My LPCH colleague John Adams and I recently published a similar version of this article in the Texas Lawbook:

Newly elected judges on courts of appeals may soon find themselves at odds with the steadfastly conservative Texas Supreme Court. As the intermediate courts of appeals grapple with their role in shaping Texas jurisprudence, a firmly rooted – albeit faded – distinction between factual and legal sufficiency may return to a prominent place in appellate review. Specifically, courts of appeals may be able to limit state Supreme Court review by deciding cases based on factual sufficiency of the evidence.

This distinction between legal and factual sufficiency review is a unique feature of Texas practice. It stems from the Texas Constitution, which says that “[T]he decision of said courts [of appeals] shall be conclusive on all questions of fact brought before them on appeal or error.”

Thus, whether or not evidence is factually sufficient is a question for courts of appeals that the Texas Supreme Court cannot review.

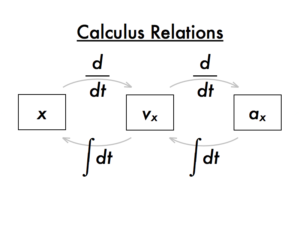

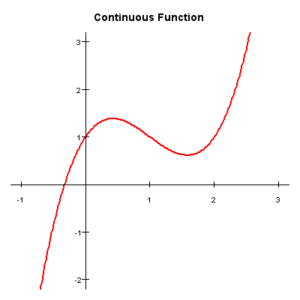

Factual sufficiency is commonly understood to be a higher threshold than legal sufficiency, although in practice it can be difficult to distinguish the two standards. As the legal sufficiency standard has evolved toward an “inclusive” review of evidence (in other words, considering all evidence) – particularly after cases such as City of Keller v. Wilson – that standard has become less distinguishable from factual sufficiency.

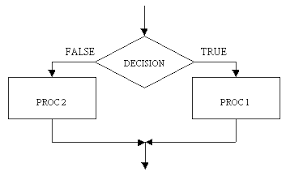

Nonetheless, a distinction remains. Generally, under a factual sufficiency standard of review, a court of appeals must consider all evidence but may disregard evidence in support of a verdict if that evidence is against the clear weight and preponderance of other evidence. On the other hand, to determine legal sufficiency, a court must consider all evidence in a light favorable to the verdict – disregarding only evidence a reasonable jury couldn’t consider.

The effect of this distinction is that if a court of appeals determines that evidence is factually insufficient (although legally sufficient), the Texas Supreme Court is stuck with that decision, assuming the court of appeals applied the correct standard.

So the Texas Supreme Court cannot review whether the evidence is factually sufficient, but it can review whether the court of appeals conducted the appropriate analysis. This means the court of appeals must “detail the relevant evidence and clearly state why the evidence is factually insufficient.”

For decades, the distinction between factual and legal sufficiency has had minimal effect. The courts of appeals and the state Supreme Court have generally been in harmony about how to apply the standards of review. But for three decades, justices on the major courts of appeals and Texas Supreme Court were mostly elected from the same party with relatively low turnover.

But now, Texas has a fresh class of justices in many courts of appeals. For example, for the first time in 30 years, the Fifth Court of Appeals will be composed of mostly justices elected from the Democratic Party. Of course, many of these newly elected justices may have different perspectives from legacy state Supreme Court justices.

One way that new friction between the courts of appeals and the Texas Supreme Court may manifest is through a revitalized distinction between factual and legal sufficiency. In particular, courts of appeals may emphasize factual sufficiency to limit the Supreme Court’s review.

In In re: Rohrich, the relator sought “a writ of mandamus directing the trial court to vacate a May 2, 2019 show cause order and a March 4, 2019 order compelling production of data referenced in an April 2018 article written by relator.”

In In re: Rohrich, the relator sought “a writ of mandamus directing the trial court to vacate a May 2, 2019 show cause order and a March 4, 2019 order compelling production of data referenced in an April 2018 article written by relator.”

er 23 Order indicates the trial [judge] intended for its September 22 Order to constitute a final and appealable judgment that disposed of all claims.” Unfortunately for the appeal, however, the Fifth Court noted (1) “factual recitations or reasons preceding the decretal portion of a judgment form no part of the judgment itself,” and (2) “the October 23 Order cannot constitute a final judgment because it lacks the decretal language typically seen in a judgment” [such as “ordered, adjudged, and decreed,” etc.]. Because of these shortcomings with the October 23 Order, and the September 22 Order’s failure to address all causes of action or include Lehmann finality language, there was no final judgment and thus no appellate jurisdiction. No. 05-17-01228-CV (Dec. 18, 2018) (mem. op.)

er 23 Order indicates the trial [judge] intended for its September 22 Order to constitute a final and appealable judgment that disposed of all claims.” Unfortunately for the appeal, however, the Fifth Court noted (1) “factual recitations or reasons preceding the decretal portion of a judgment form no part of the judgment itself,” and (2) “the October 23 Order cannot constitute a final judgment because it lacks the decretal language typically seen in a judgment” [such as “ordered, adjudged, and decreed,” etc.]. Because of these shortcomings with the October 23 Order, and the September 22 Order’s failure to address all causes of action or include Lehmann finality language, there was no final judgment and thus no appellate jurisdiction. No. 05-17-01228-CV (Dec. 18, 2018) (mem. op.)