The capable Doug Gladden posted this remarkable story on X about an appointed attorney in a criminal appeal who repeatedly recycles the same two, stale arguments — and explains why that practice has led to considerable injustice.

Monthly Archives: June 2024

Brown v. Joe Jordan Trucks, Inc. involved a claim that the wrong Frederick Altyman Brown may have been named in the citation by the elimination of “, Jr.” after the defendnant’s name. The Fifth Court disagreed:

In the present case the petition, citation and return all identify the defendant as “Frederick Altyman Brown.” The designation or suffix “Jr.” is a nonessential part of the defendant’s name for purposes of service of process, and the omission of said designation or suffix does not render the defendant’s name misstated, rather the omission merely renders the defendant’s name abbreviated in a common form.

No. 05-23-00676-CV (June 20, 2024) (mem. op.).

Deaguero v. Commission for Lawyer Discipline repeatedly reminds of the importance of bringing forward a complete record–for example, when challenging a summary judgment ruling, it’s a problem when “the appellate record does not include the Commission’s motion, Deaguero’s response, or the order granting partial summary judgment.” No. 05-22-01002-CV (March 28, 2024).

Hernandez v. Ayala involved a dispute about the value of a “barndominium“–basically, a barn that you can live in–and turned on the “property owner” rule about testimony as to value:

Ayala provided no basis for his valuations of the property. He did not testify that he was familiar with the market value of the partnership property or otherwise explain how he determined the value of each item, except for his testimony that an appraiser told him the barndominium was worth $120,000.

No. 05-23-00549-CV (June 18, 2024).

The supreme court’s recent opinion in Pay & Save, Inc. v. Canales involved a grocery-store customer who got his foot stuck in a forklift pallet used to display watermelons.

The supreme court’s recent opinion in Pay & Save, Inc. v. Canales involved a grocery-store customer who got his foot stuck in a forklift pallet used to display watermelons.

The court of appeals was unimpressed with the plaintiff’s case, but distinguished between legal and factual sufficiency in its analysis, and thus remanded for a new trial instead of rendering judgment for the defendant. As the supreme court summarized:

“The court of appeals correctly recognized that the evidence shows only ‘a possibility that someone’s foot might enter a pallet opening.’ It still erroneously concluded, however, that such evidence is legally sufficient evidence of an unreasonably dangerous condition. In doing so, it reasoned that ‘the jury could have reasonably inferred that a customer could get a foot stuck in a pallet side opening, which could cause the customer to fall and be injured.’”

The supreme court disagreed, characterized the problem as ine of legal sufficiency, and rendered judgment for the defendant:

“The court of appeals’ error was twofold. First, it assumed that a mere possibility of harm suffices to legally establish the existence of an unreasonable risk of harm. Second, it assumed that it needed to credit the jury’s flawed inference to that effect. We have long held to the contrary. … As the evidence shows only a mere possibility of harm, it is legally insufficient.”

No. 22-0953 (Tex. June 14, 2024) (per curiam).

In re State of Texas helpfully clarifies the standard for when temporary relief is appropriate during the pendency of an appeal. Eliminating some uncertainty that had crept into the sparse case law about this topic, the supreme court observed:

In re State of Texas helpfully clarifies the standard for when temporary relief is appropriate during the pendency of an appeal. Eliminating some uncertainty that had crept into the sparse case law about this topic, the supreme court observed:

Rather than describe the purpose of relief under Rule 52.10 as “preservation of the status quo,” we find Rule 29.3’s analogous formulation more helpful. An appellate court asked to decide whether to stay a lower court’s ruling pending appeal or to stay a party’s actions while an appeal proceeds should seek “to preserve the parties’ rights until disposition of the appeal.” The equitable authority weexercise today, under Rule 52.10, serves the same purpose—preservation of the parties’ rights while the appeal proceeds. A stay pending appeal is, of course, a kind of injunction, so the familiar considerations governing injunctive relief in other contexts will generally apply in this context as well.

No. 24-0325 (Tex. June 14, 2024). The court then examined how those general equitable considerations–including likelihood of success on the merits–applied in that case. This clarification of the law serves to generally align Texas and federal practice on the issue of appellate stays (setting aside the hot-button topic of “administrative stays”).

The Fifteenth Court’s new judges do not start empty-handed when it comes to precedent, as that Court has several sources of precedent to draw upon by operation of law.

The Fifteenth Court’s new judges do not start empty-handed when it comes to precedent, as that Court has several sources of precedent to draw upon by operation of law.

Governor Abbott has announced the judges of the Dallas Division of the new business court–Hon. Andrea Bouressa of Collin County, and appellate stalwart Bill Whitehill of Dallas.

Governor Abbott has announced the judges of the Dallas Division of the new business court–Hon. Andrea Bouressa of Collin County, and appellate stalwart Bill Whitehill of Dallas.

Governor Abbott has appointed the three inaugural members of the new Fifteenth Court of Appeals: Hon. Scott Brister, presently of Hunton Andrews Kurth, well-known statewide from his service on the Texas Supreme Court, and the author of City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802 (Tex. 2005); Hon. April Farris, of the First Court of Appeals; and Hon. Scott Field, of the 480th District Court in Williamson County, and formerly of the Third Court of Appeals.

Governor Abbott has appointed the three inaugural members of the new Fifteenth Court of Appeals: Hon. Scott Brister, presently of Hunton Andrews Kurth, well-known statewide from his service on the Texas Supreme Court, and the author of City of Keller v. Wilson, 168 S.W.3d 802 (Tex. 2005); Hon. April Farris, of the First Court of Appeals; and Hon. Scott Field, of the 480th District Court in Williamson County, and formerly of the Third Court of Appeals.

At issue in Robinson v. Boral Windows LLC was the scope of a release, which addressed “any and all actions … from the beginning of time to the present, including any and acts or omissions occurring to date … specifically includ[ing] without limitation all matters arising out of … the Employment Agreement ….” After a comprehensive review of case law involving similar terms, the Fifth Court held:

At issue in Robinson v. Boral Windows LLC was the scope of a release, which addressed “any and all actions … from the beginning of time to the present, including any and acts or omissions occurring to date … specifically includ[ing] without limitation all matters arising out of … the Employment Agreement ….” After a comprehensive review of case law involving similar terms, the Fifth Court held:

- The release was not limited to the identified Employment Agreement, given the other, broader language in the release;

- For similar reaons, the release included claims based on two other instruments, even thought they were not specificaly identified in the release;

- The release extended to a successor-in-interest to one of the parties, by operation of law and because it had a standard “all predecessors, successors [and] assigns” clause.

No. 05-22-01184-CV (June 10, 2024) (mem. op.).

A popular meme shows Oprah Winfrey giving cars away to everyone in sight. In Pack Properties XIV, LLC v. Remington Prosper, LLC, the Fifth Court found fact issues all ’round, and held that all parties summary-judgment motions should be denied in a dispute about a contract related to the establishment of a car dealership. Two key points were:

A popular meme shows Oprah Winfrey giving cars away to everyone in sight. In Pack Properties XIV, LLC v. Remington Prosper, LLC, the Fifth Court found fact issues all ’round, and held that all parties summary-judgment motions should be denied in a dispute about a contract related to the establishment of a car dealership. Two key points were:

- Under Fifth Court precedent, the term “affiliate” in a contract “is generally defined as a ‘corporation that is related to another corporation by shareholdings or other means of control’ and as a ‘company effectively controlled by another or associated with others under common ownership or control.'” Applying that precedent, the record presented a fact issue about “whether sufficient control” existed among the relevant parties.

- “Materiality” arises in two distinct settings. In one, “a court must determine if the parties’ agreement is sufficiently certain to be an enforceable contract. The question generally arises when the agreement lacks a particular term or contains a term that is unclear. The ultimate issue in this kind of case is the existence of a valid contract, which is a legal question.” In the other, “the question is whether a breach by one party was sufficiently important to excuse the other party’s continuing performance, i.e., the affirmative defense of prior material breach. These cases do not address a missing term and its effect on the validity of a contract; instead, these cases look to the significance of a particular term within the total agreement. Courts performing this analysis address the materiality issue as a fact question.”

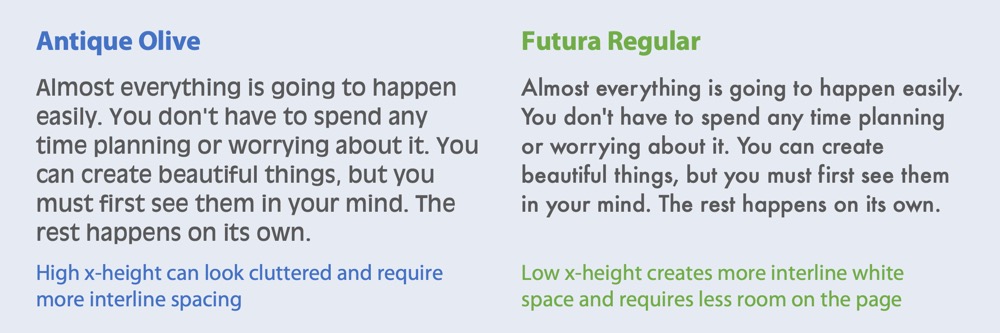

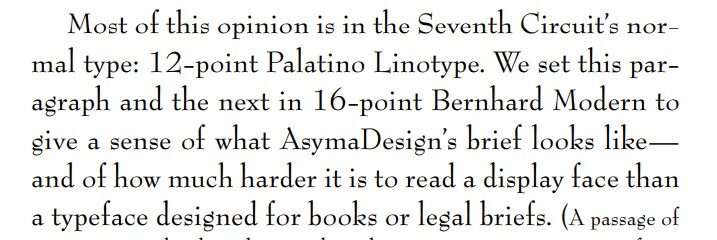

Judge Easterbrook’s recent opinion about good fonts for legal writing emphasized the importance of “x-height,” which is the relative size of a small “x” to a capital letter in a particular font. It’s important to note, though, that x-height is only one of the relevant size measures, and an excessively high x-height can cause problems with “descending” letters such as “p” and “y.” This excellent article, from which the below illustration is taken, further explains this point while defining the other relevant measurements.

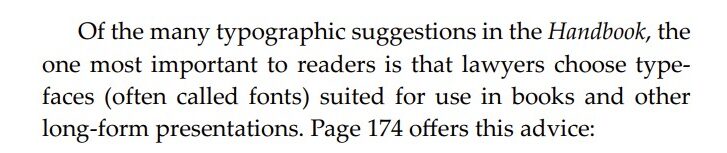

Legendary Seventh Circuit judge Frank Easterbrook has written authoritatively on many topics. Thanks to AsymaDesign, LLC v. CBL & Assocs. Mgmnt, Inc., the choice of a good font is now among them.

Judge Easterbrook noted that he was writing in Palatino Linotype, the standard font of the Seventh Circuit (and one of two that I regularly use, alternating with Book Antigua). He explained that it’s a desirable font for legal writing because it has a large “x-height” (the height of a lowercase “x” compared to a capital letter), along with similar fonts designed for book publication:

The Appellant made the unfortunate choice of Bernhard Modern, a “display face suited to movie posters and used in the title sequence of the Twilight Zone TV show.” Because of that font’s low x-height, it’s hard to read in book-like writing:

The Appellant made the unfortunate choice of Bernhard Modern, a “display face suited to movie posters and used in the title sequence of the Twilight Zone TV show.” Because of that font’s low x-height, it’s hard to read in book-like writing:

He concluded: “We hope that Bernhard Modern has made its last appearance in an appellate brief. “

He concluded: “We hope that Bernhard Modern has made its last appearance in an appellate brief. “

Claim preclusion barred a second lawsuit for unpaid rent, when the record showed as to an earlier lawsuit that:

When appellants filed the previous lawsuit, the lease entitled them, in part, to three categories of damages: (1) rent unpaid before termination, (2) rent unpaid after the lease’s termination and before appellants receive judgment therefor, “and” (3) “unpaid rent called for under the Lease for the balance of the term[.]” Moreover, appellants cite judicial opinions that provide a landlord may sue for future damages upon breach of lease. Consequently, appellants “could have” alleged in the previous lawsuit a claim seeking judgment for all three categories of damages authorized by the lease. Instead, appellants alleged and recovered in the previous lawsuit only part of their claim by seeking solely unpaid rent that had accrued prior to the previous judgment.

(citations omitted). The judgment in the earlier case had a clause that said: “This Judgment does not preclude Plaintiffs from seeking additional damages as they accrue after December 2020.” That language didn’t change the Fifth Court’s ruling, however:

[A]ppellants “terminated” the lease August 5, 2020, and the lease expressly authorized appellants to seek damages they seek in this lawsuit at the time they terminated the lease. Consequently, appellants’ claim for the damages they claim in this lawsuit accrued—came into existence as a legally enforceable claim—on August 5, 2020, when they terminated the lease and before they filed the previous lawsuit. Therefore, we conclude the recital in the previous judgment concerning claims that “accrue after December 2020” cannot apply to appellants’ claim for damages for breach of lease in this lawsuit, which accrued August 5, 2020, prior to the previous lawsuit and judgment.

SJF Forest Lane LLC v. Phan, No. 05-22-00905-CV (May 31, 2024) (citation omitted).