Ali v. DSA Partners provides a useful reminder about a common situation in multi-party litigation: “[A]s a general rule, severance after an interlocutory summary-judgment order to expedite appellate review is proper and not an abuse of discretion.” No. 05-18-01240-CV (March 24, 2020) (mem. op.).

Ali v. DSA Partners provides a useful reminder about a common situation in multi-party litigation: “[A]s a general rule, severance after an interlocutory summary-judgment order to expedite appellate review is proper and not an abuse of discretion.” No. 05-18-01240-CV (March 24, 2020) (mem. op.).

Monthly Archives: March 2020

The appellants in Trubenbach v. Energy Exploration “urge[d] that ‘context matters.’ They argue that as non-signatories, they can compel Energy Exploration to arbitration but Energy Exploration cannot compel them to arbitration. But this is not a case in which non-signatories first moved to compel arbitration, then later changed their minds, withdrew their consent, and proceeded with the litigation in a judicial forum. Here, appellants urged diametrically opposing positions in two different courts at the same time.” (emphasis in original).

The appellants in Trubenbach v. Energy Exploration “urge[d] that ‘context matters.’ They argue that as non-signatories, they can compel Energy Exploration to arbitration but Energy Exploration cannot compel them to arbitration. But this is not a case in which non-signatories first moved to compel arbitration, then later changed their minds, withdrew their consent, and proceeded with the litigation in a judicial forum. Here, appellants urged diametrically opposing positions in two different courts at the same time.” (emphasis in original).

As a result, “[t]heir conduct in claiming rights under the arbitration agreement and their conduct throughout the course of this proceeding clearly reflected their willingness to forego their right to a judicial forum.” No. 05-18-01090-CV (March 27, 2020) (mem. op.). The Court also observed: “Appellants’ actions are akin to behavior prohibited by the invited error doctrine—a party may not complain of an error which the party invited.” (citations omitted).

The business fallout from the failed bus-camera program at the now-defunct Dallas County Schools (“DCS”) led to litigation about the related intellectual property, which led to a TCPA motion filed by a bidder on the technology during the winding up of DCS. The Fifth Court found that the (pre-September-2019) TCPA did not apply, emphasizing its free-speech prong but also finding no protected right of association or petition:

The business fallout from the failed bus-camera program at the now-defunct Dallas County Schools (“DCS”) led to litigation about the related intellectual property, which led to a TCPA motion filed by a bidder on the technology during the winding up of DCS. The Fifth Court found that the (pre-September-2019) TCPA did not apply, emphasizing its free-speech prong but also finding no protected right of association or petition:

Although the BusStop Technology provides safety measures for children who ride school buses, the benefits of the technology were not the basis of the communications. ATS’s communications with DCS and the Dissolution Committee, including requesting and receiving information about the technology, obtaining prototypes of the technology, and ATS’s actual bid, were private communications about a private, commercial transaction. Similarly, although DCS and the Dissolution Committee are governmental entities, the transactions and associated communications were private financial transactions that did not impact the public; the transactions did not require public approval, and ATS did not argue that the governmental status of DCS and the Dissolution Committee brought the communications into the realm of public concern.

BusPatrol America LLC v. American Traffic Solutions, Inc., No. 05-18-00920-CV (March 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

The key issue in Hernandez v. Sun Crane & Hoist, Inc. was whether a general contractor exercised “actual control” over a subcontractor’s work. The en banc court reversed a no-evidence summary judgment for the contractor, observing in footnote 9:

“. . . The original panel’s analysis omits any mention of (1) the Subcontract provisions described above regarding schedule control and mandatory safety harness use; (2) Johnston’s testimony that JLB supervisory employees were on-site on the day of the accident and knew the cage could fall over in the event of strong wind or improper bracing; (3) Hernandez’s testimony that he saw JLB supervisors looking at the cage’s bracing prior to the accident; and (4) Molina’s statements that the wind speed was 15–25 miles per hour on the day of the accident and Hernandez was told to jump, but was tethered to the cage by his safety harness.

Those omissions demonstrate that the original panel’s opinion represents a serious departure from precedent in the review of no-evidence summary judgment cases and therefore warrants en banc review under Texas Rule of Appellate Procedure 41.2 to ‘secure or maintain uniformity of the court’s decisions.'”

The court split cleanly along party lines, with all Democratic justices joining the majority opinion, and all Republican justices joining two dissents. Justice Bridges disagreed with the majority’s legal analysis while Justice Whitehill questioned whether the case had warranted en banc consideration. No. 05-17-00719-CV (March 26, 2020).

The estate of Billy Dickson alleged that he died from asbestos exposure at a Bell Helicopter plant. The estate won at trial on a theory of gross negligence. The panel reversed on legal sufficiency grounds, finding no evidence that Bell subjectively knew of a risk to Dickson based on his use of boards containing asbestos as part of the testing of helicopter components. Bell Helicopter Textron v. Dickson, No. 05-17-00979-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.) Justice Bridges wrote the opinion, joined by Justice Whitehill and then-Justice Brown.

The full court denied en banc review on March 25. Justice Bridges signed the order, apparently joined by Justices Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, Pedersen, and Evans. Justices Molberg and Nowell did not participate.

The full court denied en banc review on March 25. Justice Bridges signed the order, apparently joined by Justices Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, Pedersen, and Evans. Justices Molberg and Nowell did not participate.

A dissent criticized the panel’s application of the City of Keller standard as not properly considering all the evidence heard by the jury, and noted : “This court has misapplied the legal sufficiency standard of review to second-guess jury verdicts before and here, it does so again.” Justice Carlyle wrote the opinion, joined by Chief Justice Burns and Justices Osborne, Partida-Kipness, and Reichek.

A concurrence, written by Justice Whitehill and joined by all other Republican Justices on the Court (Justices Bridges, Myers, Schenck, and Evans), responded to the dissent, noting inter alia: “With no apparent bearing on the correct legal analysis of the issues in this case, the dissenting opinion (i) criticizes four prior opinions from this Court that are not asbestos cases and have no apparent logical relationship to this case . . . ”

A concurrence, written by Justice Whitehill and joined by all other Republican Justices on the Court (Justices Bridges, Myers, Schenck, and Evans), responded to the dissent, noting inter alia: “With no apparent bearing on the correct legal analysis of the issues in this case, the dissenting opinion (i) criticizes four prior opinions from this Court that are not asbestos cases and have no apparent logical relationship to this case . . . ”

To summarize, the vote was 6-5 against en banc review, largely on party lines, and would have come out differently had the two nonparticipating Justices joined their Democratic colleagues.

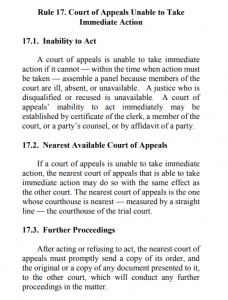

The coronavirus situation has prompted review of once-obscure statutes and rules; among them, Tex. R. App. 17, which addresses where to go if the ordinarily-assigned court of appeals is unavailable. Surprisingly, Rule 17.2 sends the relevant party to the nearest alternative court of appeals, measured by distance from the trial court. For courts in the Dallas district, then, that could be Fort Worth, Waco, Tyler, or Texarkana. (To be clear, THE DALLAS COURT IS AVAILABLE, this post is just a note on a TRAP that has become less obscure in light of current events.)

The coronavirus situation has prompted review of once-obscure statutes and rules; among them, Tex. R. App. 17, which addresses where to go if the ordinarily-assigned court of appeals is unavailable. Surprisingly, Rule 17.2 sends the relevant party to the nearest alternative court of appeals, measured by distance from the trial court. For courts in the Dallas district, then, that could be Fort Worth, Waco, Tyler, or Texarkana. (To be clear, THE DALLAS COURT IS AVAILABLE, this post is just a note on a TRAP that has become less obscure in light of current events.)

While mandamus litigation often focuses on whether a clear abuse of discretion occurred, the other relevant factors can also be dispositive. Consider the panel majority in In re Alpha-Barnes Real Estate Services LLC, which observed: “While the trial court’s order presents an error potentially justifying reversal on a direct appeal, has failed to demonstrate the inadequacy of an appeal, particularly given the limited scope of the order and alternative mechanisms by which relator may introduce the same evidence excluded by the order.” It also relied upon laches, noting a lengthy and unexplained delay in seeking mandamus relief. A dissent would have granted the petition, noting the likely effect on the trial, and that the parties had entered a stipulation about the otherwise-unexplained delay. No. 05-20-00073-CV (March 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

While mandamus litigation often focuses on whether a clear abuse of discretion occurred, the other relevant factors can also be dispositive. Consider the panel majority in In re Alpha-Barnes Real Estate Services LLC, which observed: “While the trial court’s order presents an error potentially justifying reversal on a direct appeal, has failed to demonstrate the inadequacy of an appeal, particularly given the limited scope of the order and alternative mechanisms by which relator may introduce the same evidence excluded by the order.” It also relied upon laches, noting a lengthy and unexplained delay in seeking mandamus relief. A dissent would have granted the petition, noting the likely effect on the trial, and that the parties had entered a stipulation about the otherwise-unexplained delay. No. 05-20-00073-CV (March 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

- the performance issue was a basic assumption of the contract;

- the government’s action was an official order or regulation (in that case, the SEC’s contact with the defendant was not); and

- the defendant was acting in good faith.

The Court relied on an earlier Texas Supreme Court case and the relevant Restatement (Second) of Contracts provision. Application of this opinion will be important in upcoming commercial disputes created by the novel coronavirus.

This is a cross-post from 600Hemphill, which follows the Texas Supreme Court:

This is a cross-post from 600Hemphill, which follows the Texas Supreme Court:

Henry McCall lived in a cabin on Homer Hillis’s property, occasionally helping Hillis with maintenance at the McCall’s bed-and-breakfast. While working on Hillis’s sink, a brown recluse spider bit McCall. The Texas Supreme Court found that the ferae naturae doctrine barred McCall’s lawsuit against  Hillis: “[H]e owed no duty to the invitee because he was unaware of the presence of brown recluse spiders on his property and he neither attracted the offending spider to his property nor reduced it to his possession. Further, [McCall] had actual knowledge of the presence of spiders on the property.” Hillis v. McCall, No. 18-1065 (Tex. March 13, 2020). In addition to its impact on brown-recluse litigation, the reasoning of this opinion about liability for small, dangerous creatures well be relevant in any future litigation about coronavirus exposure.

Hillis: “[H]e owed no duty to the invitee because he was unaware of the presence of brown recluse spiders on his property and he neither attracted the offending spider to his property nor reduced it to his possession. Further, [McCall] had actual knowledge of the presence of spiders on the property.” Hillis v. McCall, No. 18-1065 (Tex. March 13, 2020). In addition to its impact on brown-recluse litigation, the reasoning of this opinion about liability for small, dangerous creatures well be relevant in any future litigation about coronavirus exposure.

In re Johnson catches the eye as an atypical non-memorandum opinion in a pro se mandamus proceeding arising from a criminal case. The novel feature of the opinion is its footnote (longer than the actual opinion), using the Court’s “discretion to take judicial notice of adjudicative facts that are matters of public record” to review the relevant online docket sheet to establish mootness. No. 05-20-00068-CV (March 11, 2020)

In re Johnson catches the eye as an atypical non-memorandum opinion in a pro se mandamus proceeding arising from a criminal case. The novel feature of the opinion is its footnote (longer than the actual opinion), using the Court’s “discretion to take judicial notice of adjudicative facts that are matters of public record” to review the relevant online docket sheet to establish mootness. No. 05-20-00068-CV (March 11, 2020)

The trial court dismissed Heri Automotive’s counterclaims for forum non conveniens. Heri appealed. The Fifth Court dismissed because “no authority exists authorizing the appeal of the challenged interlocutory order,” and also noted that “appellant cites no authpority, and we have found none, that authorizes mandamus review of an interlocutory order granting a motion to dismiss for forum non conveniens.” Heri Automotive v. Adams, No. 05-19-01215-CV (Feb. 21, 2020) (mem. op.).

The trial court dismissed Heri Automotive’s counterclaims for forum non conveniens. Heri appealed. The Fifth Court dismissed because “no authority exists authorizing the appeal of the challenged interlocutory order,” and also noted that “appellant cites no authpority, and we have found none, that authorizes mandamus review of an interlocutory order granting a motion to dismiss for forum non conveniens.” Heri Automotive v. Adams, No. 05-19-01215-CV (Feb. 21, 2020) (mem. op.).

A 2018 article with an LPCH colleague considered when it is wise for an intermediate appellate court, subject to further review by the Texas Supreme Court, to take issues en banc. That article has been updated on this page on this website to reflect the supreme court’s recent Flakes opinion; only time will tell whether the recent rulings and dissents by the en banc Dallas court will draw supreme court interest.

After the 2018 election, an LPCH colleague and I wrote about the potential for renewed interest in “factual sufficiency” review–closely related to “legal sufficiency” review, but placed in the exclusive jurisdiction of the intermediate courts of appeal under the state constitution.

After the 2018 election, an LPCH colleague and I wrote about the potential for renewed interest in “factual sufficiency” review–closely related to “legal sufficiency” review, but placed in the exclusive jurisdiction of the intermediate courts of appeal under the state constitution.

An example appeared in In re C.V.L., where a panel majority reversed the termination of a parent-child relationship in a factual sufficiency review: “[E]vidence that Father used m ethamphetamines twice during the underlying proceedings and Bonds’ unsubstantiated belief that Father will use drugs again in the future because he used drugs twice in the past is not enough under a factual sufficiency review to permanently deprive Father and child of a relationship when weighed against all of the contrary, uncontroverted evidence presented at trial and the strong presumption that a child’s best interests are served by maintaining the parent–child relationship.”

ethamphetamines twice during the underlying proceedings and Bonds’ unsubstantiated belief that Father will use drugs again in the future because he used drugs twice in the past is not enough under a factual sufficiency review to permanently deprive Father and child of a relationship when weighed against all of the contrary, uncontroverted evidence presented at trial and the strong presumption that a child’s best interests are served by maintaining the parent–child relationship.”

A dissent saw the court of appeals’ role differently: “This case presents important questions regarding an appellate court’s ability to second guess a factfinder’s pivotal credibility determinations in a termination case given the supreme court’s admonition that despite the heightened standard of review in termination cases, courts of appeals must nevertheless still provide due deference to the factfinder’s credibility determinations.” No. 05-19-00506-CV (Dec. 13, 2019, pet. filed) (mem. op.)

Factual sufficiency review in this type of family-law case involves unique issues that may not arise in commercial disputes, but the case is still an important example of how this standard works in practice.

In a dispute about arbitrability, the plaintiff claimed never to have seen the arbitration agreement, and after receiving evidence about the defendant’s computer system, the trial judge agreed.

In a dispute about arbitrability, the plaintiff claimed never to have seen the arbitration agreement, and after receiving evidence about the defendant’s computer system, the trial judge agreed.

A panel majority affirmed the denial of the motion to compel arbitration: “Aerotek made the choice to forego in-person wet-ink signatures on paper contracts. This may be a good business decision that allows it to more efficiently process more business than otherwise possible. And in this case, Aerotek made the choice to bring only one person, an employee without apparent IT experience specific to the type of computer system whose technical reliability and security she sought to vouch for. Aerotek did this in the face of admitting it had contracted out creation and implementation of this system to another entity altogether and brought no witness from that entity. We conclude Aerotek did not present evidence establishing the opposite of a vital fact, here that appellees’ denials of ever seeing the a rbitration contracts were physically impossible given Aerotek’s computer system.”

rbitration contracts were physically impossible given Aerotek’s computer system.”

A dissent had a different view of the evidence and warned that as a policy matter: “This would allow any party to a contract signed electronically to deny the existence of the contract even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the contract was signed. Further, this holding amounts to a state rule discriminating on its face against arbitration, which is expressly prohibited.”

The en banc court denied review in a brief order (Justices Molberg (the trial judge) and Whitehill did not participate); a dissent by Justice Schenck reiterated the dissent’s warnings and “urge[d] prompt review by the Texas Supreme Court.” (joined by Justices Bridges (the panel dissenter), Evans, and Myers).

In the 2018 election for a Dallas County Justice of the Peace position, Democratic candidate Margaret O’Brien obtained a default judgment that her Republican opponent, Ashley Hutcheson, was ineligible for the position because of her residence. IAfter the  election, in December 2018, a Fifth Court panel reversed, finding that the order was void because an Election Code provision bars default judgments in election cases, and further finding that the matter was not moot and required a further trial-court order because the judgment included an award of attorneys’ fees.

election, in December 2018, a Fifth Court panel reversed, finding that the order was void because an Election Code provision bars default judgments in election cases, and further finding that the matter was not moot and required a further trial-court order because the judgment included an award of attorneys’ fees.

Litigation continued before the en banc court (the makeup of which significantly changed in the same 2018 election), which ultimately settled. In a short opinion by Chief Justice Burns on March 6, 2020, a majority of the Court dismissed the case as moot and withdrew the panel opinion.

Controversy ensued, as reflected by the four other opinions issued that day:

Controversy ensued, as reflected by the four other opinions issued that day:

- A dissent by Justice Schenck found that the matter was not moot (as it was capable

of repetition, etc.), agreed with the reasoning of the panel, and criticized the decision to withdraw the panel’s opinion (joined by Justices Bridges and Evans); - Another dissent, by Justice Whitehill, criticized the decision to withdraw the panel’s opinon for other reasons (also joined by Justice Bridges);

- A concurrence and dissent by Justice Bridges (the author of the panel opinion) agreed with the conclusion that the case is moot, disagreed with the withdrawal of the panel opinion, and reiterated the reasoning of that opinion (joined by Justices Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, and Evans — the full complement of Republican Justices on the present court);

- A concurrence by Justice Molberg clashed with the substantive reasoning of the dissents, but concluded that the order was void for another reason – ripeness – as the election had not yet occurred at the time of judgment. This opinion was joined by all other Democratic Justices on the court except Justice Pedersen, who did not participate in the case.

Liederman, a New York lawyer, sent seventy-seven emails to Texas, made five phone calls there, and signed and delivered three tolling agreements to Davis, a Texas-based attorney, “over a span of three years in working towards settling appellees’ claims.” The Fifth Court found no specific personal jurisdiction, observing: “Liederman could have ‘quite literally’ interacted with Davis, who could have been anywhere in the world, in the same manner. . . . It is apparent that Invasix’s contacts with Davis were based on her representation of the nonresident plaintiffs in the personal injury lawsuit and had nothing to do with the State of Texas.” Invasix, Inc. v. James, No. 05-19-00494-CV (Feb. 25, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added). The Court also found no general personal jurisdiction, applying recent Texas and United States Supreme Court opinions that have limited the scope of that doctrine.

Liederman, a New York lawyer, sent seventy-seven emails to Texas, made five phone calls there, and signed and delivered three tolling agreements to Davis, a Texas-based attorney, “over a span of three years in working towards settling appellees’ claims.” The Fifth Court found no specific personal jurisdiction, observing: “Liederman could have ‘quite literally’ interacted with Davis, who could have been anywhere in the world, in the same manner. . . . It is apparent that Invasix’s contacts with Davis were based on her representation of the nonresident plaintiffs in the personal injury lawsuit and had nothing to do with the State of Texas.” Invasix, Inc. v. James, No. 05-19-00494-CV (Feb. 25, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added). The Court also found no general personal jurisdiction, applying recent Texas and United States Supreme Court opinions that have limited the scope of that doctrine.

In Grisaffi v. Rocky Mountain High Brands, the Fifth Court reversed and remanded a default judgment after identifying an impermissible double recovery on the key issue: “Although Grisaffi committed numerous wrongful acts against Rocky Mountain, the default judgment awards Rocky Mountain $3.5 million as compensation for ‘funds obtained through fraud, breach of fiduciary duty and conversion with respect to Series A Preferred Stock . . . .’ The default judgment further awards Rocky Mountain declaratory relief to void the issuance of that Series A Preferred Stock. Thus, both the monetary and declaratory relief awarded to Rocky Mountain compensate it for the single injury of the wrongful issuance of Series A Preferred Stock caused by Grisaffi.” No. 05-18-01020-CV (Feb. 27, 2020) (mem. op.)

In Grisaffi v. Rocky Mountain High Brands, the Fifth Court reversed and remanded a default judgment after identifying an impermissible double recovery on the key issue: “Although Grisaffi committed numerous wrongful acts against Rocky Mountain, the default judgment awards Rocky Mountain $3.5 million as compensation for ‘funds obtained through fraud, breach of fiduciary duty and conversion with respect to Series A Preferred Stock . . . .’ The default judgment further awards Rocky Mountain declaratory relief to void the issuance of that Series A Preferred Stock. Thus, both the monetary and declaratory relief awarded to Rocky Mountain compensate it for the single injury of the wrongful issuance of Series A Preferred Stock caused by Grisaffi.” No. 05-18-01020-CV (Feb. 27, 2020) (mem. op.)

Section 171.025 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code says: “The court shall stay a proceeding that involves an issue subject to arbitration if an order for arbitration or an application for that order is made under this subchapter.” The dispute in In re: Baby Dolls Topless Saloon involved a mandamus petition from a defendant’s perceived inability to obtain an order implementing this stay, during its interlocutory appeal from denial of its motion to compel arbitration.

Section 171.025 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code says: “The court shall stay a proceeding that involves an issue subject to arbitration if an order for arbitration or an application for that order is made under this subchapter.” The dispute in In re: Baby Dolls Topless Saloon involved a mandamus petition from a defendant’s perceived inability to obtain an order implementing this stay, during its interlocutory appeal from denial of its motion to compel arbitration.

The panel majority denied the petition, finding that the issue of arbitrability “has been briefed in the interlocutory appeal and will be decided by the panel of justices assigned to decide that appeal, which is just as the legislature intended when it enacted section 51.016 and provided for an interlocutory appeal of an order denying a motion to compel arbitration. Because we follow the rule of law, we, as one panel of this Court, will not depart from this Court’s prior holding that mandamus will not issue when the legislature has expressly provided an adequate remedy by appeal.”

A dissent would have granted a stay as part of resolution of the mandamus petition, noting: “While our own statute and rules appear to compel the same result by dictating a stay of the overlapping proceedings of whatever court is first asked, we have not done so here. Accordingly, relator has properly brought the issue before us for mandamus relief that should be available under long recognized mandamus standards and without the need of further machination or a fifth request for stay.” No. 05-20-00015-CV (Feb. 24, 2020) (mem. op.)

In re Catapult Realty arose from a foreclosure that wound a complex path through the Dallas courthouse, and offers two practice reminders about such situations:

In re Catapult Realty arose from a foreclosure that wound a complex path through the Dallas courthouse, and offers two practice reminders about such situations:

- The judge of one district court signed a TRO on behalf of another district judge. The resulting order was void because “[t]he record does not reflect that another temporary injunction or other evidentiary hearing was held before the 298th district judge prior to her signing the 2nd TRO.”;

- A county court granted a plea in abatement based on her perceived inability to decide subject-matter jurisdiction. Mandamus relief was proper when this decision was incorrect legally, and where the resulting order “does not specify the circumstances that will allow for the case to be reinstated,” thus denying the plaintiff “the right to proceed to a resolution of the forcible-detainer action within a reasonable time.”

Nos. 05-19-01056-CV & -00109-CV (Feb. 20, 2020) (mem. op.)