Monthly Archives: August 2019

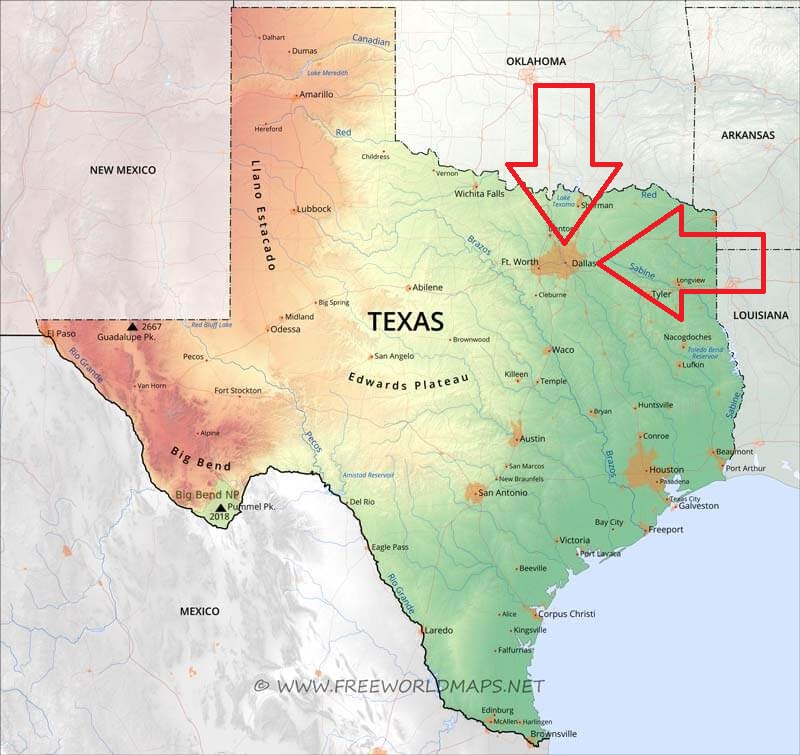

Dallas-Fort Worth is the fourth largest metropolitan area in the United States, and it is only a matter of time until it passes Chicago to become #3. Dallas is routinely ranked among the nation’s best cities. Yet, as noted in a recent Texas Lawbook op-ed, it is significantly underrepresented on the Texas Supreme Court. Hopefully, geographic diversity will play a role in future appointments to that Court.

Dallas-Fort Worth is the fourth largest metropolitan area in the United States, and it is only a matter of time until it passes Chicago to become #3. Dallas is routinely ranked among the nation’s best cities. Yet, as noted in a recent Texas Lawbook op-ed, it is significantly underrepresented on the Texas Supreme Court. Hopefully, geographic diversity will play a role in future appointments to that Court.

Denny successfully sued Chang for medical malpractice, based on a cotton ball left inside her head after brain surgery. The key appellate issue was a jury question about Denny’s “degree of diligence” in bringing suit – a finding needed to support her open courts counter-defense to the two-year statute of limitations on her claim. The majority opinion first found waiver about an objection to the form of the question, and then found that sufficient evidence supported the jury’s finding, noting testimony about her difficulty in finding a treating physician who did not “fear[] they were going to be dragged into litigation,” and that her health problems precluded her from meeting with counsel for substantial periods of time. Chang v. Denny, No. 05-17-01457-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.).

Denny successfully sued Chang for medical malpractice, based on a cotton ball left inside her head after brain surgery. The key appellate issue was a jury question about Denny’s “degree of diligence” in bringing suit – a finding needed to support her open courts counter-defense to the two-year statute of limitations on her claim. The majority opinion first found waiver about an objection to the form of the question, and then found that sufficient evidence supported the jury’s finding, noting testimony about her difficulty in finding a treating physician who did not “fear[] they were going to be dragged into litigation,” and that her health problems precluded her from meeting with counsel for substantial periods of time. Chang v. Denny, No. 05-17-01457-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.).

A dissent criticized the treatment of this issue as one of fact, warning of it “disappearing into the amorphous slurry of jury deliberations,” and that “the misunderstandings and inaction of her legal counsel” were to blame for the delay. Underlying the dissent was concern as to “why the Legislature has remained silent for the past 18 years” since the Texas Supreme Court first connected Texas’s open-courts guarantee to an inherently undiscoverable medical injury in Shah v. Moss, 67 S.W.3d 836 (Tex. 2001).

CExchange sold several thousand used headphones and speakers to Top Wireless. Top Wireless complained about the quality of the goods; CE Exchange defended by reference to an “as is” clause in their contract documents. The Fifth Court found that the clause did not preclude Top Wireless’s claims and affirmed a jury verdict in its favor, noting:

CExchange sold several thousand used headphones and speakers to Top Wireless. Top Wireless complained about the quality of the goods; CE Exchange defended by reference to an “as is” clause in their contract documents. The Fifth Court found that the clause did not preclude Top Wireless’s claims and affirmed a jury verdict in its favor, noting:

- The jury’s finding on a contract-formation question “amounts to a determination that the ‘as is’ clause was not an operative part of the subject agreement”; and

- Alternatively, other jury findings established the fraudulent-inducement exception to the enforceability of such a clause, citing Prudential Ins. v. Jefferson Assocs., 896 S.W.2d 156 (Tex. 1995).

CExchange, LLC v. Top Wireless Wholesaler, No. 05-17-01318-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.).

The panel in CKJ Trucking v. City of Honey Grove found a waiver of sovereign immunity in an unusual fact situation involving an off-duty police officer. The Fifth Court considered whether to take the matter en banc, and it appears to have fallen short by one vote. the Court’s five Republicans joined a dissent by Justice Reichek; three of whom dissented yet more in an additional opinion. No. 05-18-00205-CV (July 23, 2019 (panel), August 22, 2019 (en banc opinions).

The panel in CKJ Trucking v. City of Honey Grove found a waiver of sovereign immunity in an unusual fact situation involving an off-duty police officer. The Fifth Court considered whether to take the matter en banc, and it appears to have fallen short by one vote. the Court’s five Republicans joined a dissent by Justice Reichek; three of whom dissented yet more in an additional opinion. No. 05-18-00205-CV (July 23, 2019 (panel), August 22, 2019 (en banc opinions).

This footnote:

when not responded to in the trial court, was a sufficient basis for affirmance of a no-evidence summary judgment on appeal as to the “confidentiality agreement” referenced in the footnote. Prophet Equity LP v. Twin City Fire Ins. Co., No. 05-17-00927-CV (Aug. 19, 2019) (mem. op.).

Section 21.563(c)(1) of the Business Organizations Code says: “If justice requires . . . a derivative proceeding brought by a shareholder of a closely held corporation may be treated by a court as a direct action brought by the shareholder for the shareholder’s own benefit.” Cooke v. Karlseng reminds that this statute serves a specific purpose–a reminder with important consequences for standing and limitations issues: “Section 21.563 does not turn a derivative claim into an individual claim. This Court has concluded that although the statute permits a court to ‘treat a derivative action as a direct action by a shareholder, the claims remain vested in the corporation.’ Rather than transforming the nature of the plaintiff’s claim, the statute permits the trial court to award damages in a derivative proceeding directly to the shareholder ‘if necessary to protect the interests of creditors or other shareholders of the corporation.'” No. 05-18-00206-CV (Aug. 14, 2019) (mem. op.).

Section 21.563(c)(1) of the Business Organizations Code says: “If justice requires . . . a derivative proceeding brought by a shareholder of a closely held corporation may be treated by a court as a direct action brought by the shareholder for the shareholder’s own benefit.” Cooke v. Karlseng reminds that this statute serves a specific purpose–a reminder with important consequences for standing and limitations issues: “Section 21.563 does not turn a derivative claim into an individual claim. This Court has concluded that although the statute permits a court to ‘treat a derivative action as a direct action by a shareholder, the claims remain vested in the corporation.’ Rather than transforming the nature of the plaintiff’s claim, the statute permits the trial court to award damages in a derivative proceeding directly to the shareholder ‘if necessary to protect the interests of creditors or other shareholders of the corporation.'” No. 05-18-00206-CV (Aug. 14, 2019) (mem. op.).

The plaintiff in Global Supply Chain Solutions LLC v. Riverwood Solutions, Inc, a trade-secrets dispute, argued “the inevitable disclosure doctrine applies to provide evidence raising a fact issue on damages.” The Fifth Court observed that Texas has adopted the Unitorm Trade Secrets Act, which allows injunctive relief in connection with “threatened misappropriation” of trade secrets. But under Fifth Court precedent, temporary-injunction proceedings about trade secrets do not put the “ultimate merits” at issue; accordingly, “a threatened misappropriation for purposes of a temporary injunction is not a substitute for evidence of the ‘actual loss caused by misappropriation and the unjust enrichment caused by misappropriation that is not taken into account in computing actual loss’ to raise a fact issue on damages in response to a motion for summary judgment.” No. 05-18-00188-CV (Aug. 16, 2019) (mem. op.)

The plaintiff in Global Supply Chain Solutions LLC v. Riverwood Solutions, Inc, a trade-secrets dispute, argued “the inevitable disclosure doctrine applies to provide evidence raising a fact issue on damages.” The Fifth Court observed that Texas has adopted the Unitorm Trade Secrets Act, which allows injunctive relief in connection with “threatened misappropriation” of trade secrets. But under Fifth Court precedent, temporary-injunction proceedings about trade secrets do not put the “ultimate merits” at issue; accordingly, “a threatened misappropriation for purposes of a temporary injunction is not a substitute for evidence of the ‘actual loss caused by misappropriation and the unjust enrichment caused by misappropriation that is not taken into account in computing actual loss’ to raise a fact issue on damages in response to a motion for summary judgment.” No. 05-18-00188-CV (Aug. 16, 2019) (mem. op.)

Tex. R. App. 49.7 says: “A party may file a motion for en banc reconsideration as a separate motion, with or without filing a motion for rehearing. The motion must be filed within 15 days after the court of appeals’ judgment or order, or when permitted, within 15 days after the court of appeals’ denial of the party’s last timely filed motion for rehearing or en banc reconsideration. . . . ”

Tex. R. App. 49.7 says: “A party may file a motion for en banc reconsideration as a separate motion, with or without filing a motion for rehearing. The motion must be filed within 15 days after the court of appeals’ judgment or order, or when permitted, within 15 days after the court of appeals’ denial of the party’s last timely filed motion for rehearing or en banc reconsideration. . . . ”

An en banc majority of the Fifth Court concluded that this rule allowed the filing of a petition for en banc reconsideration within 15 days of an order denying panel rehearing. A concurrence reached the same result for a different reason, “informed by a mandate from the supreme court that requires us to examine a case on its merits when there is an ‘arguable interpretation’ that would allow us to do so.” (Its author, Justice Schenck, followed similar principles in his dissent last year from St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church v. Flakes.) And a dissent approached the rules differently, finding that they “treat panel rehearing and en banc reconsideration motions equally in this regard and give a party only one guaranteed opportunity to file either or both of those motions unless we change our judgment or opinion.” Cruz v. Ghani, No. 05-17-00566-CV (July 22, 2019) (en banc).

Majority: “Gutman’s petition alleges that Wells requested a release, Gutman refused to provide the release, and Wells and Arbitrage harassed and threatened Gutman because he refused to provide the release. This sets out a controversy—whether Gutman must provide the requested release—that is real and not hypothetical. Taking all reasonable inferences in Gutman’s favor there is a justiciable controversy because Wells is repeatedly harassing and threatening Gutman. Although these allegations are less than specific, at this early [Rule 91a] stage they adequately assert that the declaratory judgment will serve a useful purpose of terminating the parties’ controversy and ending the harassment and threats.”

“Gutman’s petition alleges that Wells requested a release, Gutman refused to provide the release, and Wells and Arbitrage harassed and threatened Gutman because he refused to provide the release. This sets out a controversy—whether Gutman must provide the requested release—that is real and not hypothetical. Taking all reasonable inferences in Gutman’s favor there is a justiciable controversy because Wells is repeatedly harassing and threatening Gutman. Although these allegations are less than specific, at this early [Rule 91a] stage they adequately assert that the declaratory judgment will serve a useful purpose of terminating the parties’ controversy and ending the harassment and threats.”

Dissent: “First, Gutman does not seek construction of a contract, nor does he argue that his rights have been ‘affected by a statute, municipal ordinance, contract, or franchise . . . .’ Second, a fair reading of Gutman’s petition, and the majority’s characterization of it, shows his claims for civil harassment, to the extent such a cause of action exists, sound in tort.”

Gutman v. Wells, No. 05-18-01227-CV (Aug. 5, 2019) (mem. op.), and dissent.

Ward sued Gray, alleging that “Gray forced Ward’s resignation to preclude the Partnership’s obligation to purchase Ward’s [partnership] interest. . . . In addition, Ward alleges that [the general partner] made defamatory statements about his employment status when Partnership employees were told that Ward resigned.”

Ward sued Gray, alleging that “Gray forced Ward’s resignation to preclude the Partnership’s obligation to purchase Ward’s [partnership] interest. . . . In addition, Ward alleges that [the general partner] made defamatory statements about his employment status when Partnership employees were told that Ward resigned.”

The relevant limited-partnership agreement, signed by both Gray and Ward, said: “All disputes and claims relating to this Agreement, the rights and obligations of the parties hereto, or any claims or causes of action relating to the performance of either party that have not been settled through mediation will be settled by arbitration.”

The Gray v. Ward majority found that all of Ward’s claims were subject to arbitration: “As Ward’s petition demonstrates, the factual allegations supporting his contract and fiduciary duty breach claims are intertwined with the LP Agreement and Ward’s wrongful termination and defamation claims. Indeed, the only way the statement about Ward’s resignation could be defamatory is in the context of the limited partnership’s operation. The LP Agreement controls the terms of the buy-out from which the entire dispute arises. Under these circumstances, we cannot conclude that Ward’s wrongful termination and defamation claims are completely independent of and can be maintained without reference to the LP Agreement.”

A dissent reasoned: “Ward’s employment-related claims have no significant relationship to the limited partnership agreement, and . . . the arbitration agreement here applies only to Ward’s role as a limited partner . . . , and not to his distinct role as an employee,” and concluded: “This is yet another case in which arbitration becomes a matter of coercion, not consent, with the right to trial by jury as the recurrent fatality.”

A dissent reasoned: “Ward’s employment-related claims have no significant relationship to the limited partnership agreement, and . . . the arbitration agreement here applies only to Ward’s role as a limited partner . . . , and not to his distinct role as an employee,” and concluded: “This is yet another case in which arbitration becomes a matter of coercion, not consent, with the right to trial by jury as the recurrent fatality.”

No. 05-18-00266-CV (Aug. 9, 2019).

- I have an Op-Ed piece in today’s Dallas Morning News about interesting recent dissents in the Dallas Court of Appeals.

- And, I have a recent Texas Lawbook article about the en banc opinions in McPherson v. Rudman.

A slight variation in the Fifth Court’s standard summary of the mandamus standard appeared in In re Oncor: “Entitlement to mandamus relief requires relator to show that the trial court abused its discretion, which may occur if the trial

A slight variation in the Fifth Court’s standard summary of the mandamus standard appeared in In re Oncor: “Entitlement to mandamus relief requires relator to show that the trial court abused its discretion, which may occur if the trial  court fails to correctly analyze or apply the law, In re Sw. Bell Tel. Co., L.P., 226 S.W.3d 400, 403 (Tex. 2007), or in making a factual determination lacking evidentiary support, see In re Cerberus Capital Mgmt., L.P., 164 S.W.3d 379, 382 (Tex. 2005) (orig. proceeding).” No. 05-19-00288-CV (July 23, 2019) (mem. op.)

court fails to correctly analyze or apply the law, In re Sw. Bell Tel. Co., L.P., 226 S.W.3d 400, 403 (Tex. 2007), or in making a factual determination lacking evidentiary support, see In re Cerberus Capital Mgmt., L.P., 164 S.W.3d 379, 382 (Tex. 2005) (orig. proceeding).” No. 05-19-00288-CV (July 23, 2019) (mem. op.)

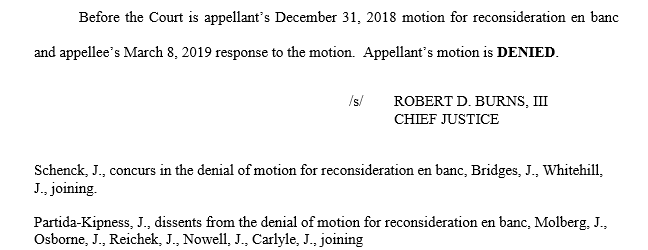

The panel opinion in McPherson v. Rudman affirmed a defense verdict in a medical-malpractice case. The plaintiff sought en banc review, which was denied — barely. Justice Schenck, who wrote the panel opinion, authored a strongly-written concurrence; Justice Partida-Kipness’s dissent was joined by five of the other Democratic Justices.

A valet’s ill-advised joyride in a customer’s limited-edition Mazda Miata led to the case of Parking Co. of Am. Valet, Inc. v. Fellman. Among other holdings, the Fifth Court noted:

A valet’s ill-advised joyride in a customer’s limited-edition Mazda Miata led to the case of Parking Co. of Am. Valet, Inc. v. Fellman. Among other holdings, the Fifth Court noted:

- Publicly-available sales price data. An expert’s use of asking prices from websites like cars.com was acceptable when: “This case does not involve natural gas, real estate, or other market where the sales price of comparable property is readily determinable.”

- Relevance of later sale. “[T]he car was not in the same condition when it was sold as it was before the accident; the evidence showed it was in better condition. Between the accident and the sale, Fellman spent about $1,000 upgrading the

car’s brakes, and he put new tires on the car shortly before he sold it.”

05-17-01277-CV (July 31, 2019) (mem. op.)