My thoughtful friend Arturo Ayala recently wrote this informative short article as to when partial supersedeas bonds may be allowed.

Category Archives: Supersedeas

Putnam wanted $6,000 back from the county courts, that he had posted earlier as a supersedeas deposit. Unsuccessful in obtaining the money from the clerk’s office, he sued the county clerk, who obtained dismissal on jurisdictional grounds. The Fifth Court, after modifying the dismissal to be “without prejudice,” encouraged Putnam to seek relief from the probate judge rathe than the clerk:

Putnam wanted $6,000 back from the county courts, that he had posted earlier as a supersedeas deposit. Unsuccessful in obtaining the money from the clerk’s office, he sued the county clerk, who obtained dismissal on jurisdictional grounds. The Fifth Court, after modifying the dismissal to be “without prejudice,” encouraged Putnam to seek relief from the probate judge rathe than the clerk:

Putnam’s claim is for the return of a deposit he paid to supersede a probate court order issued in connection with the administration of Powell’s estate. We conclude his claim arises from an estate administration and is thus a probate proceeding. Further, Putnam’s claim does not fit within the examples of “matters related to a probate proceeding” in [Tex. Probate Code] § 31.002, most of which involve claims brought by or against an estate’s personal representative. The probate court had exclusive jurisdiction over Putnam’s claim, and the county court did not err in granting Warren’s plea to the jurisdiction.

No. 05-23-00235-CV (July 26, 2024) (mem. op.).

The classic children’s book “Caps for Sale” involved a peddler who had many caps. So too, section 52.006 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code, which caps the amount of a supersedeas bond at $25 million, but as to which “[t]here is a split of authority on whether the $25 million statutory cap … applies per individual judgment debtor or per judgment.”

The classic children’s book “Caps for Sale” involved a peddler who had many caps. So too, section 52.006 of the Texas Civil Practice & Remedies Code, which caps the amount of a supersedeas bond at $25 million, but as to which “[t]here is a split of authority on whether the $25 million statutory cap … applies per individual judgment debtor or per judgment.”

In Greystar Devel. & Constr., L.P. v. Williams, the Fifth Court held that the cap applies per debtor, joining the Tyler Court of Appeals in so holding, but diverging from the analysis of the San Antonio Court of Appeals. Review by the state supreme court seems likely on this important but elusive issue of statutory interpretation. No. 05-23-001168-CV (April 10, 2024).

Note that new supersedeas rules are now in effect, changing the rules about “alternate security” (for actions filed after September 2023), and eliminating the longstanding requirement the court clerk approve a supersedeas bond before it becomes effective (effective for all actions).

In Moby-Dick, Captain Ahab nailed a gold coin to the mast as an incentive to spot the white whale. In Combs v. Crepeau, the judgment debtor deposited a gold coin into the trial court’s registry as part of the supersedeas for a substantial civil judgment. The Fifth Court distinguished a permissible order requring a cash deposit from an impermissible order appointing a post-judgment receiver (in the supersedeas setting), noting: “Placing money into the court’s registry is a means of keeping the money safe.” No. 05-23-00088-CV (Aug. 21, 2023) (mem. op.).

In Moby-Dick, Captain Ahab nailed a gold coin to the mast as an incentive to spot the white whale. In Combs v. Crepeau, the judgment debtor deposited a gold coin into the trial court’s registry as part of the supersedeas for a substantial civil judgment. The Fifth Court distinguished a permissible order requring a cash deposit from an impermissible order appointing a post-judgment receiver (in the supersedeas setting), noting: “Placing money into the court’s registry is a means of keeping the money safe.” No. 05-23-00088-CV (Aug. 21, 2023) (mem. op.).

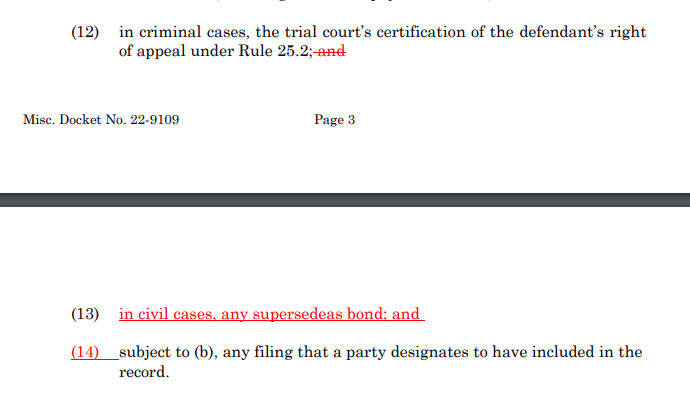

The supreme court has preliminarily approved this addition to the Tex. R. App. P. about the clerk’s record:

Hopefully, this change will make it easier to follow Tex. R. App. 43.5 (and its supreme court analog), which says: “When a court of appeals affirms the trial court judgment, or modifies that judgment and renders judgment against the appellant, the court of appeals must render judgment against the sureties on the appellant’s supersedeas bond, if any, for the performance of the judgment and for any costs taxed against the appellant.”

Hopefully, this change will make it easier to follow Tex. R. App. 43.5 (and its supreme court analog), which says: “When a court of appeals affirms the trial court judgment, or modifies that judgment and renders judgment against the appellant, the court of appeals must render judgment against the sureties on the appellant’s supersedeas bond, if any, for the performance of the judgment and for any costs taxed against the appellant.”

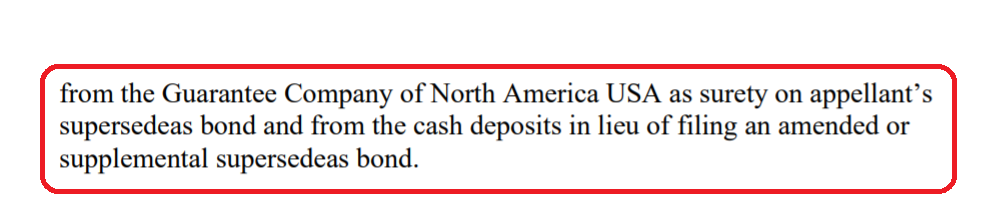

The Fifth Court recently recalled a mandate and amended its own judgment to include the surety on a supersedeas bond as an additional party. The motion primarily cited Whitmire v. Greenridge Place Apts., 333 S.W.3d 255, 260-61 (Tex. App. – Houston [1st Dist.] 2010, pet. dism’d w.o.j.). A big 600Commerce thanks to Ben Taylor for pointing out this order to me (and correcting the pet. history on my original post)

In a supersedeas-bond dispute, the Fifth Court held: “When Real Parties withdrew the deposit without the court’s authorization, they assumed the risk that their withdrawal might be improper and that the court might require them to redeposit the funds. Moreover, Real Parties received the full benefit of having the partition-and-sale order superseded during the years that the order was on appeal. The trial court may determine whether equity requires ordering Real Parties to return the supersedeas to the court’s registry for the court to determine the amount of Relators’ damages during the appeal.” In re Pelley, No. 05-21-00314-CV (Aug. 31, 2021) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

A group of investors (“FPH”) in a business (“FSG”) sought the appointment of a receiver to review and report on the finances of FSG. The trial court (1) agreed, and then (2) allowed FSG to supersede the order with a $10,000 bond while it took an interlocutory appeal, but then (3) allowed FPH to post a “counter-supersedeas bond” of $11,875 so that the receiver’s work could proceed during the interlocutory appeal. The Fifth Court found that “[TRAP] 24.2(a)(3) expressly permitted the trial court to allow FPH to post a counter-supersedeas bond,” and then found the bond amount to be appropriate in light of “[t]he fact that FSG continues to have sole control of its management” and the evidence presented about FSG’s financial situation. Five Star Global, LLC v. Hulme, No. 05-20-00940-CV (March 2, 2021).

A group of investors (“FPH”) in a business (“FSG”) sought the appointment of a receiver to review and report on the finances of FSG. The trial court (1) agreed, and then (2) allowed FSG to supersede the order with a $10,000 bond while it took an interlocutory appeal, but then (3) allowed FPH to post a “counter-supersedeas bond” of $11,875 so that the receiver’s work could proceed during the interlocutory appeal. The Fifth Court found that “[TRAP] 24.2(a)(3) expressly permitted the trial court to allow FPH to post a counter-supersedeas bond,” and then found the bond amount to be appropriate in light of “[t]he fact that FSG continues to have sole control of its management” and the evidence presented about FSG’s financial situation. Five Star Global, LLC v. Hulme, No. 05-20-00940-CV (March 2, 2021).

Tom Tillotson sought to appeal two turnover orders without posting a supersedeas bond. (The Fifth Court’s opinion reminds: “A turnover order in the nature of a mandatory injunction is a final judgment that may be superseded.”) The Court agreed with him that “the amounts [in the relevant accounts] do not constitute compensatory damages,” but disagreed as to the effect of that conclusion. Because the turnover order “functions as a mandatory injunction,” it “constitutes a judgment for something other than money or an interest in property and, accordingly [Tex. R. App. P.] 24.2(a)(3) controls” rather than Rule 24.2(a)(1) about the appeal of money judgments. “Under rule 24.2(a)(3), the trial court must set a bond that will adequately protect the judgment creditor against loss or damage that the appeal might cause.” In re Estate of Tillotson, No. 05-20-00258-CV (Sept. 15, 2020) (mem. op.)

Tom Tillotson sought to appeal two turnover orders without posting a supersedeas bond. (The Fifth Court’s opinion reminds: “A turnover order in the nature of a mandatory injunction is a final judgment that may be superseded.”) The Court agreed with him that “the amounts [in the relevant accounts] do not constitute compensatory damages,” but disagreed as to the effect of that conclusion. Because the turnover order “functions as a mandatory injunction,” it “constitutes a judgment for something other than money or an interest in property and, accordingly [Tex. R. App. P.] 24.2(a)(3) controls” rather than Rule 24.2(a)(1) about the appeal of money judgments. “Under rule 24.2(a)(3), the trial court must set a bond that will adequately protect the judgment creditor against loss or damage that the appeal might cause.” In re Estate of Tillotson, No. 05-20-00258-CV (Sept. 15, 2020) (mem. op.)

“…the power granted by section 22.221(a) of the government code is not a power that is granted to prevent damage to the appellant pending appeal.’ ‘That purpose is served by the statutes allowing appellants to supersede judgments by posting an appropriate bond.’ Rather, the power to issue a writ of injunction is limited to the purpose of protecting appellate jurisdiction.

“…the power granted by section 22.221(a) of the government code is not a power that is granted to prevent damage to the appellant pending appeal.’ ‘That purpose is served by the statutes allowing appellants to supersede judgments by posting an appropriate bond.’ Rather, the power to issue a writ of injunction is limited to the purpose of protecting appellate jurisdiction.

Here, relators assert that the pending foreclosure threatens this Court’s jurisdiction over their existing appeal. But unlike the cases cited by relators involving appeals of interlocutory orders, the foreclosure of the property at issue does not moot their claims in the appeal and, thus, does not implicate the Court’s jurisdiction over the appeal.” In re Day Investment Group, No. 05-20-00643-CV (July 2, 2020) (mem. op.) (citation omitted, emphasis added).

After the Confederate disaster at Gettysburg in 1863, the wily Robert E. Lee held off Ulysses Grant for two more years in a series of battles. Dallas’s Confederate statuary is proving similarly wily; after an initial stay to receive full briefing on the point, the Fifth Court agreed that a writ of injunction was appropriate to maintain the downtown Confederate memorial (right, in part): “The Monument was created in 1896 and has already been relocated once. There is no guarantee that the removal process will be seamless and without damage to the Monument, or that if it is ultimately returned to Pioneer Cemetery that it will be in the same condition as it is today.” The Court required the plaintiff to post a $50,000 bond. It also found that a similar application was moot as to a statute of Lee that has already been sold and reinstalled in the Big Bend area of far West Texas (Texas, incidentally, being the location of Lee’s last command in the U.S. Army before siding with the Confederacy.) In re: Return to Lee Park, No. 05-19-00774-CV (Oct. 10, 2019) (mem. op.)

After the Confederate disaster at Gettysburg in 1863, the wily Robert E. Lee held off Ulysses Grant for two more years in a series of battles. Dallas’s Confederate statuary is proving similarly wily; after an initial stay to receive full briefing on the point, the Fifth Court agreed that a writ of injunction was appropriate to maintain the downtown Confederate memorial (right, in part): “The Monument was created in 1896 and has already been relocated once. There is no guarantee that the removal process will be seamless and without damage to the Monument, or that if it is ultimately returned to Pioneer Cemetery that it will be in the same condition as it is today.” The Court required the plaintiff to post a $50,000 bond. It also found that a similar application was moot as to a statute of Lee that has already been sold and reinstalled in the Big Bend area of far West Texas (Texas, incidentally, being the location of Lee’s last command in the U.S. Army before siding with the Confederacy.) In re: Return to Lee Park, No. 05-19-00774-CV (Oct. 10, 2019) (mem. op.)

In Cruz v. Ghani, a judgment creditor executed on the judgment debtor’s condominium – realizing a sale price of $25,000, despite a market value of $217,500 – only to have the judgment later reversed on appeal. In the ensuing lawsuit about wrongful execution, the (former) judgment debtor prevailed and won judgment for the market value. The trial court required a supersedeas bond for the full amount and the Fifth Court affirmed. It concluded that the purpose of such an award was to compensate for loss, and thus did not fall within a line of authority holding that awards for equitable disgorgement do not have to be bonded, as they “are not based on an actual pecuniary loss suffered by the plaintiff, but on the defendant’s ill-gotten gains.” No. 05-17-00566-CV (Jan. 17, 2018) (mem. op.)

In Cruz v. Ghani, a judgment creditor executed on the judgment debtor’s condominium – realizing a sale price of $25,000, despite a market value of $217,500 – only to have the judgment later reversed on appeal. In the ensuing lawsuit about wrongful execution, the (former) judgment debtor prevailed and won judgment for the market value. The trial court required a supersedeas bond for the full amount and the Fifth Court affirmed. It concluded that the purpose of such an award was to compensate for loss, and thus did not fall within a line of authority holding that awards for equitable disgorgement do not have to be bonded, as they “are not based on an actual pecuniary loss suffered by the plaintiff, but on the defendant’s ill-gotten gains.” No. 05-17-00566-CV (Jan. 17, 2018) (mem. op.)

Acra v. Bonaudo illustrates the “falling dominoes” problem that can arise from discovery issues. Appellants sought to supersede a judgment with relatively small bonds. The district court found problems with their discovery responses, which interfered with their ability to establish a low net worth at the hearing about bond size. The Fifth Court affirmed: “On the record before us, we deny the request to vacate the trial court’s orders. Without evidence of all of Acra’s and Secner HR’s assets and liabilities, the trial court could not determine their individual net worth. And, without a determination of their individual net worth, the amount of bond, set in accordance with civil practice and remedies code section 52.006 and appellate rule 24.2(a)(1), was not an abuse of discretion.” No. 05-17-00451-CV (Dec. 8, 2017) (mem. op.)

Acra v. Bonaudo illustrates the “falling dominoes” problem that can arise from discovery issues. Appellants sought to supersede a judgment with relatively small bonds. The district court found problems with their discovery responses, which interfered with their ability to establish a low net worth at the hearing about bond size. The Fifth Court affirmed: “On the record before us, we deny the request to vacate the trial court’s orders. Without evidence of all of Acra’s and Secner HR’s assets and liabilities, the trial court could not determine their individual net worth. And, without a determination of their individual net worth, the amount of bond, set in accordance with civil practice and remedies code section 52.006 and appellate rule 24.2(a)(1), was not an abuse of discretion.” No. 05-17-00451-CV (Dec. 8, 2017) (mem. op.)

With all the TCPA cases running through the appellate courts, it’s worth taking a quick look at one procedural issue. The question presented by way of motion to the Court of Appeals was whether the appellants were required to supersede the attorney fees awarded to the defendants in a judgment dismissing the plaintiffs’ business disparagement claims. The appellate court held that attorney fees are not damages, and therefore the trial court did not err in denying the defendants’ motion to raise the supersedeas amount to include the attorney fees.

Mansik & Young Plaza LLC v. K-Town Mgmt., LLC, No. 05-15-00353-CV

When a judgment judgment for breach of contract is entered that includes an award of attorney fees, the defendant is generally not required to supersede that fee award in order to suspend judgment. Instead, the defendant only has to supersede post-judgment interest on the award for the expected duration of the appeal. In this case, Highland Capital Management was awarded $2.8 million in attorney fees, but the defendant only bonded out $287,000. Highland moved to increase the supersedeas bond, arguing that the attorney fees were actually compensatory damages because the parties’ contract contained a clause requiring the defendant to pay Highland’s fees in the event of a breach. The Court of Appeals rejected that argument, essentially concluding that an award of attorney fees under the contract was no different than an award of attorney fees under Chapter 38 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code (which Highland had also sought in its pleadings and at trial).

Highland Capital Mgmt., L.P. v. Daugherty, No. 05-14-01215-CV