The How ards argued that their note was not a negotiable instrument (and thus, not subject to a 6-year statute of limitations), citing provisions in the note about late fees, notice obligations, and a usury savings clause. While under the UCC, an instrument can become non-negotiatble if it includes “any other undertaking or instruction by the person promising or ordering payment to do any act in addition to the payment of money,” these provisions were permissible as “an undertaking or power to give, maintain, or protect collateral to secure payment.” PNC v. Howard, No. 05-17-01484-CV (June 24, 2019) (applying TBOC § 3.104(a)).

ards argued that their note was not a negotiable instrument (and thus, not subject to a 6-year statute of limitations), citing provisions in the note about late fees, notice obligations, and a usury savings clause. While under the UCC, an instrument can become non-negotiatble if it includes “any other undertaking or instruction by the person promising or ordering payment to do any act in addition to the payment of money,” these provisions were permissible as “an undertaking or power to give, maintain, or protect collateral to secure payment.” PNC v. Howard, No. 05-17-01484-CV (June 24, 2019) (applying TBOC § 3.104(a)).

Monthly Archives: June 2019

Conditionally granting mandamus relief from this order by the Fifth Court (a “lift-stay” order in a TCPA appeal), in In re Geomet Recycling, the Texas Supreme Court held:

Conditionally granting mandamus relief from this order by the Fifth Court (a “lift-stay” order in a TCPA appeal), in In re Geomet Recycling, the Texas Supreme Court held:

“[T]o the extent EMR faced irreparable harm, it had an avenue available to it by which a court could provide a remedy without violating the statutory stay. It did not pursue that remedy but instead asked the court of appeals to lift the stay in violation of [CPRC] section 51.014(b). EMR’s choice of an unsuited procedural mechanism does not create a constitutional problem we must address. And to the extent EMR did not face irreparable harm but simply wanted a hearing on the trial-court motions that had been pending when Geomet’s appeal triggered the stay, that is exactly what [CPRC] section 51.014(b) prohibits.”

It also observed: “Whether . . . an order under [TRAP] 29.3 referring a motion to the trial court for findings and recommendations would violate the statutory stay ‘of all trial court proceedings’ is a question the parties have not briefed and that we need not decide.” No. 18-0443 (June 14, 2019).

In Lei v. Natural Polymer Int’l Corp., the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a TCPA motion (and then some) in a trade-secrets dispute about the making of “natural pet treats,” holding:

- Association. Under Dyer v. Medoc Health Services, while another appeal district might have a different view, under Dallas precedent the plaintiff failed to invoke the TCPA’s protection of assocation rights;

- Speech. “We cannot conclude that these alleged ‘communications’ are tangentially related to a matter of public concern simply because the proprietary and confidential information at issue belonged to a company in the business of selling pet treats that promote health ‘or because the alleged tortfeasors hoped to profit from their conduct.’”’

- Petition. [T]o construe the TCPA such that appellants exercised a ‘right to petition’ based on their deposition testimony . . . ‘is an absurd result that would not further the purpose of the TCPA to curb strategic lawsuits against public participation.’” (applying Miller Weisbrod, LLP v. Llamas-Soforo, 511 S.W.3d 181, 192–93 (Tex. App.—El Paso 2014, no pet.); and

- Award of fees. It was not an abuse of discretion to find the TCPA motion frivolous, when at an earlier temporary-injunction hearing, “[t]he trial court had already heard evidence supporting NPIC’s pleaded causes of action at the time appellants filed their motion to dismiss.”

No. 05-18-01041-CV (June 21, 2019).

Here is my PowerPoint from the recent appellate course sponsored by University of Texas CLE. I also discussed this month’s opinion in In re: City of Houston, granting mandamus relief in a privilege dispute.

Here is my PowerPoint from the recent appellate course sponsored by University of Texas CLE. I also discussed this month’s opinion in In re: City of Houston, granting mandamus relief in a privilege dispute.

Valor Energy sued Price Drilling in Dallas County; Price sought transfer to Starr County, where the relevant oil well was located, and the Fifth Court denied Price’s mandamus petition, which was based on the mandatory-venue provision about the location of real estate (CPRC § 15.011). The Court reasoned: “The record shows that the contract was executed in Dallas County, the alleged negligence is based on Price’s performance of its drilling obligations, and the fraud claims relate in part to some actions directed at Valor in Dallas County. Valor does not seek damages for oil that has been wrongfully removed from its property, and does not seek any declarations as to Valor’s or Price’s rights to any portions of the property itself. Rather, Valor seeks breach of contract, fraud, and negligence damages for Price’s failure to fulfill its duties under the contract to re-drill the Well and for the misrepresentations made by Price to Valor regarding Price’s work on the alleged compliance with the terms of the contract.” In re Price Drilling Rig No. 5 Co., No. 05-19-00344-CV (June 17, 2019) (mem. op.)

Valor Energy sued Price Drilling in Dallas County; Price sought transfer to Starr County, where the relevant oil well was located, and the Fifth Court denied Price’s mandamus petition, which was based on the mandatory-venue provision about the location of real estate (CPRC § 15.011). The Court reasoned: “The record shows that the contract was executed in Dallas County, the alleged negligence is based on Price’s performance of its drilling obligations, and the fraud claims relate in part to some actions directed at Valor in Dallas County. Valor does not seek damages for oil that has been wrongfully removed from its property, and does not seek any declarations as to Valor’s or Price’s rights to any portions of the property itself. Rather, Valor seeks breach of contract, fraud, and negligence damages for Price’s failure to fulfill its duties under the contract to re-drill the Well and for the misrepresentations made by Price to Valor regarding Price’s work on the alleged compliance with the terms of the contract.” In re Price Drilling Rig No. 5 Co., No. 05-19-00344-CV (June 17, 2019) (mem. op.)

“[Appellant]’s motion asserted that [he] was ‘unsophisticated in legal matters’ and did not understand he was required to file an answer and thought he would receive a hearing notice before any judgment was rendered. Not understanding a citation and then doing nothing after being served does not constitute a mistake of law that is sufficient to meet the first Craddock element.” Chapple v. Hall, No. 05-18-01209-CV (June 14, 2019) (mem. op.)

“[Appellant]’s motion asserted that [he] was ‘unsophisticated in legal matters’ and did not understand he was required to file an answer and thought he would receive a hearing notice before any judgment was rendered. Not understanding a citation and then doing nothing after being served does not constitute a mistake of law that is sufficient to meet the first Craddock element.” Chapple v. Hall, No. 05-18-01209-CV (June 14, 2019) (mem. op.)

Not offered in evidence? Might not be a problem, at least on the following record::

Not offered in evidence? Might not be a problem, at least on the following record::

On appeal, the Pelley parties argue that the evidence is legally insufficient to support the award because there was no sworn expert witness testimony, neither of the “two exhibits which the attorney for the Wynne Parties handed to the court reporter to be marked . . . were ever offered into evidence by the [Wynne parties], nor were they ever admitted into evidence by a ruling of the Trial Court.” They also contend that even if the statements by the Wynne parties’ counsel had been properly presented to the trial court, his assertions “would have been objected to as being unreliable, and should have been excluded as evidence.” [1] The Pelley parties, however, did not object to, but rather discussed, the Westfall affidavit in their arguments in the trial court. [2] Nor did the Pelley parties object to the Wynne parties’ references to Westfall’s billing records on the basis they were not in evidence. The reporter’s record clearly shows that the parties and the trial court treated the Westfall affidavit and attached billing records as if they had been admitted into evidence. We conclude that the Westfall affidavit and attached billing records were, “for all practical purposes, admitted.”

Pelley v. Wynne, No. 05-18-00550-CV (June 13, 2019) (emphasis and colorful highlighting added).

A dispute about the operation of the mandate rule, in a long-running dispute about the winding up of a law partnership, unfolded as follows:

A dispute about the operation of the mandate rule, in a long-running dispute about the winding up of a law partnership, unfolded as follows:

- Trial court, first time. The trial court’s first judgment, in a dispute about the winding-up of a law partnership, “[a]mong other things, . . . ordered Pelley and Scott Pelley P.C. to pay $55,672.80 to Wynne and Smith as reimbursement for overhead operation expenses incurred as part of the law firm’s post-dissolution expenses during the years ‘2012 to present’ and ordered the Pelley parties to pay $40,000 to the Wynne parties for attorney’s fees incurred ‘in connection with the Gibbs Estate and Shankles Estate cases.'” (emphasis added, here and below)

- Court of appeals, first time. On appeal from that judgment, the Fifth Court held, in part: “[T]he trial court erred when it failed to include contingent attorney’s fees on appeal in the final judgment.

The trial court’s final judgment is reversed as to Wynne’s and Smith’s request for contingent appellate attorneys’ fees and remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion. The remainder of the trial court’s judgment is affirmed.” - Trial court, second time. On remand, the trial court awarded additional, post-judgment overhead expenses, to which the losing party objected: “[T]he final judgment ordered the paying of overhead through the date of the trial. There is no provision in the final judgment or anywhere else where this Court ordered any sort of continuing obligation after the date of judgment. Frankly, if it did, it wouldn’t be a final judgment. There simply is no provision in the final judgment for the amount that counsel is proposing for additional overhead.”

- Court of appeals, second time. “We agree . . . .on remand the trial court had no authority to address the matter of overhead expenses, which had been finally adjudicated by our first opinion, judgment, and mandate. We remanded this case with specific instructions [about attorneys’ fees].”

Pelley v. Wynne, No. 05-18-00550-CV (June 13, 2019).

Here is a copy of my PowerPoint from today. Thanks to all who came out, and to the DBA Appellate Section for the invitation!

Here is a copy of my PowerPoint from today. Thanks to all who came out, and to the DBA Appellate Section for the invitation!

On Thursday June 13 at noon, I will speak to the DBA Appellate Law Section (and anyone else within earshot) to give an update on business law cases from the Dallas Court of Appeals in 2019. This should be a fun opportunity to look at the impact of the Slate of Eight since taking office at the start of the year. I will post the PowerPoint after the event (since it will not be done until then!)

On Thursday June 13 at noon, I will speak to the DBA Appellate Law Section (and anyone else within earshot) to give an update on business law cases from the Dallas Court of Appeals in 2019. This should be a fun opportunity to look at the impact of the Slate of Eight since taking office at the start of the year. I will post the PowerPoint after the event (since it will not be done until then!)

600Commerce’s sister blog once described a federal appeal that became moot when, literally, the ship had sailed; a similar principle applies in a dispute about the right of possession (in Texas practice, a forcible detainer action), which becomes moot when “a writ of possession had been served on appellant” and thus “appellant is no longer in possession of [the] premises.” Jones v. Willems, No. 05-18-01191-CV (June 7, 2019). (The ship in question, since reflagged as the M/V CALHOUN, is in Singapore as of the date of this post, still well away from Fifth Circuit jurisdiction).

600Commerce’s sister blog once described a federal appeal that became moot when, literally, the ship had sailed; a similar principle applies in a dispute about the right of possession (in Texas practice, a forcible detainer action), which becomes moot when “a writ of possession had been served on appellant” and thus “appellant is no longer in possession of [the] premises.” Jones v. Willems, No. 05-18-01191-CV (June 7, 2019). (The ship in question, since reflagged as the M/V CALHOUN, is in Singapore as of the date of this post, still well away from Fifth Circuit jurisdiction).

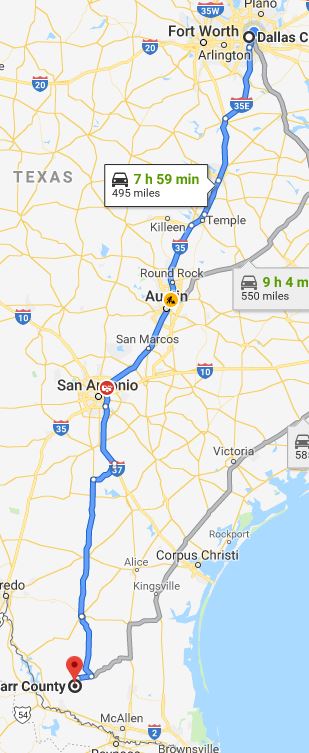

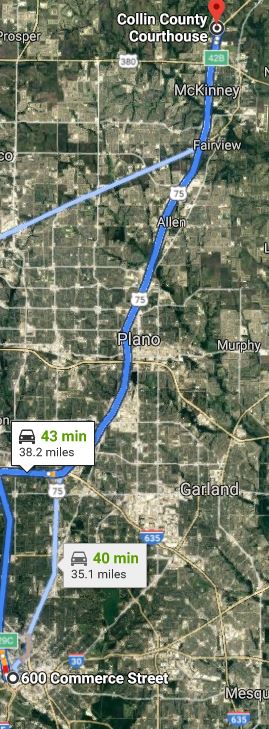

The 35-mile distance between the Collin and Dallas County courthouses (right) was dispositive in Condie v. McLaughlin, which presented this venue error:

The 35-mile distance between the Collin and Dallas County courthouses (right) was dispositive in Condie v. McLaughlin, which presented this venue error:

- McLaughlin sued Condie for breach of contract in Dallas, and won summary judgment in January 2016.

- Later that year, Condie’s P.C. sued McLaughlin for breach of (the same) contract in Collin County.

- McLaughlin sought transfer to Dallas, arguing that venue there was mandatory under CPRC § 15.062, because the PC’s claim was a “compulsory third-party claim that should have been brought” in the original Dallas suit.

- The trial court agreed and transferred (noting that it was not relying on the “convenience” provisions of CPRC § 15.002(b)).

The Fifth Court reversed – and with that reversal, vacated a favorable summary judgment that McLaughlin had gone on to win in Dallas – because “the record reflects no attempt, proper or otherwise, by Condie to join [the PC] in McLaughlin’s original suit against her” as required by § 15.062. No. 05-18-00085-CV (June 3, 2019) (mem. op.)

The recent Texas Supreme Court case of Pathfinder Oil & Gas v. Great Western Drilling reminds: “Parties can . . . waive their right to proof of a fact or an element of a claim through a written stipulation or one made in open court.” No. 18-0186 (Tex. May 24, 2019). Such agreements, commonly called “Rule 11 Agreements” in Texas practice for the relevant state rule of civil procedure, are “contracts relating to litigation” and are “construe[d] . . . under the same rules as a contract.” The more challenging question about a challenge to formation of such an agreement, rather than its interpretation, is the subject of a recent article that I co-authored in a State Bar Litigation Section publication.

The recent Texas Supreme Court case of Pathfinder Oil & Gas v. Great Western Drilling reminds: “Parties can . . . waive their right to proof of a fact or an element of a claim through a written stipulation or one made in open court.” No. 18-0186 (Tex. May 24, 2019). Such agreements, commonly called “Rule 11 Agreements” in Texas practice for the relevant state rule of civil procedure, are “contracts relating to litigation” and are “construe[d] . . . under the same rules as a contract.” The more challenging question about a challenge to formation of such an agreement, rather than its interpretation, is the subject of a recent article that I co-authored in a State Bar Litigation Section publication.

BCH Development sought to build a two-story house; the neighborhood association sued to enforce a restrictive covenant limiting construction to a “single family dwelling not to exceed one story in height.” Because a two-story house stood on the neighboring lot, BCH argued waiver; the association countered that 1 nonconforming lot out of 104 could not establish waiver. The Fifth Court remanded for trial on the issue of waiver, noting: “Waiver in restrictive covenant cases is a fact-intensive inquiry involving multiple factors. A statistical analysis is but one component in determining the issue of waiver. Also relevant are the nature and severity of existing violations, any prior acts of enforcement of the restriction, and whether it is still possible to realize to a substantial degree the benefits intended through the covenant.” BCH Development v. Lakeview Heights Addition Property Owners’ Assoc., No. 05-17-01096-CV (March 21, 2019). Notably, the opinion was decided by a 2-judge panel of Justices Myers and Brown, after Justice Evans was not re-elected in 2018.

BCH Development sought to build a two-story house; the neighborhood association sued to enforce a restrictive covenant limiting construction to a “single family dwelling not to exceed one story in height.” Because a two-story house stood on the neighboring lot, BCH argued waiver; the association countered that 1 nonconforming lot out of 104 could not establish waiver. The Fifth Court remanded for trial on the issue of waiver, noting: “Waiver in restrictive covenant cases is a fact-intensive inquiry involving multiple factors. A statistical analysis is but one component in determining the issue of waiver. Also relevant are the nature and severity of existing violations, any prior acts of enforcement of the restriction, and whether it is still possible to realize to a substantial degree the benefits intended through the covenant.” BCH Development v. Lakeview Heights Addition Property Owners’ Assoc., No. 05-17-01096-CV (March 21, 2019). Notably, the opinion was decided by a 2-judge panel of Justices Myers and Brown, after Justice Evans was not re-elected in 2018.