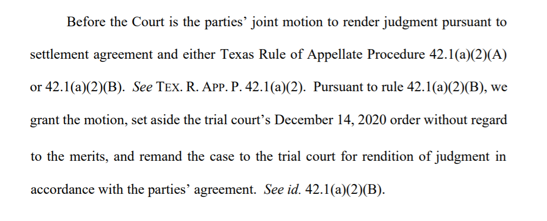

Compton v. Compton, No. 05-21-00163-CV (Nov. 1, 2021), provides a good framework for approaching a settlement on appeal that includes action related to the trial-court order under appeal:

Category Archives: Settlement

Cooper v. Cooper presented an issue about the entry of a consent judgment after one of the parties withdrew its approval. The Fifth Court found that by the time judgment was rendered, the trial court was on notice about the issue with that party’s consent, making it an abuse of discretion to proceed to entry of judgment based on the earlier agreement. No. 05-20-00507-CV (May 4, 2021) (mem. op.) This topic can be surprisingly challenging in Texas state practice given the wide range of agreements covered by Tex. R. Civ. P. 11 — this is a 2019 article that I co-authored about some of those procedural issues.

Cooper v. Cooper presented an issue about the entry of a consent judgment after one of the parties withdrew its approval. The Fifth Court found that by the time judgment was rendered, the trial court was on notice about the issue with that party’s consent, making it an abuse of discretion to proceed to entry of judgment based on the earlier agreement. No. 05-20-00507-CV (May 4, 2021) (mem. op.) This topic can be surprisingly challenging in Texas state practice given the wide range of agreements covered by Tex. R. Civ. P. 11 — this is a 2019 article that I co-authored about some of those procedural issues.

Gharavi owned a business that won an arbitration against Khademazad. Gharavi sued to enforce the award, and along the way, made a comment about Khademazad and the award on Yelp. The parties resolved their differences and entered a settlement agreement of the lawsuit about the award, in which Khademazad released all claims “directly or indirectly attributable to the transaction or occurences made the basis of this lawsuit.” Several weeks later, Khademazad sued for libel and similar claims based on the Yelp post. The Fifth Court found that this suit was barred by the release: “Without question, the Yelp review was, if not directly, then indirectly attributable to Khademazad’s failure to pay for Aidris’s services and the lawsuit that followed. Khademazad’s claims here are clearly within the subject matter of the release.” Gharavi v. Khademazad, No. 05-20-00083-CV (Feb. 2, 2021) (mem. op.).

The first rule of confidential settlements is: we don’t talk about confidential settlements

November 4, 2016GDL Masonry Supply, Inc. v Lopez and Rapid Masonry Supply, Inc. (November 2, 2016) is a handy opinion to hand your clients after they sign a settlement agreement requiring confidentiality. It is a risk too many clients do not take seriously enough (see, e.g., “Girl costs father $80,000 with ‘SUCK IT’ Facebook post“).

In GDL, the Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed summary judgment in favor of Rapid, the plaintiff, who refused to pay under a settlement agreement because GDL failed to satisfy the confidentiality requirements of the agreement. The facts were too common. GDL brought suit against Rapid, which settled by way of an agreement that required confidentiality and Rapid to make a series of $10,000 payments totaling $60,000 to GDL. GDL then told a third party that Rapid had stolen from it, that GDL won the lawsuit, and that Rapid owed GDL money as a result. When Rapid discovered what GDL said about their litigation, it sued asserting that it had no obligation to make the remaining settlement payments and also seeking attorney’s fees for breach of the confidentiality language. The trial court granted summary judgment to Rapid, holding that the confidentiality provision was breached, that Rapid had no obligation to make further payments, and awarding attorney’s fees.

GDL’s argument on appeal did not deny the disclosure of the settlement, but instead challenged the materiality of the confidentiality provision. The Dallas Court of Appeals made swift work in rejecting this argument, noting that the settlement agreement itself stated that the confidentiality paragraph “is a material provision of this Agreement and that any breach of the terms and conditions of [the paragraph] shall be a material breach of this Agreement.” The Court held that the contract’s language was binding.

GDL Masonry Supply, Inc. v Lopez and Rapid Masonry Supply, Inc.