KPitch intervened in a lawsuit and obtained a temporary injunction against FSD. FSD appealed the injunction and sought mandamus relief against the intervention. KPitch then nonsuited the claims that were the basis for the injunction, and the Fifth Court agreed with KPitch that this action made the appellate proceedings moot. FSD argued that the appeal should proceed because KPitch had refiled the claims in an improper effort to obtain a severance, but the Court did not see this argument as creating an exception to the general rule about the effect of a nonsuit. Frisco Square Developers LLC v. KPitch Enterprises, LLC, No. 05-16-00992-CV (June 22, 2017) (mem. op.)

KPitch intervened in a lawsuit and obtained a temporary injunction against FSD. FSD appealed the injunction and sought mandamus relief against the intervention. KPitch then nonsuited the claims that were the basis for the injunction, and the Fifth Court agreed with KPitch that this action made the appellate proceedings moot. FSD argued that the appeal should proceed because KPitch had refiled the claims in an improper effort to obtain a severance, but the Court did not see this argument as creating an exception to the general rule about the effect of a nonsuit. Frisco Square Developers LLC v. KPitch Enterprises, LLC, No. 05-16-00992-CV (June 22, 2017) (mem. op.)

Twice in one week, the Fifth Court affirmed substantial awards of exemplary damages. I anticipate posts in the days ahead about the details of these cases, but for now, simply note these important holdings:

Twice in one week, the Fifth Court affirmed substantial awards of exemplary damages. I anticipate posts in the days ahead about the details of these cases, but for now, simply note these important holdings:

- Bombardier Aerospace Corp. v. SPEP Aircraft Holdings LLC, No. 05-16-00086-CV (June 22, 2017) (mem. op.), a case about the condition of an expensive private jet, affirmed “a verdict in appellees’ favor on both claims and awarded $2,694,160 in actual damages and $5,388,320 in exemplary damages,” and

- Wells Fargo Bank, N.A. v. Militello, No. 05-15-01252-CV (June 20, 2017) (mem. op.) affirmed (after a remittitur) an award of approximately $2.7 million and roughly $1 million in actual damages.

A famous Shakespeare poem laments: “What win I, if I gain the thing I seek?

A famous Shakespeare poem laments: “What win I, if I gain the thing I seek?

A dream, a breath, a froth of fleeting joy. . . . ” These thoughts could also be the lament of the landlord / appellee in Analytical Technology Consultants v. Axis Capital, who obtained a summary judgment against a tenant in default on a lease. Unfortunately, while the tenant did not respond to the summary judgment motion, it pointed out in a motion for new trial that the landlord had failed to include a credit against the accelerated balance as required by the lease’s remedies provision. The landlord sought to preserve its judgment on appeal by pointing to the evidence it submitted in response to the motion for new trial, which it said included the relevant calculation, but the Fifth Court disagreed: ” An attachment to a motion for new trial is not evidence. To constitute evidence, the attachment must be introduced at the hearing on the motion for new trial. If there is no hearing, then the document never becomes evidence.” (citations omitted). No. 05-16-00281-CV (June 19, 2017) (mem. op.)

In the department of “ra re bird sightings,” the case of Hollingsworth v. Walaal Corp. involved an appeal, under the newly-revised Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 145, to a trial court order requiring an appellant to pay for a reporter’s record. The appellant filed an affidavit of inability to pay costs and the trial court had an evidentiary hearing on the appellees’ challenge to it. Recognizing that the appellant did not offer tax returns or the like, the Fifth Court reversed, finding that his “testimony was uncontroverted” and that “[a]lthough the trial court was required to evaluate Hollingsworth’s credibility, the trial court was not free to completely disregard the only evidence establishing his inability to pay costs when no evidence was offered in rebuttal.” No. 05-17-00555-CV (June 9, 2017) (mem. op.)

re bird sightings,” the case of Hollingsworth v. Walaal Corp. involved an appeal, under the newly-revised Texas Rule of Civil Procedure 145, to a trial court order requiring an appellant to pay for a reporter’s record. The appellant filed an affidavit of inability to pay costs and the trial court had an evidentiary hearing on the appellees’ challenge to it. Recognizing that the appellant did not offer tax returns or the like, the Fifth Court reversed, finding that his “testimony was uncontroverted” and that “[a]lthough the trial court was required to evaluate Hollingsworth’s credibility, the trial court was not free to completely disregard the only evidence establishing his inability to pay costs when no evidence was offered in rebuttal.” No. 05-17-00555-CV (June 9, 2017) (mem. op.)

The Dallas Morning News reports the recent death of former Dallas Court of Appeals Justice David Lewis, who resigned from that Court last year to combat alcoholism and depression. The story sounds a warning note for all in the legal profession about the importance of mental health.

Dahlheimer sought a writ of injunction in the court of appeals to stay proceedings involving a receivership about the sale of a home. The Fifth Court found that it lacked jurisdiction, noting that its injunctive power is limited to “jurisdiction over the subject matter of a pending appeal,” and that “[t]he power to grant a temporary writ of injunction to prevent damages which would otherwise flow to alitigant who has an apppeal pending rests exclusively with the trial court.” In re Dahlheimer, No. 05-17-00556-CV (June 8, 2017) (mem. op.)

Dahlheimer sought a writ of injunction in the court of appeals to stay proceedings involving a receivership about the sale of a home. The Fifth Court found that it lacked jurisdiction, noting that its injunctive power is limited to “jurisdiction over the subject matter of a pending appeal,” and that “[t]he power to grant a temporary writ of injunction to prevent damages which would otherwise flow to alitigant who has an apppeal pending rests exclusively with the trial court.” In re Dahlheimer, No. 05-17-00556-CV (June 8, 2017) (mem. op.)

A quick reminder on summary judgment procedure appears in Autosource Dallas LLC v. Addison Aeronautics LLC:

A quick reminder on summary judgment procedure appears in Autosource Dallas LLC v. Addison Aeronautics LLC:

- “A movant is required to provide twenty-one days’ notice when setting a summaryjudgment. This twenty-one day requirement is designed to give

the nonmovant sufficient time to prepare and file a response for the original setting.” - “The twenty-one-day notice requirement does not however apply to a resetting of the hearing, so long as the nonmovant received twenty-one days’ notice of the original hearing.”

- For a recheduled hearing, the movant “needed only to give reasonable notice that the hearing on its summary judgment had been rescheduled. Reasonable notice means at least seven days before the hearing because a nonmovant

may only file a response to a motion for summary judgment not later than seven days prior to the date of the hearing without leave of court.”

No. 05-16-00838-CV (June 9, 2017) (mem. op.)

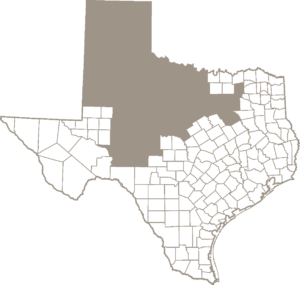

The high-profile mandamus case of In re: Paxton provides a general reminder about geographic bounds on Texas trial courts: “Jurisdiction over the cases vested immediately in the Harris County district courts when respondent signed the transfer order. The Texas Constitution does not allow the 416th Judicial District Court to sit outside of the Collin County seat, McKinney, absent express statutory authority. Tex. Const. art. V, § 7. The only authority by which this may occur is [Code of Criminal Procedure] article 31.09, which requires consent of the parties. Thus, absent effective application of article 31.09, respondent may not continue to preside over the cases or utilize the services of the court reporter, court coordinator, or clerk of the court of original venue. Relator has unequivocally stated that he did not consent to respondent continuing to preside over the cases or otherwise acting in accordance with article 31.09, and no written consent appears in our record. Accordingly, under the plain language of the statute, respondent is without authority to continue to preside over the cases and is also without authority to issue orders or directives maintaining the case files in Collin County. Consequently, all orders issued by respondent after he signed the April 11, 2017 transfer order are void.” No. 05-17-00507-CV (May 30, 2017).

Last Friday, the Texas Supreme Court denied mandamus relief in a high-profile dispute about the proper format in which to produce electronic records, but provided extensive guidance about the framework and factors that should decide such disputes, and remanded for reconsideration in light of that guidance. In a nutshell: “Under our discovery rules, neither party may dictate the form of electronic discovery. The requesting party must specify the desired form of production, but all discovery is subject to the proportionality overlay embedded in our discovery rules and inherent in the reasonableness standard to which our electronic-discovery rule is tethered. The taproot of this discovery dispute is whether production in native format is reasonable given the circumstances of this case. Reasonableness and its bedfellow, proportionality, require a case-by-case balancing of jurisprudential considerations,which is informed by factors the discovery rules identify as limiting the scope of discovery and geared toward the ultimate objective of “obtain[ing] a just,fair, equitable and impartial adjudication” for the litigants “with as great expedition and dispatch at the least expense . . . as may be practicable.” In re State Farm Lloyds, No. 15-903 (Tex. May 26, 2017).

Last Friday, the Texas Supreme Court denied mandamus relief in a high-profile dispute about the proper format in which to produce electronic records, but provided extensive guidance about the framework and factors that should decide such disputes, and remanded for reconsideration in light of that guidance. In a nutshell: “Under our discovery rules, neither party may dictate the form of electronic discovery. The requesting party must specify the desired form of production, but all discovery is subject to the proportionality overlay embedded in our discovery rules and inherent in the reasonableness standard to which our electronic-discovery rule is tethered. The taproot of this discovery dispute is whether production in native format is reasonable given the circumstances of this case. Reasonableness and its bedfellow, proportionality, require a case-by-case balancing of jurisprudential considerations,which is informed by factors the discovery rules identify as limiting the scope of discovery and geared toward the ultimate objective of “obtain[ing] a just,fair, equitable and impartial adjudication” for the litigants “with as great expedition and dispatch at the least expense . . . as may be practicable.” In re State Farm Lloyds, No. 15-903 (Tex. May 26, 2017).

The Texas Supreme Court’s newfound enthusiasm for mandamus review of orders granting motions for new trial after a jury trial (see, e.g., In re: United Scaffolding, 377 S.W.3d 685 (Tex. 2012)) has not been embraced by the courts of appeal (including Dallas) to orders setting aside a default judgment, or orders granting a new trial following a bench trial. A thorough summary of the Fifth Court’s opinions on those subjects appears in In re: Walker, No. 05-17-00404-CV (May 23, 2017) (mem. op.)

The Texas Supreme Court’s newfound enthusiasm for mandamus review of orders granting motions for new trial after a jury trial (see, e.g., In re: United Scaffolding, 377 S.W.3d 685 (Tex. 2012)) has not been embraced by the courts of appeal (including Dallas) to orders setting aside a default judgment, or orders granting a new trial following a bench trial. A thorough summary of the Fifth Court’s opinions on those subjects appears in In re: Walker, No. 05-17-00404-CV (May 23, 2017) (mem. op.)

New Local Rule 5, which became effective in May 2017, bridges a “gap” in the Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure about the briefing schedule when both parties have appealed.

The case of In re Bolt reminds when a party can seek mandamus relief to obtain a ruling on a motion. On the one hand, because “[m]andamus is appropriate to compel the performance of a ministerial duty,” it follows that “[a] trial jduge must consider and rule on a motion brought to the court’s attention within a reasonable amount of time, and a writ of mandamus may be issued to compel the trial court to rule in such instances.” But, as is required in other contexts where mandamus may be appropriate, the matter must be presented to the trial court: “To be properly filed and timely presented, a motion must be presentedd to a trial court at a time when the court has authority to act on the motion. The mere filing of a motion with the trial court clerk does not equate to a request that the trial court rule on the motion.” No. 05-17-00495-CV (May 22, 2017) (mem. op.)

The case of In re Bolt reminds when a party can seek mandamus relief to obtain a ruling on a motion. On the one hand, because “[m]andamus is appropriate to compel the performance of a ministerial duty,” it follows that “[a] trial jduge must consider and rule on a motion brought to the court’s attention within a reasonable amount of time, and a writ of mandamus may be issued to compel the trial court to rule in such instances.” But, as is required in other contexts where mandamus may be appropriate, the matter must be presented to the trial court: “To be properly filed and timely presented, a motion must be presentedd to a trial court at a time when the court has authority to act on the motion. The mere filing of a motion with the trial court clerk does not equate to a request that the trial court rule on the motion.” No. 05-17-00495-CV (May 22, 2017) (mem. op.)

Federal law, but highly relevant to the local corporate community – the Supreme Court’s unanimous May 22 decision in TC Heartland LLC v. Kraft Foods Group Brands LLC holds: “As applied to domestic corporations, ‘reside[nce]’ in [28 U.S.C.] § 1400(b) refers only to the State of incorporation.”

Emergency Medical Training Services sued Sheila Elliott for breaching various non-disclosure obligations in her complaints to state regulators. Elliott moved to dismiss under the Texas anti-SLAPP statute; the district court denied her motion, and the Fifth Court reversed and remanded for dismissal of the case in her favor.

Emergency Medical Training Services sued Sheila Elliott for breaching various non-disclosure obligations in her complaints to state regulators. Elliott moved to dismiss under the Texas anti-SLAPP statute; the district court denied her motion, and the Fifth Court reversed and remanded for dismissal of the case in her favor.

The Court used a standard two-step analysis. As to the first step, Elliott met her burden to show that EMTS’s claim was based on her exercise of free speech rights – a matter, the Court ruled, that was not affected by whether she had entered an NDA. As to the second step, EMTS failed to meet its burden to establish a prima facie case fo each element of its contract claim, as its evidence of damage was too conclusory. Elliott v. S&S Emergency Training Solutions, Inc., No. 05-16-01373-CV (May 16, 2017) (mem. op.)

In a quick break from Texas state practice – for a recent CLE presentation, I prepared the attached one-page chart to summarize the Fifth Circuit’s recent holdings about discovery.

The arbitration clause in Employee Solutions v. Wilkerson said, in part, that it applied to “. . . any and all claims challenging the existence, validity or enforceability of this [agreement] (in whole or in part) or challenging the applicability of this [agreement] to a particular dispute or claim.” To get around this broad language, the party opposing arbitration contended that it did not reach a “purely procedural” matter – the alleged failure to serve a written demand for arbitration on him and file it with the arbitral authority within the statute of limitations for negligence. The Fifth Court disagreed, noting the parties’ dispute as to whether this matter was a condition precedent to arbitration, which brought it squarely within the above language. No. 05-16-00283-CV (May 10, 2017) (mem. op.)

In the legal malpractice case of Ashton v. KoonsFuller, P.C., the Fifth Court affirmed a summary judgment for the defendant law firm. Among other issues addressed, the Court criticized the testimony of the plaintiff’s expert about the defendant’s billing, providing an illustration of the commonly-litigated Daubert/Robinson issue about whether an expert adequately considered alternatives to his or her conclusion: “[W]hile Hill disagrees with the amount of time KoonsFuller spent on discovery matters and preparing for mediation, the affidavit does not state how much time would have been reasonable. Similarly, Hill complains about the number of lawyers and legal assistants billing for those services, but does not suggest what an appropriate number would be.” No. 05-16-00130-CV (May 10, 2017) (mem. op.)

In the legal malpractice case of Ashton v. KoonsFuller, P.C., the Fifth Court affirmed a summary judgment for the defendant law firm. Among other issues addressed, the Court criticized the testimony of the plaintiff’s expert about the defendant’s billing, providing an illustration of the commonly-litigated Daubert/Robinson issue about whether an expert adequately considered alternatives to his or her conclusion: “[W]hile Hill disagrees with the amount of time KoonsFuller spent on discovery matters and preparing for mediation, the affidavit does not state how much time would have been reasonable. Similarly, Hill complains about the number of lawyers and legal assistants billing for those services, but does not suggest what an appropriate number would be.” No. 05-16-00130-CV (May 10, 2017) (mem. op.)

The new “permissive appeal” procedure has not led to a lot of permissive, interlocutory appeals; another example of that trend appears in Oklahoma Specialty Ins. Co. v. St. Martin de Porres, Inc. The parties stipulated to damages, the trial court found the policy ambiguous and thus interpreted in a certain way, and said it would follow whatever the Fifth Court decided about that interpretation. The Court declined to hear the case, finding: “Given the posture of this case following the trial court’s rulings and the parties’ stipulations, we conclude a permissive appeal will not materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation by considerably shortening the time, effort, and expense involved in obtaining a final judgment. (applying Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 51.014(d).

The new “permissive appeal” procedure has not led to a lot of permissive, interlocutory appeals; another example of that trend appears in Oklahoma Specialty Ins. Co. v. St. Martin de Porres, Inc. The parties stipulated to damages, the trial court found the policy ambiguous and thus interpreted in a certain way, and said it would follow whatever the Fifth Court decided about that interpretation. The Court declined to hear the case, finding: “Given the posture of this case following the trial court’s rulings and the parties’ stipulations, we conclude a permissive appeal will not materially advance the ultimate termination of the litigation by considerably shortening the time, effort, and expense involved in obtaining a final judgment. (applying Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code § 51.014(d).

I am speaking on the topic “Ethics 2017: Recent Federal Court Decisions to Know” on Friday, May 5, to the Plano Bar Association (noon at Palio’s Pizza, yum) – here is the PowerPoint that I will be using.

Plaintiff sued two insurance companies, headquartered out-of-state, who produced evidence that their business was limited to out-of-state activity. As to an allegation that the companies and their agents met in Toront o where they “conspired to forge [Plaintiff’s signature,” the Court reminded that “the assertion of personal jurisdiction over a nonresident defendant may not be based solely upon the effects or consequences of an alleged conspiracy with a resident in the forum state.” Friend v. Acadia Holding Corp., No. 05-16-00286-CV (April 27, 2017) (applying Nat’l Indus. Sand Ass’n v. Gibson, 897 S.W.2d 769, 773 (Tex. 1995)).

o where they “conspired to forge [Plaintiff’s signature,” the Court reminded that “the assertion of personal jurisdiction over a nonresident defendant may not be based solely upon the effects or consequences of an alleged conspiracy with a resident in the forum state.” Friend v. Acadia Holding Corp., No. 05-16-00286-CV (April 27, 2017) (applying Nat’l Indus. Sand Ass’n v. Gibson, 897 S.W.2d 769, 773 (Tex. 1995)).

Jones sued a TV production company, alleging that he was shot at and received death threats as a result of his appearance (even t hough blurred and voice-altered) on “The First 48,” a show about homicide investigations. The company did not prevail on its motion to dismiss based on the Texas anti-SLAPP statute: “The plain language of section 27.010(c) excludes legal actions seeking recovery for bodily injury. . . . Mr. Jones’s negligence claim seeks to recover for the bodily injuries—four gunshot wounds—that he claims he sustained as a result of Kirkstall’s negligence in editing and producing its program. Without expressing any opinion on the merits of his claim, we conclude that Mr. Jones has shown that it is exempted from application of the TCPA.” Kirkstall Road Enterprises v. Jones, No. 05-16-00859-CV (April 27, 2017).

hough blurred and voice-altered) on “The First 48,” a show about homicide investigations. The company did not prevail on its motion to dismiss based on the Texas anti-SLAPP statute: “The plain language of section 27.010(c) excludes legal actions seeking recovery for bodily injury. . . . Mr. Jones’s negligence claim seeks to recover for the bodily injuries—four gunshot wounds—that he claims he sustained as a result of Kirkstall’s negligence in editing and producing its program. Without expressing any opinion on the merits of his claim, we conclude that Mr. Jones has shown that it is exempted from application of the TCPA.” Kirkstall Road Enterprises v. Jones, No. 05-16-00859-CV (April 27, 2017).

The recent memorandum opinion in In re NCH Corp reminds of two basic points about mandamus practice.

The recent memorandum opinion in In re NCH Corp reminds of two basic points about mandamus practice.

- In a mandamus situation arising from the threatened disclosure of trade secrets: “No adequate appellate remedy exists if a trial court orders a party to produce privileged trade secrets absent a showing of necessity. In re Bass, 113 S.W.3d 735, 745 (Tex. 2003) (orig. proceeding) (citing In re Cont’l Gen. Tire, Inc., 979 S.W.2d 609, 615 (Tex. 1998) (orig. proceeding)). Further, a trial court abuses its discretion when it erroneously compels production of trade secrets without a showing that the information is ‘material and necessary.’ Id. at 738, 743.”

- The Fifth Court is using slightly revised “standard” language when denying mandamus relief in a short opinion: “To be entitled to mandamus relief, a relator must show both that the trial court has clearly abused its discretion and that relator has no adequate appellate remedy. In re Prudential Ins. Co., 148 S.W.3d 124, 135–36 (Tex. 2004) (orig. proceeding). . . . Based on the record before us, we conclude relator has not shown it is entitled to the relief requested. Accordingly, we DENY relator’s petition for writ of mandamus. See Tex. R. App. P. 52.8(a) (the court must deny the petition if the court determines relator is not entitled to the relief sought).

No. 05-17-00360-CV (Apr. 25, 2017) (mem. op.)

Smith intervened in a case after a judgment had been entered; the trial court granted a motion to strike his intervention. Resolving a tangled web of procedural issues, the Fifth Court held that (1) the striking of his intervention was not appealable before final judgment; (2) Smith’s appeal was limited to the merits of his intervention, not the claims of others; and (3) Smith’s filing of a motion for new trial extended the appellate deadlines. Smith v. City of Garland, No. 05-16-00454-CV (Apr. 20, 2017).

Smith intervened in a case after a judgment had been entered; the trial court granted a motion to strike his intervention. Resolving a tangled web of procedural issues, the Fifth Court held that (1) the striking of his intervention was not appealable before final judgment; (2) Smith’s appeal was limited to the merits of his intervention, not the claims of others; and (3) Smith’s filing of a motion for new trial extended the appellate deadlines. Smith v. City of Garland, No. 05-16-00454-CV (Apr. 20, 2017).

The Fifth Court reversed an award of lost profits in Radiant Financial, Inc. v. Bagby, which allegedly arose from improper customer solicitation about an insurance product, noting, inter alia: “Radiant admits the five policies [the expert] used in his estimate were not available at the time Radiant released the fifty-nine investors. Radiant argues that it had sufficient policies availale, but none of the investors chose to invest in those poliicies, even though Radiant presented those policies to its investors.” The Court concluded: “[T]o conclude the nineteen investors would have invested with Radiant instead of Paladin, we would be required to stack assumption upon assumption, which we will not do.” No. 05-16-00268-CV (April 18, 2017) (mem. op.)

The Fifth Court affirmed summary judgment for D Magazine in a defamation suit by a former volunteer, finding that most of the statements at issue were unactionable opinions or accurate statements of fact. Summarizing the underlying principles of free speech, the opinion reminds that a “rhetorical flourish” that is “merely unflattering, abusive, annoying, irksome, or embarrassing, or that only hurts the plaintiff’s feelings, is not actionable.” The court lacked appellate jurisdiction over part of a related appeal by the Dallas Symphony, since it involved the denial of a summary judgment about a tortious interference claim rather then free speech issues, although the Court was able to address the civil conspiracy claim against the Symphony. D Magazine Partners LP v. Reyes, No. 05-16-00294-CV (April 18, 2017) (mem. op.)

The Fifth Court affirmed summary judgment for D Magazine in a defamation suit by a former volunteer, finding that most of the statements at issue were unactionable opinions or accurate statements of fact. Summarizing the underlying principles of free speech, the opinion reminds that a “rhetorical flourish” that is “merely unflattering, abusive, annoying, irksome, or embarrassing, or that only hurts the plaintiff’s feelings, is not actionable.” The court lacked appellate jurisdiction over part of a related appeal by the Dallas Symphony, since it involved the denial of a summary judgment about a tortious interference claim rather then free speech issues, although the Court was able to address the civil conspiracy claim against the Symphony. D Magazine Partners LP v. Reyes, No. 05-16-00294-CV (April 18, 2017) (mem. op.)

Defendants sought review of a post-answer default judgment by restricted appeal. Unfortunately for them, “the record is silent regarding whether notice of the final hearing date was sent . . . . ” They thus failed to show error on the face of the record, as required in a restricted appeal, because “absence in the record of any proof that notice . . . was sent to a party is ‘just that–an absence of proof of error.” Odela Group LLC v. Double-R Walnut Management LLC, No. 05-16-00206-CV (April 12, 2017) (mem. op.) (applying and quoting Gold v. Gold, 145 S.W.3d 212 (Tex. 2004)).

AWD brought a flat tire to Logan & Son for repairs. Jaimes, who worked for Logan * Son, was injured while working on the tire, and contended that his employer, Logan & Son, was an independent contractor of AWD. The Fifth Court disagreed: “The evidence showed that AWD was simply a customer who did not have a right to control any aspect of Logan and Son’s work. When Jaimes was asked at his deposition what he was claiming AWD did to cause his injuries, he [only] said, ‘they brought the truck.'” Jaimes v. Lozano, No. 05-16-00165-CV (April 14, 2017) (mem. op.)

AWD brought a flat tire to Logan & Son for repairs. Jaimes, who worked for Logan * Son, was injured while working on the tire, and contended that his employer, Logan & Son, was an independent contractor of AWD. The Fifth Court disagreed: “The evidence showed that AWD was simply a customer who did not have a right to control any aspect of Logan and Son’s work. When Jaimes was asked at his deposition what he was claiming AWD did to cause his injuries, he [only] said, ‘they brought the truck.'” Jaimes v. Lozano, No. 05-16-00165-CV (April 14, 2017) (mem. op.)

In Viveri Youth Service v. Orme, the Fifth Court dismissed an appeal for lack of a final judgment. While the docket sheet indicated the case had been closed, the Court observed: “The last order, however, contains no language of finality or other indication the case was closed. While the trial court’s docket sheet reflects the case was closed, a docket sheet entry does not constitute a judgment or other appealable order of the trial court.” No. 05-17-00002-CV (April 11, 2017) (mem. op.)

A mandamus petition challenged an order allowing a “court-supervised winding up” of an LLC that owned over 700 acres of undeveloped land in Denton County. As to the procedural posture of the case, the Fifth Court obseved: “[M]andamus relief is proper to the extent the winding-up order permits execution before the entry of a final, appealable judgment.” On the merits, the court concluded that this order had that effect, “because if SRE is wound up and the property sold in the interim, [Petitioner]’s property rights and purported right to continue the business will be lost forever.” In re Spiritas, No. 05-16-00791-CV (Apr. 6, 2017) (mem. op.)

A mandamus petition challenged an order allowing a “court-supervised winding up” of an LLC that owned over 700 acres of undeveloped land in Denton County. As to the procedural posture of the case, the Fifth Court obseved: “[M]andamus relief is proper to the extent the winding-up order permits execution before the entry of a final, appealable judgment.” On the merits, the court concluded that this order had that effect, “because if SRE is wound up and the property sold in the interim, [Petitioner]’s property rights and purported right to continue the business will be lost forever.” In re Spiritas, No. 05-16-00791-CV (Apr. 6, 2017) (mem. op.)

The long-running dispute between the City of Dallas and the Topletz family, which owns a number of residential rental properties, reappeared in the case of Topletz v. City of Dallas. The Fifth Court substantially affirmed a temporary injunction in favor of the City and a class of tenants, reversing as to one provision that “prohibits appellants from raising rent, properly initiating eviction proceedings, or evicting . . . without leave of the trial court.” This provision was overly broad because it “enjoins activities the appellants otherwise have a legal right to perform . . . .” No. 05-16-00741-CV (April 6, 2017) (mem. op.) (citing, inter alia, Webb v. Glenbrook Owners Ass’n, Inc., 298 S.W.3d 374 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2009, no pet.)).

The long-running dispute between the City of Dallas and the Topletz family, which owns a number of residential rental properties, reappeared in the case of Topletz v. City of Dallas. The Fifth Court substantially affirmed a temporary injunction in favor of the City and a class of tenants, reversing as to one provision that “prohibits appellants from raising rent, properly initiating eviction proceedings, or evicting . . . without leave of the trial court.” This provision was overly broad because it “enjoins activities the appellants otherwise have a legal right to perform . . . .” No. 05-16-00741-CV (April 6, 2017) (mem. op.) (citing, inter alia, Webb v. Glenbrook Owners Ass’n, Inc., 298 S.W.3d 374 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2009, no pet.)).

The case of MacFarland v. Le-Vel Brands involved a blog post on the website “Lazy Man and Money,” which was critical of a multi-level marketing company that sells dietary supplements. The trial court denied the defendant’s motion to dismiss under the Texas anti-SLAPP statute and the Fifth Court reversed, finding: (1) the suit involved the blogger’s speech; (2) the “commercial speech” exception did not apply; and (3) the plain

The case of MacFarland v. Le-Vel Brands involved a blog post on the website “Lazy Man and Money,” which was critical of a multi-level marketing company that sells dietary supplements. The trial court denied the defendant’s motion to dismiss under the Texas anti-SLAPP statute and the Fifth Court reversed, finding: (1) the suit involved the blogger’s speech; (2) the “commercial speech” exception did not apply; and (3) the plain tiff could not establish damages for either business disparagement or defamation. (On that subject, compare the recent case from the Fifth Court of Glassdoor v. Andra Group, which did find sufficient evidence of damage.) The opinion carefully reviews the leading recent authorities on the scope of these provisions of the statute. The case was remanded for further proceedings, including consideration of the defendant’s attorneys’ fees and costs. No. 05-16-00672 (March 23, 2017) (mem. op.)

tiff could not establish damages for either business disparagement or defamation. (On that subject, compare the recent case from the Fifth Court of Glassdoor v. Andra Group, which did find sufficient evidence of damage.) The opinion carefully reviews the leading recent authorities on the scope of these provisions of the statute. The case was remanded for further proceedings, including consideration of the defendant’s attorneys’ fees and costs. No. 05-16-00672 (March 23, 2017) (mem. op.)

A law firm moved for summary judgment as to an unpaid balance, attaching an affidavit which in turn had several invoices attached. The Fifth Court reversed a summary judgment for the firm, noting that the affidavit did not (1) attach a complete set of invoices, (2) was missing entire pages, (3) only reflected that they were sent to one of the relevant parties, and (4) did not attach the computer records used to calculate the net balance. Thus, “[w]e conclude that without the invoices or computer records [the witness] relied on to support his affidavit, the affidavit was conclusory.” Acrey v. Kilgore & Kilgore PLLC, No. 05-15-01229-CV (March 30, 2017) (mem. op.)

Verveba Communications and a former employee, Jewell Thomas, settled a dispute about travel expenses after a JP court trial with this release: “each party hereby: (1) releases all claims against the other; (ii) waives his/its right to file a motion for new trial, [and] (iii) waives his/its right to appeal the [JP court] judgment . . . .” Jewell then brought new claims, beyond the contract claim litigated in JP court, and the Fifth Court affirmed their dismissal: “None of these cases [cited by Thomas] held that the release must identify each claim or cause of action by name to be effective and, in fact, none of the releases in these cases identified the claims being released specifically by name.” Thomas v. Verveba Telecom, LLC, No. 05-16-00123-CV (March 31, 2017) (mem. op.)

Verveba Communications and a former employee, Jewell Thomas, settled a dispute about travel expenses after a JP court trial with this release: “each party hereby: (1) releases all claims against the other; (ii) waives his/its right to file a motion for new trial, [and] (iii) waives his/its right to appeal the [JP court] judgment . . . .” Jewell then brought new claims, beyond the contract claim litigated in JP court, and the Fifth Court affirmed their dismissal: “None of these cases [cited by Thomas] held that the release must identify each claim or cause of action by name to be effective and, in fact, none of the releases in these cases identified the claims being released specifically by name.” Thomas v. Verveba Telecom, LLC, No. 05-16-00123-CV (March 31, 2017) (mem. op.)

An attorney paid a sanction and then challenged the sanctions order as part of the appeal from the final judgment in the action. In reviewing an objection based on mootness, the Fifth Court observed that while an appeal becomes moot “when a judgment debtor voluntarily pays and satisfied a judgment rendered against him,” the purpose of that rule is “to prevent appellants from misleading their opponents into believing a controversy is over when it is not.” Thus, “payment on a judgment will not moot an appeal of that judgment if the judgment debtor clearly expresses an intent that he intends to exercise his right of appeal and appellate relief is not futile.” Here, before the attorney paid the sanction, the other side had notice of his intent to appeal when payment was made, so the appeal was justiciable. Kamel v. AdvoCare Int’l, L.P., No. 05-16-00433-CV (March 28, 2017) (mem. op.)

An attorney paid a sanction and then challenged the sanctions order as part of the appeal from the final judgment in the action. In reviewing an objection based on mootness, the Fifth Court observed that while an appeal becomes moot “when a judgment debtor voluntarily pays and satisfied a judgment rendered against him,” the purpose of that rule is “to prevent appellants from misleading their opponents into believing a controversy is over when it is not.” Thus, “payment on a judgment will not moot an appeal of that judgment if the judgment debtor clearly expresses an intent that he intends to exercise his right of appeal and appellate relief is not futile.” Here, before the attorney paid the sanction, the other side had notice of his intent to appeal when payment was made, so the appeal was justiciable. Kamel v. AdvoCare Int’l, L.P., No. 05-16-00433-CV (March 28, 2017) (mem. op.)

In Glassdoor Inc. v. Andra Group LP, the Fifth Court affirmed an order granting a Rule 202 petition about online reviews of a business as an employer, offering several pointers for the handling of such petitions:

In Glassdoor Inc. v. Andra Group LP, the Fifth Court affirmed an order granting a Rule 202 petition about online reviews of a business as an employer, offering several pointers for the handling of such petitions:

- The trial judge limited the scope of the examination to two posts, and specific items within them;

- The movant established its potential business disparagement damages with three affidavits about the effect of the posts on its recruiting;

- The statements at issue went beyond “hyperbole or mere personal opinion” to make specific “accusations of illegal conduct that are capable of being proved true or false”; and

- The First Amendment rights of the anonymous reviewers to speak anonymously “must be balanced against the right of others to hold accountable those who engage in speech not protected by the First Amendment.”

A “mirror image” anti-SLAPP motion was properly rejected for the same reasons that the Rule 202 petition was granted. No. 05-16-00189-CV (March 24, 2017) (mem. op.)

If Dr. McCoy made his famous pronouncement, not as to an Enterprise crew member in a red shirt, but during litigation about another defendant by filing a “suggestion of death,” would he make a general appearance in that litigation? The Fifth Court answered “no” in Hegwer v. Edwards, primarily citing a line of cases holding that making and filing a Rule 11 agreement does not amount to a general appearance. No. 05-15-01464-CV (March 22, 2017).

If Dr. McCoy made his famous pronouncement, not as to an Enterprise crew member in a red shirt, but during litigation about another defendant by filing a “suggestion of death,” would he make a general appearance in that litigation? The Fifth Court answered “no” in Hegwer v. Edwards, primarily citing a line of cases holding that making and filing a Rule 11 agreement does not amount to a general appearance. No. 05-15-01464-CV (March 22, 2017).

“I-35 argues that, although the guaranty itself does not specify an interest rate, the guaranty incorporates the Note and the two must be read together. We agree.” Interstate 35-Chisam Road LP v. Moyaedi, No. 05-16-00196-CV (March 20, 2017) (mem. op.)

In D Magazine Partners LP v. Rosenthal, reviewing the work of the Dallas Court of Appeals in a high-profile anti-SLAPP case, the Texas Supreme Court observed about Wikipedia:

“Given the arguments both for and against reliance on Wikipedia, as well as the variety of ways in which the source may be utilized, a bright-line rule is untenable. Of the many concerns expressed about Wikipedia use, lack of reliability is paramount and may often preclude its use as a source of authority in opinions. At the least, we find it unlikely Wikipedia could suffice as the sole source of authority on an issue of any significance to a case. That said, Wikipedia can often be useful as a starting point for research purposes. In this case, for example, the cited Wikipedia page itself cited past newspaper and magazine articles that had used the term ‘welfare queen’ in various contexts and could help shed light on how a reasonable person could construe the term.”

But, as a matter of the relevant substantive law, and the nature of Wikipedia, t he Texas Supreme Court found overreliance on a Wikipedia entry when “the court of appeals utilized Wikipedia as its primary source to ascribe a specific, narrow definition to a single term that the court found significantly influenced the article’s gist. Essentially, the court used the Wikipedia definition as the lynchpin of its analysis on a critical issue. . . . ”

he Texas Supreme Court found overreliance on a Wikipedia entry when “the court of appeals utilized Wikipedia as its primary source to ascribe a specific, narrow definition to a single term that the court found significantly influenced the article’s gist. Essentially, the court used the Wikipedia definition as the lynchpin of its analysis on a critical issue. . . . ”

Accordingly, Dallas-area practitioners should pay special attention to these statements, if online resources such as Wikipedia play more than a general background role in a legal argument.

Echoing a line of cases from the Fifth Circuit about attorney immunity, and applying the Texas Supreme Court’s opinion in Cantey Hanger LLP v. Byrd, 467 S.W.3d 477 (Tex. 2015), the Fifth Court affirmed a summary judgment for a law firm involved in a foreclosure, noting: “The evidence shows Mackie Wolf provided appellants with a copy of the original note that appellants executed and all actions taken by Mackie Wolf were made in connection with its representation of its clients, BONY and Ocwen. The actions taken by Mackie Wolf that are the subject of this litigation—obtaining the note and presenting it to appellants—are the kinds of actions that are part of the discharge of an attorney’s duties in representing a party.” Santiago v. Mackie Wolf, No. 05-16-00394-CV (March 10, 2017) (mem. op.)

A useful reminder about timeliness appears in Duchouquette v. McWhorter, in which the appellant filed a late notice of appeal within the 15-day grace period, but neglected to move for leave to extend the deadline. In addition to dismissing the appellant’s appeal, the Fifth Court dismissed the cross-appeal noticed 8 days after the appellant’s: “[T]he Court does not have jurisdiction over a cross-appeal where the original notice of appeal is untimely.” No. 05-17-00041-CV (March 13, 2017) (mem. op.)

A useful reminder about timeliness appears in Duchouquette v. McWhorter, in which the appellant filed a late notice of appeal within the 15-day grace period, but neglected to move for leave to extend the deadline. In addition to dismissing the appellant’s appeal, the Fifth Court dismissed the cross-appeal noticed 8 days after the appellant’s: “[T]he Court does not have jurisdiction over a cross-appeal where the original notice of appeal is untimely.” No. 05-17-00041-CV (March 13, 2017) (mem. op.)

Together with Chrysta Castañeda, I recently wrote a short article for the State Bar Litigation Section about often-forgotten Texas Rules of Civil Procedure that can help keep legal issues alive at trial.

The writ of “scire facias” made one of its rare appearances in City of Dallas v. Ellis, after ten years passed from rendition of judgment, and the two-year grace period for a writ of scire facias expired as well. Unfortunately for the judgment debtor, under another provision of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code, the grace period does not expire for a judgment held by an incorporated city. The debtor did not persuade the Fifth Court that the city’s case should be viewed as one for subrogation that could potentially avoid that provision. No. 05-16-00348-CV (Feb. 17, 2017) (mem. op.)

The writ of “scire facias” made one of its rare appearances in City of Dallas v. Ellis, after ten years passed from rendition of judgment, and the two-year grace period for a writ of scire facias expired as well. Unfortunately for the judgment debtor, under another provision of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code, the grace period does not expire for a judgment held by an incorporated city. The debtor did not persuade the Fifth Court that the city’s case should be viewed as one for subrogation that could potentially avoid that provision. No. 05-16-00348-CV (Feb. 17, 2017) (mem. op.)

In Baxter & Associates, LLC v. D&D Elevators, Inc., No. 05-16-003300-CV (Feb. 15, 2017), the plaintiff appealed from the denial of a temporary injunction against former employees and the company they formed. The plaintiff alleged that the former employees took trade secrets, namely a list of builders with projects potentially including elevators, in violation of their fiduciary duties and the Texas Uniform Trade Secrets Act (“TUTSA”).

After a two-day hearing, the parties received a signed order denying the request for temporary injunction, which was attached to an email from the court administrator stating, “The Court makes the following rulings: … I do find that trade secret as to existing jobs or bids was obtained… [but] there is an adequate remedy at law….” The plaintiff requested findings of fact and conclusions of law, and filed a motion for reconsideration based on its argument that it did not need to show no adequate remedy at law under TUTSA to obtain injunctive relief. The trial court did not sign any findings of fact or conclusions of law, and the plaintiff appealed without filing a notice of past due findings and conclusions of law.

The first issue addressed by the court was procedural—whether the statement contained in the court administrator’s email stating the existence of trade secrets was a finding of fact. The Court of Appeals held it was not, in part because at a subsequent hearing the trial court stated that it had not made such a finding. Although the plaintiff formally requested findings of fact and conclusions of law, it failed to file a notice of past due findings and conclusions of law pursuant to Rule 297. Thus, the Court of Appeals held there were no findings of fact or conclusions of law, that any error for the failure to make such findings was not preserved, and implied a finding that the plaintiff had not shown the existence of a trade secret.

The Court went on to hold that there was evidence that would have allowed the trial court to conclude that the list of projects was not a trade secret because the information could be publicly identified, and therefore would not “derive[] independent economic value, actual or potential, from not being generally known….”

Baxter & Associates, LLC v. D&D Elevators, Inc., No. 05-16-003300-CV (Feb. 15, 2017)

vRide, a vanpool service, sought statutory indemnity from Ford after an accident, contending that the plaintiffs alleged – in substance – a products liability claim. The Fifth Court disagreed: The Cernoseks’ petition did not allege that the Ford van was unreasonably dangerous, was defective by manufacture or design, was rendered defective because it lacked certain safety features, or was otherwise defective. Instead, the petition alleged that vRide represented its vehicles had certain safety features when in actuality the vehicles did not have those safety features and that vRide failed to furnish vehicles with those safety features. In short, the Cernoseks’ petition did not contain allegations that the damages arose out of personal injury, death, or property damage allegedly caused by a defective product.” vRide v. Ford, No. 05-15-01377-CV (Feb. 2, 2017) (mem. op.)

vRide, a vanpool service, sought statutory indemnity from Ford after an accident, contending that the plaintiffs alleged – in substance – a products liability claim. The Fifth Court disagreed: The Cernoseks’ petition did not allege that the Ford van was unreasonably dangerous, was defective by manufacture or design, was rendered defective because it lacked certain safety features, or was otherwise defective. Instead, the petition alleged that vRide represented its vehicles had certain safety features when in actuality the vehicles did not have those safety features and that vRide failed to furnish vehicles with those safety features. In short, the Cernoseks’ petition did not contain allegations that the damages arose out of personal injury, death, or property damage allegedly caused by a defective product.” vRide v. Ford, No. 05-15-01377-CV (Feb. 2, 2017) (mem. op.)

The dispute that rolled into court in Wheel Technologies v. Gonzalez was whether a shipment of wheels had been delivered. The companies’ records were important but not dispositive, as the Fifth Court rounded up the facts: “This case essentially came down to a ‘he said, he said’ between two parties’ explanations of accounting. Blaser testified WTI always created a purchase order when it received a delivery and because WTI had no record of any outstanding purchase orders owed to Gonzalez, then it never received the tires. Gonzalez testified to the contrary. . . . Further, Blaser admitted he could not say for sure Owens always created a purchase order upon receipt of tires because Blaser was never personally involved in any of the transactions. Rather, Gonzalez testified there were many times in which the deliveries occurred after hours so checks and other documentation were not always ready when he made a delivery.” No. 05-16-00068-CV (Feb. 8, 2017) (mem. op.)

The dispute that rolled into court in Wheel Technologies v. Gonzalez was whether a shipment of wheels had been delivered. The companies’ records were important but not dispositive, as the Fifth Court rounded up the facts: “This case essentially came down to a ‘he said, he said’ between two parties’ explanations of accounting. Blaser testified WTI always created a purchase order when it received a delivery and because WTI had no record of any outstanding purchase orders owed to Gonzalez, then it never received the tires. Gonzalez testified to the contrary. . . . Further, Blaser admitted he could not say for sure Owens always created a purchase order upon receipt of tires because Blaser was never personally involved in any of the transactions. Rather, Gonzalez testified there were many times in which the deliveries occurred after hours so checks and other documentation were not always ready when he made a delivery.” No. 05-16-00068-CV (Feb. 8, 2017) (mem. op.)

In In re FPWP GP LLC, et al. (January 25, 2017), the Dallas Court of Appeals conditionally granted a writ of mandamus for the district court’s failure to transfer venue under the mandatory venue provision of Section 65.023 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code, which provides that “a writ of injunction against a party who is a resident of this state shall be tried in … the county in which the party is domiciled.” Courts have struggled at times to apply Section 65.023 because it does not apply to all suits seeking an injunction, but instead only to suits in which the relief requested is “purely or primarily injunctive.” So, if the primary form of relief is something else, e.g. damages, then the mandatory venue provision does not apply. The opinion gave examples of the exception, such as when injunctive relief is simply to maintain the status quo pending litigation or when there is no request for a permanent injunction. But in the case at hand, the plaintiff sought only a declaratory judgment that was effectively a mirror image of the permanent injunctive relief requested. Holding the injunction “was a means to the same end” as the declaratory judgment, the Court held that the primary purpose of the lawsuit was injunctive and that transfer to the county of domicile of the defendants was mandatory under Section 65.023.

When is a fraud claim subject to a 2-year limitations period? When it’s not a fraud claim.

January 25, 2017In Parsons v. Queenan, et al., No. 05-15-01375-CV (January 23, 2017), the Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed summary judgment in favor of the defendants on limitations grounds. The suit was Parsons’ third in a series of malpractice suits against different attorneys that represented him since the death of his wife in a plane crash more than two decades earlier.

The first issue was whether the breach of fiduciary duty and fraud claims were subject to a 2-year statute of limitations for negligence or a 4-year statute of limitations for fraud or breach of fiduciary duty. The Dallas Court held that the 2-year limitations period applied under the anti-fracturing rule, which prevents legal malpractice plaintiffs from “opportunistically transforming a claim that sounds only in negligence into other claims” to avail themselves of longer limitations periods, less onerous proof requirements, or other tactical advantages. For the anti-fracturing rule to apply, the gravamen of the complaint must focus on the quality or adequacy of the attorney’s representation. The Dallas Court concluded that the fraud and breach of fiduciary duty claims asserted by Parsons were claims for professional negligence as a matter of law.

In the second issue, the Dallas Court held that the 2-year limitations period began to run on the date of the denial of the motion for reconsideration by the Texas Supreme Court in the underlying litigation, not the date mandate was issued. Under Hughes v. Mahaney & Higgins, 821 S.W.2d 154 (Tex. 1991), “the statute of limitations on the malpractice claim against the attorney is tolled until all appeals on the underlying claim are exhausted.” Id. at 157. The Dallas Court held that appeals are exhausted when a motion for rehearing with the Texas Supreme Court is denied because that is the last action of right that can be taken in the underlying case.

Parsons v. Queenan, et al., No. 05-15-01375-CV (January 23, 2017)

Appeals from forcible entry and detainer actions are common and we do not ordinarily report on them, but it has been some time since we last noted a summary of key principles. A good one appears in the recent case of McCall v. Fannie Mae, in which the appellant alleged improprieties about the relevant foreclosure sale. “But,” noted the Fifth Court, “the deed of trust expressly created a landlord and tenant-at-sufferance relationship when the property was sold by foreclosure. This provided an independent basis to determine the issue of immediate possession without resolving the issue of title. As we have explained, any defects in the foreclosure process . . . may be pursued in a suit for wrongful foreclosure or to set aside the substitute trustee’s deed, but they are not relevant in this forcible detainer action.” No. 05-16-00010-CV (Jan. 20, 2017) (mem. op.)

Appeals from forcible entry and detainer actions are common and we do not ordinarily report on them, but it has been some time since we last noted a summary of key principles. A good one appears in the recent case of McCall v. Fannie Mae, in which the appellant alleged improprieties about the relevant foreclosure sale. “But,” noted the Fifth Court, “the deed of trust expressly created a landlord and tenant-at-sufferance relationship when the property was sold by foreclosure. This provided an independent basis to determine the issue of immediate possession without resolving the issue of title. As we have explained, any defects in the foreclosure process . . . may be pursued in a suit for wrongful foreclosure or to set aside the substitute trustee’s deed, but they are not relevant in this forcible detainer action.” No. 05-16-00010-CV (Jan. 20, 2017) (mem. op.)

Claims to stop payment to Paxton prosecutors moot and still not ripe—no jurisdiction.

January 19, 2017The Dallas Court of Appeals was pulled into one of the wide-ranging disputes concerning the prosecution of Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton, this one concerning the payment of private attorneys appointed to prosecute Paxton. The Dallas Court determined that it lacked jurisdiction because the claims were moot and were not yet ripe.

Attorneys were appointed to prosecute Paxton after the Collin County Criminal District Attorney recused his office. The appointed attorneys were to be paid $300 per hour, which was more than fixed $1000 for most court appointed attorneys for indigent defendants under the Collin County local rules, which also apply to appointed prosecutors. However, the local rules also provided “Payment can vary from the fee schedule in unusual circumstances or where the fee would be manifestly inappropriate because of circumstances beyond the control of the appointed counsel.”

On December 11, 2015, the appointed prosecutors sought an interim payment of $254,908.85 from Collin County. Three weeks later, Collin County taxpayer Jeffory Blackard sued seeking a temporary restraining order and injunction preventing payment, asserting that as a taxpayer he had standing to seek to enforce the local rules fixing most fees at a flat $1000. The Collin County judge recused himself, and the taxpayer suit was assigned to County Court at Law No. 5 in Dallas County.

A week after Blackard filed his taxpayer suit, the presiding judge over the criminal prosecution, a Tarrant County judge, approved the payment of the request for interim fees and ordered that the fees be presented to the Collin County Commissioner’s Court for payment. The next day, Blackard filed a supplemental application for temporary restraining order in the Dallas County taxpayer suit, which was denied one day later. Three days after that, only one month after the initial request for interim fees was made, the Collin County Commissioners Court voted to pay. Blackard then filed an amended petition seeking injunctive relief preventing any future requests for attorney’s fees by the appointed prosecutors. The County Court at Law determined that it lacked jurisdiction and granted the defendants’ pleas to the jurisdiction. Blackard appealed.

The Dallas Court began its analysis by noting that mootness and ripeness are threshold issues that implicate subject matter jurisdiction. Rendering opinions under either circumstance violates the prohibition against rendering advisory opinions because such cases present no justiciable controversy.

The Dallas Court held that Blackard’s claims relating to the interim fees were moot because the fees had already been paid and, under Texas law, taxpayers have standing only to seek to enjoin future payments, not to recover funds that have already been paid. Blackard asserted on appeal that his claims fell within the exception to mootness for claims “capable of repetition, yet evading review” because the appointed attorneys stipulated that they anticipated submitting future invoices. But the Dallas Court rejected that exception, which “applies only in rare circumstances.” It noted that the exception had previously only been used to challenge unconstitutional acts performed by the government, and held that the process by which fees would be requested in the future provided sufficient time for Blackard to seek judicial review prior to payment, pointing to the month between the initial request for interim fees and payment.

In addition, the Dallas Court held that claims relating to future invoices were not yet ripe. While it was stipulated that additional fees would be requested, it was not stipulated that the additional requests would be for $300 an hour or otherwise would be inconsistent with the Collin County fee schedule. So the Dallas Court concluded there was no live controversy concerning future requests for fees.

In the common fact situation of an employee leaving for a new, competing employer, the Fifth Court found no abuse of discretion in denying a temporary injunction when:

- After his termination, Turner did not have access to any confidential information except for the contents of a laptop

- Turner testified that he did not access the laptop following his termination except to examine his girlfriend’s resume and his employment agreement and when he took it to the Apple Store to have his personal photographs removed from the computer.

- Plaintiff had a forensic examination of the computer performed, and it presented no evidence that Turner’s testimony was false.

- When Turner also testified that when he went to work for Gulfstream, he did not contact any of BM Medical’s clients with whom he had worked while employed by BM Medical (although some contacted him to find out what had happened to him); and

- Only one client of BM Medical became a client of Gulfstream, who was a good friend of Turner’s whom Turner had known before he went to work for BM Medical, and who still did business with BM Medical.

BM Medical Management Service LLC v. Turner, No. 05-16-00670-CV (Jan. 10, 2017) (mem. op.)

The first ever Bench-Bar conference for the Northern District of Texas will be held on January 27 at the Four Seasons in Las Colinas. Here is the schedule and registration information; it looks to be a great program and the beginning of a strong tradition.

The first ever Bench-Bar conference for the Northern District of Texas will be held on January 27 at the Four Seasons in Las Colinas. Here is the schedule and registration information; it looks to be a great program and the beginning of a strong tradition.

Governor Abbott has appointed Dallas attorney Jason Boatright to the vacancy on the Fifth Court; more information is available in the official press release.

Governor Abbott has appointed Dallas attorney Jason Boatright to the vacancy on the Fifth Court; more information is available in the official press release.

Enxeco Inc. v. Staley reversed a dismissal for want of prosecution, observing: “[T]he rules of judicial administration provide that civil non-jury cases should be brought to trial or final disposition within twelve months from the defendant’s appearance date. The administrative rules expressly recognize, however, that in complex cases or special circumstances ‘it may not be possible to adhere to these standards.'” (citations omitted). Here, such circumstances were presented by lengthy motion practice about forum and capacity issues. The Court gave little weight to plaintiff’s decision to not pursue discovery, noting that no rule compelled it to do so. No. 05-15-01047-CV (Jan. 9, 2017) (mem. op.)

Heath’s employment agreement incorporated a confidentiality agreement, which in turn required arbitration of “any controversy, dispute or claim arising out of or in any way related to or involving the interpretation, performance or breach of this Agreement . . .” The Fifth Court noted that phrases such as “any controversy” are viewed, by federal and state courts, as “broad arbitration clauses capable of expansive reach.” It rejected the argument that the term “this Agreement” referred only to the confidentiality agreement, even though that agreement had a merger clause, because the arbitration clause refers to both claims “arising out of” and “in any way related to” the agreement. The Court also noted that the employment and confidentiality agreement were executed at the same time, and that its holding would apply fully to Heath’s tort claims as well. Advocare GP LLC v. Heath, No. 05-16-0049-CV (Jan. 5, 2017) (mem. op.)

Heath’s employment agreement incorporated a confidentiality agreement, which in turn required arbitration of “any controversy, dispute or claim arising out of or in any way related to or involving the interpretation, performance or breach of this Agreement . . .” The Fifth Court noted that phrases such as “any controversy” are viewed, by federal and state courts, as “broad arbitration clauses capable of expansive reach.” It rejected the argument that the term “this Agreement” referred only to the confidentiality agreement, even though that agreement had a merger clause, because the arbitration clause refers to both claims “arising out of” and “in any way related to” the agreement. The Court also noted that the employment and confidentiality agreement were executed at the same time, and that its holding would apply fully to Heath’s tort claims as well. Advocare GP LLC v. Heath, No. 05-16-0049-CV (Jan. 5, 2017) (mem. op.)

The trial court granted summary judgment for the employer (oddly enough, a labor union) in a dispute arising from an employee’s benefits. The Fifth Court reversed, finding ambiguity in the underlying disability policy (noting, in particular, its interplay with separately-drafted legal instruments about the employment relationship – a recurring issue in disputes about arbitration clauses), and also finding related fact issues about whether the contract was unilateral or bilateral, and whether the employee had exhausted administrative remedies. The opinion recaps the major authorities about the role of contractual ambiguity in a summary judgment analysis. Videtich v. Transport Workers Union of Am., No. 05-15-01449-CV (Dec. 29, 2016) (mem. op.)

Nations Renovations successfullly sued Hong in quantum meruit for unpaid construction work, and successfully defended against misrepresentation claims. The Fifth Court affirmed based on contract terms. As to the quantum meruit claim, it noted: “Because the four items [at issue] are listed only as recommendations and the other items of Extra Work claimed by Nations are not mentioned in the Contract, we conclude the Extra Work is not covered by the Contract. Therefore, the trial court properly submitted the quantum meruit question to the jury.” As to the misrepresentation claims, applying Italian Cowboy, the Court found this disclaimer of reliance to be effective: “17. ANY REPRESENTATIONS, STATEMENTS, OR OTHER COMMUNICATIONS NOT WRITTEN ON THIS CONTRACT ARE AGREED TO BE IMMATERIAL and not relied on by either party and do not survive the execution of this contract.” Hong v. Nations Renovations LLC, No. 05-15-01036-CV (Dec. 29, 2016) (mem. op.)

Nations Renovations successfullly sued Hong in quantum meruit for unpaid construction work, and successfully defended against misrepresentation claims. The Fifth Court affirmed based on contract terms. As to the quantum meruit claim, it noted: “Because the four items [at issue] are listed only as recommendations and the other items of Extra Work claimed by Nations are not mentioned in the Contract, we conclude the Extra Work is not covered by the Contract. Therefore, the trial court properly submitted the quantum meruit question to the jury.” As to the misrepresentation claims, applying Italian Cowboy, the Court found this disclaimer of reliance to be effective: “17. ANY REPRESENTATIONS, STATEMENTS, OR OTHER COMMUNICATIONS NOT WRITTEN ON THIS CONTRACT ARE AGREED TO BE IMMATERIAL and not relied on by either party and do not survive the execution of this contract.” Hong v. Nations Renovations LLC, No. 05-15-01036-CV (Dec. 29, 2016) (mem. op.)

In Heritage Numismatic Auctions v. Stiel, a dispute about the the sale of rare coins, the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a motion to compel arbitration, finding that the relevant documents were not adequately proved up by the sponsoring affidavit. The witness “did not testify that the documents in Exhibit F were ‘true and correct’ copies of the contracts or otherwise state that they were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals.” While the affidavit began with the phrase, “The facts contained herein are true and correct,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could interpret this statement as asserting the factual averments in the affidavit were true and correct but not asserting the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals as required by Rule 902(10)(B)(2).” Finally, from a general description of the documents as “the various Terms and Conditions . . . ,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could have concluded that [the witness’s] statement did not constitute testimony that the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact copies of the contracts.” No. 05-16-00299-CV (Dec. 16, 2016) (mem. op.)

In Heritage Numismatic Auctions v. Stiel, a dispute about the the sale of rare coins, the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a motion to compel arbitration, finding that the relevant documents were not adequately proved up by the sponsoring affidavit. The witness “did not testify that the documents in Exhibit F were ‘true and correct’ copies of the contracts or otherwise state that they were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals.” While the affidavit began with the phrase, “The facts contained herein are true and correct,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could interpret this statement as asserting the factual averments in the affidavit were true and correct but not asserting the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact duplicates of the originals as required by Rule 902(10)(B)(2).” Finally, from a general description of the documents as “the various Terms and Conditions . . . ,” the Court held that “[t]he trial court could have concluded that [the witness’s] statement did not constitute testimony that the documents in Exhibit F were the originals or exact copies of the contracts.” No. 05-16-00299-CV (Dec. 16, 2016) (mem. op.)

In a technical but financially critical decision, Eddington v. Dallas Police & Fire Pension System, the Fifth Court held that adjustments to the future interest rate paid on accounts established under a pension plan, sponsored by the beleaguered Dallas Police & Fire Pension system, did not violate the prohibition on benefit reductions contained in article XVI, section 66 of the Texas Constitution. No. 05-15-00839-CV (Dec. 13, 2016). Of general interest, a component of its analysis reviewed when a federal Fifth Circuit opinion about state law matters will be followed in state court.

In a technical but financially critical decision, Eddington v. Dallas Police & Fire Pension System, the Fifth Court held that adjustments to the future interest rate paid on accounts established under a pension plan, sponsored by the beleaguered Dallas Police & Fire Pension system, did not violate the prohibition on benefit reductions contained in article XVI, section 66 of the Texas Constitution. No. 05-15-00839-CV (Dec. 13, 2016). Of general interest, a component of its analysis reviewed when a federal Fifth Circuit opinion about state law matters will be followed in state court.

Yes, it arose in the unusu

Yes, it arose in the unusu al procedural posture of a Rule 736 home equity loan foreclosure, and no, it is not the recommended practice. That said, the relators in the case of In re:

al procedural posture of a Rule 736 home equity loan foreclosure, and no, it is not the recommended practice. That said, the relators in the case of In re:  Priester successfully convinced the Fifth Court to reverse direction and, on rehearing, grant a writ of mandamus in their favor “[i]n light of the more developed record and clarified arguments . . . .” No. 05-16-00965-CV (Nov. 21, 2016) (mem. op.)

Priester successfully convinced the Fifth Court to reverse direction and, on rehearing, grant a writ of mandamus in their favor “[i]n light of the more developed record and clarified arguments . . . .” No. 05-16-00965-CV (Nov. 21, 2016) (mem. op.)

While affirming a relatively straightforward judgment in a home loan dispute, the Fifth Court observed: “The unjust enrichment doctrine applies principles of restitution to disputes where there is no actual contract and is based on the equitable principle that one who receives benefits which would be unjust for him to retain ought to make restitution.” Ihde v. First Horizon Home Loans, No. 05-15-01084-CV (Nov. 28, 2016) (mem. op.) (emphasis added) A counterpoint in this practical but rarely-visited area of remedies law appears in City of Harker Heights v. Sun Meadows Land Ltd., 830 S.W.2d 313, 317 (Tex. App.–Austin 1992, no writ), which observes: “An action for money had and received may be founded upon an express agreement or one implied in fact, but it is not dependent upon either.” (emphasis added).

While affirming a relatively straightforward judgment in a home loan dispute, the Fifth Court observed: “The unjust enrichment doctrine applies principles of restitution to disputes where there is no actual contract and is based on the equitable principle that one who receives benefits which would be unjust for him to retain ought to make restitution.” Ihde v. First Horizon Home Loans, No. 05-15-01084-CV (Nov. 28, 2016) (mem. op.) (emphasis added) A counterpoint in this practical but rarely-visited area of remedies law appears in City of Harker Heights v. Sun Meadows Land Ltd., 830 S.W.2d 313, 317 (Tex. App.–Austin 1992, no writ), which observes: “An action for money had and received may be founded upon an express agreement or one implied in fact, but it is not dependent upon either.” (emphasis added).

I was on the trial team that won a $146 million verdict in Pecos, Texas last week; here is the Dallas Morning News’s recent story on the case.

I was on the trial team that won a $146 million verdict in Pecos, Texas last week; here is the Dallas Morning News’s recent story on the case.

Plaintiffs won a lawsuit against their landlord about the handling of their security deposit. The Fifth Court affirmed, reversing only as to prejudgment interest. While the parties’ lease said that “[a]ny person who is a prevailing party in any legal proceeding brought under or related to the transaction described in this lease is entitled to recover prejudgment interest,” the plaintiffs recovered based on section 92.109(a) of the Property Code, which allows recovery of statutory penalties in the event of a landlord’s bad faith retention of the security deposit. Because “[p]rejudgment interest does not apply to statutory penalties imposed for wrongdoing,” and the underlying statute did not provide for recovery of prejudgment interest, the interest award could not stand. Frazin v. Sauty, No. 05-15-00879-CV (Nov. 6, 2016) (mem. op.)

Plaintiffs won a lawsuit against their landlord about the handling of their security deposit. The Fifth Court affirmed, reversing only as to prejudgment interest. While the parties’ lease said that “[a]ny person who is a prevailing party in any legal proceeding brought under or related to the transaction described in this lease is entitled to recover prejudgment interest,” the plaintiffs recovered based on section 92.109(a) of the Property Code, which allows recovery of statutory penalties in the event of a landlord’s bad faith retention of the security deposit. Because “[p]rejudgment interest does not apply to statutory penalties imposed for wrongdoing,” and the underlying statute did not provide for recovery of prejudgment interest, the interest award could not stand. Frazin v. Sauty, No. 05-15-00879-CV (Nov. 6, 2016) (mem. op.)

The first rule of confidential settlements is: we don’t talk about confidential settlements

November 4, 2016GDL Masonry Supply, Inc. v Lopez and Rapid Masonry Supply, Inc. (November 2, 2016) is a handy opinion to hand your clients after they sign a settlement agreement requiring confidentiality. It is a risk too many clients do not take seriously enough (see, e.g., “Girl costs father $80,000 with ‘SUCK IT’ Facebook post“).

In GDL, the Dallas Court of Appeals affirmed summary judgment in favor of Rapid, the plaintiff, who refused to pay under a settlement agreement because GDL failed to satisfy the confidentiality requirements of the agreement. The facts were too common. GDL brought suit against Rapid, which settled by way of an agreement that required confidentiality and Rapid to make a series of $10,000 payments totaling $60,000 to GDL. GDL then told a third party that Rapid had stolen from it, that GDL won the lawsuit, and that Rapid owed GDL money as a result. When Rapid discovered what GDL said about their litigation, it sued asserting that it had no obligation to make the remaining settlement payments and also seeking attorney’s fees for breach of the confidentiality language. The trial court granted summary judgment to Rapid, holding that the confidentiality provision was breached, that Rapid had no obligation to make further payments, and awarding attorney’s fees.

GDL’s argument on appeal did not deny the disclosure of the settlement, but instead challenged the materiality of the confidentiality provision. The Dallas Court of Appeals made swift work in rejecting this argument, noting that the settlement agreement itself stated that the confidentiality paragraph “is a material provision of this Agreement and that any breach of the terms and conditions of [the paragraph] shall be a material breach of this Agreement.” The Court held that the contract’s language was binding.

GDL Masonry Supply, Inc. v Lopez and Rapid Masonry Supply, Inc.

From sister blog 600Camp – celebrate Halloween with these Five Recent Fifth Circuit Cases to Know. And don’t forget to vote for Super Lawyers by this Friday, October 28!

A classic example of a “too soon” appeal appears in Bolden v. Fidelity Nat’l Title: “In the original petition, appellee sought both damages for breach of warranty of title and attorney’s fees. The trial court signed a default judgment awarding damages for