An antitrust case in Tennessee recently produced a remarkably contentious dispute about the definition of “double spacing,” as deftly summarized in this “Above the Law” article titled “Heated Litigation Fight Over Double Spacing Ends in Judge Telling Everyone to Shut Up.” While the dispute was picayune, the discussion of just what exactly “double spacing” means is interesting background for a modern word-processing feature that we seldom stop and think about. Thanks to my law partner Chris Schwegmann for flagging this for me.

Monthly Archives: November 2023

683 is a prime number, as well as a prime reason for reversal of temporary injunctions. Most recently, in a contentious case about the governance of an Eritrean church that presented significant issues about the ecclesiastical abstention doctrine, the Fifth Court resolved the matter on technical grounds by holding that the temporary injunction failed to satisfy the requirements of Tex. R. Civ. P. 683. Teklehaimanot v. Medhanealem Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, No. 05-23-00579-CV (Nov. 17, 2023) (mem. op.).

683 is a prime number, as well as a prime reason for reversal of temporary injunctions. Most recently, in a contentious case about the governance of an Eritrean church that presented significant issues about the ecclesiastical abstention doctrine, the Fifth Court resolved the matter on technical grounds by holding that the temporary injunction failed to satisfy the requirements of Tex. R. Civ. P. 683. Teklehaimanot v. Medhanealem Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church, No. 05-23-00579-CV (Nov. 17, 2023) (mem. op.).

Wakefield, a party to a civil lawsuit, disputed a judgment against him in favor of Rubio, forensic expert retained by his counsel in that lawsuit. Wakefield argued that no evidence established a contract between him and the expert. But the identify of his counsel was undisputed (thus providing some evidence of agency), and additional evidence showed that he ratified his counsel’s dealings with the expert, establishing that he chose to proceed:

Wakefield, a party to a civil lawsuit, disputed a judgment against him in favor of Rubio, forensic expert retained by his counsel in that lawsuit. Wakefield argued that no evidence established a contract between him and the expert. But the identify of his counsel was undisputed (thus providing some evidence of agency), and additional evidence showed that he ratified his counsel’s dealings with the expert, establishing that he chose to proceed:

… after (1) learning Tadlock engaged Rubio to perform expert services with respect to his case, (2) understanding how important the admissibility of evidence from the watch was, (3) personally delivering the watch to Rubio, (4) instructing Rubio to do as his attorney instructed, and (5) learning upon his arrival at the courthouse for his hearing that Rubio’s bill was approaching $10,000.

Wakefield v. Rubio Digital Forensics LLC, Nov. 21, 2023 (mem. op.).

Huffman Asset Management, LLC v. Colter, No. 05-22-00779-CV (Nov. 7, 2023) (mem. op.), a default-judgment case that I recently discussed for its analysis of substituted service, also provided two useful reminders about legal-sufficiency challenges to damages awarded in a default judgment:

Huffman Asset Management, LLC v. Colter, No. 05-22-00779-CV (Nov. 7, 2023) (mem. op.), a default-judgment case that I recently discussed for its analysis of substituted service, also provided two useful reminders about legal-sufficiency challenges to damages awarded in a default judgment:

- Insufficient proof = no damage. “While those statements provide some evidence of the Colters’ belief they suffered mental anguish, the testimony does not show the nature, duration, and severity of the mental anguish, a substantial interruption in the Colters’ daily routine, or a high degree of mental pain and distress that is greater than mere worry, anxiety, vexation, embarrassment, or anger. The affidavits also include no evidence to justify the amount awarded. We, therefore, … sustain HAM and Prairie Capital’s fifth issue in part by reversing the mental anguish damages awarded to the Colters.”

- Insufficient proof = remand, not rendition. “We do not, however, render a take nothing judgment against the Colters as to the mental anguish damages. ‘[W]hen an appellate court sustains a no evidence point after an uncontested hearing on unliquidated damages following a no-answer default judgment, the appropriate disposition is a remand for a new trial on the issue of unliquidated damages.’ …

in a no-answer default judgment, remand is necessary only as to the categories of

damages for which the evidence presented was insufficient.”

The plaintiff in Vallejo v. Helge, faced with a dismissal for want of prosecution, timely filed a motion to reinstate and then obtained a default judgment.

The plaintiff in Vallejo v. Helge, faced with a dismissal for want of prosecution, timely filed a motion to reinstate and then obtained a default judgment.

So far so good. But the defendant appealed, and the Fifth Court noted that the motion to reinstate was not verified–a requirement of the relevant rule and supreme court precedent. The motion was thus ineffective, which meant that the Court had to then “vacate the void judgment and dismiss the appeal.” No. 05-23-00573-CV (Nov. 15, 2023) (mem. op.).

The supreme court has consistently rejected discovery requests as overbroad that seek requests about “other similar accidents,” etc. when the requested information is not obviously connected to the facts of the case at hand. In In re Liberty County Mut. Ins. Co., the supreme court clarified that discovery about a plaintiff’s other accidents and injuries is discoverable when it is relevant to proof of causation and damages. While the specific holding of this case is tied to personal-injury litigation, its logic applies to other types of discovery disputes as well. No. 22-0321 (Tex. Nov. 17, 2023).

The supreme court has consistently rejected discovery requests as overbroad that seek requests about “other similar accidents,” etc. when the requested information is not obviously connected to the facts of the case at hand. In In re Liberty County Mut. Ins. Co., the supreme court clarified that discovery about a plaintiff’s other accidents and injuries is discoverable when it is relevant to proof of causation and damages. While the specific holding of this case is tied to personal-injury litigation, its logic applies to other types of discovery disputes as well. No. 22-0321 (Tex. Nov. 17, 2023).

The Fifth Court reversed the grant of a Rule 91a motion on issues involving limitations, privity, and standing, in 17714 Bannister v. TAS Env. Servcs. LP, No. 05-22-00820-CV (Nov. 9, 2023) (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court reversed the grant of a Rule 91a motion on issues involving limitations, privity, and standing, in 17714 Bannister v. TAS Env. Servcs. LP, No. 05-22-00820-CV (Nov. 9, 2023) (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court reviewed the interplay between the COVID pandemic and a “force majeure” clause in a commercial lease in BB Fit v. EREP Preston Trail II:

The Fifth Court reviewed the interplay between the COVID pandemic and a “force majeure” clause in a commercial lease in BB Fit v. EREP Preston Trail II:

[T]he parties expressly agreed that delays due to enumerated causes beyond the parties’ reasonable control would be excluded from computations of time. They did not agree to discharge BB FIT’s obligation to pay rent; to the contrary, Lease § 4(d) provides that “[t]he obligation of Tenant to pay Rent and the obligations of Tenant to perform other covenants and duties hereunder constitute independent and unconditional obligations of Tenant to be performed at all times as provided hereunder.” We conclude these express terms govern, specifically providing for an extension of time to pay rent rather than a discharge of the obligation.

No. 05-22-00682-CV (Nov. 9, 2023). (Our firm represented the successful party.)

Service on uncooperative individuals often requires a motion for substituted service. For Texas-chartered business entities, the Secretary of State is an option, and in Huffman Asset Managment v. Colter the Fifth Court rejected an argument that the Secretary is required to serve process anywhere other than the designated addresses:

Service on uncooperative individuals often requires a motion for substituted service. For Texas-chartered business entities, the Secretary of State is an option, and in Huffman Asset Managment v. Colter the Fifth Court rejected an argument that the Secretary is required to serve process anywhere other than the designated addresses:

Under HAM and Prairie Capital’s interpretation of section 5.253, the Secretary of State would be required to ignore an entity’s filings concerning its registered agent and registered office in favor of information contained in a more recent filing that is unrelated to service of process and does not designate or change a registered agent, registered office, or their accompanying addresses. Such an interpretation ignores the overarching requirement that corporations maintain a registered agent and registered office for service of process and keep the addresses of both updated with the Secretary of State.

No. 05-22-00779-CV (Nov. 7, 2023).

The Byzantine rules about post-trial requests for findings of fact and conclusions of law were enforced by the Fifth Court in Mangum v. Mangum: “In his first issue, Roderick challenges the trial court’s failure to file findings of fact and conclusions of law despite his timely request and a subsequent notice of late findings of fact. Although his original request was timely filed, the notice of late findings was filed more than 30 days later and did not preserve this issue for appellate review.” No. 05-22-01118-CV (Oct. 31, 2023) (mem. op.).

The Byzantine rules about post-trial requests for findings of fact and conclusions of law were enforced by the Fifth Court in Mangum v. Mangum: “In his first issue, Roderick challenges the trial court’s failure to file findings of fact and conclusions of law despite his timely request and a subsequent notice of late findings of fact. Although his original request was timely filed, the notice of late findings was filed more than 30 days later and did not preserve this issue for appellate review.” No. 05-22-01118-CV (Oct. 31, 2023) (mem. op.).

In U.S. Polyco, Inc. v. Texas Central Business Lines Corp., the Texas Supreme Court reversed a contract case based on the definition of ambiguity. The court also rejected an argument for affirmance based on “context,” stating:

The task of harmonizing contracts entails reconciling otherwise conflicting contractual provisions. That task does not authorize courts to ensure that every provision comports with some grander theme or purpose, particularly when the parties have not said in the contract which purpose matters most or that everything else in thecontract should be read subject to that purpose. To hold otherwise would implicitly assume that contracting parties pursue a purpose (at whatever generality) at all costs.

No. 22-0901(footnote omitted).

Note that this concept is distinct from “commercial context”–the circumstances surrounding the execution of a contract, within the reasonable awareness of parties. See, e.g., Kachina Pipeline Co. v. Lillis, 471 S.W.3d 445 (Tex. 2015) (“We may consider the facts and circumstances surrounding a contract, including ‘the commercial or other setting in which the contract was negotiated and other objectively determinable factors that give context to the parties’ transaction.'” (citation omitted)).

In U.S. Polyco, Inc. v. Texas Central Business Lines Corp., the Texas Supreme Court reviewed a contract dispute, and gave a reminder about a basic principle of contract interpretation.

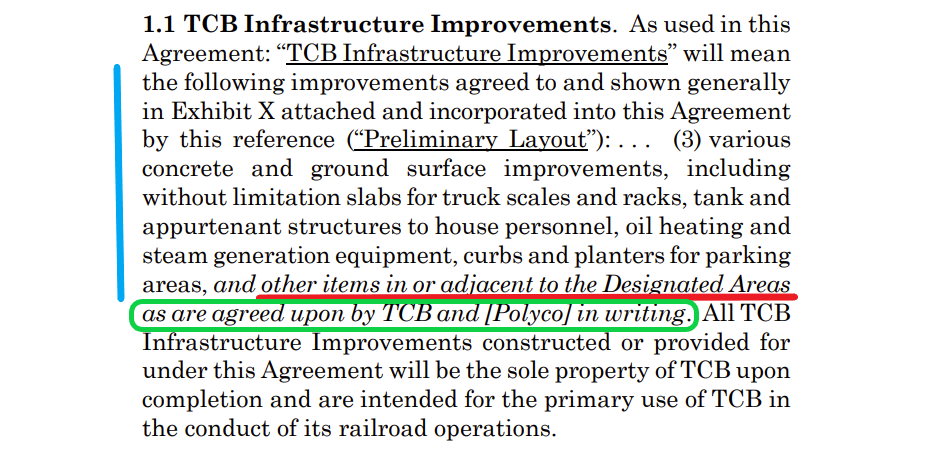

The dispute involved the below language about “other items … as are agreed upon by TCB and [Polyco] in writing” (green, below).

One side contended that it applied only to the “other items” Designated Areas” referred to earlier in the clause (red, below). The other argued that it reached all items listed in the full paragraph (blue, below):

The trial court, court of appeals, and supreme court all agreed that the bettter reading of the “in writing” clause was that it only related to the “other items” (noting, among other matters, the importance of the “Oxford comma”). But the court of appeals found ambiguity, based on its characterization of the parties’ dueling interpretations as reasonable, and that is the point on which the supreme court reversed:

This analysis is erroneous for two basic reasons. First, like all other considerations beyond the contract’s language and structure, parties’ “disagreement” about their intent is irrelevant to whether that text is ambiguous. Parties who find themselves in a business dispute can always claim an extratextual “intent” that would serve a current litigation position. Second, the “multiple, reasonable interpretations” that the court of appeals invoked are illusory. If there were multiple interpretations and a court could not choose among them, then the text would be genuinely ambiguous and there would be no choice but to leave the question to a jury. But the multiple interpretations that the court was referencing here were merely the competing theories that the parties advanced about how to read the text—a dispute that both the trial and appellate courts had ably addressed as a matter of law.

No. 22-0901 (Nov. 3, 2023) (emphasis removed).