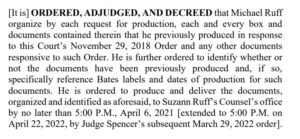

In re Ruff found that an order was too vague to enforce by contempt. The order involved discovery obligations and the relevant paragraph was as follows:

The Fifth Court held: “[R]reasonable people could come to different conclusions as to what relator was supposed to do in order to comply with this provision of the March 23, 2021 order. Consequently, that provision is too unclear to support a judgment of contempt.” Specifically:

- How to comply? “The first sentence of the provision requires him to “organize” both (i) boxes and documents that he previously produced in response to the court’s November 29, 2018 order and (ii) any other documents responsive to that order. It is unclear how relator is supposed to “organize” the category (i) materials because those materials—boxes and documents that he previously produced in response to a specific court order—are by definition no longer in his possession.”

- What documents? And category (ii) of this first sentence is ambiguous because it is not clear whether this category of “other documents responsive” to the court’s November 29, 2018 order is limited to documents that relator had previously produced in this litigation or whether it also extends to unproduced documents.”

- How to comply, and what documents? “Finally, the last sentence of the provision requires relator to “produce and deliver the documents, organized and identified as aforesaid.” This requirement is also unclear. As noted above, the provision directs relator to organize the boxes and documents that relator had already produced in response to the court’s November 29, 2018 order. Those are specific, existing materials that by definition are no longer in his possession. But the last sentence of the provision implies, contrary to the first sentence, that relator is supposed to produce and deliver a new collection of “organized and identified” materials to RPI’s attorney.”