Ambiguity 101

November 5, 2023In U.S. Polyco, Inc. v. Texas Central Business Lines Corp., the Texas Supreme Court reviewed a contract dispute, and gave a reminder about a basic principle of contract interpretation.

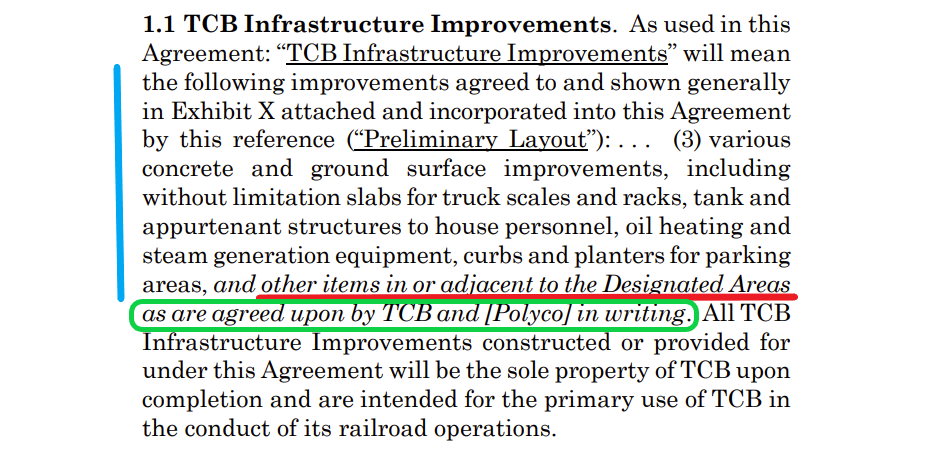

The dispute involved the below language about “other items … as are agreed upon by TCB and [Polyco] in writing” (green, below).

One side contended that it applied only to the “other items” Designated Areas” referred to earlier in the clause (red, below). The other argued that it reached all items listed in the full paragraph (blue, below):

The trial court, court of appeals, and supreme court all agreed that the bettter reading of the “in writing” clause was that it only related to the “other items” (noting, among other matters, the importance of the “Oxford comma”). But the court of appeals found ambiguity, based on its characterization of the parties’ dueling interpretations as reasonable, and that is the point on which the supreme court reversed:

This analysis is erroneous for two basic reasons. First, like all other considerations beyond the contract’s language and structure, parties’ “disagreement” about their intent is irrelevant to whether that text is ambiguous. Parties who find themselves in a business dispute can always claim an extratextual “intent” that would serve a current litigation position. Second, the “multiple, reasonable interpretations” that the court of appeals invoked are illusory. If there were multiple interpretations and a court could not choose among them, then the text would be genuinely ambiguous and there would be no choice but to leave the question to a jury. But the multiple interpretations that the court was referencing here were merely the competing theories that the parties advanced about how to read the text—a dispute that both the trial and appellate courts had ably addressed as a matter of law.

No. 22-0901 (Nov. 3, 2023) (emphasis removed).