This is a crosspost from 600Hemphill, which follows business litigation in the Texas Supreme Court.

In Pike v. Texas EMC Mangagment LLC, ”‘Value’ was defined in the jury charge as ‘”Market Value,”’ the amount that would be paid in cash by a willing buyer who desires to buy, but is not required to buy, to a willing seller who desires to sell, but is under no necessity of selling.’”

Expert testimony sought to establish a $4.1 million value for the relevant plant and equipment, which the Texas Supreme Court rejected for three reasons:

Expert testimony sought to establish a $4.1 million value for the relevant plant and equipment, which the Texas Supreme Court rejected for three reasons:

“First, … [e]vidence of the purchase price of the Partnership’s property is insufficient under that measure because it does not establish the fair market value of the property at a different time.”

“Second, …[c]ourts employing an actual-value measure have held that ‘[f]rom that starting point, adjustments are made for wear and tear, depreciation, and other pertinent factors.’ Having examined the record, we disagree with the plaintiffs that [the expert] took anything other than purchase price—and a 20% escalation factor—into account in opining about the value of the plant and equipment.”

“Third, [the expert] did not attempt to tie the value of the plant to the market value of the

Partnership, which was the only measure of damages in the jury charge. He did not address whether any debt encumbered the plant, for example, or otherwise testify regarding how loss of the plant and equipment impacted the value of the Partnership as a whole.” (emphasis added, citations omitted)

The Court also rejected efforts to corroborate the expert’s testimony with lay-opinion testimony by an owner, because that testimony was based on book rather than actual value. Foreclosure-sale price was similarly irrelevant. No. 17-0557 (June 19, 2020).

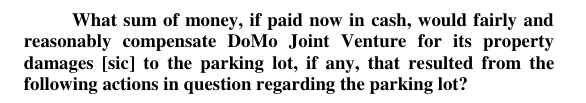

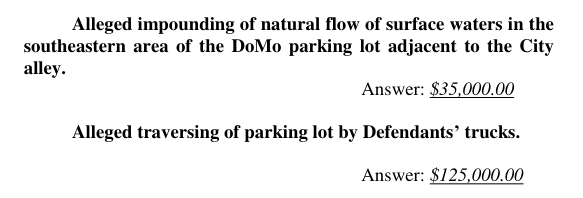

In Calitex LLC v. Big Lot Stores, LLC, the Fifth Court reminded that “evidence of the amounts charged and paid, standing alone, is no evidence that such payment was reasonable and necessary.” Here, a tenant submitted invoices and testimony regarding the need for repairs and the amounts paid, but failed to present any additional evidence demonstrating the reasonableness of the charges.

In Calitex LLC v. Big Lot Stores, LLC, the Fifth Court reminded that “evidence of the amounts charged and paid, standing alone, is no evidence that such payment was reasonable and necessary.” Here, a tenant submitted invoices and testimony regarding the need for repairs and the amounts paid, but failed to present any additional evidence demonstrating the reasonableness of the charges.

(This is a crosspost from

(This is a crosspost from