Five Tips for Hurricane Harvey Litigation (a version of this article is in this week’s Texas Lawbook)

In the course of reviewing the Fifth Circuit’s commercial cases for the 600 Camp blog, I have read many opinons about disputes arising from Hurricane Katrina cases. In light of the havoc recently created by Hurricane Harvey, I wanted to share five observations to prepare for the litigation that will inevitably result.

- Record the facts.

Any lawsuit creates tension between the past and the future. The parties want to move on, and put the expense and stress of litigation behind them. But the legal case forces them to revisit the past.

That tension is particularly acute after a disaster such as Harvey, which forced people and businesses to endure incredible stress, while making them then revisit that trauma to protect their legal rights in court. The – entirely understandable – desire to move on, must be squared with the need to take the time to preserve evidence.

Consider St. Bernard Parish v. Lafarge North America, a case about the destruction of a bridge during Hurricane Katrina. While the parties offered extensive expert testimony about what caused the damage, the summary judgment proceedings turned in no small part on the facts of what happened during the storm, including facts established by photographs.

A party facing litigation should consider – as awkward as it can be while recovering from a life-disrupting event – what facts seem obvious now but may fade from memory as time goes on. To the extent possible, some thought should be given to:

- maintaining electronic records, even if the hardware appears damaged at first blush;

- writing down a “log” of relevant conversations and events about important events;

- storing any relevant physical objects, for potential future analysis by experts; and

- simply writing down basic information about names, addresses, phone numbers, and the like.

In a case arising from a natural disaster, courts will likely be forgiving as to claims of spoliation. But lost information is lost, and its absence can later effect the resolution of a legal case.

- Help the people.

The fact evidence in the Lafarge case also included eyewitness testimony, which proved critical to defeating the defendant’s summary judgment motion. Just as a photograph can deteriorate, a person’s memory can fade. And the likelihood of that occurring can only increase when the person is placed under the severe stress of a natural disaster.

Any “team” confronted with a legal challenge by Harvey – a business, a professional organization, or even a family – should be mindful of the psychological effects of that stress, and encourage counseling for depression, substance abuse, and other such problems when their first signs appear. Of course, that is a good practice in any event. But its potential side benefit to a legal case is real and worth remembering.

- Remember three definitions.

The factual and legal issues that will ultimately go to trial in cases about Harvey simply cannot be predicted with any specificity. But in the short run, three basic legal concepts are likely to pervade business dealings related to the storm:

- The Texas pattern jury instruction about “duress” defines it as “the mental, physical, or economic coercion of another, causing that party to act contrary to his free will and interest.”

- While “force majeure” is ordinarily defined by a specific contract, it generally refers to an “extraordinary event or circumstance beyond the control of the parties,” and often does not excuse a party’s non-performance entirely, but only suspends it for the duration of the event.

- “Impossibility of performance” is defined by the Restatement (Second) of Contracts as occurring “[w]here, after a contract is made, a party’s performance is made impracticable without his fault by the occurrence of an event the non-occurrence of which was a basic assumption on which the contract was made, his duty to render that performance is discharged, unless the language or the circumstances indicate the contrary.”

Awareness of these concepts can potentially avoid problems down the road, as well as identify topics and issues that require special attention today.

- “Two-deep leadership.”

The Boy Scouts of America strictly follows a policy of “two-deep leadership,” under which two adults should be present at all times when interacting with youth. One benefit of that policy is to avoid “he-said, she-said” disputes between two eyewitnesses with no third–party corroboration. In the stress of dealing with the aftermath of Harvey, involving a business colleague or a friend in important discussions may help the future resolution of a legal matter, if a dispute arises about what was said in those discussions.

- Crowdsource, wisely.

For good or ill, social media has come a long way since Hurricane Katrina. Used judiciously, it can be a good source of information about late-breaking news or the reputation of a particular business. And it can provide a valuable outlet for self-expression after the trauma of Harvey.

But social media posts can survive much longer than the thoughts that prompted them, and rash comments about people or events can come back to haunt the person who makes an ill-advised post. Social media is a valuable conduit for information, and at the same time, it is a reliable creator and collector of potential evidence.

Conclusion

Faced with the reality of recovery from one of the worst storms in the nation’s history, planning for future litigation may seem to be a distant worry. But the foundation for that litigation is being put in place today, intentionally or unintentionally. These five basic ideas may provide ways to place that foundation in a more orderly manner, resulting in a stronger end product.

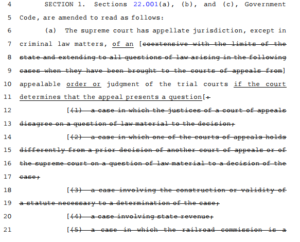

The Fifth Court found a sufficient fact issue to reverse a summary judgment in 6200 GP LLC v. Multi Service Corp., in which an affiant’s testimony was found not to be conclusory when:

The Fifth Court found a sufficient fact issue to reverse a summary judgment in 6200 GP LLC v. Multi Service Corp., in which an affiant’s testimony was found not to be conclusory when: