Following up on the Orca opinion’s memorable warning about “red flags” and justifiable reliance, in American Midstream v. Rainbow Energy Marketing Corp. the Texas Supreme Court held that “[t]he e courts below impermissibly blue-penciled extra words into … the contract that gave rise to this dispute …” (specifically, reading the contract as if the words “scheduled” and “physical” appeared in a key contract term about deliveries). No. 23-0384 (Tex. May 23, 2024).

Following up on the Orca opinion’s memorable warning about “red flags” and justifiable reliance, in American Midstream v. Rainbow Energy Marketing Corp. the Texas Supreme Court held that “[t]he e courts below impermissibly blue-penciled extra words into … the contract that gave rise to this dispute …” (specifically, reading the contract as if the words “scheduled” and “physical” appeared in a key contract term about deliveries). No. 23-0384 (Tex. May 23, 2024).

Category Archives: Contract

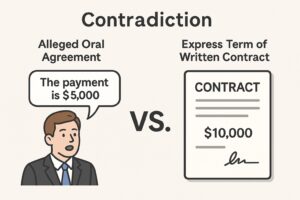

In Roxo Energy, LLC v. Baxsto, LLC, LLC, the Texas Supreme Court addressed (again) the element of justifiable reliance, in the context of alleged oral promises that contradicted written agreements.

In Roxo Energy, LLC v. Baxsto, LLC, LLC, the Texas Supreme Court addressed (again) the element of justifiable reliance, in the context of alleged oral promises that contradicted written agreements.

Specifically, the Court held that claims based on oral representations about the lessee’s intent to develop the mineral lease, rather than “flip” it, failed ecause the written lease expressly let the lessee transfer its interest with no obligation to drill or develop the land. The Court emphasized that “an unqualified contractual right to transfer a lease contradicts a prior oral promise not to do so,” making reliance on such oral promises unjustifiable.

The Court also rejected claims based on alleged misrepresentations about bonus payments. The only written commitment about bonus payments was a “most favored nations” clause, which was not breached. The Court explained that the absence of any language in the written agreements confirming the alleged oral representations about bonus amounts was itself a “red flag negating justifiable reliance””–“[T]he prudent response is to demand that the parties’ discussions be reflected in the writing—not to sign an agreement that makes no mention of the promises and then try to hold your counterparty to them anyway.”

No. 23-0564, Tex. May 9, 2025.

In Luxottica of Am., Inc. v. Gray, the Court of Appeals addressed the element of justifiable reliance in the context of fraud and related claims arising from the sale of franchise stores.

The Court held that the existence of clear contractual disclaimers and “as-is” provisions in the relevant agreements conclusively negated the element of justifiable reliance, which is required to prove claims for common-law fraud, civil conspiracy, and statutory

fraud. Specifically, the court pointed to language in the franchise and purchase agreements stating that the buyer “did not rely on any incidental statements about success made by [Luxottica], its affiliates or employees” and that the business was being conveyed “AS IS WHERE IS, WITHOUT WARRANTY EXPRESSED OR IMPLIED.” No. 05-23-00020-CV (May 5, 2025) (mem. op.). (LPHS represented the successful appellant in this case.)

Davis v. Homeowners of Am. addressed the enforceability of a contractual limitations period in an insurance policy.

Davis v. Homeowners of Am. addressed the enforceability of a contractual limitations period in an insurance policy.

The Fifth Court held that the policy’s provision requiring suit to be filed within two years and one day from the date the claim is accepted or rejected, or three years and one day from the date of the loss, did not violate Texas Civil Practice and Remedies Code § 16.070(a).

The Court distinguished this case from Spicewood Summit Office Condos Ass’n v. Am. First Lloyds Co. noting that the policy in Davis did not impermissibly shorten the limitations period to less than two years, as the trigger date was based on the claim’s acceptance or rejection rather than the date of loss. No. 05-24-00035-CV, Apr. 7, 2025 (mem. op.).

McDonald v. Four Rivers Devel., LLC, discussed yesterday on a procedural point, also addressed the distinction between a condition precedent and a covenant within a contract. The Fifth Court held that a 25% profit margin requirement for commission payments was not a condition precedent but rather a covenant or term of the contract.

McDonald v. Four Rivers Devel., LLC, discussed yesterday on a procedural point, also addressed the distinction between a condition precedent and a covenant within a contract. The Fifth Court held that a 25% profit margin requirement for commission payments was not a condition precedent but rather a covenant or term of the contract.

It explained, “We do not view the 25% profit margin requirement as a condition precedent that would require a specific denial. The provision – commissions calculated at 6% for any job sold by McDonald in which the overall profit on the job was 25% or more – was the measure of calculating commissions, i.e., a covenant or term of the contract.”

A condition precedent is an event that must occur before a right can accrue to enforce an obligation, while a covenant is an agreement to act or refrain from acting in a certain way. The court emphasized that this did not indicate an “if this, then that” scenario, as typical of a condition precedent. Instead, the 25% profit margin was a term used to calculate commissions, making it a covenant. No. 05-24-00431-CV (March 28, 2025) (mem. op.).

Texas law favors arbitration agreements – but even the most favorable view of the topic requires an agreement. In Exencial Wealth Advisors, LLC v. Sipes, the relevant contract required a signature to become effective, and the record did not contain a signed copy of that instrument. Therefore, the contract failed for lack mutual assent, and arbitration of the parties’ dispute was not required. No. 05-24-00964-CV (Jan. 31, 2025) (mem. op.).

Texas law favors arbitration agreements – but even the most favorable view of the topic requires an agreement. In Exencial Wealth Advisors, LLC v. Sipes, the relevant contract required a signature to become effective, and the record did not contain a signed copy of that instrument. Therefore, the contract failed for lack mutual assent, and arbitration of the parties’ dispute was not required. No. 05-24-00964-CV (Jan. 31, 2025) (mem. op.).

The parties’ lease in Lamar Advantage Outdoor Co. v. LaCore Enterprises, LLC contained this provision, which the Fifth Court held to create a right of first refusal (as opposed to a purchase option):

The parties’ lease in Lamar Advantage Outdoor Co. v. LaCore Enterprises, LLC contained this provision, which the Fifth Court held to create a right of first refusal (as opposed to a purchase option):

If LESSOR desires to sell or otherwise transfer any Interest in the property upon which the sign is situated, LESSOR grants LESSEE an option to purchase a perpetual easement (servitude) encompassing the sign and the access, utility service and visibility rights set forth herein. LESSEE must elect to exercise this option within thirty (30) days after written notification of LESSOR’s desire to sell. LESSEE’S failure to exercise this option within said period shall be a waiver of this option. …

Following an earlier Fifth Court case about a similar clause, the Court held that because this provisision was not “limit[ed to] the right of first refusal to the first sale or transfer of the Property or contemplating waiver of the right if not utilized in conjunction with prior transactions.” No. 05-23-00210-CV (Dec. 31, 2024) (mem. op.).

A party sought to avoid the effect of a “prevailing party” attorneys’ fee provision in MRT of Kemp TX-SNF, LLC v. Lloyd Douglase Enterprises LC. The Fifth Court disagreed:

“MRT is not a party to PSA 1. But MRT embraced PSA 1 by seeking to enforce its terms. By doing so, MRT subjected itself to the entirety of the terms of PSA 1, including the attorney’s fee provision in Article 28.”

No. 05-23-00574-CV (Sept. 5, 2024).

Madonna reached #2 on the charts in 1985 with “Material Girl.” In Bain & Schindele Tax Consulting, LLC v. EW Tax & Valuation Group, LLP, the Fifth Court found that when the trial court found a party’s breach of a non-solicitation obligation to be material and unjustified, it erred by not fully excusing the other contracting party from further performance of the contract obligations (in that case, certain note payments). No. 05-23-00560-CV (Aug. 7, 2024).

Madonna reached #2 on the charts in 1985 with “Material Girl.” In Bain & Schindele Tax Consulting, LLC v. EW Tax & Valuation Group, LLP, the Fifth Court found that when the trial court found a party’s breach of a non-solicitation obligation to be material and unjustified, it erred by not fully excusing the other contracting party from further performance of the contract obligations (in that case, certain note payments). No. 05-23-00560-CV (Aug. 7, 2024).

At issue in Robinson v. Boral Windows LLC was the scope of a release, which addressed “any and all actions … from the beginning of time to the present, including any and acts or omissions occurring to date … specifically includ[ing] without limitation all matters arising out of … the Employment Agreement ….” After a comprehensive review of case law involving similar terms, the Fifth Court held:

At issue in Robinson v. Boral Windows LLC was the scope of a release, which addressed “any and all actions … from the beginning of time to the present, including any and acts or omissions occurring to date … specifically includ[ing] without limitation all matters arising out of … the Employment Agreement ….” After a comprehensive review of case law involving similar terms, the Fifth Court held:

- The release was not limited to the identified Employment Agreement, given the other, broader language in the release;

- For similar reaons, the release included claims based on two other instruments, even thought they were not specificaly identified in the release;

- The release extended to a successor-in-interest to one of the parties, by operation of law and because it had a standard “all predecessors, successors [and] assigns” clause.

No. 05-22-01184-CV (June 10, 2024) (mem. op.).

A popular meme shows Oprah Winfrey giving cars away to everyone in sight. In Pack Properties XIV, LLC v. Remington Prosper, LLC, the Fifth Court found fact issues all ’round, and held that all parties summary-judgment motions should be denied in a dispute about a contract related to the establishment of a car dealership. Two key points were:

A popular meme shows Oprah Winfrey giving cars away to everyone in sight. In Pack Properties XIV, LLC v. Remington Prosper, LLC, the Fifth Court found fact issues all ’round, and held that all parties summary-judgment motions should be denied in a dispute about a contract related to the establishment of a car dealership. Two key points were:

- Under Fifth Court precedent, the term “affiliate” in a contract “is generally defined as a ‘corporation that is related to another corporation by shareholdings or other means of control’ and as a ‘company effectively controlled by another or associated with others under common ownership or control.'” Applying that precedent, the record presented a fact issue about “whether sufficient control” existed among the relevant parties.

- “Materiality” arises in two distinct settings. In one, “a court must determine if the parties’ agreement is sufficiently certain to be an enforceable contract. The question generally arises when the agreement lacks a particular term or contains a term that is unclear. The ultimate issue in this kind of case is the existence of a valid contract, which is a legal question.” In the other, “the question is whether a breach by one party was sufficiently important to excuse the other party’s continuing performance, i.e., the affirmative defense of prior material breach. These cases do not address a missing term and its effect on the validity of a contract; instead, these cases look to the significance of a particular term within the total agreement. Courts performing this analysis address the materiality issue as a fact question.”

The Fifth Court held in Rudnicki v. Thompson Petroleum Corp. that a former oil-company executive was not entitled to indemnity for certain litigation expenses, agreeing with the company’s position that: ““[Partnership’s] Agreement could have provided for indemnification of expenses incurred ‘based on,’ ‘arisin(g from,’ or similarly ‘related to’ a covered person’s performance of the obligations of the GP with respect to [the Partnership]. But that simply is not what it says.” The company was authorized to indemnify the executive, but was not required to do so. No. 05-23-00125-CV (March 20, 2024) (mem. op.).

In the atypical setting of an appeal from an arbitration award (under the TAA), the Fifth Court concluded that the price set by an option agreement was sufficiently definite:

In the atypical setting of an appeal from an arbitration award (under the TAA), the Fifth Court concluded that the price set by an option agreement was sufficiently definite:

[T]he Option Provision included a formula to determine the purchase price, limiting the purchase price to the greater of the mutually agreed upon appraiser’s calculations, including assumption guidelines for same, or a definite sum of taxes owing, present value of anticipated tax credits not yet received by limited partner, and $100.00. In reaching this conclusion, we reject MHT’s argument that this case is similar to that of Playoff Corp. v. Blackwell, in which the parties entered into an employment contract that promised the employee 25% of a portion of the company’s fair market value upon his termination but did not agree, however, on how the company’s fair market value would be determined, instead agreeing that it would be determined based on a specific formula that the parties would have to agree to in the future after “later negotiations.”

The Court also said: “[W]e agree with other courts that have held that when parties to an agreement specify that a third person is to fix the price, the contract is not unenforceable for lack of definiteness.” Multi-Housing Tax Credit Partners XXXI v. White Settlement Senior Living, LLC, No. 05-22-00721-CV (Jan. 26, 2024) (mem. op.).

Wakefield, a party to a civil lawsuit, disputed a judgment against him in favor of Rubio, forensic expert retained by his counsel in that lawsuit. Wakefield argued that no evidence established a contract between him and the expert. But the identify of his counsel was undisputed (thus providing some evidence of agency), and additional evidence showed that he ratified his counsel’s dealings with the expert, establishing that he chose to proceed:

Wakefield, a party to a civil lawsuit, disputed a judgment against him in favor of Rubio, forensic expert retained by his counsel in that lawsuit. Wakefield argued that no evidence established a contract between him and the expert. But the identify of his counsel was undisputed (thus providing some evidence of agency), and additional evidence showed that he ratified his counsel’s dealings with the expert, establishing that he chose to proceed:

… after (1) learning Tadlock engaged Rubio to perform expert services with respect to his case, (2) understanding how important the admissibility of evidence from the watch was, (3) personally delivering the watch to Rubio, (4) instructing Rubio to do as his attorney instructed, and (5) learning upon his arrival at the courthouse for his hearing that Rubio’s bill was approaching $10,000.

Wakefield v. Rubio Digital Forensics LLC, Nov. 21, 2023 (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court reviewed the interplay between the COVID pandemic and a “force majeure” clause in a commercial lease in BB Fit v. EREP Preston Trail II:

The Fifth Court reviewed the interplay between the COVID pandemic and a “force majeure” clause in a commercial lease in BB Fit v. EREP Preston Trail II:

[T]he parties expressly agreed that delays due to enumerated causes beyond the parties’ reasonable control would be excluded from computations of time. They did not agree to discharge BB FIT’s obligation to pay rent; to the contrary, Lease § 4(d) provides that “[t]he obligation of Tenant to pay Rent and the obligations of Tenant to perform other covenants and duties hereunder constitute independent and unconditional obligations of Tenant to be performed at all times as provided hereunder.” We conclude these express terms govern, specifically providing for an extension of time to pay rent rather than a discharge of the obligation.

No. 05-22-00682-CV (Nov. 9, 2023). (Our firm represented the successful party.)

In U.S. Polyco, Inc. v. Texas Central Business Lines Corp., the Texas Supreme Court reversed a contract case based on the definition of ambiguity. The court also rejected an argument for affirmance based on “context,” stating:

The task of harmonizing contracts entails reconciling otherwise conflicting contractual provisions. That task does not authorize courts to ensure that every provision comports with some grander theme or purpose, particularly when the parties have not said in the contract which purpose matters most or that everything else in thecontract should be read subject to that purpose. To hold otherwise would implicitly assume that contracting parties pursue a purpose (at whatever generality) at all costs.

No. 22-0901(footnote omitted).

Note that this concept is distinct from “commercial context”–the circumstances surrounding the execution of a contract, within the reasonable awareness of parties. See, e.g., Kachina Pipeline Co. v. Lillis, 471 S.W.3d 445 (Tex. 2015) (“We may consider the facts and circumstances surrounding a contract, including ‘the commercial or other setting in which the contract was negotiated and other objectively determinable factors that give context to the parties’ transaction.'” (citation omitted)).

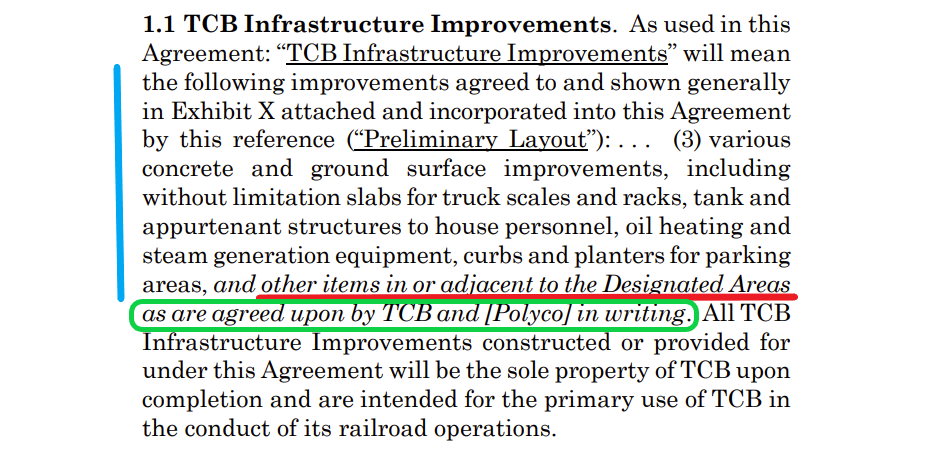

In U.S. Polyco, Inc. v. Texas Central Business Lines Corp., the Texas Supreme Court reviewed a contract dispute, and gave a reminder about a basic principle of contract interpretation.

The dispute involved the below language about “other items … as are agreed upon by TCB and [Polyco] in writing” (green, below).

One side contended that it applied only to the “other items” Designated Areas” referred to earlier in the clause (red, below). The other argued that it reached all items listed in the full paragraph (blue, below):

The trial court, court of appeals, and supreme court all agreed that the bettter reading of the “in writing” clause was that it only related to the “other items” (noting, among other matters, the importance of the “Oxford comma”). But the court of appeals found ambiguity, based on its characterization of the parties’ dueling interpretations as reasonable, and that is the point on which the supreme court reversed:

This analysis is erroneous for two basic reasons. First, like all other considerations beyond the contract’s language and structure, parties’ “disagreement” about their intent is irrelevant to whether that text is ambiguous. Parties who find themselves in a business dispute can always claim an extratextual “intent” that would serve a current litigation position. Second, the “multiple, reasonable interpretations” that the court of appeals invoked are illusory. If there were multiple interpretations and a court could not choose among them, then the text would be genuinely ambiguous and there would be no choice but to leave the question to a jury. But the multiple interpretations that the court was referencing here were merely the competing theories that the parties advanced about how to read the text—a dispute that both the trial and appellate courts had ably addressed as a matter of law.

No. 22-0901 (Nov. 3, 2023) (emphasis removed).

While option agreements are an important part of commercial law, their specific legal requirements are not as frequently litigated as other contract-law concepts. Vertical Holdings, LLC v. LocatorX, Inc. holds that a failure to pay a specified $1,000 price precluded exercise of an option, because:

While option agreements are an important part of commercial law, their specific legal requirements are not as frequently litigated as other contract-law concepts. Vertical Holdings, LLC v. LocatorX, Inc. holds that a failure to pay a specified $1,000 price precluded exercise of an option, because:

Under Texas law, to exercise an option, “strict compliance with the provisions of an option contract is required … [A]cceptance of an option must be unqualified, unambiguous, and strictly in accordance with the terms of the contract.” And “any failure to exercise an option according to its terms, including untimely or defective acceptance, is simply ineffectual, and legally amounts to nothing more than a rejection.

No. 05-22-00720-CV (Sept. 13, 2023) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

AMPM Enterprises v. Borders, a dispute about alleged failures to pay for gasoline deliveries to service stations, presented a good example of a basic issue, and an interesting example of a less common one.

AMPM Enterprises v. Borders, a dispute about alleged failures to pay for gasoline deliveries to service stations, presented a good example of a basic issue, and an interesting example of a less common one.

- Proveup. “Here, Borders’ December 23, 2020 affidavit established that he was the vice president of Borders and was responsible for overseeing the maintenance of Borders’ books and records of sales and accounts and was the custodian of such records. The affidavit stated that the table showing a balance of $42,151.82 owed by AMPM and PTE was ‘a true and correct copy of Borders’ records reflecting charges incurred by AMPM and PTE for gasoline delivered to AMPM and PTE’s stores or related fees or services incurred pursuant to the agreement of the parties,’ and the table was ‘created in the ordinary course of business and reflects a systematic record of the amounts owed by AMPM and PTE to Borders.’”

- Performance. “It is not disputed that AMPM and Asghar entered into contracts with Borders in October 2010 to provide fuel at four locations, and Borders continued to provide fuel, and AMPM continued to pay for it, until some time in 2017. Borders and PTE commenced an oral relationship involving requests and delivery of fuel in 2017. During that transactional history, AMPM, Asghar, and PTE did not complain about fees included in the price of fuel or challenge the validity of their contracts with Borders. Under the facts and circumstances of this case, we conclude neither the absence of a price specified in the underlying contracts nor the absence of provisions for the payment of “monthly fees, network fees, and mystery shoppers fees” raised a fact issue as to the amounts owed to Borders under the contracts.”

Aflalo v. Harris arose from a contract to sell a house. The question was (generally) how to calculate the value of the house at the contractually specified sales time, and (specifically) when a later resale of a home can be probative of that value. The Fifth Court reviewed the specific facts of this resale to determine that it was probative, discussing and distinguishing Barry v. Jackson, 309 S.W.3d 135 (Tex. App.–Austin 2010, no pet.) (LPHS represented the successful appellant in this case.)

The classic question of “who” was central to Western Healthcare LLC v. Herda, which involved the role of a “contractual delay” provision as a defense to a suit alleging a failure to pay certain workers: “[Plaintiffs] contended that because the work stoppage at issue affected Ellwood, rather than WHC, it should not defeat their claims. But the contractual provision does not specify that a particular employer must undergo a work stoppage to trigger its application; Ellwood’s closure certainly stopped the Providers’ ability to work at its hospital, which was the work bargained for in their contracts.” No. 05-21-00603-CV (Feb. 10. 2023) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

The classic question of “who” was central to Western Healthcare LLC v. Herda, which involved the role of a “contractual delay” provision as a defense to a suit alleging a failure to pay certain workers: “[Plaintiffs] contended that because the work stoppage at issue affected Ellwood, rather than WHC, it should not defeat their claims. But the contractual provision does not specify that a particular employer must undergo a work stoppage to trigger its application; Ellwood’s closure certainly stopped the Providers’ ability to work at its hospital, which was the work bargained for in their contracts.” No. 05-21-00603-CV (Feb. 10. 2023) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

In a Tarot deck, the “Magician” (right) has the power to transform. In the Fifth Court, however, the phrase “reasonable and necessary” is not a “magic word.”

In a Tarot deck, the “Magician” (right) has the power to transform. In the Fifth Court, however, the phrase “reasonable and necessary” is not a “magic word.”

In a construction-contract dispute, even though “no witness explicitly testified that the expenses incurred were reasonable and necessary,” the Court reversed a JNOV and reinstated judgment on the jury’s verdict when the evidence allowed the jury to infer that the costs incurred were reasonable and necessary. That evidence included:

- detailed invoices;

- presented by a witness with extensive relevant experience;

- with a contract-based incentive to not incur excessive expense;

- general consistency with an estimate presented by the other side.

Bosque v. Barbosa, No.05-22-00230-CV (Jan. 30, 2023) (mem. op.). (Congrats to my LPHS colleague Greg Brassfield who tried the underlying case and successfully argued this appeal!)

These events produced a triable fact issue about whether the parties renewed a lease:

- On March 1, Property Manager emails Tenant about lease renewal, noting that “rent will be increasing to $2,275/month” from the current $2,200 monthly amount.

- That same day, Tenant responds that “yes, I would like to renew the lease. I will follow up this weekend with more information.”

- On March 12, Tenant sent a lengthy email about problems with her air conditioning, claimed roughly $4000 dollars in damages as a result, and ended: “I still intend to renew the lease and this settlement offer does not constitute a counter offer or rejection to your lease renewal offer on March 1 ….”

- On March 13, Property Owners’ counsel sent a notice of termination.

The Fifth Court noted: “Under the common law, an acceptance may not change or qualify the material terms of the offer, and an attempt to do so results in a counteroffer rather than an acceptance.” Bismar v. Mitchell, No. 05-21-00104-CV (Jan. 27, 2023) (mem. op.).

Maersk v. Mgbeowula presented what Maersk (the shipping company) apparently considered to be a collection matter arising from a freight delivery to Nigeria, and what the defendant contended was a problem created by an agent acting without authority. When Maersk’s Texas-law contract claims encountered rough seas at trial, it sought leave to amend with a claim based on maritime law. The trial court denied that request and the court of appeals affirmed, declining to raise that ship by concluding (among other matters) that there had been no trial by consent of such a claim:

Maersk v. Mgbeowula presented what Maersk (the shipping company) apparently considered to be a collection matter arising from a freight delivery to Nigeria, and what the defendant contended was a problem created by an agent acting without authority. When Maersk’s Texas-law contract claims encountered rough seas at trial, it sought leave to amend with a claim based on maritime law. The trial court denied that request and the court of appeals affirmed, declining to raise that ship by concluding (among other matters) that there had been no trial by consent of such a claim:

“[T]he evidence admitted at trial was submitted by Maersk in support of its claims for breach of contract and sworn account under Texas law. Because the evidence was relevant to the pleaded claims, we cannot conclude that a claim under maritime law was tried by consent. … This is particularly so in light of Mgbowula’s objection at the start of trial to the use of any exhibit to invoke maritime law. While the evidence offered by Maersk might be relevant to a cause of action under maritime law, this does not change the fact that the requested amendment asserted a new substantive matter that would have reshaped Maersk’s case.”

No. 05-21-00820-CV (Jan. 20, 2023).

The Fifth Court reviewed a commercial, “triple net” lease in Gaedeke Holdings II v. Chait & Henderson, concluding: “Under the Lease, the fixed amount Uptown paid in the first calendar year of the Lease term does not have any effect on the computation of Uptown’s “Pro Rata Share of Basic Costs” after the first calendar year, and in years two and beyond, Uptown’s “Pro Rata Share of Basic Costs” is based on Gaedeke’s Basic Costs in 2016, subject only to the 6 percent year-over year limitation on increases to Gaedeke’s controllable Basic Costs in 2016.” No. 05-20-01048-CV (Dec. 29, 2022) (mem. op.). An interesting amicus brief discusses different kinds of commercial leases.

The Fifth Court reviewed a commercial, “triple net” lease in Gaedeke Holdings II v. Chait & Henderson, concluding: “Under the Lease, the fixed amount Uptown paid in the first calendar year of the Lease term does not have any effect on the computation of Uptown’s “Pro Rata Share of Basic Costs” after the first calendar year, and in years two and beyond, Uptown’s “Pro Rata Share of Basic Costs” is based on Gaedeke’s Basic Costs in 2016, subject only to the 6 percent year-over year limitation on increases to Gaedeke’s controllable Basic Costs in 2016.” No. 05-20-01048-CV (Dec. 29, 2022) (mem. op.). An interesting amicus brief discusses different kinds of commercial leases.

Kam v. Adams, an attorney-client dispute about a retainer agreement, produced reference points on basic aspects of summary-judgment practice:

Kam v. Adams, an attorney-client dispute about a retainer agreement, produced reference points on basic aspects of summary-judgment practice:

- “Because Adams’s evidence serves only to raise a fact issue, Kam was not required to offer a response to the motion for summary judgment or contradictory proof. ‘In our summary judgment practice, the opponent’s silence never improves the quality of a movant’s evidence.’” (citation omitted).

- “Although Adams disputes that this was their understanding, he is an interested witness. For the testimony of an interested witness to establish a fact as a matter of law, there must be no circumstances in evidence tending to discredit his testimony. Such circumstances are presented here by Kam’s complete reliance on Thomas in the creation and negotiation of the retainer agreement, as well as the continued negotiations and apparent changes made to the agreement, including to the non-refundable fee specifically, after Kam signed it.”

- In the specific context of intent to form a contract: “Intent is a fact question uniquely within the realm of the trier of fact because it depends upon the credibility of the witnesses and the weight to be given to their testimony.” (citation omitted).

No. 05-21-00871-CV (Nov. 3, 2022) (mem. op.).

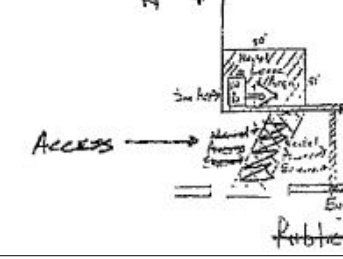

Among many other issues, a question in LSC Towers, LLC v. LG Preston Campbell, LLC was whether a lease unambiguously foreclosed an access-easement claim:

In a (literally) picture-perfect description of ambiguity, the Fifth Court found this diagram ambiguous when “what might be a drawn pathway leading to the cell-tower lot from the south is scratched out, the word ‘Access’ with an arrow pointing to that same area is not scratched out.” No. 05-20-00433-CV (Aug. 30, 2022) (mem. op.).

In a (literally) picture-perfect description of ambiguity, the Fifth Court found this diagram ambiguous when “what might be a drawn pathway leading to the cell-tower lot from the south is scratched out, the word ‘Access’ with an arrow pointing to that same area is not scratched out.” No. 05-20-00433-CV (Aug. 30, 2022) (mem. op.).

The defense of waiver was not conclusively established in a contract dispute when:

“The only evidence we see that could potentially support waiver is the $85,000 check that Ganguly accepted from Kaur Ltd. But we conclude that this evidence does not suffice. Although the check bears the notation “For KERSEVA DEBT,” that notation does not indicate that the funds are being offered as payment in full; thus Ganguly’s acceptance of the check, without more, is no evidence of intent to relinquish Ganguly Holdings’ claim against Ker-Seva or of intentional conduct inconsistent with asserting that claim.”

Ganguly Holdings, LLC v. Ker-Seva, Ltd., No. 5-21-00124-CV (July 29, 2022) (mem. op.)

The Fifth Court provided a valuable reminder about the enforcement of post-litigation agreements in Patel v. Gonzalez Hotels:

“Written settlement agreements may be enforced as contracts even if one party withdraws consent before judgment is entered on the agreement. When consent is withdrawn, however, the agreed judgment that was part of the settlement may not be entered. The party seeking enforcement of the settlement agreement must pursue a separate claim for breach of contract, which is subject to the normal rules of pleading and proof.” (citation omitted).

However, this principle does not apply to all agreements covered by Tex. R. Civ. P. 11, such as stipulations about evidentiary matters, as discussed in this article I co-authored a couple of years ago on the subject. (A big 600Commerce thanks to the able Ben Taylor for drawing this case to my attention!)

In bringing to an end a long-running international oil-and-gas dispute, the Texas Supreme Court examined a seeming tension between two earlier opinions about the specificity required for an effective release: “‘[W]hile the misrepresentation in Schlumberger “pertained to the very matter negotiated, settled, and released,”‘ the misrepresentation in Forest Oil ‘did not concern known disputed matters (which were settled and released) but potential future disputes (which were set aside and reserved).'” The Court concluded:

In bringing to an end a long-running international oil-and-gas dispute, the Texas Supreme Court examined a seeming tension between two earlier opinions about the specificity required for an effective release: “‘[W]hile the misrepresentation in Schlumberger “pertained to the very matter negotiated, settled, and released,”‘ the misrepresentation in Forest Oil ‘did not concern known disputed matters (which were settled and released) but potential future disputes (which were set aside and reserved).'” The Court concluded:

“Here, the evidence does not suggest that the parties actually considered or discussed allegations that Astra representatives bribed Petrobras officials to approve the 2006 stock-purchase agreement or offered to bribe them to approve the 2012 settlement agreement. But the evidence—including the terms of the settlement agreement itself does establish that the parties entered into the settlement agreement only after an extended series of complex and hotly contested negotiations that included discussions about the need to resolve all prior, pending, and possible claims between the parties, including those that were ‘unknown’ at the time.”

Transcor Astra Group S.A. v. Petrobras America Inc., No. 20-0932 (Tex. April 29, 2022).

After a split decision from the Fifth Court declined to send a personal-injury case to arbitration, the Texas Supreme Court ruled otherwise in Baby Dolls v. Sotero: “The Family’s argument, and the court of appeals’ holding, that Hernandez and the Club never had a meeting of the minds on the contract blinks the reality that they operated under it for almost two years, week after week, before Hernandez’s tragic death. We hold that the parties formed the agreement reflected in the contract they signed.” No. 20-0782 (Tex. March 18, 2022).

After a split decision from the Fifth Court declined to send a personal-injury case to arbitration, the Texas Supreme Court ruled otherwise in Baby Dolls v. Sotero: “The Family’s argument, and the court of appeals’ holding, that Hernandez and the Club never had a meeting of the minds on the contract blinks the reality that they operated under it for almost two years, week after week, before Hernandez’s tragic death. We hold that the parties formed the agreement reflected in the contract they signed.” No. 20-0782 (Tex. March 18, 2022).

In Hadley v. Baxendale, 8 Exch. 341, 156 Eng. Rep. 145 (1854), the Court of Exchequer held that a miller’s lost profits, arising from the late delivery of a replacement shaft for a steam engine in the mill, were not recoverable as consequential damages in a suit for breach of contract: “But it is obvious that, in the great multitude of cases of millers sending off broken shafts to third persons by a carrier under ordinary circumstances, such consequences would not, in all probability, have occurred, and these special circumstances were here never communicated by the plaintiffs to the defendants. It follows, therefore, that the loss of profits here cannot reasonably be considered such a consequence of the breach of contract as could have been fairly and reasonably contemplated by both the parties when they made this contract.”

In Hadley v. Baxendale, 8 Exch. 341, 156 Eng. Rep. 145 (1854), the Court of Exchequer held that a miller’s lost profits, arising from the late delivery of a replacement shaft for a steam engine in the mill, were not recoverable as consequential damages in a suit for breach of contract: “But it is obvious that, in the great multitude of cases of millers sending off broken shafts to third persons by a carrier under ordinary circumstances, such consequences would not, in all probability, have occurred, and these special circumstances were here never communicated by the plaintiffs to the defendants. It follows, therefore, that the loss of profits here cannot reasonably be considered such a consequence of the breach of contract as could have been fairly and reasonably contemplated by both the parties when they made this contract.”

The long shadow of that broken shaft was most recently seen in Signature Indus. Services, LLC v. Int’l Paper Co., which held: “The law does not charge contracting parties with a duty to understand how their actions will affect the counterparty’s market valuation. … As a general rule, neither the counterparty’s market value nor the impact of breach on that value will be reasonably foreseeable at the time of contracting. SIS … attempted to show that IP was intimately familiar with SIS’s business because of the companies’ close relationship. But again, knowledge of a business is not the same as knowledge of the market for buying and selling that business.” No. 20-0396 (Jan. 14, 2022).

The supreme court engaged fundamental, black-letter principles of contract law in Angel v. Tauch, No. 19-0793 (Jan. 14, 2022), holding:

The supreme court engaged fundamental, black-letter principles of contract law in Angel v. Tauch, No. 19-0793 (Jan. 14, 2022), holding:

“Offer and acceptance are essential elements of a valid and binding contract. As a matter of blackletter law, an offer empowers the offeree to seal the bargain by accepting the offer. But equally well-established is the rule that acceptance is ineffective to form a binding contract if the power of acceptance has been terminated, such as by the offeror’s revocation before acceptance. The main issue in this contract dispute is whether a purported offer to settle a debt for a reduced sum was accepted before it was revoked. Resolution of that issue turns on the parameters of the recognized, but rarely implicated, doctrine of implied revocation.

Here, the parties dispute whether the implied-revocation doctrine (1) is limited to offers involving the sale of land, (2) applies if the offeree learns about the offeror’s inconsistent act from someone other than the offeror, and (3) is satisfied under the undisputed facts in this case. We hold that the doctrine is not constrained to real-property transactions and the settlement offer was impliedly revoked when the offeror assigned the underlying judgment to a third party for collection and the assignee gave the offeree a copy of the assignment agreement before he accepted the settlement offer. We therefore reverse the court of appeals’ judgment and render judgment that no contract to settle the debt was formed.”(footnotes and citations omitted, emphasis added).

(This is a crosspost from 600Hemphill.) The Energizer Bunny, famously, keeps on going. Not so, the contract between Pura-Flo and Donald Clanton, under which Pura-Flo committed to pay Clanton a monthly fee for the use of fifty water coolers. The supreme court reversed and rendered as to an award of future damages in a lawsuit between them, observing:

(This is a crosspost from 600Hemphill.) The Energizer Bunny, famously, keeps on going. Not so, the contract between Pura-Flo and Donald Clanton, under which Pura-Flo committed to pay Clanton a monthly fee for the use of fifty water coolers. The supreme court reversed and rendered as to an award of future damages in a lawsuit between them, observing:

“Here, no evidence indicated the contract would endure for any length of time, let alone five years after trial. Perhaps, as the court of appeals suggested, the jury sought to award Clanton either the amount Vanderzyden originally paid Pura-Flo to buy the water coolers in 1994 or the amount Pura-Flo’s investment proposal claimed the company would pay to repurchase the water coolers after sixty months. But neither suggested rationale can be the basis for an award of future damages, which, as evidenced by its name, is an award for damages that Clanton was reasonably certain to incur in the future. Without evidence that the contract would continue in the future, the jury’s $50,000 future-damages award has no reasonable basis in evidence and therefore was not reasonably certain as required by law.”

Pura-Flo Corp. v. Clanton, No. 20-0964 (Nov. 19, 2021) (per curiam) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

“‘”Breach’” of a contract occurs when a party fails to perform an act that it has contractually promised to perform.’ Under terms of the agreement, Hinojosa merely agreed to allow the first $258,996.16 in proceeds from the sale to go to LaFredo with any remaining proceeds to be split between them. LaFredo does not identify any action taken by Hinojosa that precluded him from receiving any of the proceeds from the sale. To the contrary, the record before us suggests LaFredo received all the available proceeds, used a portion to pay for the Canton Street condominium, and signed a settlement statement reflecting his agreement to this disbursement. That LaFredo spent a portion of the proceeds to purchase the Canton Street condominium is not evidence, much less conclusive evidence, that Hinojosa breached the One Arts Plaza Agreement. Based on the record before us, we conclude LaFredo has not conclusively shown, as he must, that Hinojosa breached the One Arts Plaza Agreement.” Hinojosa v. LaFredo, No. 05-20-00166-CV (Sept. 20, 2021) (emphasis added).

“‘”Breach’” of a contract occurs when a party fails to perform an act that it has contractually promised to perform.’ Under terms of the agreement, Hinojosa merely agreed to allow the first $258,996.16 in proceeds from the sale to go to LaFredo with any remaining proceeds to be split between them. LaFredo does not identify any action taken by Hinojosa that precluded him from receiving any of the proceeds from the sale. To the contrary, the record before us suggests LaFredo received all the available proceeds, used a portion to pay for the Canton Street condominium, and signed a settlement statement reflecting his agreement to this disbursement. That LaFredo spent a portion of the proceeds to purchase the Canton Street condominium is not evidence, much less conclusive evidence, that Hinojosa breached the One Arts Plaza Agreement. Based on the record before us, we conclude LaFredo has not conclusively shown, as he must, that Hinojosa breached the One Arts Plaza Agreement.” Hinojosa v. LaFredo, No. 05-20-00166-CV (Sept. 20, 2021) (emphasis added).

The allegedly overlapping fraud and contract claims in Benge General Contracting v. Hertz Electric were as follows:

- “Appellees’ breach-of-contract counterclaim was based on ‘enforceable agreements’ under which appellees agreed to provide ‘electrical contracting and painting services at several jobsites in North Texas’ in exchange for BGC’s promise to compensate appellees for the services.”

- “Their fraud counterclaim, as stated in appellees’ fourth amended counterclaims, was based on Dennie’s reliance [on] Benge’s allegedly false representation that he would pay for work performed by appellees ‘in exchange for the signing of lien releases.’ Appellees alleged that appellants knew the representations were false when made and omitted facts regarding Benge’s misappropriation of project funds otherwise intended to compensate appellees for work performed.”

The Fifth Court concluded: “Appellants characterize this counterclaim as fraud by omission and argue there is no evidence a special relationship to support such a claim. … The gravamen of appellees’ fraud counterclaim, however, was not that Benge fraudulently omitted information but that he fraudulently induced Dennie to sign lien waivers to obtain a payment he never intended to make; indeed, a payment already owed under the contracts. Thus, appellees stated a claim for fraudulent inducement.” No. 05-19-01506-CV (Sept. 7, 2021) (mem. op.) (later modified slightly on rehearing).

The peculiar treatment of attorneys’ fee awards against LLCs in contract cases, by the now-repealed version of CPRC § 38.001, led to the resolution of a novel issue in Benge General Contracting, LLC v. Hertz Elec., LLC: “Absent mandatory, or at least persuasive, authority applying the alter-ego theory to hold an LLC’s members liable for attorney’s fees that could not be incurred by the LLC, we must abide by the plain statutory language. Accordingly, we conclude that the trial court abused its discretion in awarding attorney’s fees, and we sustain appellants’ first issue.” No. 05-19-01506-CV (Sept. 7, 2021) (mem. op.).

- In 2019, Bombardier Aerospace Corp. v. SPEP Aircraft Holdings holds that the written word matters: “Under our strongly held principles of freedom to contract, we hold that the limitation-of-liability clauses are valid limited warranties that were the basis of the parties’ bargain. … Although Bombardier’s conduct in failing to provide SPEP and PE with the new engines they bargained for was reprehensible, the parties bargained to limit punitive damages, and we must hold them to that bargain.”

- In 2020, Energy Transfer v. Enterprise emphasized that the written word matters: “We hold that parties can conclusively negate the formation of a partnership under Chapter 152 of the TBOC through contractual conditions precedent. ETP and Enterprise did so as a matter of law here, and there is no evidence that Enterprise waived the conditions.”

- During 2021, in In re the Estate of Johnson, the Court noted that actions also matter: “MacNerland was put to an election: either seek to set the will aside or accept the benefits Johnson bequeathed to her. She chose the latter. As a result, she ‘must adopt the whole contents of the instrument, so far as it concerns [her], conforming to its provisions, and renouncing every right inconsistent with it.’ Because MacNerland accepted benefits under Johnson’s will, the trial court properly dismissed her challenge to its validity.” (citation omitted).

- But last week, in BPX Operating v. Strickhausen, the Court again gave primacy to the written word: “Strickhausen bargained for a strong anti-pooling clause, she consistently withheld the written consent the clause requires, and she reiterated her objections multiple times. Although she accepted BPX’s money, she reasonably believed that one way or another she was owed an amount in the same ballpark as the checks she deposited.”

The Fifth Court had good news, and bad news, for the plaintiff suing for breach of an alleged oral contract in Midwest Compressor Systems v. Highland Imperial, Inc.:

The Fifth Court had good news, and bad news, for the plaintiff suing for breach of an alleged oral contract in Midwest Compressor Systems v. Highland Imperial, Inc.:

GOOD NEWS: “Gerber testified not only that Prince solicited the compressors and urged him to deliver them quickly, but also testified about Highland’s receipt and use of the compressors. This evidence creates at least a question of fact regarding the existence of oral leases. See Tex. Bus. & Com. Code § 2A.204(a) (‘A lease contract may be made in any manner sufficient to show agreement, including conduct by both parties which recognizes the existence of a lease contract.’)”.

BAD NEWS: “Midwest did not bill in advance for each day of Highland’s use; it billed in arrears for the 30 days’ use that had already occurred. Hence an invoice dated June 30 expressly stated it was for ‘June compressor rental.’ Thus, although the amount required for each lease could have been less than $1,000 if the leases had terminated after one day, each lease on which Midwest sought payment continued for thirty days and Midwest admitted the total amount fell within the statute [of frauds.]” No. 05-19-01115-CV (June 22, 2021) (mem. op.).

The issue: “[W]hether the word ‘predecessors’ in the Release’s phrase “[Headington] waives, releases, acquits and discharges Petro Canyon and its affiliates and their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees, agents, predecessors and representatives for any liabilities, claims, . . . [and] causes of action . . . related in any way to the Loving County Tract” refers to (i) Petro Canyon and its affiliates’ corporate entities and agents (‘Players’) or (ii) prior parties in Petro Canyon’s chain of title (‘Spectators’) that are otherwise unrelated to Petro Canyon.”

The issue: “[W]hether the word ‘predecessors’ in the Release’s phrase “[Headington] waives, releases, acquits and discharges Petro Canyon and its affiliates and their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees, agents, predecessors and representatives for any liabilities, claims, . . . [and] causes of action . . . related in any way to the Loving County Tract” refers to (i) Petro Canyon and its affiliates’ corporate entities and agents (‘Players’) or (ii) prior parties in Petro Canyon’s chain of title (‘Spectators’) that are otherwise unrelated to Petro Canyon.”

Held: “‘[P]redecessors’ is in a string of entity-related groups (‘Players’), not chain of title-related owners of the real property interest (‘Spectators’). Excluding ‘predecessor,’

each of those other terms in the Release relate as ‘birds of a feather’ to the corporate

composition or structure of Petro Canyon and its affiliates. The placement of the

term ‘predecessors’ along with its ordinary meaning gives the term a certain legal

meaning.”

Dissent: “The majority’s interpretation of the term “predecessors” in the Release fails to acknowledge the context of the circumstances surrounding the PCH Agreement, including the events leading to its formation, the relationships of the parties, each party’s motivations for entering the agreement, and the intentions of the parties as expressed in the agreement. The majority’s interpretation of the Release also impermissibly adds language to the Release, and the majority opinion conflicts with this Court’s prior opinions.” Headington Royalty v. Finley Resources, No. 05-19-00291-CV (March 18, 2021).

In Anubis Pictures LLC v. Selig, a dispute about the development of a screenplay, two terms from an early-stage NDA were key to resolving it:

In Anubis Pictures LLC v. Selig, a dispute about the development of a screenplay, two terms from an early-stage NDA were key to resolving it:

As to the parties’ relationship: “Neither party is bound to proceed with any transaction between the parties unless and until both parties sign a formal, written agreement setting forth the terms of such transaction. At any time prior to the completion of such a formal, written agreement, either party may terminate the Discussions and refuse to enter into any subsequent transaction, for any reason or for no reason, without liability for such termination, even if the other performed work or incurred expenses related to a potential transaction in anticipation that the parties would enter into a formal, written agreement regarding such transaction.”

As to the documents shared: “To be covered under the terms of the NDA, confidential information disclosed in written form was required to be marked confidential on its face. Any oral statement intended to be confidential had to be clearly designated as such by the disclosing party.” No. 05-19-00817-CV (March 3, 2021) (mem. op.).

Gharavi owned a business that won an arbitration against Khademazad. Gharavi sued to enforce the award, and along the way, made a comment about Khademazad and the award on Yelp. The parties resolved their differences and entered a settlement agreement of the lawsuit about the award, in which Khademazad released all claims “directly or indirectly attributable to the transaction or occurences made the basis of this lawsuit.” Several weeks later, Khademazad sued for libel and similar claims based on the Yelp post. The Fifth Court found that this suit was barred by the release: “Without question, the Yelp review was, if not directly, then indirectly attributable to Khademazad’s failure to pay for Aidris’s services and the lawsuit that followed. Khademazad’s claims here are clearly within the subject matter of the release.” Gharavi v. Khademazad, No. 05-20-00083-CV (Feb. 2, 2021) (mem. op.).

Among other issues addressed in Wal-Mart Stores v. Xerox State & Local Solutions, Inc., the Fifth Court examined whether indemnity obligations can give rise to third-party beneficiary status, and concluded that they did not on this record. No. 05-18-01421-CV (Nov. 12, 2020) (mem. op.). (LPHS represented Xerox, the successful appellee.)

After an earlier dispute about the merits of an interlocutory stay, the Fifth Court reached the substantive issue of arbitrability in Baby Dolls v. Sotero, a personal-injury lawsuit about a serious car accident involving two dancers after they left work. The key question was the interplay of the terms “License” and “Agreement” in the relevant contract; the panel majority concluded: “On this record, we conclude the trial court could have properly determined the parties’ minds could not have met regarding the contract’s subject matter and all its essential terms such that the contract is not an enforceable agreement. Consequently, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by denying the motions to compel arbitration.” (citations omitted). A dissent disputed whether that conclusion was a proper legal basis to deny a motion to compel arbitration, and would have reached a different result about the construction of the parties’ contract. No. 05-19-01443-CV (Aug. 21, 2020) (mem. op.)

After an earlier dispute about the merits of an interlocutory stay, the Fifth Court reached the substantive issue of arbitrability in Baby Dolls v. Sotero, a personal-injury lawsuit about a serious car accident involving two dancers after they left work. The key question was the interplay of the terms “License” and “Agreement” in the relevant contract; the panel majority concluded: “On this record, we conclude the trial court could have properly determined the parties’ minds could not have met regarding the contract’s subject matter and all its essential terms such that the contract is not an enforceable agreement. Consequently, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by denying the motions to compel arbitration.” (citations omitted). A dissent disputed whether that conclusion was a proper legal basis to deny a motion to compel arbitration, and would have reached a different result about the construction of the parties’ contract. No. 05-19-01443-CV (Aug. 21, 2020) (mem. op.)

“[Tex. R. Civ. P.] 11 provides that ‘no agreement between attorneys or parties touching any suit pending will be enforced unless it be in writing, signed and filed with the papers as part of the record, or unless it be made in open court and entered of record.’ The purpose of the rule is to relieve the courts of the necessity of resolving disputes over the terms of oral agreements relating to pending suits. As explained in [Anderson v. Cocheu], however, in enforcing rule 11 [agreements] ‘the Texas Supreme Court has been mindful of the fact that the rule may be said to abridge the substantive right of persons to enter into oral contracts.’ Consequently, courts have balanced the purpose of the rule with the ability to make oral agreements, resulting in recognition of certain equitable exceptions to rule 11’s writing requirement. One exception to the writing requirement arises when the oral agreement is undisputed. ‘In cases where the existence of the agreement and its terms are not disputed, the agreement may be enforced despite its literal noncompliance with the rule.’” In re Estate of Powell, No. 05-19-00689-CV (Aug. 4, 2020) (mem. op.).

“[Tex. R. Civ. P.] 11 provides that ‘no agreement between attorneys or parties touching any suit pending will be enforced unless it be in writing, signed and filed with the papers as part of the record, or unless it be made in open court and entered of record.’ The purpose of the rule is to relieve the courts of the necessity of resolving disputes over the terms of oral agreements relating to pending suits. As explained in [Anderson v. Cocheu], however, in enforcing rule 11 [agreements] ‘the Texas Supreme Court has been mindful of the fact that the rule may be said to abridge the substantive right of persons to enter into oral contracts.’ Consequently, courts have balanced the purpose of the rule with the ability to make oral agreements, resulting in recognition of certain equitable exceptions to rule 11’s writing requirement. One exception to the writing requirement arises when the oral agreement is undisputed. ‘In cases where the existence of the agreement and its terms are not disputed, the agreement may be enforced despite its literal noncompliance with the rule.’” In re Estate of Powell, No. 05-19-00689-CV (Aug. 4, 2020) (mem. op.).

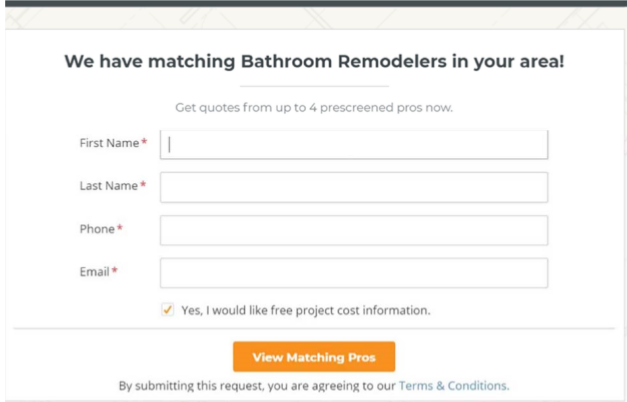

The philosophy of aesthetics finds practical application in the law of website user agreements, as illustrated in Home Advisor, Inc. v. Waddell. The plaintiffs sought to avoid arbitration of their claims, arguing that the notice about “terms and conditions” on this screen was not sufficiently conspicuous:

The Fifth Court disagreed. Citing the recent Northern District of Texas opinion in Phillips v. Neutron Holdings, the Court noted a distinction among “clickwrap” agreements, “browsewrap” agreements, and “sign-in-wrap” agreements. This case involved a sign-in wrap agreement, which “notifies the user of the existence of the website’s terms and conditions and advises the user that he or she is agreeing to the terms when registering an account or signing up,” and is “typically enforce[d] . . . when notice of the existence of the te rms was ‘reasonably conspicuous.'” The Court found that this agreement was conspicuous enough, noting that “more cluttered and complicated sign-in-wrap screens have been found to provide sufficient notice” of similar contract terms. No. 05-19-00669-CV (June 4, 2020) (mem. op.)

rms was ‘reasonably conspicuous.'” The Court found that this agreement was conspicuous enough, noting that “more cluttered and complicated sign-in-wrap screens have been found to provide sufficient notice” of similar contract terms. No. 05-19-00669-CV (June 4, 2020) (mem. op.)

Pennington, Fields, and Phillips each owned 1/3 of the shares of Advantage Marketing & Labeling, Inc. Pennington argued that under their shareholder agreement he other two were required to buy his stock when he decided to sell his full interest and become a “retiring shareholder” under that agreement. Fields and Phillips resisted, pointing out that Pennington was employed by another business when he made his

Pennington, Fields, and Phillips each owned 1/3 of the shares of Advantage Marketing & Labeling, Inc. Pennington argued that under their shareholder agreement he other two were required to buy his stock when he decided to sell his full interest and become a “retiring shareholder” under that agreement. Fields and Phillips resisted, pointing out that Pennington was employed by another business when he made his  demand; thus, “because he was not ‘retired’ from any and all employment, he could not be a ‘retiring shareholder’ for purposes of the CPA.” The Fifth Court disagreed based on two basic contract-construction principles: “This construction . . . assigns a definition to only one of the two words the parties used to describe who must comply with the paragraph’s provisions. It also disregards the context. The paragraph imposes requirements for the disposition of shares by a ‘retiring shareholder’ in the context of an agreement that imposes restrictions on stock transfer.” Pennington v. Fields, No. 05-19-00149-CV (May 22, 2020) (mem. op.)

demand; thus, “because he was not ‘retired’ from any and all employment, he could not be a ‘retiring shareholder’ for purposes of the CPA.” The Fifth Court disagreed based on two basic contract-construction principles: “This construction . . . assigns a definition to only one of the two words the parties used to describe who must comply with the paragraph’s provisions. It also disregards the context. The paragraph imposes requirements for the disposition of shares by a ‘retiring shareholder’ in the context of an agreement that imposes restrictions on stock transfer.” Pennington v. Fields, No. 05-19-00149-CV (May 22, 2020) (mem. op.)

The tenants in a residential lease sued for injuries from toxic mold on the property. The Fifth Court expressed sympathy, but nevertheless affirmed summary judgment for the landlord based on an “as is” clause in the lease, citing Prudential Ins. Co. v. Jefferson Assocs. 896 S.W.2d 156 (Tex. 1995). In addition to noting that the clause was prominently written in all-caps, and consistent with other related provisions in the lease, the Court observed: ‘Before they entered into the Lease and related agreements, Rebecca walked through the house twice and Richard walked through the house once. After signing the Lease but prior to moving in, the Potters visited the house again and saw “black substance” on the wall and coming out of a wall socket. Rebecca testified she saw “bubbling” and “deforming” of a wall that, according to a workman, was caused by “clogged gutters.” In a subsequent visit prior to moving in, Richard saw “black underneath the carpet” being removed by a carpet repairman. When they were told by workmen the black substance was dirt and dog feces, the Potters did not further investigate.’ Potter v. HP Texas 1 LLC, No. No. 05-18-01513-CV (Apr. 6, 2019) (mem. op.)

The tenants in a residential lease sued for injuries from toxic mold on the property. The Fifth Court expressed sympathy, but nevertheless affirmed summary judgment for the landlord based on an “as is” clause in the lease, citing Prudential Ins. Co. v. Jefferson Assocs. 896 S.W.2d 156 (Tex. 1995). In addition to noting that the clause was prominently written in all-caps, and consistent with other related provisions in the lease, the Court observed: ‘Before they entered into the Lease and related agreements, Rebecca walked through the house twice and Richard walked through the house once. After signing the Lease but prior to moving in, the Potters visited the house again and saw “black substance” on the wall and coming out of a wall socket. Rebecca testified she saw “bubbling” and “deforming” of a wall that, according to a workman, was caused by “clogged gutters.” In a subsequent visit prior to moving in, Richard saw “black underneath the carpet” being removed by a carpet repairman. When they were told by workmen the black substance was dirt and dog feces, the Potters did not further investigate.’ Potter v. HP Texas 1 LLC, No. No. 05-18-01513-CV (Apr. 6, 2019) (mem. op.)

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

- the performance issue was a basic assumption of the contract;

- the government’s action was an official order or regulation (in that case, the SEC’s contact with the defendant was not); and

- the defendant was acting in good faith.

The Court relied on an earlier Texas Supreme Court case and the relevant Restatement (Second) of Contracts provision. Application of this opinion will be important in upcoming commercial disputes created by the novel coronavirus.

“The contract, which neither side contends is ambiguous, bears Mr. Turnbow’s signature and does not mention PMC Chase or indicate representative capacity in any way. Thus, on its face, the contract unambiguously shows it is the obligation of Mr.Turnbow personally.” Accordingly, among other reasons, judgment against Mr. Turnbow was affirmed. PMC Chase, LLP v. Branch Structural Solutions, Inc., No. 05-18-01383-CV (Jan. 28, 2020) (mem. op.).

“The contract, which neither side contends is ambiguous, bears Mr. Turnbow’s signature and does not mention PMC Chase or indicate representative capacity in any way. Thus, on its face, the contract unambiguously shows it is the obligation of Mr.Turnbow personally.” Accordingly, among other reasons, judgment against Mr. Turnbow was affirmed. PMC Chase, LLP v. Branch Structural Solutions, Inc., No. 05-18-01383-CV (Jan. 28, 2020) (mem. op.).

In Energy Transfer Partners v. Enterprise Products Partners, the Texas Supreme Court resolves a Texas-sized partnership dispute in favor of contractual waivers of partnership. No. 17-0862 (Tex. Jan. 31, 2020). The underlying case arose from a $550 million judgment entered in 2014 in Dallas County, later reversed by the Dallas Court of Appeals; this opinion affirms the Fifth Court’s judgment.

The parties’ contract had a 4-year term:

The parties’ contract had a 4-year term:

“Subject to jcpenny’s rights to relocate or otherwise change or alter the shops as specified below, the parties agree that the Bodum and O&R Shops will be featured in the designated jcpenny stores for a period of 4 years from the opening date . . .”

But, the “rights . . . specified below” included the right to:

remove, alter, or relocate any and all Bodum or O&R Shops or any portion of a Bodum or O&R Shop. . .

Accordingly, the contract was terminable at will. Bodum USA, Inc. v. J.C. Penney Co., No. 05-18-00813-CV (Oct. 23, 2019) (The opinion has a thorough discussion of Texas contract-interpretation principles, including a reminder that contra proferentum “is a doctrine of last resort.” Substantively, the parties do not appear to have argued whether this termination right made the contract illusory.)

CExchange sold several thousand used headphones and speakers to Top Wireless. Top Wireless complained about the quality of the goods; CE Exchange defended by reference to an “as is” clause in their contract documents. The Fifth Court found that the clause did not preclude Top Wireless’s claims and affirmed a jury verdict in its favor, noting:

CExchange sold several thousand used headphones and speakers to Top Wireless. Top Wireless complained about the quality of the goods; CE Exchange defended by reference to an “as is” clause in their contract documents. The Fifth Court found that the clause did not preclude Top Wireless’s claims and affirmed a jury verdict in its favor, noting:

- The jury’s finding on a contract-formation question “amounts to a determination that the ‘as is’ clause was not an operative part of the subject agreement”; and

- Alternatively, other jury findings established the fraudulent-inducement exception to the enforceability of such a clause, citing Prudential Ins. v. Jefferson Assocs., 896 S.W.2d 156 (Tex. 1995).

CExchange, LLC v. Top Wireless Wholesaler, No. 05-17-01318-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.).

The recent Texas Supreme Court case of Pathfinder Oil & Gas v. Great Western Drilling reminds: “Parties can . . . waive their right to proof of a fact or an element of a claim through a written stipulation or one made in open court.” No. 18-0186 (Tex. May 24, 2019). Such agreements, commonly called “Rule 11 Agreements” in Texas practice for the relevant state rule of civil procedure, are “contracts relating to litigation” and are “construe[d] . . . under the same rules as a contract.” The more challenging question about a challenge to formation of such an agreement, rather than its interpretation, is the subject of a recent article that I co-authored in a State Bar Litigation Section publication.

The recent Texas Supreme Court case of Pathfinder Oil & Gas v. Great Western Drilling reminds: “Parties can . . . waive their right to proof of a fact or an element of a claim through a written stipulation or one made in open court.” No. 18-0186 (Tex. May 24, 2019). Such agreements, commonly called “Rule 11 Agreements” in Texas practice for the relevant state rule of civil procedure, are “contracts relating to litigation” and are “construe[d] . . . under the same rules as a contract.” The more challenging question about a challenge to formation of such an agreement, rather than its interpretation, is the subject of a recent article that I co-authored in a State Bar Litigation Section publication.

BCH Development sought to build a two-story house; the neighborhood association sued to enforce a restrictive covenant limiting construction to a “single family dwelling not to exceed one story in height.” Because a two-story house stood on the neighboring lot, BCH argued waiver; the association countered that 1 nonconforming lot out of 104 could not establish waiver. The Fifth Court remanded for trial on the issue of waiver, noting: “Waiver in restrictive covenant cases is a fact-intensive inquiry involving multiple factors. A statistical analysis is but one component in determining the issue of waiver. Also relevant are the nature and severity of existing violations, any prior acts of enforcement of the restriction, and whether it is still possible to realize to a substantial degree the benefits intended through the covenant.” BCH Development v. Lakeview Heights Addition Property Owners’ Assoc., No. 05-17-01096-CV (March 21, 2019). Notably, the opinion was decided by a 2-judge panel of Justices Myers and Brown, after Justice Evans was not re-elected in 2018.

BCH Development sought to build a two-story house; the neighborhood association sued to enforce a restrictive covenant limiting construction to a “single family dwelling not to exceed one story in height.” Because a two-story house stood on the neighboring lot, BCH argued waiver; the association countered that 1 nonconforming lot out of 104 could not establish waiver. The Fifth Court remanded for trial on the issue of waiver, noting: “Waiver in restrictive covenant cases is a fact-intensive inquiry involving multiple factors. A statistical analysis is but one component in determining the issue of waiver. Also relevant are the nature and severity of existing violations, any prior acts of enforcement of the restriction, and whether it is still possible to realize to a substantial degree the benefits intended through the covenant.” BCH Development v. Lakeview Heights Addition Property Owners’ Assoc., No. 05-17-01096-CV (March 21, 2019). Notably, the opinion was decided by a 2-judge panel of Justices Myers and Brown, after Justice Evans was not re-elected in 2018.

LaFrance argued that he was not personally liable for a contract debt. But – “LaFrance signed his name on the agreement’s signature line labeled Borrower’s Signature.’ He did not indicate a representative capacity. In the section titled ‘Liability,’ the agreement states, ‘Although this agreement may be signed below by more than one person, each of the undersigned understands that they are each as individuals responsible and jointly and severally liable for paying back the full amount.’ Because the agreement’s language can be given a definite legal meaning and is not reasonably susceptible to more than one interpretation, the agreement is unambiguous.” EcoFriendly Water Co. v. Mercer, No. 05-18-00763-CV (May 2, 2019) (mem. op.).

LaFrance argued that he was not personally liable for a contract debt. But – “LaFrance signed his name on the agreement’s signature line labeled Borrower’s Signature.’ He did not indicate a representative capacity. In the section titled ‘Liability,’ the agreement states, ‘Although this agreement may be signed below by more than one person, each of the undersigned understands that they are each as individuals responsible and jointly and severally liable for paying back the full amount.’ Because the agreement’s language can be given a definite legal meaning and is not reasonably susceptible to more than one interpretation, the agreement is unambiguous.” EcoFriendly Water Co. v. Mercer, No. 05-18-00763-CV (May 2, 2019) (mem. op.).

Footnote 11 of the Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in West v. Quintanilla clarified the two distinct doctrines, each of which is commonly referred to as “the parol evidence rule”: “The contract-construction rule applies when a contract is written and unambiguous, and it prohibits consideration of oral or extrinsic evidence to modify or add to the contract’s terms. ‘[T]he construction of an unambiguous contract, including the determination of whether it is unambiguous, depends on the language of the contract itself, construed in light of the surrounding circumstances.’ By contrast, the parol evidence rule applies when a contract is written and integrated, and it precludes enforcement of any prior or contemporaneous agreement that is inconsistent with the written contract’s terms.” No. 17-0454 (Tex. Apr. 5, 2019) (citations omitted).

Footnote 11 of the Texas Supreme Court’s recent opinion in West v. Quintanilla clarified the two distinct doctrines, each of which is commonly referred to as “the parol evidence rule”: “The contract-construction rule applies when a contract is written and unambiguous, and it prohibits consideration of oral or extrinsic evidence to modify or add to the contract’s terms. ‘[T]he construction of an unambiguous contract, including the determination of whether it is unambiguous, depends on the language of the contract itself, construed in light of the surrounding circumstances.’ By contrast, the parol evidence rule applies when a contract is written and integrated, and it precludes enforcement of any prior or contemporaneous agreement that is inconsistent with the written contract’s terms.” No. 17-0454 (Tex. Apr. 5, 2019) (citations omitted).

In its third case this term about the effect of contractual disclaimers in commercial disputes, the Texas Supreme Court held:

In its third case this term about the effect of contractual disclaimers in commercial disputes, the Texas Supreme Court held:

‘We have no trouble concluding that the factors generally support a finding that Lufkin effectively disclaimed reliance on IBM’s misrepresentations. The parties negotiated the Statement of Work at arm’s length, they were both knowledgeable in business matters and represented by counsel, and the two clauses expressly and clearly disclaim reliance. But as Lufkin points out, the clauses only disclaim reliance on representations that are “not specified” in the Statement of Work or the Customer Agreement. Relying on two other provisions, Lufkin argues that the misrepresentations on which it based its fraudulent-inducement claim were “specified” in the Statement of Work, and at a minimum, reading those provisions together with the disclaimers’ “not specified” language renders the clauses too ambiguous to be enforceable. We are not convinced.‘

Encompass Office Solutions v. Blue Cross & Blue Shield of Louisiana, No. 17-0666 (Tex. March 15, 2019).

Morben Realty successfully sued Texas Capital Holdings; the trial court denied recover of attorneys’ fees and the Fifth Court reversed, noting: “Texas law has ‘long distinguished attorneys’ fees from damages.’ So does this contract.” Specifically, the section on remedies “generally provides the seller with a liquidated damages remedy if the purchaser defaults” –

Morben Realty successfully sued Texas Capital Holdings; the trial court denied recover of attorneys’ fees and the Fifth Court reversed, noting: “Texas law has ‘long distinguished attorneys’ fees from damages.’ So does this contract.” Specifically, the section on remedies “generally provides the seller with a liquidated damages remedy if the purchaser defaults” –

Seller shall, as Seller’s sole remedy, be entitled to terminate this Contract and receive and retains the Earnest Money deposit as liquidated damages; it being specifically agreed between Seller and Purchaser that Seller’s actual damages in the event of Purchaser’s default would be impossible to ascertain and the Earnest Money Deposit is a reasonable estimate of the same . . . .

But another section addressed the recovery of fees by the prevailing party –

In the event either party to this Contract commences legal action of any kind to enforce the terms and conditions of this Contract, the prevailing party in such litigation shall be entitled to collect from the other party all reasonable costs, expenses, and attorney’s fees incurred in connection with such action.

Morben Realty v. Texas Capital Holdings, No. 05-17-01105-CV (Feb. 27, 2019) (mem. op.)