Prime argued that fraudulent inducement tolled limitations on its fraud claims, citing an email in which the defendant said: “I ask that you extend this [deadline] to at least 90 days or some other requirement so we have the chance to find another investor, do the paperwork, and get his funding.” The Fifth Court disagreed, stating that the “request to extend the time to ninety days by itself is simply not a representation, promise, or an agreement that would extend the accrual of a cause of action.” Prime United Petroleum Holding Co., LLC v. Malameel, LLC, No. 05-20-00032-CV (Aug. 24, 2021) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original).

Monthly Archives: August 2021

The Texas Supreme Court’s longtime staff attorney for public information, Osler McCarthy, retires on August 31 after many years of dedicated service. I wanted to salute his hard work and share a well-written tribute to him recently prepared by former Chief Justice Wallace Jefferson.

The Texas Supreme Court’s longtime staff attorney for public information, Osler McCarthy, retires on August 31 after many years of dedicated service. I wanted to salute his hard work and share a well-written tribute to him recently prepared by former Chief Justice Wallace Jefferson.

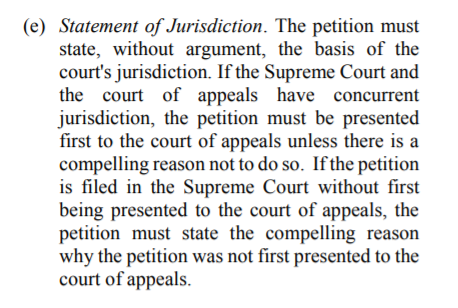

Footnote 3 in the recent en banc majority opinion from Steward Health Care System v. Saidara suggests a promising special exception in cases with general allegations about unfair competition:

Appellants do not specify the branch of “unfair competition” they allege. See, e.g., James E. Hudson, III, A Survey of the Texas Unfair-Competition Tort of Common-Law Misappropriation, 50 BAYLOR L. REV. 921, 924–26 (1989) (noting Texas common law recognizes three branches of unfair competition: palming off, trade-secret misappropriation, and common-law misappropriation); RESTATEMENT (THIRD) OF UNFAIR COMPETITION § 40 cmt. a (AM. LAW INST. 1995) (stating that unfair competition includes torts for misappropriation, infringement, unjust enrichment, and breach of confidence, but not breach of contract, breach of the duty of loyalty owed by an employee or other agent, or breach of confidence not involving a trade secret). Rather, they generally refer to their claim as “Unfair Competition” and contend that “by misleading Steward with their misrepresentations that Prospect intended to buy the assets of Southwest General and thereby inducing Steward to make Southwest General’s most sensitive business information available to Prospect senior executives and ultimately all of Prospect, Prospect and Saidara have engaged in conduct that is contrary to honest practices in commercial matters.”

The panel majority in Winstead PC v. Moore concluded that the TCPA applied to two of three tort claims by a client against his legal counsel, holding that they implicated the firm’s right of petition, while the third did not have a sufficient connection to the exercise of that right. No. 05-20-00050-CV (Aug. 20, 2021). A dissent would have applied the TCPA to all claims and, from there, concluded that the plaintiff failed to meet its burden.

An en banc majority opinion, overruling prior case law to the contrary, held “that the plaintiff must meet its initial burden on a special appearance by pleading, in its petition, sufficient allegations to invoke jurisdiction under the Texas long-arm statute.” (emphasis in original). (Relatedly, under the relevant supreme court precedent, “[t]he plaintiff’s response to the special appearance may contain evidence supporting the petition’s jurisdictional allegations, but that evidence must be consistent with the allegations in the petition.”) Steward Health Care System LLC v. Saidara, No. 05-19-00274-CV (Aug. 20, 2021). Other opinions were written.

Quintanilla v. ANG Rental Holdings, provides a cautionary note about proving up attorneys’ fees, even in the relative informality of a bench trial on frequently litigated issues:

- The appeal arose from a de novo retrial, to the bench, of an FED action in county court; as a result, “an appellant may raise a no-evidence point for the first time on appeal.”

- The record was silent as to (a) an 11-day notice required by the statute allowing fee recovery, and more basically (b) “no evidence of a written lease that entitles ANG to recover attorney’s fees.”

- Why? Because “the lease agreement was excluded from evidence because of the [tenants’] objection, and ANG made no according offer of proof or bill of exception.”

No. 05-20-00062-CV (Aug. 16, 2021) (mem. op.).

Relying on my fortune-telling skills (right) , I offer these thoughts on the recent Texas Supreme Court orders in the ongoing mask litigation:

, I offer these thoughts on the recent Texas Supreme Court orders in the ongoing mask litigation:

- The court could have effectively ended the litigation with a complete stay, as it did last week in the “arrest the legislators” case.

- It didn’t do that. Instead, it let temporary injunction hearings go forward in both Bexar and Dallas Counties. The Bexar hearing is today.

- A decent guess is that there is division of opinion on the court and this order is a rough compromise, among: (a) Justices who would have ruled for the Governor (who “got something” in the form of the initial TROs being vacated; (b) Justices who want to further consider the evidence (or lack thereof) (and who “got something” by the TI hearings proceeding; and (c) Justices who were willing to “kick the can down the road” until after the TI hearings.

The Fifth Court affirmed the dismissal, on ecclesiastical-abstention grounds, of a fraud claim about the handling of a sex-abuse claim by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Dallas: “The district court determined that (i) the Dallas Diocese’s Sexual Misconduct Policy (Policy) was ‘an outgrowth of, or so integrally related to, the Dallas Diocese’s dogma that it comprises part of the Dallas Diocese’s religious representations, beliefs, and teachings,’ (ii) Doe’s fraud claim required Doe to prove the Dallas Diocese’s material representations to Doe were false, and (iii) the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States prohibited the trial court from adjudicating the truth or falsity of religious doctrines or beliefs. Because Doe’s claims require resolution of matters of church government, we affirm the judgment of the trial court.” Doe v. Roman Catholic Diocese of Dallas, No. 05-19-00997-CV (Aug. 11, 2021) (mem. op.).

An old lawyers’ adage, sometimes attributed to Carl Sandburg, says in part: “If the facts are against you, argue the law. If the law is against you, argue the facts. …” Such are the battle lines in the Dallas County mask-mandate case now before the supreme court, in which the real-party-in-interest county judge points to an extensive affidavit and the support of several amici, while the SG’s office laser-focuses on the terms of the Government Code.

Clay Jenkins has filed his response to the AG’s mandamus petition to the Fifth Court of Appeals.

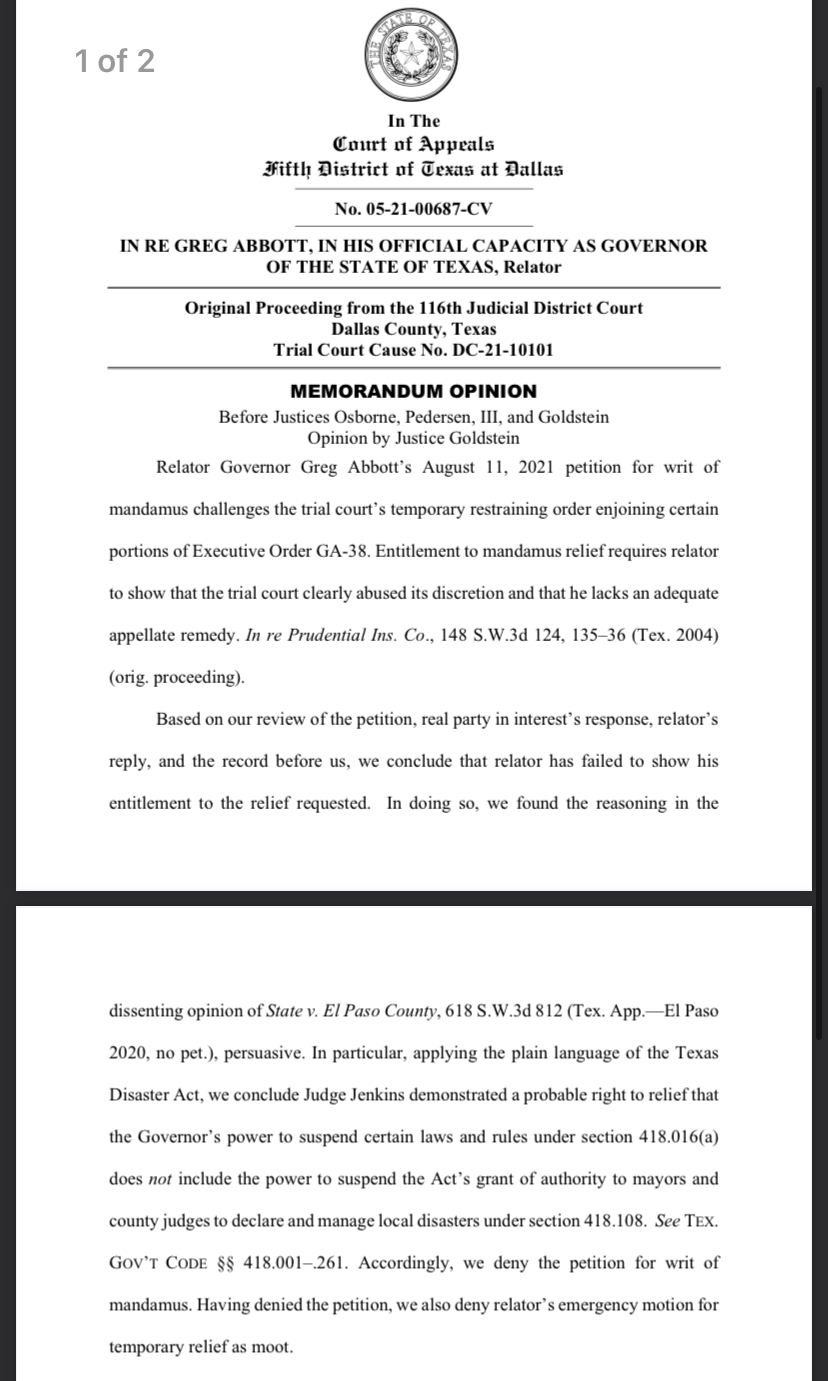

The dispute between Governor Abbott’s GA-38 order, on the one hand, and Judge Tonya Parker’s TRO / County Judge Clay Jenkins’ recent COVID order, on the other, has led to the filing of a mandamus petition in the Fifth Court on the Governor’s behalf. It is accompanied by a request for emergency relief that requests a ruling by Friday afternoon.

While In the Interest of Z.A. involved an issue unique to family law, the relevant facts are instructive about when the denial of a continuance can create reversible error: “Evidence presented at the hearing indicated that E.S.S. [the ‘alleged father’ was indigent and without transportation. Further, he was operating under the faulty assumption that testing would be scheduled in Sherman when he moved there. There was no testing facility in Sherman, however, and the caseworker did not inform him of this fact. And, as of the hearing date, E.S.S. was incarcerated in the Grayson County Jail. Although there is evidence the Department made some attempt to schedule a third appointment at the jail, there is no evidence as to why that did not happen. His attendance at a third appointment would have essentially been assured had it been scheduled to take place at the Grayson County Jail. When E.S.S. presented his motion, he asked the trial court to schedule the genetic testing before terminating his parental rights.” No. 05-21-00126-CV (Aug. 6, 2021) (mem. op.).

“An unexplained delay of four months or more can constitute laches and result in denial of mandamus relief. Here, relators did not file the petition for writ of mandamus until July 28, 2021—more than four and a half months from the challenged oral ruling and three months after the trial court signed the complained-of order. We conclude that relators’ unexplained delay bars their right to mandamus relief.” In re Wages & White Lion Investments LLC, No. 05-21-00650-CV (July 30, 2021) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

“An unexplained delay of four months or more can constitute laches and result in denial of mandamus relief. Here, relators did not file the petition for writ of mandamus until July 28, 2021—more than four and a half months from the challenged oral ruling and three months after the trial court signed the complained-of order. We conclude that relators’ unexplained delay bars their right to mandamus relief.” In re Wages & White Lion Investments LLC, No. 05-21-00650-CV (July 30, 2021) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

Two rulings about the crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege were recently reversed, by both the Fifth Circuit and Dallas’s Fifth District, in response to mandamus petitions. (This is a cross-post with 600Camp.com.)

- In the Fifth Circuit: “[A]s Boeing argues, the district court clearly erred in finding that Plaintiffs established a prima facie case that the contested documents were subject to the crime-fraud exception. The district court concluded that the contested documents were reasonably connected to the fraud based on one finding only—that the documents sought ‘f[e]ll within the period Boeing admit to hav[ing] knowingly and intentionally committed “fraud” in the DPA. However, a temporal nexus between the contested documents and the fraudulent activity alone is insufficient to satisfy the second element for a prima facie showing that the crime-fraud exception applies.” In re The Boeing Co., No. 21-40190 (July 29, 2021, unpublished).

- In the Fifth District, the Court noted: “[A] determination at the TCPA stage as to a prima facie showing does not automatically translate to a prima facie showing for purposes of application of the crime–fraud exception to the attorney–client privilege. The exception UDF attempts to invoke is for crime–fraud, not crime–tort.” From there, it declined to follow a broad view of the exception defined by another Texas intermediate court, “and note that, notwithstanding certain language in the [relevant] opinion, the El Paso court continues to apply the elements of common-law fraud when determining the applicability of the crime fraud exception, rather than requiring proof of a false statement only.” In re Bass, No. 05-21-00102-CV (July 30, 2021) (mem. op.).

Mike Nomad (right) would have been at home in Forever Living Products, Int’l, LLC v. AV Europe GMBH, No. 05-20-00558-CV (July 30, 2021), a personal-jurisdiction appeal in which the record failed to show where the defendant corporation was based. The Fifth Court found that the plaintiff’s pleading asserted general jurisdiction over the defendant; the defendant sought to negate that basis for jurisdiction with affidavits about the location of its “nerve center.” The Court found that while the defendant had substantial connections to Germany at other points in time, in the relevant months leading up to the filing of suit its evidence was legally insufficient to negate general jurisdiction:

Mike Nomad (right) would have been at home in Forever Living Products, Int’l, LLC v. AV Europe GMBH, No. 05-20-00558-CV (July 30, 2021), a personal-jurisdiction appeal in which the record failed to show where the defendant corporation was based. The Fifth Court found that the plaintiff’s pleading asserted general jurisdiction over the defendant; the defendant sought to negate that basis for jurisdiction with affidavits about the location of its “nerve center.” The Court found that while the defendant had substantial connections to Germany at other points in time, in the relevant months leading up to the filing of suit its evidence was legally insufficient to negate general jurisdiction:

“AV Europe’s own evidence shows that its managing director has lived in Texas full-time since July 2018. It also shows that since June 2018 AV Europe ‘has been winding down,” which implies some level of activity, and that its activities have included at least the return of unsold products to HW&B. We see no evidence showing the location from which Hardy [the directpr] or any other AV Europe officer (if any) controlled these activities. We therefore conclude that the evidence was legally insufficient to show that AV Europe’s nerve center was outside of Texas from June 2018 until the filing of suit in January 2019.”

The Fifth Court revisited the borderline between “capacity” and “standing” in the context of a claim acquisition from bankruptcy in Obsidian Solutions, LLC v. KBIDC Investments, LLC, No. 05-19-00440-CV (July 30, 2021) (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court revisited the borderline between “capacity” and “standing” in the context of a claim acquisition from bankruptcy in Obsidian Solutions, LLC v. KBIDC Investments, LLC, No. 05-19-00440-CV (July 30, 2021) (mem. op.).

Substantively, the Court reminded: “The issue of standing focuses on whether a party has a sufficient relationship with the lawsuit so as to have a ‘justiciable interest’ in its outcome; in contrast, the issue of capacity ‘is conceived of as a procedural issue dealing with the personal qualifications of a party to litigate.’ … ‘When the issue involves capacity arising from a contractual right, “Texas law is clear, and this court has previously held numerous times, that a challenge to a party’s privity of contract is a challenge to capacity, not standing.”‘” (citations omitted, emphasis added).

Procedurally, the issue was tried by consent, even if the correct label was not applied. “[A]t trial, the issue of whether KBIDC bought the assets out of bankruptcy and which assets were purchased arose during KBIDC’s direct examination of Kent. … The trial court listened to arguments from both sides on their interpretations of the APA before finding that the APA gave ‘authority to the Plaintiff for … the advancement of this suit.’ Given the parties’ arguments and the trial court’s ruling, we conclude that capacity was tried by consent in the trial court.” (emphasis added).