An unfortunate event involving citation to “hallucinated” case authority ended with this sanctions order. Three lessons can be learned:

An unfortunate event involving citation to “hallucinated” case authority ended with this sanctions order. Three lessons can be learned:

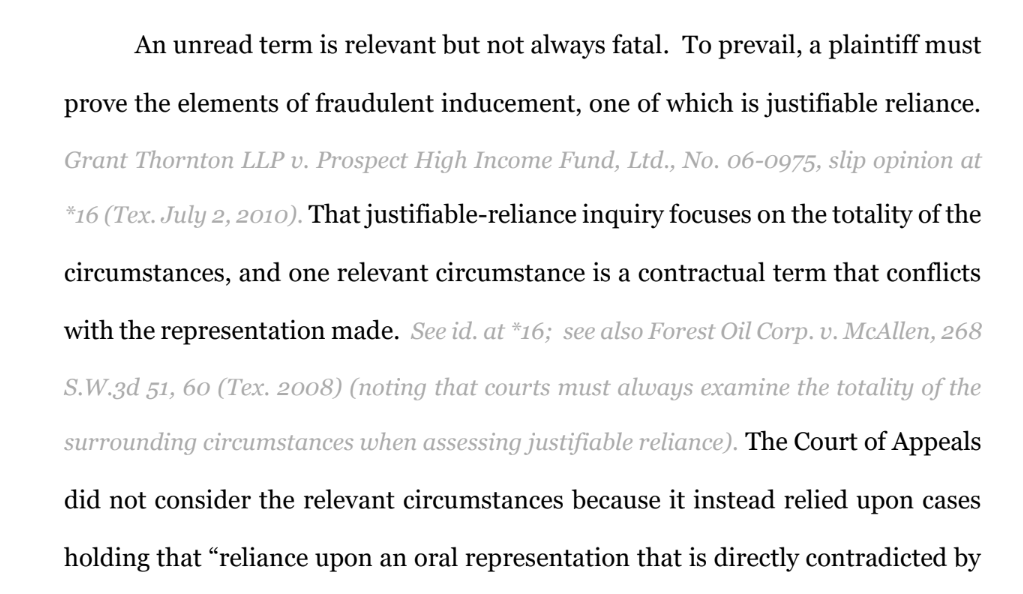

- Avoid using Gen AI to do serious case research. There’s nothing wrong with asking it research questions to get ideas, and that can be quite helpful as part of an overall use of Gen AI to help write — so long as you remember that every citation it returns has to be checked for accuracy. Gen AI programs can look like databases, and they can act like databases, but Gen AI programs are not databases.

- If it’s too good to be true, it is. The problem in this case arose from a hallucinated Texas Supreme Court case from the late 19th Century that involved materially similar facts. If that was a Westlaw search result, it would require double-checking because it’s just so unlikely. The best “tell” that Gen AI is hallucinating is that it’s giving you exactly what you want to hear.

- Don’t lie behind the log. I don’t know all the facts of this case, but the order says that the appellant’s counsel did not take prompt action when the problem with the hallucinated citations was first brought to light. If something has been cited in error, get out in front of the error before your opponent and the court has to spend needless time and energy helping rectify it.