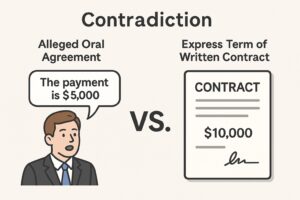

In Roxo Energy, LLC v. Baxsto, LLC, LLC, the Texas Supreme Court addressed (again) the element of justifiable reliance, in the context of alleged oral promises that contradicted written agreements.

In Roxo Energy, LLC v. Baxsto, LLC, LLC, the Texas Supreme Court addressed (again) the element of justifiable reliance, in the context of alleged oral promises that contradicted written agreements.

Specifically, the Court held that claims based on oral representations about the lessee’s intent to develop the mineral lease, rather than “flip” it, failed ecause the written lease expressly let the lessee transfer its interest with no obligation to drill or develop the land. The Court emphasized that “an unqualified contractual right to transfer a lease contradicts a prior oral promise not to do so,” making reliance on such oral promises unjustifiable.

The Court also rejected claims based on alleged misrepresentations about bonus payments. The only written commitment about bonus payments was a “most favored nations” clause, which was not breached. The Court explained that the absence of any language in the written agreements confirming the alleged oral representations about bonus amounts was itself a “red flag negating justifiable reliance””–“[T]he prudent response is to demand that the parties’ discussions be reflected in the writing—not to sign an agreement that makes no mention of the promises and then try to hold your counterparty to them anyway.”

No. 23-0564, Tex. May 9, 2025.