Texas law favors arbitration agreements – but even the most favorable view of the topic requires an agreement. In Exencial Wealth Advisors, LLC v. Sipes, the relevant contract required a signature to become effective, and the record did not contain a signed copy of that instrument. Therefore, the contract failed for lack mutual assent, and arbitration of the parties’ dispute was not required. No. 05-24-00964-CV (Jan. 31, 2025) (mem. op.).

Texas law favors arbitration agreements – but even the most favorable view of the topic requires an agreement. In Exencial Wealth Advisors, LLC v. Sipes, the relevant contract required a signature to become effective, and the record did not contain a signed copy of that instrument. Therefore, the contract failed for lack mutual assent, and arbitration of the parties’ dispute was not required. No. 05-24-00964-CV (Jan. 31, 2025) (mem. op.).

Category Archives: Arbitration

Mandamus issued in a failure-to-rule case when: “Megatel filed its motion to compel arbitration on June 30, 2022, and the motion was initially set for hearing two years ago on November 2, 2022. For various reasons and despite three hearings, two additional settings, and multiple requests, the trial judge failed to rule on the motion to compel arbitration and instead set a jury trial date.” In re Megatel, No. 05-24-01161-CV (Nov. 18, 2024).

An arbitration provision was not illusory when:

“[T]he arbitration provisions apply equally to all parties. The arbitration provisions cannot be amended or terminated unilaterally by the LPs—that would require the approval of partners owning the requisite supermajority of capital interests under the partnership agreements. As previously discussed, amendments to partnership agreements may be duly adopted in accordance with the terms of the partnership agreement to which the limited partner initially agreed.”

Caprocq Core Real Estate Fund, LP v. Essa K. Alley Revocable Trust No. 2, No. 05-22-01021-CV (Oct. 25, 2024) (mem. op.).

The Texas Supreme Court rejected a challenge to the unconscionabilty of an arbitration award (and thus, the delegation of arbitrability to the arbitrator) in Lennar Homes of Texas Inc. v. Rafiei, No. 22-0830 (Tex. Apr. 4, 2024). The challenge involved the cost of arbitration; the Court held:

Rafiei has presented no evidence that he sought a deferral or reduction of the administrative fees or an agreement to proceed with a single arbitrator. Without evidence that Rafiei sought to estimate the actual costs associated with arbitrating the arbitrability question, it is speculative to conclude that the delegation provision is itself unconscionable.

Zurvita Holdings, Inc. v. Jarvis offers a detailed analysis of an arbitration-waiver issue. Its holdings are, inter alia:

Zurvita Holdings, Inc. v. Jarvis offers a detailed analysis of an arbitration-waiver issue. Its holdings are, inter alia:

- In its 2023 TotalEnergies opinion, the supreme court clarified “who decides arbitrability when the agreement incorporates the AAA or similar rules that delegate arbitrability to the arbitrator,” but “dot not address waiver of the right to arbitrate.”

- “[A]n agreement that is silent about arbitraing claims against non-signatories does not unmistakably mandate arbitration or arbitrability in such cases.”

- “Substantial invocation of the judicial process” was established by a record involving an 11-month delay in asserting an arbitraion right, actively pursuing expedited discovery, and pursuing a summary judgment motion. (Consistent with current Texas law, the Court also reviewed whether the delay caused prejudice–an issue that the Texas Supreme Court is likely to consider after the U.S. Supreme Court recently did away with that additional waiver requirement under the Federal Arbitration Act.)

No. 05-23-00661-CV (March 14, 2024) (mem. op.)

The settlement agreement in Clendening v. Blucora, Inc. resolved an arbitration by requiring a series of settlement payments by one party (the former employer), conditioned on the acceptable provision of information by the other (the former employee). The arbitrator “retain[ed] jurisdiction” to hear a dispute about the adequacy of that information and order a deposition “to occur not later than February 27, 2022.”

The settlement agreement in Clendening v. Blucora, Inc. resolved an arbitration by requiring a series of settlement payments by one party (the former employer), conditioned on the acceptable provision of information by the other (the former employee). The arbitrator “retain[ed] jurisdiction” to hear a dispute about the adequacy of that information and order a deposition “to occur not later than February 27, 2022.”

A dispute arose, and the arbitrator ordered a deposition to occur after February 27. The Fifth Court held that this award exceeded the arbitrator’s powers and vacated it. No. 05-22-01190-CV (March 7, 2024) (mem. op.).

This language was sufficient–notwithstanding additional, similar language in other cases on the point–to allow a right of appeal from an artbitration award under the Texas Arbitration Act:

This language was sufficient–notwithstanding additional, similar language in other cases on the point–to allow a right of appeal from an artbitration award under the Texas Arbitration Act:

Notwithstanding the applicable provisions of Texas law the parties agree that the decision of the arbitrator and the findings of fact and conclusions of law shall be reviewable on appeal upon the same grounds and standards of review as if said decision and supporting findings of fact and conclusions of law were entered by a court with subject matter and present jurisdiction.

Multi-Housing Tax Credit Partners XXXI v. White Settlement Senior Living, LLC, No. 05-22-00721-CV (Jan. 26, 2024) (mem. op.).

In the atypical setting of an appeal from an arbitration award (under the TAA), the Fifth Court concluded that the price set by an option agreement was sufficiently definite:

In the atypical setting of an appeal from an arbitration award (under the TAA), the Fifth Court concluded that the price set by an option agreement was sufficiently definite:

[T]he Option Provision included a formula to determine the purchase price, limiting the purchase price to the greater of the mutually agreed upon appraiser’s calculations, including assumption guidelines for same, or a definite sum of taxes owing, present value of anticipated tax credits not yet received by limited partner, and $100.00. In reaching this conclusion, we reject MHT’s argument that this case is similar to that of Playoff Corp. v. Blackwell, in which the parties entered into an employment contract that promised the employee 25% of a portion of the company’s fair market value upon his termination but did not agree, however, on how the company’s fair market value would be determined, instead agreeing that it would be determined based on a specific formula that the parties would have to agree to in the future after “later negotiations.”

The Court also said: “[W]e agree with other courts that have held that when parties to an agreement specify that a third person is to fix the price, the contract is not unenforceable for lack of definiteness.” Multi-Housing Tax Credit Partners XXXI v. White Settlement Senior Living, LLC, No. 05-22-00721-CV (Jan. 26, 2024) (mem. op.).

The parties’ agreement said that “[Arbitrator’s] determination may not be appealed to any court or other third party but will be binding on all parties.” The Fifth Court held that this language was not a waiver of the right to vacate or modify an award under the Texas Arbitration Act: “[A] waiver of appeal in the arbitration agreement does not preclude judicial review of matters concerning [statutory modification].” Tye v. Shuffield, No. 05-02-00163-CV (Jan. 5, 2024) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

The parties’ agreement said that “[Arbitrator’s] determination may not be appealed to any court or other third party but will be binding on all parties.” The Fifth Court held that this language was not a waiver of the right to vacate or modify an award under the Texas Arbitration Act: “[A] waiver of appeal in the arbitration agreement does not preclude judicial review of matters concerning [statutory modification].” Tye v. Shuffield, No. 05-02-00163-CV (Jan. 5, 2024) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

The Fifth Court rejected a challenge, based on a contract’s venue clause, to the confirmation of an arbitration award, in Picone v. Cruciani:

The Fifth Court rejected a challenge, based on a contract’s venue clause, to the confirmation of an arbitration award, in Picone v. Cruciani:

The concept of venue speaks to the place where a lawsuit is to proceed. See id. It does not speak to the manner in which a dispute will be resolved. Nor is a provision calling for venue in Dallas County courts mutually exclusive from an arbitration provision: even if the parties agree to arbitrate their differences, a court must confirm the arbitrator’s award, and a venue provision determines where that confirmation will take place. The venue provision in the 2020 Release and Settlement has no bearing on the arbitrability of any claim between these parties.

No. 05-22-00841-CV (Dec. 21, 2023) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

The Fifth Court confirmed the confirmation of an arbitration award arising from a dispute about the purchase of a surgical center in Minimally Invasive Surgery Inst., LLC v. MISI Realty CC Dallas, LP. It reminded about two basic points in challenging arbitration awards:

- “‘Manifest disregard of the law‘ is not a valid ground for vacating an arbitration award under the FAA or TAA.”

- “[T]he Final Award notes the four-day arbitration included offers of proof, counsel statements, witness testimony, deposition and documentary evidence, and post-arbitration briefs. The arbitration award also states: ‘All issues have been determined by the evidence presented during the full arbitration.’ The award provides findings and conclusions with analysis. But the record contains little more than the arbitration award, the lease agreement, and the trial court order granting the motion to confirm the arbitration award. There is no list of exhibits or witnesses, no record of exhibits admitted into evidence or rulings on evidentiary objections, and no transcript of the proceedings. The trial court and appellate records do not include a complete record of the arbitration, and what is included is insufficient to allow this Court to conduct a meaningful review of any claimed ‘manifest disregard of the law’ by the arbitrator.”

No. 05-22-00581-CV (Oct. 19, 2023) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

A good example of when direct-benefits estoppel will not support a motion to compel arbitration appears in Strucsure Home Warranty LLC v. 2RH Bros. Props., LLC, where:

“2RH’s third-party petition indicates that its breach of contract claim against StrucSure is based on StrucSure’s alleged breach to provide the Limited Warranty, not a breach of any terms of the Limited Warranty itself.”

No. 05-22-01214-CV (July 17, 2023) (mem. op.).

In the 2021 case of Aerotek v. Boyd, the Texas Supreme Court differed with the Fifth Court about the interplay of evidence rules and the Federal Arbitration Act. That case involved electronic signatures. he Fifth Court returned to this general subject, but on a different issue, in Fox v. Rehab. & Wellness Centre of Dallas, LLC, a wrongful death action against a nursing home.

The supreme court has observed that the statute requires consideration of submitted “affidavits, pleadings, discovery, or stipulations.” Here, “[r]ather than submitting with their motion [to compel arbitration] any ‘affidavits, pleadings, discovery, or stipulations’ to support their motion, appellees attached to their motion only the two-page unauthenticated Agreement, and they submitted no evidence at the later non-evidentiary hearing.” (citation omitted).

The Fifth Court noted its precedent that would allow rejection of the motion on that record, but did not decide on that basis. It instead holding that the record had no evidence establishing the authority of a husband (the plaintiff) to sign the agreement on behalf of his wife (the decedent) – despite a “certification” to that effect in the agreement.

The case presents an interesting return to a potentially fruitful topic for opponents of arbitration–reminding that arbitration rights are favored if proven, but still must be proven. The case also suggests that nursing homes should be careful about documentation, as the requisite power and authority will not always be presumed. No. 05-21-000904-CV (June 5, 2023) (mem. op.).

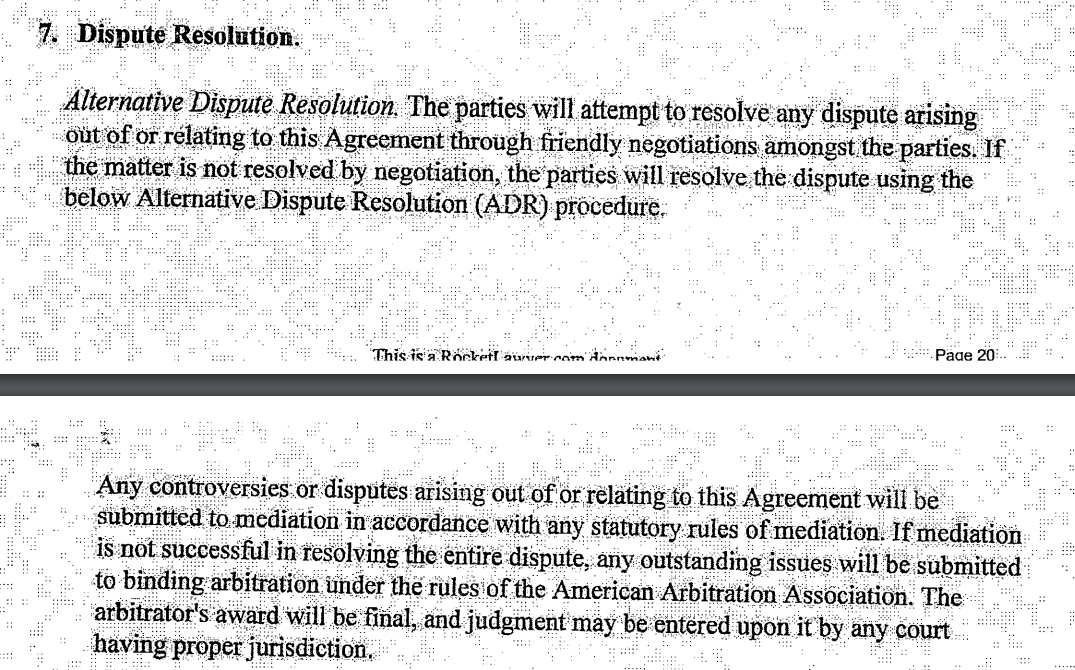

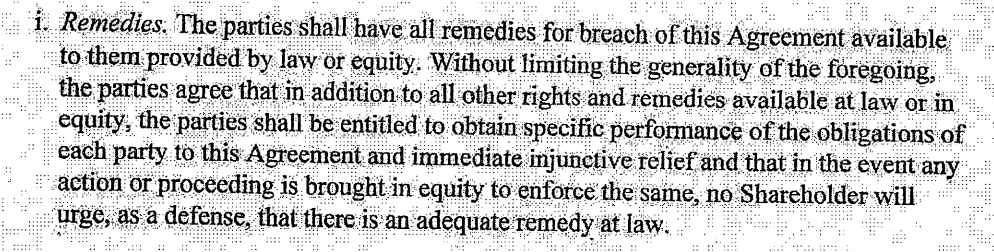

Kirk v. Atkins enforced a straightforward arbitration agreement (my apologies for the tilt, which appears in the original record) with broad, “any dispute” language: despite similarly broad “all remedies” language in another section about remedies:

despite similarly broad “all remedies” language in another section about remedies:  Held: “[I]t is possible to harmonize and give effect to both provisions of the agreement. The ADR paragraph, in which the arbitration clause is found, controls the process of resolving disputes between the parties, while the remedies paragraph describes the substantive relief that may flow from decisions on those controversies.” No. 05-21-00639-CV (Feb. 1, 2023) (mem. op.).

Held: “[I]t is possible to harmonize and give effect to both provisions of the agreement. The ADR paragraph, in which the arbitration clause is found, controls the process of resolving disputes between the parties, while the remedies paragraph describes the substantive relief that may flow from decisions on those controversies.” No. 05-21-00639-CV (Feb. 1, 2023) (mem. op.).

The Stantons sued a construction contractor who did work on a commercial property near their home. The contractor sought to compel arbitration, arguing that their claim implicated an arbitration agreement in its contract with the relevant subcontractor. But the Stantons countered with evidence that the excavation work at issue was performed under a separate contract, directly with the property owners.

The Stantons sued a construction contractor who did work on a commercial property near their home. The contractor sought to compel arbitration, arguing that their claim implicated an arbitration agreement in its contract with the relevant subcontractor. But the Stantons countered with evidence that the excavation work at issue was performed under a separate contract, directly with the property owners.

The trial court denied the motion to compel arbitration. The Fifth Court affirmed. It noted the principle that “a bilateral agreement to arbitrate under the AAA rules constitutes clear and unmistakable evidence of the parties’ intent to delegate the issue of arbitrability to the arbitrator.” But that said, “[t]he subcontract between [the general] and [the sub] is not a bilateral contract with the Stantons.” Therefore, the trial court retained the authority to determine arbitrability. Scott + Reid General Contractors, Inc. v. Stanton, No. 05-22-00400-CV (Oct. 7, 2022) (mem. op.).

Reminding that the Family Code has some unique features not found in the more general Texas Arbitration Act, “which are expressly designed to avoid subjecting parties in divorce cases to arbitration when the contract containing the agreement to arbitrate is invalid or unenforceable,” the Texas Supreme Court held in In re Ayad that “[t]o comply with these statutes, a trial court must: (1) try the issue by giving each party an opportunity to be heard on all validity or enforceability challenges to the contract containing the arbitration clause, as well as an opportunity to offer evidence concerning any factual disputes or questions of foreign law material to the challenges; and (2) decide the challenges before ordering arbitration.” No. 22-0078 (Sept. 23, 2022) (per curiam).

The agreement at issue was an “Islamic Pre-Nuptial Agreement,” but the Court’s ruling did not require it to address any matters about the substance of that agreement.

The well-known poem Antigonish begins:

Yesterday, upon the stair,

I met a man who wasn’t there

He wasn’t there again today

I wish, I wish he’d go away.

In that general spirit, in recent days, both the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit and the Court of Appeals for the Fifth District at Dallas had close en banc votes involving questions of arbitrability, as to a party who “wasn’t there”–who had not signed an arbitration agreement, but was nevertheless potentially subject to it. (The Dallas case is discussed here; the Fifth Circuit’s, here.)

Whether the timing is an example of synchronicity I will leave to others. The courts’ difficulty with these issues shows the strong feelings provoked by the issue of court access, even among very sophisticated jurists, in an area of the law with well-developed case law on many key points.

The en banc Fifth Court divided 7-6 on a difficult arbitration issue; specifically, whether a court or the AAA should resolve arbitrability as to wrongful-death claims brought by estate representatives. Agreeing with the panel majority, the full-court majority saw it as an issue for the AAA; the dissent, one for court. A concurrence urged consistency with applicable federal law. Prestonwood Tradition, LP v. Jennings, Nos. 05-20-00380 and -00387 et seq. (Aug. 5, 2022).

The en banc Fifth Court divided 7-6 on a difficult arbitration issue; specifically, whether a court or the AAA should resolve arbitrability as to wrongful-death claims brought by estate representatives. Agreeing with the panel majority, the full-court majority saw it as an issue for the AAA; the dissent, one for court. A concurrence urged consistency with applicable federal law. Prestonwood Tradition, LP v. Jennings, Nos. 05-20-00380 and -00387 et seq. (Aug. 5, 2022).

Justice Pedersen wrote the majority opinion, joined by Justices Myers, Schenck (who wrote a concurring opinion), Osborne, Reichek, Goldstein, and Smith. Justice Partida-Kipness wrote the dissent, joined by Chief Justice Burns and Justices Molberg, Nowell, Carlyle, and Garcia. The panel consisted of Justices Pedersen and Goldstein in the majority and Justice Partida-Kipness in dissent.

Important arbitration-waiver case earlier this week from SCOTUS:

Important arbitration-waiver case earlier this week from SCOTUS:

“Most Courts of Appeals have answered that question by applying a rule of waiver specific to the arbitration context. Usually, a federal court deciding whether a litigant has waived a right does not ask if its actions caused harm. But when the right concerns arbitration, courts have held, a finding of harm is essential: A party can waive its arbitration right by litigating only when its conduct has prejudiced the other side. That special rule, the courts say, derives from the FAA’s ‘policy favoring arbitration.’ We granted certiorari to decide whether the FAA authorizes federal courts to create such an arbitration-specific procedural rule. We hold it does not.”

Morgan v. Sundance Inc., No. 21-328 (May 23, 2022).

After a split decision from the Fifth Court declined to send a personal-injury case to arbitration, the Texas Supreme Court ruled otherwise in Baby Dolls v. Sotero: “The Family’s argument, and the court of appeals’ holding, that Hernandez and the Club never had a meeting of the minds on the contract blinks the reality that they operated under it for almost two years, week after week, before Hernandez’s tragic death. We hold that the parties formed the agreement reflected in the contract they signed.” No. 20-0782 (Tex. March 18, 2022).

After a split decision from the Fifth Court declined to send a personal-injury case to arbitration, the Texas Supreme Court ruled otherwise in Baby Dolls v. Sotero: “The Family’s argument, and the court of appeals’ holding, that Hernandez and the Club never had a meeting of the minds on the contract blinks the reality that they operated under it for almost two years, week after week, before Hernandez’s tragic death. We hold that the parties formed the agreement reflected in the contract they signed.” No. 20-0782 (Tex. March 18, 2022).

The standard for waiver of a contractual arbitration right can be demanding, especially if the record does not contain all referenced material:

“Mary’s response to appellants’ amended motion to compel arbitration stated that appellants served responses to discovery in December 2016 and sent discovery requests of their own in February 2017. Appellants contend that the discovery they propounded was minimal, consisting of nine interrogatories, nine requests for admission, and one request for production. As no party attached any of the requests or responses to their filings in connection with the motions to compel arbitration, we cannot weigh any of the discovery-related factors in favor of or against waiver. Mary has not shown that the discovery in question was extensive, related to the merits of her claims, or would be unavailable in arbitration.”

Haddington Fund v. Kidwell, No. 05-19-01202 (Jan. 11, 2022) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

The majority opinion in Prestonwood Tradition, LP v. Jennings, No. 05-20-00380-CV et seq. (Oct. 22, 2021).concluded that wrongful-death and survival claims were controlled by the decedents’ arbitration agreements, including their delegation of arbitrability to the arbitrator. A dissent saw matters differently, citing Roe v. Ladymon, 318 S.W.3d 502 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2010, no pet.)).

Even on a court that has strong differences of opinion about the law that defines the boundary between the judicial process and arbitration, some questions command consensus–in Holifield v. Barclay Properties, Ltd., the Fifth Court agreed that “a bilateral agreement to arbitrate under the AAA rules constitutes clear and unmistakable evidence of the parties’ intent to delegate the issue of arbitrability to the arbitrator.” No. 05-21-00239-CV (Oct. 5, 2021) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

“The preservation requirements of appellate rule 33.1 apply to arbitrations.” And just as in a traditional litigation setting, the lack of a record created preservation problems in Alia Realty LLC v. Alhalwani: “In addition to a silent record as to whether appellees informed the arbitrator that the extended time to file a supplemental expert report was insufficient before proceeding to arbitration, appellees failed to make any such complaints in two postarbitration briefs. Instead, they argued the evidence was insufficient to support the arbitration award because appellants’ expert’s opinions were unsupported speculation, and their expert, unlike appellant’s expert, used the proper accounting analysis by reconciling bank accounts.” No. 05-21-00265-CV (Sept. 23, 2021) (mem. op.).

The successful party in an arbitration obtained confirmation of the award before the trial court ruled on the other party’s special appearance. The Fifth Court reversed, citing TRCP 84 and 120a as well as its own precedent: “Jayco was entitled to have its special appearance adjudicated prior to any decision on the merits. The rules of civil procedure give a trial court no discretion to hear a plea or pleading, including a motion to confirm an arbitration award, before hearing and determining a special appearance.” Jayco Hawaii LLC v. Viva Railings, LLC, No. 05-20-00528-CV (Aug. 25, 2021) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

The successful party in an arbitration obtained confirmation of the award before the trial court ruled on the other party’s special appearance. The Fifth Court reversed, citing TRCP 84 and 120a as well as its own precedent: “Jayco was entitled to have its special appearance adjudicated prior to any decision on the merits. The rules of civil procedure give a trial court no discretion to hear a plea or pleading, including a motion to confirm an arbitration award, before hearing and determining a special appearance.” Jayco Hawaii LLC v. Viva Railings, LLC, No. 05-20-00528-CV (Aug. 25, 2021) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

In an 8-1 decision, the Texas Supreme Court reversed the Fifth Court’s judgment in Fifth Court’s judgment in Aerotek v. Boyd, a dispute about whether employees agreed to arbitration via their employer’s electronic system. The court observed:

“It may be that the use of electronic contracts already exceeds the use of paper contracts or that it will soon. The [Texas Uniform Electronic Transactions Act] does not limit the ways in which electronic contracts may be proved valid, but it specifically states that proof of the efficacy of the security procedures used in generating a contract can prove that an electronic signature is attributable to an alleged signatory. An opposing party may, of course, offer evidence that security procedures lack integrity or effectiveness and therefore cannot reliably be used to connect a computer record to a particular person. But that attribution cannot be cast into doubt merely by denying the result that reliable procedures generate.”

(footnote omitted). A dissent would have evaluated the record differently. No. 20-0290 (Tex. May 28, 2021).

The parties in Ninety Nine Physician Services, PLLC v. Murray arbitrate d a business dispute; the lingering issue at confirmation was an award of $341,680 in attorneys’ fees. The Fifth Court found that the award was proper, reasoning as follows:

d a business dispute; the lingering issue at confirmation was an award of $341,680 in attorneys’ fees. The Fifth Court found that the award was proper, reasoning as follows:

- “[U]nder the parties’ distinct agreement and incorporation of the AAA rules, there were three circumstances in which the arbitrator was vested with the authority to award attorney’s fees (1) if all parties requested such an award or (2) if it was separately authorized by law or (3) if it is authorized by the arbitration agreement.” (emphasis in original); and then

- “Both parties submitted posthearing briefs in which they requested attorney’s fees. In their briefing, Appellees urged, as they do here, there was no basis in the general law to award fees to Appellant. … Appellees contend Appellant’s post-hearing brief is not a proper request for attorney’s fees. The arbitrator in interpreting the Commercial Rules evidently disagreed with Appellees and found the post-hearing briefs to be requests for attorney’s fees under Rule 47(d)(ii).”

The Court thus reversed a trial-court ruling that vacated that portion of the award. A concurrence would have reached the same result for a different reason: “Because appellant did not file any pleading affirmatively seeking attorneys’ fees until after the arbitration hearing, the arbitrator abused his discretion in awarding attorneys’ fees to appellant. The arbitrator’s mistake of law, however, is not grounds to vacate the award, and the trial court erred in doing so. Consequently, appellant was entitled to enforcement of the attorneys’ fees award but not on the basis relied upon by the majority.” No. 05-19-01216-CV (Feb. 22, 2021) (mem. op.).

The movants in GN Ventures v. Stanley won their argument that the TCPA applied to a motion in a dispute about arbitrability: “[E]ven though a request for a pre-arbitration temporary restraining order and temporary injunction merely seeks equitable remedies, and is not an independent cause of action, such a request is a ‘filing that requests . . . equitable relief’ and, therefore, a ‘legal action’ as defined by section 27.001(6). And because in this case, there is no underlying cause of action and appellants’ TCPA motion solely sought dismissal of the request for temporary restraining order and temporary injunction, that requested injunctive relief is the ‘claim’ the elements of which the Stanley affiliates must demonstrate a prima facie case by clear and specific evidence in the second step of the TCPA analysis we discuss below.” (citations omitted). Despite that win, however, they lost their motion because the nonmovants established a prima facie case for their requested injunctive relief. No. 05-19-01076-CV (Oct. 2, 2020).

The movants in GN Ventures v. Stanley won their argument that the TCPA applied to a motion in a dispute about arbitrability: “[E]ven though a request for a pre-arbitration temporary restraining order and temporary injunction merely seeks equitable remedies, and is not an independent cause of action, such a request is a ‘filing that requests . . . equitable relief’ and, therefore, a ‘legal action’ as defined by section 27.001(6). And because in this case, there is no underlying cause of action and appellants’ TCPA motion solely sought dismissal of the request for temporary restraining order and temporary injunction, that requested injunctive relief is the ‘claim’ the elements of which the Stanley affiliates must demonstrate a prima facie case by clear and specific evidence in the second step of the TCPA analysis we discuss below.” (citations omitted). Despite that win, however, they lost their motion because the nonmovants established a prima facie case for their requested injunctive relief. No. 05-19-01076-CV (Oct. 2, 2020).

If arguing that the plaintiff’s pleadings judicially admit arbitrability, be sure the record all lines up: “[T[]o the extent WorldVentures seeks to rely on a ‘judicial admission’ that TTF ‘consented to the 2019 agreements,’ the record does not show that the section 7.1 quoted in TTF’s petition necessarily came from the 2019 documents. The petition is silent as to what version of WorldVentures’ Policies & Procedures the quotation is from. Although the quoted section does not appear in the 2011 version, there were at least six additional versions in effect between 2012 and 2019. The record includes only the arbitration provision portions of those documents and does not show whether the quoted section 7.1 was unique to the 2019 version. Thus, the petition does not contain a ‘clear, deliberate, and unequivocal” statement of fact regarding consent to the 2019 agreements.'” WorldVentures Marketing v. Travel to Freedom, No. 05-20-00169-CV (Sept. 23, 2020) (mem. op.).

If arguing that the plaintiff’s pleadings judicially admit arbitrability, be sure the record all lines up: “[T[]o the extent WorldVentures seeks to rely on a ‘judicial admission’ that TTF ‘consented to the 2019 agreements,’ the record does not show that the section 7.1 quoted in TTF’s petition necessarily came from the 2019 documents. The petition is silent as to what version of WorldVentures’ Policies & Procedures the quotation is from. Although the quoted section does not appear in the 2011 version, there were at least six additional versions in effect between 2012 and 2019. The record includes only the arbitration provision portions of those documents and does not show whether the quoted section 7.1 was unique to the 2019 version. Thus, the petition does not contain a ‘clear, deliberate, and unequivocal” statement of fact regarding consent to the 2019 agreements.'” WorldVentures Marketing v. Travel to Freedom, No. 05-20-00169-CV (Sept. 23, 2020) (mem. op.).

The trial court did not abuse its discretion in finding an arbitration agreement procedurally unconscionable when: “Herman testified in his affidavits that the meeting with appellant [law firm]’s employee was less than ten minutes. Herman made a brief statement to the employee explaining the accident, and the employee told Herman to sign a document. Herman asked the employee if the document was a contract, and the employee answered, ‘No, we are just gathering information,’ that the Daspit firm would review the facts, and that a lawyer would call him. The employee was ‘very impatient’ and told Herman ‘he could not stay to explain things.’ Herman also testified that when he signed the document, he ‘did not understand . . . that it contained an arbitration clause.’ Herman argues appellant’s employee did not permit Herman to read the arbitration provision before signing the document.” Daspit Law Firm v. Herman, No. 05-19-00615-CV (Aug. 25, 2020) (mem. op.)

The trial court did not abuse its discretion in finding an arbitration agreement procedurally unconscionable when: “Herman testified in his affidavits that the meeting with appellant [law firm]’s employee was less than ten minutes. Herman made a brief statement to the employee explaining the accident, and the employee told Herman to sign a document. Herman asked the employee if the document was a contract, and the employee answered, ‘No, we are just gathering information,’ that the Daspit firm would review the facts, and that a lawyer would call him. The employee was ‘very impatient’ and told Herman ‘he could not stay to explain things.’ Herman also testified that when he signed the document, he ‘did not understand . . . that it contained an arbitration clause.’ Herman argues appellant’s employee did not permit Herman to read the arbitration provision before signing the document.” Daspit Law Firm v. Herman, No. 05-19-00615-CV (Aug. 25, 2020) (mem. op.)

After an earlier dispute about the merits of an interlocutory stay, the Fifth Court reached the substantive issue of arbitrability in Baby Dolls v. Sotero, a personal-injury lawsuit about a serious car accident involving two dancers after they left work. The key question was the interplay of the terms “License” and “Agreement” in the relevant contract; the panel majority concluded: “On this record, we conclude the trial court could have properly determined the parties’ minds could not have met regarding the contract’s subject matter and all its essential terms such that the contract is not an enforceable agreement. Consequently, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by denying the motions to compel arbitration.” (citations omitted). A dissent disputed whether that conclusion was a proper legal basis to deny a motion to compel arbitration, and would have reached a different result about the construction of the parties’ contract. No. 05-19-01443-CV (Aug. 21, 2020) (mem. op.)

After an earlier dispute about the merits of an interlocutory stay, the Fifth Court reached the substantive issue of arbitrability in Baby Dolls v. Sotero, a personal-injury lawsuit about a serious car accident involving two dancers after they left work. The key question was the interplay of the terms “License” and “Agreement” in the relevant contract; the panel majority concluded: “On this record, we conclude the trial court could have properly determined the parties’ minds could not have met regarding the contract’s subject matter and all its essential terms such that the contract is not an enforceable agreement. Consequently, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by denying the motions to compel arbitration.” (citations omitted). A dissent disputed whether that conclusion was a proper legal basis to deny a motion to compel arbitration, and would have reached a different result about the construction of the parties’ contract. No. 05-19-01443-CV (Aug. 21, 2020) (mem. op.)

Sometimes to state the issue is to decide it. For example, the Fifth Court’s opinion in Ruff v. Ruff began: “A pivotal question we address is whether a party can initiate an arbitration proceeding pursuant to a specific arbitration agreement, demand that a signatory to that agreement be compelled to participate in that arbitration, and then disavow the resulting award by alleging that he (the initiating party) did not agree to arbitrate according to that arbitration agreement.” The Court answered that question “no,” reviewing the invited-error and several estoppel doctrines. No. 05-18-00326-CV (Aug. 11, 2020).

Sometimes to state the issue is to decide it. For example, the Fifth Court’s opinion in Ruff v. Ruff began: “A pivotal question we address is whether a party can initiate an arbitration proceeding pursuant to a specific arbitration agreement, demand that a signatory to that agreement be compelled to participate in that arbitration, and then disavow the resulting award by alleging that he (the initiating party) did not agree to arbitrate according to that arbitration agreement.” The Court answered that question “no,” reviewing the invited-error and several estoppel doctrines. No. 05-18-00326-CV (Aug. 11, 2020).

Lunch-buying did not create arbitrator bias in Texas Health Management v. Healthspring: “THM next claims the Tribunal was partial because it received free beverages and meals from Healthspring every day of the hearing. THM claims it received this information from a Decem

Lunch-buying did not create arbitrator bias in Texas Health Management v. Healthspring: “THM next claims the Tribunal was partial because it received free beverages and meals from Healthspring every day of the hearing. THM claims it received this information from a Decem ber 5, 2017 letter from Healthspring to the Tribunal. However, on the first day of arbitration, Appel acknowledged, “I understand, Mr. Leckerman, you ordered in lunch.” Leckerman, Healthspring’s attorney, confirmed lunch would arrive around noon. THM did not question or object to Healthspring providing lunch.” (footnote omitted).

ber 5, 2017 letter from Healthspring to the Tribunal. However, on the first day of arbitration, Appel acknowledged, “I understand, Mr. Leckerman, you ordered in lunch.” Leckerman, Healthspring’s attorney, confirmed lunch would arrive around noon. THM did not question or object to Healthspring providing lunch.” (footnote omitted).

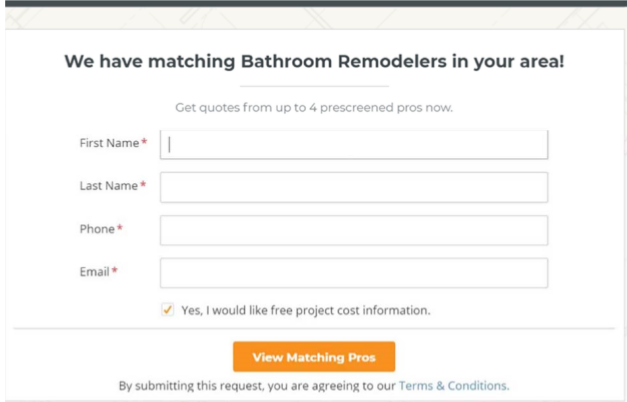

The philosophy of aesthetics finds practical application in the law of website user agreements, as illustrated in Home Advisor, Inc. v. Waddell. The plaintiffs sought to avoid arbitration of their claims, arguing that the notice about “terms and conditions” on this screen was not sufficiently conspicuous:

The Fifth Court disagreed. Citing the recent Northern District of Texas opinion in Phillips v. Neutron Holdings, the Court noted a distinction among “clickwrap” agreements, “browsewrap” agreements, and “sign-in-wrap” agreements. This case involved a sign-in wrap agreement, which “notifies the user of the existence of the website’s terms and conditions and advises the user that he or she is agreeing to the terms when registering an account or signing up,” and is “typically enforce[d] . . . when notice of the existence of the te rms was ‘reasonably conspicuous.'” The Court found that this agreement was conspicuous enough, noting that “more cluttered and complicated sign-in-wrap screens have been found to provide sufficient notice” of similar contract terms. No. 05-19-00669-CV (June 4, 2020) (mem. op.)

rms was ‘reasonably conspicuous.'” The Court found that this agreement was conspicuous enough, noting that “more cluttered and complicated sign-in-wrap screens have been found to provide sufficient notice” of similar contract terms. No. 05-19-00669-CV (June 4, 2020) (mem. op.)

Alcala sought to avoid arbitration of a premises-liability claim against her employer, arguing, inter alia, that she did not understand English. Her argument did not prevail because of direct-benefits estoppel:

Alcala sought to avoid arbitration of a premises-liability claim against her employer, arguing, inter alia, that she did not understand English. Her argument did not prevail because of direct-benefits estoppel:

‘The record reflects Alcala received $5,116.46 under the Plan in the form of benefits paid to cover medical expenses related to the subject of her suit against appellants: her February 2016 on-the-job injury. The Plan itself provided, “there is an Arbitration Policy attached to the back of this booklet.” The Agreement provided, “Payments made under [the] Plan . . . constitute consideration for this Agreement.” Having obtained the benefits under the Plan, which incorporates the Agreement by reference, Alcala cannot legally or equitably object to the arbitration provision in the Agreement.’

Multipacking Solutions v. Alcala, No. 05-19-00303-CV (April 14, 2020).

The appellants in Trubenbach v. Energy Exploration “urge[d] that ‘context matters.’ They argue that as non-signatories, they can compel Energy Exploration to arbitration but Energy Exploration cannot compel them to arbitration. But this is not a case in which non-signatories first moved to compel arbitration, then later changed their minds, withdrew their consent, and proceeded with the litigation in a judicial forum. Here, appellants urged diametrically opposing positions in two different courts at the same time.” (emphasis in original).

The appellants in Trubenbach v. Energy Exploration “urge[d] that ‘context matters.’ They argue that as non-signatories, they can compel Energy Exploration to arbitration but Energy Exploration cannot compel them to arbitration. But this is not a case in which non-signatories first moved to compel arbitration, then later changed their minds, withdrew their consent, and proceeded with the litigation in a judicial forum. Here, appellants urged diametrically opposing positions in two different courts at the same time.” (emphasis in original).

As a result, “[t]heir conduct in claiming rights under the arbitration agreement and their conduct throughout the course of this proceeding clearly reflected their willingness to forego their right to a judicial forum.” No. 05-18-01090-CV (March 27, 2020) (mem. op.). The Court also observed: “Appellants’ actions are akin to behavior prohibited by the invited error doctrine—a party may not complain of an error which the party invited.” (citations omitted).

In a dispute about arbitrability, the plaintiff claimed never to have seen the arbitration agreement, and after receiving evidence about the defendant’s computer system, the trial judge agreed.

In a dispute about arbitrability, the plaintiff claimed never to have seen the arbitration agreement, and after receiving evidence about the defendant’s computer system, the trial judge agreed.

A panel majority affirmed the denial of the motion to compel arbitration: “Aerotek made the choice to forego in-person wet-ink signatures on paper contracts. This may be a good business decision that allows it to more efficiently process more business than otherwise possible. And in this case, Aerotek made the choice to bring only one person, an employee without apparent IT experience specific to the type of computer system whose technical reliability and security she sought to vouch for. Aerotek did this in the face of admitting it had contracted out creation and implementation of this system to another entity altogether and brought no witness from that entity. We conclude Aerotek did not present evidence establishing the opposite of a vital fact, here that appellees’ denials of ever seeing the a rbitration contracts were physically impossible given Aerotek’s computer system.”

rbitration contracts were physically impossible given Aerotek’s computer system.”

A dissent had a different view of the evidence and warned that as a policy matter: “This would allow any party to a contract signed electronically to deny the existence of the contract even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the contract was signed. Further, this holding amounts to a state rule discriminating on its face against arbitration, which is expressly prohibited.”

The en banc court denied review in a brief order (Justices Molberg (the trial judge) and Whitehill did not participate); a dissent by Justice Schenck reiterated the dissent’s warnings and “urge[d] prompt review by the Texas Supreme Court.” (joined by Justices Bridges (the panel dissenter), Evans, and Myers).

Section 171.025 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code says: “The court shall stay a proceeding that involves an issue subject to arbitration if an order for arbitration or an application for that order is made under this subchapter.” The dispute in In re: Baby Dolls Topless Saloon involved a mandamus petition from a defendant’s perceived inability to obtain an order implementing this stay, during its interlocutory appeal from denial of its motion to compel arbitration.

Section 171.025 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code says: “The court shall stay a proceeding that involves an issue subject to arbitration if an order for arbitration or an application for that order is made under this subchapter.” The dispute in In re: Baby Dolls Topless Saloon involved a mandamus petition from a defendant’s perceived inability to obtain an order implementing this stay, during its interlocutory appeal from denial of its motion to compel arbitration.

The panel majority denied the petition, finding that the issue of arbitrability “has been briefed in the interlocutory appeal and will be decided by the panel of justices assigned to decide that appeal, which is just as the legislature intended when it enacted section 51.016 and provided for an interlocutory appeal of an order denying a motion to compel arbitration. Because we follow the rule of law, we, as one panel of this Court, will not depart from this Court’s prior holding that mandamus will not issue when the legislature has expressly provided an adequate remedy by appeal.”

A dissent would have granted a stay as part of resolution of the mandamus petition, noting: “While our own statute and rules appear to compel the same result by dictating a stay of the overlapping proceedings of whatever court is first asked, we have not done so here. Accordingly, relator has properly brought the issue before us for mandamus relief that should be available under long recognized mandamus standards and without the need of further machination or a fifth request for stay.” No. 05-20-00015-CV (Feb. 24, 2020) (mem. op.)

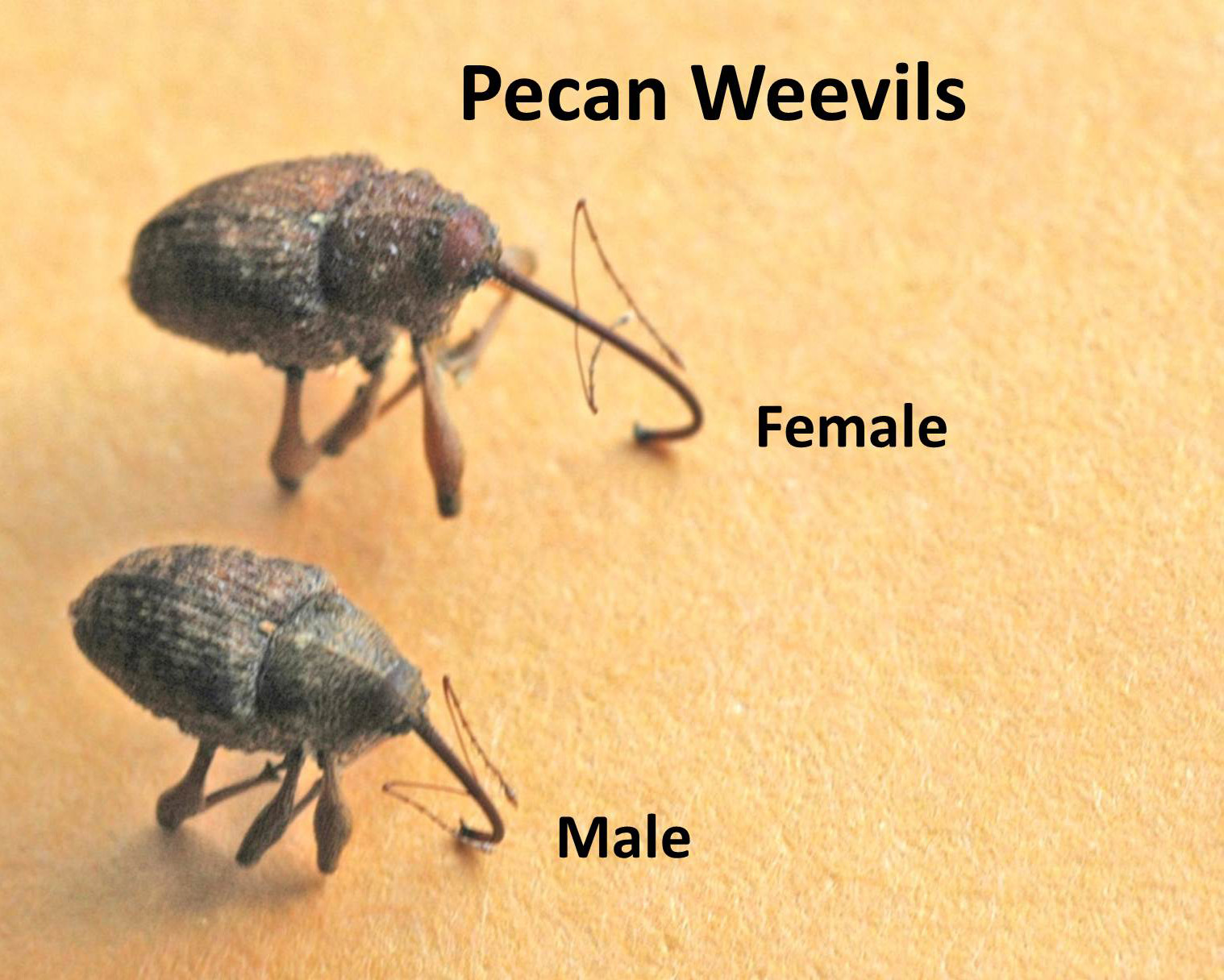

In an unusually nutty case, the parties’ arbitration clause provided:

In an unusually nutty case, the parties’ arbitration clause provided:

All disputes, claims, or controversies arising out of or relating to this Agreement, or the breach thereof, except as to the quality of the product delivered, shall be settled solely by arbitration held in Dallas, Texas, in accordance with the rules then obtaining of the American Arbitration Association, and judgment upon any award may be entered in any court having jurisdiction thereof.

(emphasis added). The plaintiff’s allegations “[a]ll . . . concern whether the pecan pieces San Saba sold contained pecan weevil larvae so that they were not merchantable and were unfit for human consumption” – in other words, claims about “the quality of the produce delivered” within the meaning of the above carveout. The Fifth Court thus affirmed the trial court’s denial of a motion to compel arbitration. San Saba Pecan LP v. Give & Go Prepared Foods Corp., No. 05-19-00214-CV (Dec. 6, 2019) (mem. op.)

Ward sued Gray, alleging that “Gray forced Ward’s resignation to preclude the Partnership’s obligation to purchase Ward’s [partnership] interest. . . . In addition, Ward alleges that [the general partner] made defamatory statements about his employment status when Partnership employees were told that Ward resigned.”

Ward sued Gray, alleging that “Gray forced Ward’s resignation to preclude the Partnership’s obligation to purchase Ward’s [partnership] interest. . . . In addition, Ward alleges that [the general partner] made defamatory statements about his employment status when Partnership employees were told that Ward resigned.”

The relevant limited-partnership agreement, signed by both Gray and Ward, said: “All disputes and claims relating to this Agreement, the rights and obligations of the parties hereto, or any claims or causes of action relating to the performance of either party that have not been settled through mediation will be settled by arbitration.”

The Gray v. Ward majority found that all of Ward’s claims were subject to arbitration: “As Ward’s petition demonstrates, the factual allegations supporting his contract and fiduciary duty breach claims are intertwined with the LP Agreement and Ward’s wrongful termination and defamation claims. Indeed, the only way the statement about Ward’s resignation could be defamatory is in the context of the limited partnership’s operation. The LP Agreement controls the terms of the buy-out from which the entire dispute arises. Under these circumstances, we cannot conclude that Ward’s wrongful termination and defamation claims are completely independent of and can be maintained without reference to the LP Agreement.”

A dissent reasoned: “Ward’s employment-related claims have no significant relationship to the limited partnership agreement, and . . . the arbitration agreement here applies only to Ward’s role as a limited partner . . . , and not to his distinct role as an employee,” and concluded: “This is yet another case in which arbitration becomes a matter of coercion, not consent, with the right to trial by jury as the recurrent fatality.”

A dissent reasoned: “Ward’s employment-related claims have no significant relationship to the limited partnership agreement, and . . . the arbitration agreement here applies only to Ward’s role as a limited partner . . . , and not to his distinct role as an employee,” and concluded: “This is yet another case in which arbitration becomes a matter of coercion, not consent, with the right to trial by jury as the recurrent fatality.”

No. 05-18-00266-CV (Aug. 9, 2019).

The recent case of SIG-TX Assets v. Serrato, over a dissent, declined to require arbitration of nonsignatories’ claims about mishandled funeral services. It would be wrong to read too much into that case, in light of Meritage Homes v. Mudda, which required nonsignatories to arbitrate claims about a home’s construction: “Here, we are presented with facts requiring application of the exception because the Muddas are seeking benefits under the Limited Warranty while simultaneously attempting to avoid its arbitration provision.” No. 05-18-00934-CV (July 3, 2019) (unpublished).

The recent case of SIG-TX Assets v. Serrato, over a dissent, declined to require arbitration of nonsignatories’ claims about mishandled funeral services. It would be wrong to read too much into that case, in light of Meritage Homes v. Mudda, which required nonsignatories to arbitrate claims about a home’s construction: “Here, we are presented with facts requiring application of the exception because the Muddas are seeking benefits under the Limited Warranty while simultaneously attempting to avoid its arbitration provision.” No. 05-18-00934-CV (July 3, 2019) (unpublished).

In a macabre echo of the old English case about the two ships Peerless, in SIG-TX Assets, LLC v. Serrato, Serrato family members accused a funeral home of confusing the bodies of two women named Maria. The funeral home sought to compel arbitration under a theory of direct-benefits estoppel, and the panel majority disagreed: “[A]though SIG-TX’s duty to prepare and inter Maria’s body arose from the contracts, there is an independent duty under Texas tort law to immediate family members not to negligently mishandle a corpse.” A dissent saw the family-members’ claims as directly analogous to those of the nonsignatory to the construction contract in In re: Weekley Homes, 180 S.W.3d 127 (Tex. 2005). No. 05-18-00462-CV (April 23, 2019) (mem. op.) (Partida-Kipness, J., for the majority, joined by Carlyle, J.; Bridges, J., dissenting).

In a macabre echo of the old English case about the two ships Peerless, in SIG-TX Assets, LLC v. Serrato, Serrato family members accused a funeral home of confusing the bodies of two women named Maria. The funeral home sought to compel arbitration under a theory of direct-benefits estoppel, and the panel majority disagreed: “[A]though SIG-TX’s duty to prepare and inter Maria’s body arose from the contracts, there is an independent duty under Texas tort law to immediate family members not to negligently mishandle a corpse.” A dissent saw the family-members’ claims as directly analogous to those of the nonsignatory to the construction contract in In re: Weekley Homes, 180 S.W.3d 127 (Tex. 2005). No. 05-18-00462-CV (April 23, 2019) (mem. op.) (Partida-Kipness, J., for the majority, joined by Carlyle, J.; Bridges, J., dissenting).

AMX brought an arbitration against an architect; the architect moved to dismiss because AMX did not obtain a certificate of merit, and when that motion was unsuccessful sought appellate review. The Fifth Court, noting that this was an issue of first impression, concluded that “the right to interlocutory appeal granted by section 150.002 does not apply to an order rendered by an arbitration panel, and the Texas Arbitration Act (TAA) does not provide a means for judicial review of such an order . . . .” Accordingly, it vacated the trial court’s order of dismissal as void and dismissed the appeal for lack of jurisdiction. SM Architects v. AMX Veteran Specialty Services, 05-17-01064-CV (Nov. 9, 2018).

AMX brought an arbitration against an architect; the architect moved to dismiss because AMX did not obtain a certificate of merit, and when that motion was unsuccessful sought appellate review. The Fifth Court, noting that this was an issue of first impression, concluded that “the right to interlocutory appeal granted by section 150.002 does not apply to an order rendered by an arbitration panel, and the Texas Arbitration Act (TAA) does not provide a means for judicial review of such an order . . . .” Accordingly, it vacated the trial court’s order of dismissal as void and dismissed the appeal for lack of jurisdiction. SM Architects v. AMX Veteran Specialty Services, 05-17-01064-CV (Nov. 9, 2018).

The appellant in CBRE, Inc. v. Turner sought to avoid arbitration based on a long line of Texas authority about “illusory” arbitration clauses, see, e.g., In re: Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d 566 (Tex. 2002). This clause, however, “unlike the employment agreements in other cases . . . did not give CBRE the right to modify the employment agreement unilaterally or the right to terminate the arbitration policy without terminating the employment agreement,” and thus was not illusory. No. 05-18-00404-CV (Oct. 22, 2018).

The appellant in CBRE, Inc. v. Turner sought to avoid arbitration based on a long line of Texas authority about “illusory” arbitration clauses, see, e.g., In re: Halliburton Co., 80 S.W.3d 566 (Tex. 2002). This clause, however, “unlike the employment agreements in other cases . . . did not give CBRE the right to modify the employment agreement unilaterally or the right to terminate the arbitration policy without terminating the employment agreement,” and thus was not illusory. No. 05-18-00404-CV (Oct. 22, 2018).

The party opposing arbitration in Camp v. Potts pointed to a year-long delay in moving to compel arbitration, during which the underlying matter was set for trial and required travel and expense to be available during that setting. Unfortunately, as to other parts of the framework in Perry Homes v. Cull, 258 S.W.3d 580 (Tex. 2008), “[t]he record . . . contains no evidence the trial preparation would not be useful in arbitrating their claims as well,” and the parties “have not argued, and we see no evidence in the record, that the delay caused any harm caused to their legal position.” Accordingly, the Fifth Court reversed the denial of the motion to compel arbitration. No. 05-18-00149-CV (Oct. 1, 2018) (mem. op.)

The party opposing arbitration in Camp v. Potts pointed to a year-long delay in moving to compel arbitration, during which the underlying matter was set for trial and required travel and expense to be available during that setting. Unfortunately, as to other parts of the framework in Perry Homes v. Cull, 258 S.W.3d 580 (Tex. 2008), “[t]he record . . . contains no evidence the trial preparation would not be useful in arbitrating their claims as well,” and the parties “have not argued, and we see no evidence in the record, that the delay caused any harm caused to their legal position.” Accordingly, the Fifth Court reversed the denial of the motion to compel arbitration. No. 05-18-00149-CV (Oct. 1, 2018) (mem. op.)

The third prong of the Craddock test for setting aside a default judgment – that the defendant “file the motion at a time when granting it will occasion no delay or otherwise work an injury to the plaintiff” – is commonly cited when awarding attorneys’ fees to the plaintiff. The plaintiff in In re: CGI Construction went a step further and also obtained a requirement that the defendant waive its contractual right to arbitrate. The Fifth Court conditionally granted mandamus relief, finding as a matter of law (in light of the strong policy favoring arbitration) that “the trial court may not condition the granting of a new trial and motion to set aside default judgment on waiver of contractual arbitration rights,” and that the plaintiff did not otherwise establish evidence of injury (a lost witness, etc.) if arbitration proceeded. No. 05-18-00320-CV (June 18, 2018) (mem. op.)

The third prong of the Craddock test for setting aside a default judgment – that the defendant “file the motion at a time when granting it will occasion no delay or otherwise work an injury to the plaintiff” – is commonly cited when awarding attorneys’ fees to the plaintiff. The plaintiff in In re: CGI Construction went a step further and also obtained a requirement that the defendant waive its contractual right to arbitrate. The Fifth Court conditionally granted mandamus relief, finding as a matter of law (in light of the strong policy favoring arbitration) that “the trial court may not condition the granting of a new trial and motion to set aside default judgment on waiver of contractual arbitration rights,” and that the plaintiff did not otherwise establish evidence of injury (a lost witness, etc.) if arbitration proceeded. No. 05-18-00320-CV (June 18, 2018) (mem. op.)

Assuming arguendo – a considerable assumption given recent opinions on the point – that “manifest disregard of the law” is a viable challenge to an arbitration award, it did not apply even to a threshold issue such as standing when: “The parties agree that the arbitrator heard evidence and argument offered by both parties on the question of Sricom’s capacity to recover on its counterclaim. This evidence included Sricom’s certificate of authority to do business in Texas, the parties’ contract, and evidence of the parties’ alleged breaches and when those breaches occurred. The arbitrator’s acceptance of Sricom’s arguments and evidence instead of C Tekk’s, even if erroneous, was not manifest disregard of the law.” C Tekk Solutions, Inc. v. Sricom, Inc., No. 05-17-00845-CV (May 1, 2018) (mem. op.)

Assuming arguendo – a considerable assumption given recent opinions on the point – that “manifest disregard of the law” is a viable challenge to an arbitration award, it did not apply even to a threshold issue such as standing when: “The parties agree that the arbitrator heard evidence and argument offered by both parties on the question of Sricom’s capacity to recover on its counterclaim. This evidence included Sricom’s certificate of authority to do business in Texas, the parties’ contract, and evidence of the parties’ alleged breaches and when those breaches occurred. The arbitrator’s acceptance of Sricom’s arguments and evidence instead of C Tekk’s, even if erroneous, was not manifest disregard of the law.” C Tekk Solutions, Inc. v. Sricom, Inc., No. 05-17-00845-CV (May 1, 2018) (mem. op.)

A clean example of mootness appears in Tru Exploration LLC v. Energy Exploration I LLC: “The dispute on appeal centers on whether arbitration is required. Arbitration having been conducted and an award having been issued, the controversy no longer exists and the appeal is moot.” No. 05-15-00217-CV (April 27, 2018) (mem. op.) (applying Trulock v. City of Duncanville, 277 S.W.3d 920, 923 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2009, no pet.).

The parties’ arbitration clause said that, after a three-arbitrator panel was selected, the arbitrators “shall hold a hearing and make an award within sixty (60) days of the filing for arbitration.” The panel issued a “Partial Final Award” within sixty days and a complete award later; the trial court found the final award was untimely and declined to confirm it. The Fifth Court found that the agreement only required “an award,” not a final award, and that the arbitration panel had the last word on the issue because the parties had incorporated AAA ruled, which give “[t]he arbitrator . . . the power to rule on his or her own jurisdiction . . . ” Signature Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Ranbaxy, Inc., No. 05-17-00412-CV (March 12, 2018) (mem. op.)

The parties’ arbitration clause said that, after a three-arbitrator panel was selected, the arbitrators “shall hold a hearing and make an award within sixty (60) days of the filing for arbitration.” The panel issued a “Partial Final Award” within sixty days and a complete award later; the trial court found the final award was untimely and declined to confirm it. The Fifth Court found that the agreement only required “an award,” not a final award, and that the arbitration panel had the last word on the issue because the parties had incorporated AAA ruled, which give “[t]he arbitrator . . . the power to rule on his or her own jurisdiction . . . ” Signature Pharmaceuticals LLC v. Ranbaxy, Inc., No. 05-17-00412-CV (March 12, 2018) (mem. op.)

A defendant can rely on factual allegations to establish the proper forum, when the defendant will later strive to negate the merits of those same allegations. That idea was vividly illustrated in Buck’s Cabaret v. Lantrip, in which an entertainer at a Dallas club sued for her injuries in a car accident after leaving the premises, alleging that the club served her excessive alcohol. The Fifth Court reversed the denial of the club’s motion to compel arbitration under a provision in its agreement with the dancer that reached “ANY CONTROVERSY, DISPUTE, OR CLAIM … ARISING OUT OF THIS LEASE OR OUT OF ENTERTAINER PERFORMING AND/OR WORKING AT THE CLUB AT ANY TIME.” The Court noted:

The factual allegations giving rise to Lantrip’s claims are that Buck’s (1) sold her alcoholic beverages after it was apparent she was obviously intoxicated, and (2) required her to consume alcoholic beverages, a breach of Buck’s duty to use ordinary care in providing a reasonably safe workplace. Although Lantrip urges that she was a patron because Buck’s sold her alcoholic beverages, the fact that she purchased drinks is not necessarily inconsistent with her working under the terms of the Lease at the time. Indeed, Buck’s could not require Lantrip to purchase drinks if she was merely a patron.

The club will certainly dispute those allegations at the arbitration hearing, but for purposes of determining the forum, they proved dispositive.No. 05-17-00647-CV (Feb. 23, 2018) (mem. op.)

Craig moved to vacate an arbitration award: “Thus, under [Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code] section 171.094, she was required to arrange for service of process on appellees upon filing the motion. Craig did not arrange for service of process until she filed her supplemental motion to vacate on September 1, 2016, more than five months after the arbitration panel entered its award. Because she did not serve notice of her motion to vacate within [FAA] Section 12’s three-month limitations period, the service was untimely and the trial court was required to dismiss her motion as untimely.” The Fifth Court declined to apply any equitable tolling doctrine, and rejected an earlier emailing of the motion as inadequate under the TAA’s procedural requirements. Craig v. Southwest Securities, No. 05-16-01378-CV (Dec. 18, 2017) (mem. op.)

Craig moved to vacate an arbitration award: “Thus, under [Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code] section 171.094, she was required to arrange for service of process on appellees upon filing the motion. Craig did not arrange for service of process until she filed her supplemental motion to vacate on September 1, 2016, more than five months after the arbitration panel entered its award. Because she did not serve notice of her motion to vacate within [FAA] Section 12’s three-month limitations period, the service was untimely and the trial court was required to dismiss her motion as untimely.” The Fifth Court declined to apply any equitable tolling doctrine, and rejected an earlier emailing of the motion as inadequate under the TAA’s procedural requirements. Craig v. Southwest Securities, No. 05-16-01378-CV (Dec. 18, 2017) (mem. op.)

In FC Background LLC v. Fritze, the Fifth Court affirmed the trial court’s conclusion that a merger clause extinguished an arbitration clause in an earlier agreement between the parties. Distinguishing other cases on the general topic, the Court observed that those opinions involved a “subsequent agreement with the merger clause [that] expressly provided for the continued enforceability of prior agreements.” Here, however, the clause “does not contain the limiting language, ‘with respect to the subject matter hereof,’ and thenon-compete agreement incorporates by reference only the December 28 employment agreement but not the employment application that has the arbitration clause sought to be enforced. The merger clause here expressly supersedes any previous written or oral agreements between [the parties] relating to employment.” No. 05-17-00277-CV (Nov. 16, 2017) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original).

In FC Background LLC v. Fritze, the Fifth Court affirmed the trial court’s conclusion that a merger clause extinguished an arbitration clause in an earlier agreement between the parties. Distinguishing other cases on the general topic, the Court observed that those opinions involved a “subsequent agreement with the merger clause [that] expressly provided for the continued enforceability of prior agreements.” Here, however, the clause “does not contain the limiting language, ‘with respect to the subject matter hereof,’ and thenon-compete agreement incorporates by reference only the December 28 employment agreement but not the employment application that has the arbitration clause sought to be enforced. The merger clause here expressly supersedes any previous written or oral agreements between [the parties] relating to employment.” No. 05-17-00277-CV (Nov. 16, 2017) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original).

A challenge to AAA’s notice of hearing was rejected, and the award confirmed, in Heriage v. BNSF Logistics: “The record shows the AAA sent notice of the May 4th arbitration hearing to appellants on two occasions via both electronic and certified mail––one was approximately two months before the hearing; the other six days before the hearing. The written notices were sent to the physical address listed in the agreement, and the electronic notices were sent to an email address that Herriage admitted he conducted business from in the past but that he no longer bothered to check and had never closed.” 05-16-01232-CV (Nov. 17, 2017) (mem. op.)

A challenge to AAA’s notice of hearing was rejected, and the award confirmed, in Heriage v. BNSF Logistics: “The record shows the AAA sent notice of the May 4th arbitration hearing to appellants on two occasions via both electronic and certified mail––one was approximately two months before the hearing; the other six days before the hearing. The written notices were sent to the physical address listed in the agreement, and the electronic notices were sent to an email address that Herriage admitted he conducted business from in the past but that he no longer bothered to check and had never closed.” 05-16-01232-CV (Nov. 17, 2017) (mem. op.)

In an uncommon but fundamental challenge to an arbitration agreement, the plaintiff relied upon his inability to understand English. The Fifth Court rejected this challenge under general principles of contract formation:

“It is unusual that MiCocina translated the Mutual Agreement to Arbitrate, summary plan description, and handbook into Spanish, but not the one-page Acknowledgment form. However, on this record, there is no evidence of a fraudulent misrepresentation or trickery that would relieve Balderas of the consequences of failing to read or have read to him a document he voluntarily signed. In light of the obligation an illiterate party has to have a document read to them before they sign it and the lack of evidence of a fraudulent misrepresentation or trickery, we conclude Balderas is bound by his signature on the Acknowledgment. Accordingly, Balderas failed to prove procedural unconscionability and fraudulent inducement.”

MiCocina v. Balderas, No. 05-16-01507-CV (Oct. 27, 2017) (mem. op.) (citations omitted; distinguishing Delfingen US-Texas, LP v. Valenzuela, 407 S.W.3d 791

(Tex. App.—El Paso 2013, no pet.)).T

At issue in Galaxy Builers, Ltd. v. Globus Management Group was a trial court order denying enforcemement of an arbitrator’s subpoena. While the order said that it was

At issue in Galaxy Builers, Ltd. v. Globus Management Group was a trial court order denying enforcemement of an arbitrator’s subpoena. While the order said that it was  final, section 171.098 of the Texas Arbitration Act does not list it as an appealable category of arbitration-related ruling; thus, the appeal was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. No. 05-17-00831-CV (Oct. 2, 2017) (mem. op.)

final, section 171.098 of the Texas Arbitration Act does not list it as an appealable category of arbitration-related ruling; thus, the appeal was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. No. 05-17-00831-CV (Oct. 2, 2017) (mem. op.)

Among other holdings related to the arbitrability of a dispute between a business and a former employee, the Fifth Court rejected an argument that the defendant business had waived its right to invoke arbitration: “In short, many factors weigh against a waiver finding: (i) Tantrum is the defendant, not the plaintiff, (ii) Tantrum’s delay in seeking arbitration was not extreme, and Carson has not shown an improper reason for the delay, (iii) Tantrum did not seek a merits disposition of Carson’s claims, and it did not conduct an inordinate amount of discovery, (iv) Tantrum’s counterclaims are arguably compulsory counterclaims, (v) Carson did not show that the parties have spent an inordinate amount of time or money litigating this case, and (vi) Carson did not show that the discovery Tantrum conducted would have been unavailable in arbitration or would not be useful in the arbitration.” Tantrum Street LLC v. Carson, No. 05-16-01096-CV (July 24, 2017).

Among other holdings related to the arbitrability of a dispute between a business and a former employee, the Fifth Court rejected an argument that the defendant business had waived its right to invoke arbitration: “In short, many factors weigh against a waiver finding: (i) Tantrum is the defendant, not the plaintiff, (ii) Tantrum’s delay in seeking arbitration was not extreme, and Carson has not shown an improper reason for the delay, (iii) Tantrum did not seek a merits disposition of Carson’s claims, and it did not conduct an inordinate amount of discovery, (iv) Tantrum’s counterclaims are arguably compulsory counterclaims, (v) Carson did not show that the parties have spent an inordinate amount of time or money litigating this case, and (vi) Carson did not show that the discovery Tantrum conducted would have been unavailable in arbitration or would not be useful in the arbitration.” Tantrum Street LLC v. Carson, No. 05-16-01096-CV (July 24, 2017).

The arbitration clause in Employee Solutions v. Wilkerson said, in part, that it applied to “. . . any and all claims challenging the existence, validity or enforceability of this [agreement] (in whole or in part) or challenging the applicability of this [agreement] to a particular dispute or claim.” To get around this broad language, the party opposing arbitration contended that it did not reach a “purely procedural” matter – the alleged failure to serve a written demand for arbitration on him and file it with the arbitral authority within the statute of limitations for negligence. The Fifth Court disagreed, noting the parties’ dispute as to whether this matter was a condition precedent to arbitration, which brought it squarely within the above language. No. 05-16-00283-CV (May 10, 2017) (mem. op.)

Heath’s employment agreement incorporated a confidentiality agreement, which in turn required arbitration of “any controversy, dispute or claim arising out of or in any way related to or involving the interpretation, performance or breach of this Agreement . . .” The Fifth Court noted that phrases such as “any controversy” are viewed, by federal and state courts, as “broad arbitration clauses capable of expansive reach.” It rejected the argument that the term “this Agreement” referred only to the confidentiality agreement, even though that agreement had a merger clause, because the arbitration clause refers to both claims “arising out of” and “in any way related to” the agreement. The Court also noted that the employment and confidentiality agreement were executed at the same time, and that its holding would apply fully to Heath’s tort claims as well. Advocare GP LLC v. Heath, No. 05-16-0049-CV (Jan. 5, 2017) (mem. op.)

Heath’s employment agreement incorporated a confidentiality agreement, which in turn required arbitration of “any controversy, dispute or claim arising out of or in any way related to or involving the interpretation, performance or breach of this Agreement . . .” The Fifth Court noted that phrases such as “any controversy” are viewed, by federal and state courts, as “broad arbitration clauses capable of expansive reach.” It rejected the argument that the term “this Agreement” referred only to the confidentiality agreement, even though that agreement had a merger clause, because the arbitration clause refers to both claims “arising out of” and “in any way related to” the agreement. The Court also noted that the employment and confidentiality agreement were executed at the same time, and that its holding would apply fully to Heath’s tort claims as well. Advocare GP LLC v. Heath, No. 05-16-0049-CV (Jan. 5, 2017) (mem. op.)

In Heritage Numismatic Auctions v. Stiel, a dispute about the the sale of rare coins, the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a motion to compel arbitration, finding that the relevant documents were not adequately proved up by the sponsoring affidavit. The witness “did not testify that the documents in Exhibit F were ‘true and correct’ copies of the contracts or otherwise state that they were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals.” While the affidavit began with the phrase, “The facts contained herein are true and correct,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could interpret this statement as asserting the factual averments in the affidavit were true and correct but not asserting the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals as required by Rule 902(10)(B)(2).” Finally, from a general description of the documents as “the various Terms and Conditions . . . ,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could have concluded that [the witness’s] statement did not constitute testimony that the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact copies of the contracts.” No. 05-16-00299-CV (Dec. 16, 2016) (mem. op.)

In Heritage Numismatic Auctions v. Stiel, a dispute about the the sale of rare coins, the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a motion to compel arbitration, finding that the relevant documents were not adequately proved up by the sponsoring affidavit. The witness “did not testify that the documents in Exhibit F were ‘true and correct’ copies of the contracts or otherwise state that they were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals.” While the affidavit began with the phrase, “The facts contained herein are true and correct,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could interpret this statement as asserting the factual averments in the affidavit were true and correct but not asserting the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals as required by Rule 902(10)(B)(2).” Finally, from a general description of the documents as “the various Terms and Conditions . . . ,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could have concluded that [the witness’s] statement did not constitute testimony that the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact copies of the contracts.” No. 05-16-00299-CV (Dec. 16, 2016) (mem. op.)

In its order denying a mandamus petition in the case of In re: Adelphi Group, the Fifth Court reminds: “Although parties may expend time and money if they are ordered to arbitration improperly, delay and expense—standing alone—will not render the final appeal inadequate. Further, mandamus as a remedy for review of orders compelling arbitration should be limited to the comparatively rare cases where the legislature has through statute expressed a public policy that overrides the public policy favoring arbitration.” No. 05-16-01060-CV (Sept. 22, 2016) (mem. op.)

In its order denying a mandamus petition in the case of In re: Adelphi Group, the Fifth Court reminds: “Although parties may expend time and money if they are ordered to arbitration improperly, delay and expense—standing alone—will not render the final appeal inadequate. Further, mandamus as a remedy for review of orders compelling arbitration should be limited to the comparatively rare cases where the legislature has through statute expressed a public policy that overrides the public policy favoring arbitration.” No. 05-16-01060-CV (Sept. 22, 2016) (mem. op.)

If You Might Be Violating Public Policy, Make Sure to Include an Arbitration Clause

October 12, 2015Jenner & Block took on the representation of Parallel Networks in patent infringement litigation. Their contingency fee agreement provided that Parallel was responsible for the payment of expenses, but Parallel ran up a $500,000 deficit before expenses were finally paid out of proceeds from settlement in another lawsuit. Jenner withdrew from the case, citing a termination clause that allowed it to withdraw if continuing was not in its economic interest. After the patent cases settled under successor counsel, Jenner invoked arbitration and sought to recover $10 million in fees. The arbitrator ruled that Jenner’s withdrawal was justified and awarded $3 million as an “appropriate and fair” portion of the contingent fee recovery, as provided in the parties’ contract. The trial court confirmed the award, and the Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed. The Court declined Parallel’s invitation to declare that the fee agreement was against public policy, holding that the statutory grounds for vacating an award under the FAA are exclusive, and that public policy therefore could not serve to vacate the award.

Parallel Networks, LLC v. Jenner & Block LLP, No. 05-13-00748-CV