Article VI, clause 2 of the Constitution provides: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

Article VI, clause 2 of the Constitution provides: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; and the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding.”

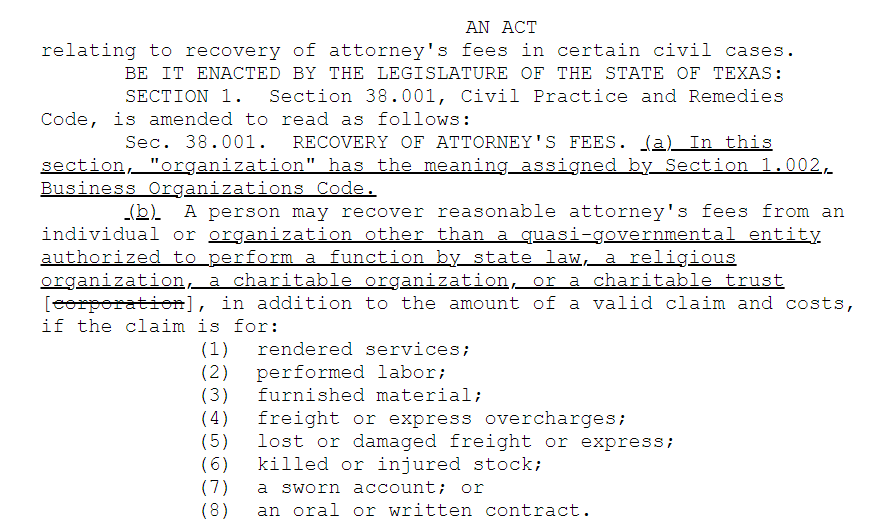

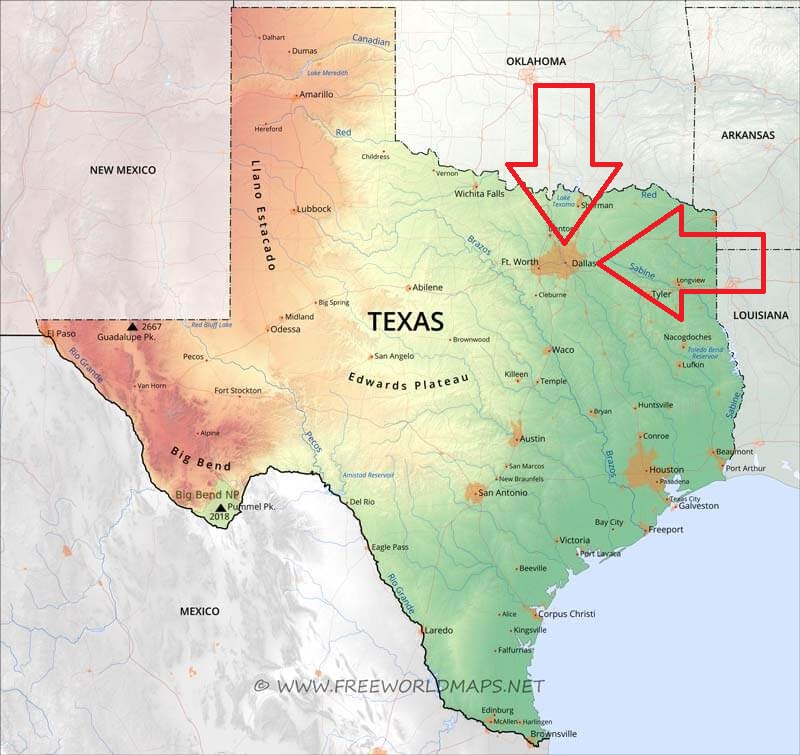

That principle animates the two sides of Toyota Motor Sales v. Reavis, No. 05-19-00075-CV (June 3, 2021), in which a 2-1 Fifth Court majority affirmed a $200+ million judgment in a products-liability case. Greatly simplified, the dispute between majority and dissent can be summarized with two quotes. The majority emphasizes state law and procedure:

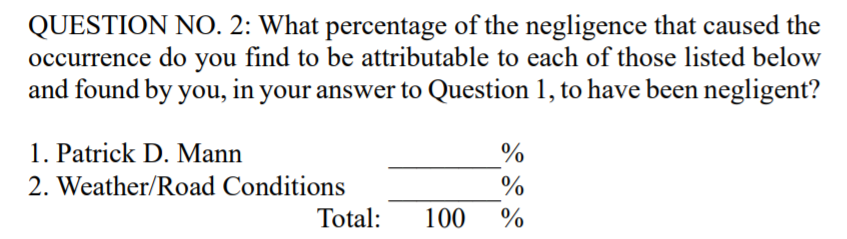

At the heart of this case, like many product liability cases, was a battle of the experts. Plaintiffs’ experts examined physical evidence, performed tests, reviewed data, performed calculations, criticized Toyota Motor’s experts, and concluded the vehicle was defective. Toyota Motor’s experts did the same and concluded the vehicle was not defective. The jury properly exercised its prerogative to resolve this conflicting evidence and believed the plaintiffs’ experts. This Court may not second guess the jury’s decision.

(emphasis added). The dissent, federal regulation:

“The Reavises’ theory of liability—that choosing to design a car with seatback strength far in excess of federal minimum standards and utilizing seatbelt design options permitted after decades of comprehensive federal regulation could support a conclusion that federal regulations are inadequate or that the overall design is defective as a matter of law—is unsustainable. … I accept it as theoretically possible that every car ever marketed and sold to this point could be ‘defective’ and that their manufacturers could all be subject to exemplary damages on this basis, or, that virtually all such cars are defective for failure to employ ‘locking/cinching’ lap belts without regard to seatback rigidity, the proof should be up to the task.”

(footnote omitted, emphasis in original). This dialogue strongly echoes the “two narratives” at play in United States ex rel. Harman v. Trinity Indus., Inc., 872 F.3d 645 (5th Cir. 2017), which reversed a $600+ million judgment based on an allegedly-defective highway guardrail:

The trial in this case offers two narratives. One of a hardworking man who, angered by failures of guardrails installed across the United States — with sometimes devastating consequences — persuaded a Texas jury of a concealed cause of those failures. The other of the inventive genius of professors at Texas A&M’s Transportation Institute, who, over many years of study and testing, developed patented systems including guardrails that, while saving countless lives, cannot protect from all collisions at all angles and all speeds by all vehicles — guardrails that have been installed throughout the United States with an approval from which the government has never wavered as it reimbursed states for the installation of a device integral to the system.