our opinions in [three earlier case] that we intended the lodestar analysis to apply to any situation in which an objective calculation of reasonable hours worked times a reasonable rate can be employed. We reaffirm today that the fact finder’s starting point for calculating an attorney’s fee award is determining the reasonable hours worked multiplied by a reasonable hourly rate, and the fee claimant bears the burden of providing sufficient evidence on both counts.” Rohrmoos Venture v. UTSW DVA Healthcare LLP, No. 16-0006 (Tex. Apr. 26, 2019) (emphasis added).

In a macabre echo of the old English case about the two ships Peerless, in SIG-TX Assets, LLC v. Serrato, Serrato family members accused a funeral home of confusing the bodies of two women named Maria. The funeral home sought to compel arbitration under a theory of direct-benefits estoppel, and the panel majority disagreed: “[A]though SIG-TX’s duty to prepare and inter Maria’s body arose from the contracts, there is an independent duty under Texas tort law to immediate family members not to negligently mishandle a corpse.” A dissent saw the family-members’ claims as directly analogous to those of the nonsignatory to the construction contract in In re: Weekley Homes, 180 S.W.3d 127 (Tex. 2005). No. 05-18-00462-CV (April 23, 2019) (mem. op.) (Partida-Kipness, J., for the majority, joined by Carlyle, J.; Bridges, J., dissenting).

In a macabre echo of the old English case about the two ships Peerless, in SIG-TX Assets, LLC v. Serrato, Serrato family members accused a funeral home of confusing the bodies of two women named Maria. The funeral home sought to compel arbitration under a theory of direct-benefits estoppel, and the panel majority disagreed: “[A]though SIG-TX’s duty to prepare and inter Maria’s body arose from the contracts, there is an independent duty under Texas tort law to immediate family members not to negligently mishandle a corpse.” A dissent saw the family-members’ claims as directly analogous to those of the nonsignatory to the construction contract in In re: Weekley Homes, 180 S.W.3d 127 (Tex. 2005). No. 05-18-00462-CV (April 23, 2019) (mem. op.) (Partida-Kipness, J., for the majority, joined by Carlyle, J.; Bridges, J., dissenting).

A judgment creditor sought mandamus relief, in the trial court, to require the Dallas sheriff to execute necessary title documents after a seizure and forced sale. The Fifth Court (which affirmed the grant of mandamus relief) observed: “An original proceeding for a writ of mandamus initiated in the trial court is a civil action subject to trial and appeal on substantive law issues and the rules of civil procedure as any other lawsuit. This Court has appellate jurisdiction over such proceedings” Gabriel v. Outlaw, No. 05-18-00503-CV (April 22, 2019) (mem. op.)

A judgment creditor sought mandamus relief, in the trial court, to require the Dallas sheriff to execute necessary title documents after a seizure and forced sale. The Fifth Court (which affirmed the grant of mandamus relief) observed: “An original proceeding for a writ of mandamus initiated in the trial court is a civil action subject to trial and appeal on substantive law issues and the rules of civil procedure as any other lawsuit. This Court has appellate jurisdiction over such proceedings” Gabriel v. Outlaw, No. 05-18-00503-CV (April 22, 2019) (mem. op.)

“[I]n concluding the agreed temporary injunction is void and must be dissolved, we necessarily reject Hanson’s contentions that because appellants agreed to the temporary injunction and failed to raise these technical defects in their motion to dissolve, they should be precluded from complaining about the order’s deficiencies under rule 683. We can declare a temporary judgment void even if the parties have not raised the issue. Moreover, because a temporary injunction order that fails to comply with rule 683 is void, a party cannot waive the error by agreeing to the form or substance of the order.” Reiss v. Hanson, No. 05-18-00923-CV (April 22, 2019) (mem op.)

“[I]n concluding the agreed temporary injunction is void and must be dissolved, we necessarily reject Hanson’s contentions that because appellants agreed to the temporary injunction and failed to raise these technical defects in their motion to dissolve, they should be precluded from complaining about the order’s deficiencies under rule 683. We can declare a temporary judgment void even if the parties have not raised the issue. Moreover, because a temporary injunction order that fails to comply with rule 683 is void, a party cannot waive the error by agreeing to the form or substance of the order.” Reiss v. Hanson, No. 05-18-00923-CV (April 22, 2019) (mem op.)

Reiss distinguishes the Fifth Court’s December 2018 opinion about an injunction’s lack of specificity (as opposed to voidness) in In re: Rajpal, which noted: “Relators also claim that the agreed injunction likewise fails for lack of specificity. This argument, however, overlooks that both parties agreed to the entry of this temporary injunction. As a result, Relators are estopped to complain.”

In a recent mandamus opinion, the Fifth Court found that laches began to run when a coordinator’s “e-mail states specifically that the judge had granted the motion to strike and, as such, signing an order was merely a ministerial act.” In re Yamaha Golf-Car Co., 05-19-00292-CV (April 8, 2019) (mem. op.) As a direct-appeal

In a recent mandamus opinion, the Fifth Court found that laches began to run when a coordinator’s “e-mail states specifically that the judge had granted the motion to strike and, as such, signing an order was merely a ministerial act.” In re Yamaha Golf-Car Co., 05-19-00292-CV (April 8, 2019) (mem. op.) As a direct-appeal  counterpoint, Swart v. Morales holds: “Although the record includes a memorandum ruling on the trial court’s letterhead, the ruling is not signed. This Court has jurisdiction over appeals from signed orders or judgments. Without a signed appealable order, this Court lacks jurisdiction over this appeal.” No. 05-18-01229-CV (April 10, 2019) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

counterpoint, Swart v. Morales holds: “Although the record includes a memorandum ruling on the trial court’s letterhead, the ruling is not signed. This Court has jurisdiction over appeals from signed orders or judgments. Without a signed appealable order, this Court lacks jurisdiction over this appeal.” No. 05-18-01229-CV (April 10, 2019) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

“’A mortgagor qualifies as a consumer under the DTPA if his or her primary objective in obtaining the loan was to acquire a good or service, and that good or service forms the basis of the

“’A mortgagor qualifies as a consumer under the DTPA if his or her primary objective in obtaining the loan was to acquire a good or service, and that good or service forms the basis of the

complaint.’ But a mortgagor challenging how an existing mortgage is serviced is not a consumer because the basis of the claim is ‘the subsequent loan servicing and foreclosure activities, rather than the goods or services acquired in the original transaction.’ Also, ‘[a]n activity related to a loan transaction is a ‘service’ for DTPA purposes only if the activity at issue is, from the plaintiff’s point of view, an objective of the transaction, not merely incidental to it.’

Appellant’s DTPA claim is not premised on any deceptive acts regarding the purchase of the property itself. Her claims––e.g., that appellees failed to provide her with an accurate accounting and failed to comply with an alleged oral agreement to delay foreclosure––are based on how the mortgage loan was administered or serviced.” Ebrahimi v. Caliber Home Loans, Inc., No. 05-18-00456-CV (April 15, 2019) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

How long is too long to rule on a pending motion? In In re Hines, it was just under seven months from the first written request for a hearing: “[R]elator’s certified mandamus record includes copies of a motion for judgment nunc pro tunc dated August 24, 2018, and letter requests to the trial court dated September 27, 2018 and November 7, 2018 requesting a hearing on the August 24, 2018 motion for judgment nunc pro

How long is too long to rule on a pending motion? In In re Hines, it was just under seven months from the first written request for a hearing: “[R]elator’s certified mandamus record includes copies of a motion for judgment nunc pro tunc dated August 24, 2018, and letter requests to the trial court dated September 27, 2018 and November 7, 2018 requesting a hearing on the August 24, 2018 motion for judgment nunc pro

tunc. The trial court has had a reasonable time in which to rule on the motion but has taken no action. Under this record, we conclude the trial court has violated its ministerial duty to rule on relator’s motion for judgment nunc pro tunc within a reasonable time.” No. 05-19-00243-CV (April 15, 2019) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

The unfortunately-worded judgment in Last Frontier Realty Corp. v. Budtime Forest Grove Homes, LLC provided:

The unfortunately-worded judgment in Last Frontier Realty Corp. v. Budtime Forest Grove Homes, LLC provided:

. . . this Court finds that the Motion should be, and hereby is GRANTED in all respects.

IT IS THEREFORE ORDERED, ADJUDGED and DECREED that [Last Frontier’s] claims asserted herein are hereby dismissed with prejudice, and all costs of court are taxed against [Last Frontier].

This order disposes of all claims and all parties.

This order is final and unappealable, and all relief not expressly granted herein is denied.

(emphasis added). Sensibly, the Fifth Court held: “[T]he word ‘unappealable’ is a clerical error and [we] reform the trial court’s judgment to replace ‘unappealable’ with ‘appealable.’”

The flip side to the “controlling rule [that] forecloses resort to injunctive relief simply to sequester a source of funds to satisfy a future judgment” is that an “asset freeze” temporary injunction can issue on a proper showing. Here: “Comerica Bank presented evidence that in October 2017, after RWI Construction and RWI

The flip side to the “controlling rule [that] forecloses resort to injunctive relief simply to sequester a source of funds to satisfy a future judgment” is that an “asset freeze” temporary injunction can issue on a proper showing. Here: “Comerica Bank presented evidence that in October 2017, after RWI Construction and RWI

Acquisition defaulted on their loan, RWI Construction collected $800,000 in settlement of a receivable owed by Oxy. Those funds were collateral for the loan at issue in this case. Rather than pay those funds over to Comerica Bank as required upon their receipt, RWI Construction transferred them to Lone Star. Accordingly, the evidence presented by Comerica Bank traced collateral for the loan to Lone Star, and those funds are both logically and justifiably connected to Comerica Bank’s breach of contract claim and the relief it seeks in this case.”

In the same vein, the Court noted that while a showing of insolvency can establish irreparable injury in such a context, it is not always necessary: “To a district court exercising discretion over an injunction decision, unwillingness to pay is just as significant, and perhaps more so, as an inability to pay.” RWI Construction Co v. Comerica Bank, No. 05-18-00265-CV (April 12, 2019).

“[T]he ancient and controlling rule forecloses resort to injunctive relief simply to sequester a source of funds to satisfy a future judgment. That general rule would not control where there is a logical and justifiable connection between the claims alleged and the acts sought to be enjoined, or where the plaintiff claims a specific contractual or equitable interest in the assets it seeks to freeze.” Accordingly, it was an abuse of discretion to enter a temporary injunction (beyond $800,000 as to which such a connection was shown), when “the injunction freezes Lone Star’s funds pretrial simply to assure their future availability to satisfy a judgment based solely on concerns about Lone Star’s general future liquidity.” RWI Construction Co v. Comerica Bank, No. 05-18-00265-CV (April 12, 2019).

“[T]he ancient and controlling rule forecloses resort to injunctive relief simply to sequester a source of funds to satisfy a future judgment. That general rule would not control where there is a logical and justifiable connection between the claims alleged and the acts sought to be enjoined, or where the plaintiff claims a specific contractual or equitable interest in the assets it seeks to freeze.” Accordingly, it was an abuse of discretion to enter a temporary injunction (beyond $800,000 as to which such a connection was shown), when “the injunction freezes Lone Star’s funds pretrial simply to assure their future availability to satisfy a judgment based solely on concerns about Lone Star’s general future liquidity.” RWI Construction Co v. Comerica Bank, No. 05-18-00265-CV (April 12, 2019).

This coming Monday April 15 at the Belo Mansion, the Business Litigation Section presents an excellent panel discussion – “Business Appeals Before the Slate of Eight” – featuring . . . the “Slate of Eight”, the new Democratic judges elected to the Fifth Court last November. Looks like a “don’t miss” presentation.

This coming Monday April 15 at the Belo Mansion, the Business Litigation Section presents an excellent panel discussion – “Business Appeals Before the Slate of Eight” – featuring . . . the “Slate of Eight”, the new Democratic judges elected to the Fifth Court last November. Looks like a “don’t miss” presentation.

In Agar Corp. v. Electro Circuits Int’l LLC, the Texas Supreme Court settled a persistent question about the statute of limitations for civil conspiracy, holding: “Because civil conspiracy is a derivative tort that ‘depends on participation in some underlying tort,’ . . . the applicable statute of limitations must coincide with that of the ‘underlying tort for which the plaintiff seeks to hold at least one of the named defendants liable.'” No. 17-0630 (April 5, 2019).

In Agar Corp. v. Electro Circuits Int’l LLC, the Texas Supreme Court settled a persistent question about the statute of limitations for civil conspiracy, holding: “Because civil conspiracy is a derivative tort that ‘depends on participation in some underlying tort,’ . . . the applicable statute of limitations must coincide with that of the ‘underlying tort for which the plaintiff seeks to hold at least one of the named defendants liable.'” No. 17-0630 (April 5, 2019).

The opinion does not appear to directly address two other recurring questions about civil conspiracy law in Texas today; namely, (1) the interaction between civil conspiracy and the Texas comparative-fault statute, and (2) whether a proper jury charge on civil conspiracy requires an instruction (or finding )about injury flowing from the conspiracy itself, as opposed to the damages attributable to the underlying tort. However, the Court’s thorough review of conspiracy law may offer indirect insight about those issues with further review.

In a serious personal injury case, the trial court denied the defendant’s designation of a responsible third party, and the Fifth Court denied mandamus relief for two reasons of substantial general interest:

In a serious personal injury case, the trial court denied the defendant’s designation of a responsible third party, and the Fifth Court denied mandamus relief for two reasons of substantial general interest:

- No mandamus relief for an unsettled issue of first impression. The controlling question of law (what legal framework governs the designation of an emergency-care provider as a responsible third party) presented an issue of first impression. The Court noted that “[a]n issue of first impression can qualify for mandamus relief even though the factual scenario has never been precisely addressed when the principle of law has been clearly established,” but concluded: “Mandamus is unwarranted here because the principle of law Yamaha urged the trial court to follow is neither positively commanded nor plainly prescribed under the law.” (Fans of this blog will note that I identified this issue last year as a topic where the “Slate of Eight” could begin to narrow mandamus review.)

- Laches from an email announcement of a ruling. The Court found that laches barred mandamus relief, reasoning: “Yamaha waited eight months after the trial court’s July 12, 2018 e-mail ruling to seek mandamus relief, filed the petition only three weeks before trial, and initially offered no explanation for the delay. In its reply brief, Yamaha argues that the e-mail from the court coordinator was not sufficiently clear and specific to be reviewed by mandamus but was, instead, simply an expression of future intent to sign a written order. We disagree. The e-mail states specifically that the judge had granted the motion to strike and, as such, signing an order was merely a ministerial act.” (citations omitted). (For reference here is the first page of the email in question.)

In re Yamaha Golf-Car Co., 05-19-00292-CV (April 8, 2019) (mem. op.)

Footnote 11 of the Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in West v. Quintanilla clarified the two distinct doctrines, each of which is commonly referred to as “the parol evidence rule”: “The contract-construction rule applies when a contract is written and unambiguous, and it prohibits consideration of oral or extrinsic evidence to modify or add to the contract’s terms. ‘[T]he construction of an unambiguous contract, including the determination of whether it is unambiguous, depends on the language of the contract itself, construed in light of the surrounding circumstances.’ By contrast, the parol evidence rule applies when a contract is written and integrated, and it precludes enforcement of any prior or contemporaneous agreement that is inconsistent with the written contract’s terms.” No. 17-0454 (Tex. Apr. 5, 2019) (citations omitted).

Footnote 11 of the Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in West v. Quintanilla clarified the two distinct doctrines, each of which is commonly referred to as “the parol evidence rule”: “The contract-construction rule applies when a contract is written and unambiguous, and it prohibits consideration of oral or extrinsic evidence to modify or add to the contract’s terms. ‘[T]he construction of an unambiguous contract, including the determination of whether it is unambiguous, depends on the language of the contract itself, construed in light of the surrounding circumstances.’ By contrast, the parol evidence rule applies when a contract is written and integrated, and it precludes enforcement of any prior or contemporaneous agreement that is inconsistent with the written contract’s terms.” No. 17-0454 (Tex. Apr. 5, 2019) (citations omitted).

Silverado’s answer was stricken because, as an LLC, it could not proceed pro se. A default judgment resulted and Silverado affirmed. Among other holdings, as to Silverado’s challenges to the damages evidence, the Fifth Court held: “An objection that an affidavit in support of a motion

Silverado’s answer was stricken because, as an LLC, it could not proceed pro se. A default judgment resulted and Silverado affirmed. Among other holdings, as to Silverado’s challenges to the damages evidence, the Fifth Court held: “An objection that an affidavit in support of a motion  for summary judgment contains hearsay is an objection to the form of the affidavit. To preserve this complaint for appellate review, Silverado was required to make the objection in the trial court and obtain a ruling from the trial judge. Because it did not retain counsel or otherwise appear as ordered, Silverado obviously did not make a hearsay objection in the trial court and, therefore, has waived its complaint on appeal.” Silverado Truck & Diesel Repair LLC v. Lawson, No. 05-18-00540-CV (April 3, 2019) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

for summary judgment contains hearsay is an objection to the form of the affidavit. To preserve this complaint for appellate review, Silverado was required to make the objection in the trial court and obtain a ruling from the trial judge. Because it did not retain counsel or otherwise appear as ordered, Silverado obviously did not make a hearsay objection in the trial court and, therefore, has waived its complaint on appeal.” Silverado Truck & Diesel Repair LLC v. Lawson, No. 05-18-00540-CV (April 3, 2019) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

“Appellate timetables do not run from the date the non-suit is filed, but from the date the trial court signs the order of dismissal.” Kerville Fitness Property LLC v. PE Services LLC, No. 05-17-01317-CV (March 25, 2019) (mem. op.) (citing In re: Bennett, 960 S.W.2d 35 (Tex. 1997)). Accordingly, a partial summary judgment order, coupled with a nonsuit of other claims, does not create finality for purposes of appellate deadlines.

“Appellate timetables do not run from the date the non-suit is filed, but from the date the trial court signs the order of dismissal.” Kerville Fitness Property LLC v. PE Services LLC, No. 05-17-01317-CV (March 25, 2019) (mem. op.) (citing In re: Bennett, 960 S.W.2d 35 (Tex. 1997)). Accordingly, a partial summary judgment order, coupled with a nonsuit of other claims, does not create finality for purposes of appellate deadlines.

Mauldin v. Redington  was a residential lease dispute about an elegant property on Dallas’s Swiss Avenue (right). A key issue was agency, and the Fifth Court found it was not proven:

was a residential lease dispute about an elegant property on Dallas’s Swiss Avenue (right). A key issue was agency, and the Fifth Court found it was not proven:

‘Mauldin contends there is no evidence of Holt’s actual authority to sign his name to the agreement, and we agree. The evidence shows Mauldin helped Holt with expenses, and Holt told Mauldin she “thought that it would require his participation” for her “to get the lease” and she “thought he said, yes.” But, the only evidence regarding Holt’s authority to sign Mauldin’s name to the agreement was her understanding that he agreed to let her “use his information to pay [her] lease” and, from that, she inferred she was allowed to sign his name. Even then, Holt acknowledged it was possible Mauldin did not understand what she was asking of him. We conclude Holt’s vague deposition testimony is no more than a scintilla of evidence that the scope of her actual authority, if any, extended to legally binding Mauldin to the agreement by signing his name.

. . .

Moreover, an alleged agent’s declarations alone are incompetent evidence to establish the existence or scope of an alleged agency.’

No. 05-18-00401-CV (March 29, 2019).

The jury in Aztec Systems, Inc. v. glendonTodd Capital, LLC found a “joint enterprise” among the defendants in a contract dispute and the Fifth Court reversed. Assuming without deciding that the doctrine applied outside the tort context, the Court found that no evidence showed “how, or whether, the monetary benefits of the enterprise were shared,” or that the two businesses had “an equal right to a voice in the direction of the enterprise.” Potential profit from an eventual sale of one of the businesses was “insufficient to establish a community of pecuniary interest.” No. 05-18-00183-CV (March 29, 2019) (mem. op.) (applying, inter alia, David L. Smith & Assocs.. LLP v. Stealth Detection, Inc., 327 S.W.3d 873 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2010, no pet.)

The jury in Aztec Systems, Inc. v. glendonTodd Capital, LLC found a “joint enterprise” among the defendants in a contract dispute and the Fifth Court reversed. Assuming without deciding that the doctrine applied outside the tort context, the Court found that no evidence showed “how, or whether, the monetary benefits of the enterprise were shared,” or that the two businesses had “an equal right to a voice in the direction of the enterprise.” Potential profit from an eventual sale of one of the businesses was “insufficient to establish a community of pecuniary interest.” No. 05-18-00183-CV (March 29, 2019) (mem. op.) (applying, inter alia, David L. Smith & Assocs.. LLP v. Stealth Detection, Inc., 327 S.W.3d 873 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2010, no pet.)