The picayune, yet longstanding, distinction in Texas jury-charge practice between “objecting” and “requesting” jury questions/instructions reared its head again in Shawnee Inc. v. Kaz Meyers Properties, LLC. There, a request for an instruction about mitigation of damages was held insufficient to preserve error, even though the text of the requested instruction was dictated into the record. No. 05-23-00507-CV (July 10, 2025) (mem. op.).

The picayune, yet longstanding, distinction in Texas jury-charge practice between “objecting” and “requesting” jury questions/instructions reared its head again in Shawnee Inc. v. Kaz Meyers Properties, LLC. There, a request for an instruction about mitigation of damages was held insufficient to preserve error, even though the text of the requested instruction was dictated into the record. No. 05-23-00507-CV (July 10, 2025) (mem. op.).

Category Archives: Jury Charge

In Santander Consumer USA Inc. v. Enterprise Fin. Group, Inc., the Fifth Court addressed preservation of charge error.

In Santander Consumer USA Inc. v. Enterprise Fin. Group, Inc., the Fifth Court addressed preservation of charge error.

Specifically, the Court held that the appellant failed to object specifically to the broad form submission of Question No. 1, which asked if the appellant failed to comply with the agreement. It observed that the appellant “did not object to the submission of Question No. 1 at the charge conference or before the charge was read to the jury,” and reminded that submitting a proposed charge or jury questions pretrial is not enough to preserve a charge-error issue.

Importantly, this analysis means that “[t]he use of a global denial of objections and requests based solely on the parties’ pretrial submission of proposed jury charges does not preserve issues of charge error for appellate review.” No. 23-0770-CV (Dec. 31, 2024) (mem. op.).

In Baylor Scott & White v. Bostick, the Fifth Court reversed the trial court’s judgment due to errors in the jury charge regarding the definition of an invitee. The Court found that the trial court improperly included the “public invitee” component in the definition of an invitee, which is not recognized under Texas law. The correct definition, as established by the Texas Supreme Court, is that an invitee is “one who enters the property of another with the owner’s knowledge and for the mutual benefit of both,” with the requisite mutual benefit being a shared business or economic interest.

In Baylor Scott & White v. Bostick, the Fifth Court reversed the trial court’s judgment due to errors in the jury charge regarding the definition of an invitee. The Court found that the trial court improperly included the “public invitee” component in the definition of an invitee, which is not recognized under Texas law. The correct definition, as established by the Texas Supreme Court, is that an invitee is “one who enters the property of another with the owner’s knowledge and for the mutual benefit of both,” with the requisite mutual benefit being a shared business or economic interest.

The Court went on to hold that the error in the jury charge was harmful because it related to a contested and critical issue—the plaintiff’s status as an invitee. The evidence was sharply conflicting on this point, and the improper definition let the jury find Bostick was an invitee based on the fact that he entered the hospital as a member of the public. No. 05-23-00606-CV, Dec. 6, 2024 (mem. op.).

In Horton v. Kansas City Southern Ry. Co., the Texas Supreme Court walked back a line of authority about the Casteel harmful-error presumption for certain types of charge error, stating that the presumption does not apply to legal-sufficiency issues that arise from proof failure rather than legal infirmity:

In Horton v. Kansas City Southern Ry. Co., the Texas Supreme Court walked back a line of authority about the Casteel harmful-error presumption for certain types of charge error, stating that the presumption does not apply to legal-sufficiency issues that arise from proof failure rather than legal infirmity:

For this reason, and in an effort to clarify the law and simplify the process, we hold that reviewing courts should not presume harm when a broad-form submission permits a jury to make a finding based on a theory or allegation that is invalid only because it lacks evidentiary support. Because the broad-form negligence question submitted in this case was erroneous only for that reason, we conclude that Casteel’s presumed-harm rule does not apply.

Fair enough. Now what? The court explained:

After determining whether [the Casteel presumption] applies, and assuming the parties point to the record to support their conflicting positions, reviewing courts should focus on the ultimate question of whether “a review of the entire record provides [a] clear indication that the contested charge issues probably caused the rendition of an improper judgment.” Focusing on that ultimate issue, reviewing courts should explain in their opinions why the record as a whole does or does not establish harm in each particular case.

No. 21-0769 (June 28, 2024) (citations omitted). Time will tell whether this clarification enhances the efficiencies of broad-form submission, or produces Baroque case law about various indicia of harm, since a jury’s actual thought process is privileged.

“Under [Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code] Section 41.003, a court may not imply a unanimous jury finding in imposing exemplary damages. The burden to secure a unanimous verdict is on the plaintiff and ‘may not be shifted.'” Oscar Renda Contracting, Inc. v. Bruce, No. 22-089 (Tex. May 3, 2024).

“Under [Tex. Civ. Prac. & Rem. Code] Section 41.003, a court may not imply a unanimous jury finding in imposing exemplary damages. The burden to secure a unanimous verdict is on the plaintiff and ‘may not be shifted.'” Oscar Renda Contracting, Inc. v. Bruce, No. 22-089 (Tex. May 3, 2024).

The concept of estoppel is recognized by modern Texas law in many distinct doctrines: quasi-estoppel, equitable estoppel, judicial estoppel, etc. And sometimes, just saying the right words at the right time creates an estoppel, as occurred in a recent Texas Court of Criminal Appeals opinion where this exchange occurred about a key jury instruction:

Held: “The record reflects Appellant specifically asked the trial court to ensure that the jury be instructed they had to agree ‘beyond a reasonable doubt’ that Hogarth was an accomplice. We hold that Appellant, once he stated ‘I’m good’ with the instruction, is estopped from thereafter claiming that the instruction was improper.” Ruffins v. State, No. PD-0862-10 (Tex. Crim. App. March 29, 2023). I thank my friend Doug Gladden, a keen observer of Texas criminal law, for drawing this case to my attention.

In the case of In re Commitment of Robinson, a civil-commitment case about a sexually violent individual, the trial court granted a directed verdict that the defendant was a “repeat sexually violent offender” and included an instruction to that effect in the jury charge. In a holding that likely has little effect outside this specific procedural setting, the Fifth Court found no plain error from that particular instruction in this specific case. No. 05-21-00795-CV (Feb. 23, 2023).

Newsom, Terry, & Newsom LLP v. Henry S. Miller Commercial Co. reviewed the trial of an attorney-malpractice claim based on an untimely designation of a responsible third party. The Fifth Court found reversible charge error in the following jury instruction as an impermissible comment:

Newsom, Terry, & Newsom LLP v. Henry S. Miller Commercial Co. reviewed the trial of an attorney-malpractice claim based on an untimely designation of a responsible third party. The Fifth Court found reversible charge error in the following jury instruction as an impermissible comment:

In resisting a motion to strike a designation of a responsible third party, the Terry Defendants would not have been required to prove the plaintiffs’ case that there was fraud in the underlying transaction. They could rely on evidence of the proposed transaction, its failure, and the identity of a responsible third party as the defaulting buyer in resisting a motion to strike a designation of a responsible third party.

No. 05-20-00379-CV (Aug. 31, 2022) (mem. op.).

In a defamation / business disparagement claim, when the charge told the jury to: it was reversible error for the jury to consider evidence about the effects of “a widespread ‘whisper campaign'” distinct from the referenced statement. Memorial Hermann Health System v. Gomez, No. 19-0872 (Tex. April 22, 2022).

it was reversible error for the jury to consider evidence about the effects of “a widespread ‘whisper campaign'” distinct from the referenced statement. Memorial Hermann Health System v. Gomez, No. 19-0872 (Tex. April 22, 2022).

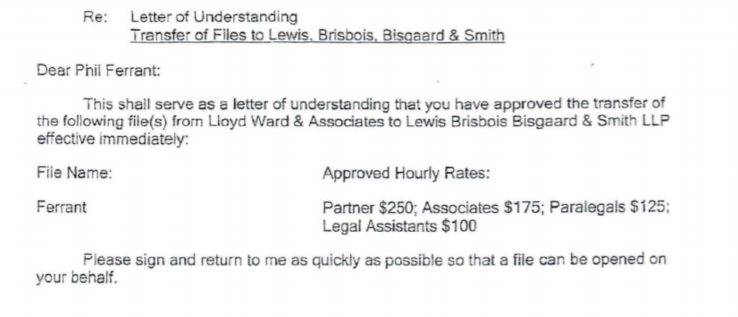

In Ferrant v. Lewis Brisbois, No. 05-19-01552-CV (July 14, 2021) (mem. op.), a law firm client contended that no evidence established his consent to an hourly billing arrangement; the Fifth Court affirmed the judgment against him based on this “acknowledgment” at the time the client moved his business from another law firm —

and a “yes” answer to this jury question:

The trial court dismissed the plaintiff’s case in Ashrat v. Choudhry as involving a dispute about rights to real property located in Pakistan. The Fifth Court disagreed, noting as to the claim:

The trial court dismissed the plaintiff’s case in Ashrat v. Choudhry as involving a dispute about rights to real property located in Pakistan. The Fifth Court disagreed, noting as to the claim:

Ashrat does not dispute that Choudhry has title to the property in Pakistan. And, by this suit, Ashrat does not seek to divest Choudhry of that title. Instead, Ashrat seeks return of the money he gave Choudhry to purchase the property and disgorgement of any monies received by Choudhry as a result of his misuse of Ashrat’s funds.

and as to forum non conveniens:

Texas courts clearly have an interest in resolving a dispute between its citizens regarding an alleged agreement made within the State and claims of misappropriation and breach of fiduciary duty based upon that alleged agreement.

No. 05-20-00515-CV (June 30, 2021) (mem. op.).

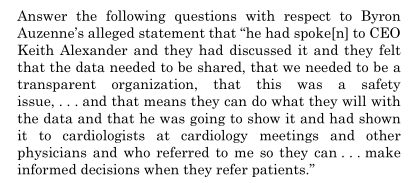

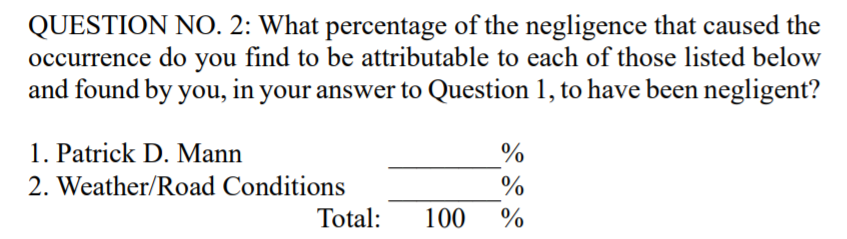

The Greeks saw the all-powerful Zeus as the god of the skies; Haitian vodou, the storm-spirit Agau; and so forth throughout all the world’s cultures. Despite that tradition, the Fifth Court reversed a jury instruction that posed the following comparative-fault question:

“Though the jury here made no finding that the occurrence was proximately caused by the acts or omissions of more than one person, question number two of the charge allowed the jury to find a ‘percentage of the negligence’ attributable to ‘Weather/Road Conditions,’ which was not a person or party whose negligence was found to have been a proximate cause. This was not consistent with section 33.003(a) or rule 277.” Panameno v. Williams, No. 05-19-01496-CV (June 1, 2021) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

“Though the jury here made no finding that the occurrence was proximately caused by the acts or omissions of more than one person, question number two of the charge allowed the jury to find a ‘percentage of the negligence’ attributable to ‘Weather/Road Conditions,’ which was not a person or party whose negligence was found to have been a proximate cause. This was not consistent with section 33.003(a) or rule 277.” Panameno v. Williams, No. 05-19-01496-CV (June 1, 2021) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

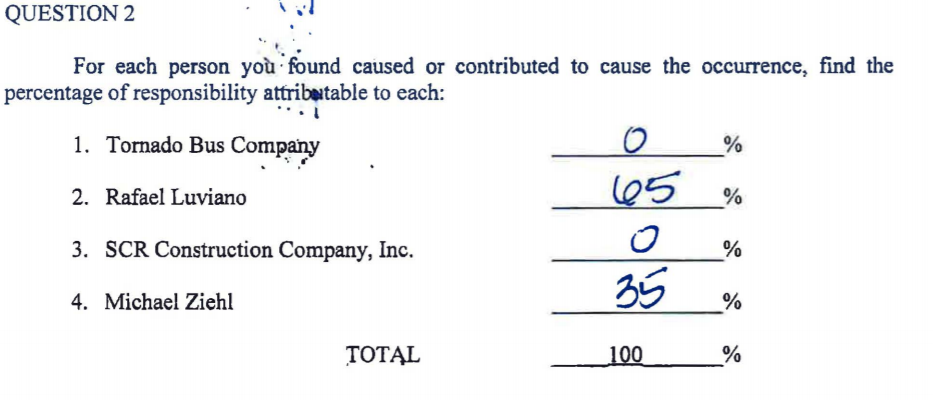

Ziehl’s car was hit by a Tornado bus, driven by Luviano. Ziehl and his passengers sued Tornado and Luviano. The jury found that Ziehl and Luviano were negligent, and that Tornado and Ziehl’s employer (SCR Construction Co.) were not. In response to the next question the jury found: From there, the court found that Luviano was entitled to contribution from Ziehl for 35% of all plaintiffs’ damages, and also reduced Ziehl’s damages by 35%.

From there, the court found that Luviano was entitled to contribution from Ziehl for 35% of all plaintiffs’ damages, and also reduced Ziehl’s damages by 35%.

The Fifth Court agreed with Ziehl that this adjustment was improper, noting: “Using the word ‘shall’ three times in [CPRC] section 33.016(c), the Legislature specifically and clearly imposed an obligation on the trier of fact to make a separate finding of the percentage of responsibility for each contribution defendant. The finding must be solely for the purpose of [CPRC] section 33.016 and cannot be part of the percentage of responsibility determined pursuant to section 33.003.” The Court reversed “[b]ecause the statute makes the question mandatory and the question was neither requested nor given ….” Ziehl v. Tornado Bus, No. 05-19-00901-CV (April 22, 2021).

A common sci-fi movie trope is the image of a “mad scientist” working in the laboratory. Texas appellate lawyers and judges have a similar look when applying Crown Life Ins. Co. v. Casteel, 22 S.W.3d 378 (2000), which deals with the vexing problem of jury charges that mix valid and invalid elements. The Fifth Court’s majority opinion in Kansas City Southern Ry. Co. v. Horton, No. 05-19-00856-CV (March 11, 2021) (mem. op.), after finding one of the plaintiffs’ two liability theories preempted by federal law, found a Casteel issue with a broad-form negligence submission in a personal injury case. It distinguished an earlier Dallas case and a Corpus Christi decision as involving factual-sufficiency rather than legal-validity issues. A dissent took issue with the holding about preemption.

A common sci-fi movie trope is the image of a “mad scientist” working in the laboratory. Texas appellate lawyers and judges have a similar look when applying Crown Life Ins. Co. v. Casteel, 22 S.W.3d 378 (2000), which deals with the vexing problem of jury charges that mix valid and invalid elements. The Fifth Court’s majority opinion in Kansas City Southern Ry. Co. v. Horton, No. 05-19-00856-CV (March 11, 2021) (mem. op.), after finding one of the plaintiffs’ two liability theories preempted by federal law, found a Casteel issue with a broad-form negligence submission in a personal injury case. It distinguished an earlier Dallas case and a Corpus Christi decision as involving factual-sufficiency rather than legal-validity issues. A dissent took issue with the holding about preemption.

Another preservation point from EYM Diner LP v. Yousef, No. 05-19-00636-CV (Nov. 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original), involves the structure of the charge on negligence. Defendant (ACCSC) complained that also argues it is entitled to rendition of judgment in its favor because the plaintiff (Youssef) did not object to the omission of  certain definitions from the charge, citing United Scaffolding v. Levine, 537 S.W.3d 463 (Tex. 2017). The Fifth Court disagreed:

certain definitions from the charge, citing United Scaffolding v. Levine, 537 S.W.3d 463 (Tex. 2017). The Fifth Court disagreed:

- “First, ACCSC’s reliance on United Scaffolding is misplaced because Yousef pleaded a general negligence claim against ACCSC and obtained a liability finding from the jury based on general negligence at trial. In United Scaffolding, the plaintiff, James Levine, pleaded one theory (premises liability) and obtained a jury finding on a different theory (general negligence).”

- “Second, United Scaffolding preserved its arguments that the verdict was based on an improper theory of recovery by filing a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict. Here, ACCSC filed no such motion and makes no such argument. ACCSC merely asserts charge error here. ACCSC waived any complaint about the charge by failing to object to the charge as discussed above. And, by failing to file a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict or other qualifying post verdict motion raising this argument, ACCSC also waived any complaint that Yousef was not entitled to obtain a jury finding as to ACCSC’s general negligence.” (emphasis added in the above).

“The trial judge in this case has a reputation for running a highly efficient courtroom in which he holds all parties to strict time limits for putting on their case. The record here shows this case was no exception. The truncated ‘charge conference’ appears to be one way in which the trial judge

moves cases along and gets cases to the jury quickly. While we applaud the trial judge’s efficiency and respect for the jurors’ time, the use of a global denial of objections and requests based solely on the parties’ pretrial submission of proposed jury charges does not preserve issues of charge error for appellate review. See, e.g., Clark v. Dillard’s, Inc., 460 S.W.3d 714, 729–30 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2015, no pet.); see also Tex. R. Civ. P. 272, 273, 274. The reason is simple; a proposed jury charge filed pretrial standing alone does not meet the preservation of error requirements of rules 272, 273, and 274.”

EYM Diner LP v. Yousef, No. 05-19-00636-CV (Nov. 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original)

I was on a panel today for a great DAYL CLE program on jury charge conferences; you can see the one-hour presentation here!

Cornwell v. Scothorn, discussed yesterday, also addressed whether quasi-estoppel could be a defense to a claimed breach of fiduciary duty. The Fifth Court affirmed on the basis of the charge submitted while also finding legally-sufficient evidence of reliance–the element that distinguishes “quasi-estoppel” from equitable estoppel. No. 05-18-00799-CV (Sept. 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

Cornwell v. Scothorn, discussed yesterday, also addressed whether quasi-estoppel could be a defense to a claimed breach of fiduciary duty. The Fifth Court affirmed on the basis of the charge submitted while also finding legally-sufficient evidence of reliance–the element that distinguishes “quasi-estoppel” from equitable estoppel. No. 05-18-00799-CV (Sept. 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

This is a cross-post from 600 Hemphill

It’s not a Texas Supreme Court case, but Title Source Inc. v. HouseCanary Inc. is a jury charge case worth reviewing. In it, the San Antonio Court of Appeals reversed a $700+ million judgment based in part on a classic Casteel issue. In reviewing the jury instruction about the plaintiff’s claim for theft of trade secrets, the Court observed:

It’s not a Texas Supreme Court case, but Title Source Inc. v. HouseCanary Inc. is a jury charge case worth reviewing. In it, the San Antonio Court of Appeals reversed a $700+ million judgment based in part on a classic Casteel issue. In reviewing the jury instruction about the plaintiff’s claim for theft of trade secrets, the Court observed:

“[T]he jury was also instructed that ‘improper means’ includes bribery, espionage, and ‘breach or inducement of a breach of a duty to maintain secrecy, to limit use, or to prohibit discovery of a trade secret.’ This instruction tracks TUTSA’s definition of ‘improper means’ and is therefore a correct statement of law. But HouseCanary conceded at oral argument that there is no evidence TSI acquired the trade secrets through bribery, and our review of the record reveals no evidence that TSI acquired the trade secrets through espionage. Because those theories are not supported by the evidence, they should have been omitted from the ‘improper means’ definition that was submitted to the jury.“

(emphasis added, citations omitted). The Court went on to cite Texas Supreme Court authority stating that while “a jury charge submitting liability under a statute should track the statutory language as closely as possible,” the statutory language “may be slightly altered to conform the issue to the evidence presented,” and that “[a] broad-form question cannot be used to put before the jury issues that have no basis in the law or the evidence.”

The jury charge in an attorney-client fee dispute asked: “Did any of the following persons form an agreement with Glast, Phillips & Murray, PC to pay for fees concerning legal representation?” The question then required the jury to answer “yes” or “no” for both of the defendants on that claim. They lost, and argued on appeal that “question one asked the jury if a contract had been formed between the parties—an issue the [defendants] argue was not in dispute—but neglected to ask whether the agreement was for payment of a flat fee or GPM’s hourly rates” (citing Lone Starr Multi-Theatres v. Max Interests, 365 S.W.3d 688 (Tex. App.–Houston [1st Dist.] 2011, no pet.)

The jury charge in an attorney-client fee dispute asked: “Did any of the following persons form an agreement with Glast, Phillips & Murray, PC to pay for fees concerning legal representation?” The question then required the jury to answer “yes” or “no” for both of the defendants on that claim. They lost, and argued on appeal that “question one asked the jury if a contract had been formed between the parties—an issue the [defendants] argue was not in dispute—but neglected to ask whether the agreement was for payment of a flat fee or GPM’s hourly rates” (citing Lone Starr Multi-Theatres v. Max Interests, 365 S.W.3d 688 (Tex. App.–Houston [1st Dist.] 2011, no pet.)

The Fifth Court found no abuse of discretion in the submission. It distinguished Lone Starr, a landlord-tenant dispute, as involving a disconnect between the jury’s damages finding and the judgment, in that “none of the questions submitted to the jury asked the amount of lost rentals suffered by the landlord, and the [jury’s] ‘fair market value’ determination did not include or even support a lost rentals determination.” Here, in contrast: “. . . in answering question four, the jury calculated GPM’s damages as the amount of GPM’s outstanding invoices, an amount derived from GPM’s hourly rates and billable hours rather than any flat fee. Accordingly, the jury necessarily rejected the Namdars’ capped fee term, and the answer to question four informs us that the jury determined the parties agreed that the Namdars would pay GPM’s hourly rates for the hours billed.” Narmarkhan v. Glast Phillips & Murray, No. 18-0802-CV (April 24, 2020) (mem. op.).

In Energy Transfer Partners v. Enterprise Products Partners, the Texas Supreme Court resolves a Texas-sized partnership dispute in favor of contractual waivers of partnership. No. 17-0862 (Tex. Jan. 31, 2020). The underlying case arose from a $550 million judgment entered in 2014 in Dallas County, later reversed by the Dallas Court of Appeals; this opinion affirms the Fifth Court’s judgment.

Denny successfully sued Chang for medical malpractice, based on a cotton ball left inside her head after brain surgery. The key appellate issue was a jury question about Denny’s “degree of diligence” in bringing suit – a finding needed to support her open courts counter-defense to the two-year statute of limitations on her claim. The majority opinion first found waiver about an objection to the form of the question, and then found that sufficient evidence supported the jury’s finding, noting testimony about her difficulty in finding a treating physician who did not “fear[] they were going to be dragged into litigation,” and that her health problems precluded her from meeting with counsel for substantial periods of time. Chang v. Denny, No. 05-17-01457-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.).

Denny successfully sued Chang for medical malpractice, based on a cotton ball left inside her head after brain surgery. The key appellate issue was a jury question about Denny’s “degree of diligence” in bringing suit – a finding needed to support her open courts counter-defense to the two-year statute of limitations on her claim. The majority opinion first found waiver about an objection to the form of the question, and then found that sufficient evidence supported the jury’s finding, noting testimony about her difficulty in finding a treating physician who did not “fear[] they were going to be dragged into litigation,” and that her health problems precluded her from meeting with counsel for substantial periods of time. Chang v. Denny, No. 05-17-01457-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.).

A dissent criticized the treatment of this issue as one of fact, warning of it “disappearing into the amorphous slurry of jury deliberations,” and that “the misunderstandings and inaction of her legal counsel” were to blame for the delay. Underlying the dissent was concern as to “why the Legislature has remained silent for the past 18 years” since the Texas Supreme Court first connected Texas’s open-courts guarantee to an inherently undiscoverable medical injury in Shah v. Moss, 67 S.W.3d 836 (Tex. 2001).

Among other important business-litigation issues recently addressed by the Texas Supreme Court in Bombadier Aerospace v. SPEP Aircraft Holdings, footnote 17 of the opinion provides a lengthy summary of potential Casteel issues in a jury question about damages – providing a not-so-subtle hint to be aware of potential appeal points in that highly technical area of Texas practice, as they are not reviewable absent objection. No.

Among other important business-litigation issues recently addressed by the Texas Supreme Court in Bombadier Aerospace v. SPEP Aircraft Holdings, footnote 17 of the opinion provides a lengthy summary of potential Casteel issues in a jury question about damages – providing a not-so-subtle hint to be aware of potential appeal points in that highly technical area of Texas practice, as they are not reviewable absent objection. No.  17-0578 (Tex. Nov. 1, 2018) (noting, after describing the applicable principles: “Here, no party raises the issue of charge error, and no party objected to the jury charge on that basis; in fact, the parties explicitly agreed to the form of question four with a single blank for actual damages. Therefore, although we note that question four arguably intermingles compensatory damages for diminution in value with damages for loss of warranty value, damages that Bombardier argues are unsupported, we express no opinion on the validity of question four under our broad-form damages question precedent.” (citations omitted)).

17-0578 (Tex. Nov. 1, 2018) (noting, after describing the applicable principles: “Here, no party raises the issue of charge error, and no party objected to the jury charge on that basis; in fact, the parties explicitly agreed to the form of question four with a single blank for actual damages. Therefore, although we note that question four arguably intermingles compensatory damages for diminution in value with damages for loss of warranty value, damages that Bombardier argues are unsupported, we express no opinion on the validity of question four under our broad-form damages question precedent.” (citations omitted)).

A stealthy Casteel issue was addressed by the Texas Supreme Court in Bombadier Aerospace v. SPEP Aircraft Holdings. The issue arose when the phrase “Plaintiffs” was defined to include several entities – only two of whom actually had a right to recovery damages. The Court found no harm, largely because the parties had reached a stipulation that mitigated potential confusion from the question. The issue is nevertheless worth noting as an aspect of Casteel that has not yet received analysis by the supreme court.

Skyline Commercial v. ISC Acquisition addressed several aspects of the interplay between an express contract and the doctrine of quantum meruit, including:

Skyline Commercial v. ISC Acquisition addressed several aspects of the interplay between an express contract and the doctrine of quantum meruit, including:

- A statement about the scope of a contract, made in response to a motion to transfer venue, did not conclusive resolve the viability of the quantum meruit claim because a party may not judicially admit a question of law;

- The trial court correctly used the applicable Pattern Jury Charge about quantum meruit (reminding, “a trial court should not embellish well-settled pattern jury charges with addendum”); and

- The jury properly weighed conflicting testimony about whether the defendant knew of the relevant orders – and the plaintiff’s expectation of payment for them.

No. 05-17-00028-CV (June 22, 2018) (mem. op.)

The appellant in Bowser v. Craig Ranch Emergency Hospital LLC, a medical negligence case, argued that a Casteel situation arose “because the single [liability] question . . . combined the negligence issue and the proximate cause issue, so it is impossible to assess how the jury was affected by the erroneous proximate cause instruction.” The Fifth Court disagreed: “The Texas Supreme Court has specifically limited its holding in Casteel and its progeny to the submission of broad-form questions incorporating multiple theories of liability or multiple damage elements.” No. 05-16-00639-CV (Jan. 8, 2018) (mem. op.) (citing Bed, Bath & Beyond, Inc. v. Urista, 211 S.W.3d 753, 757 (Tex. 2006)).

The appellant in Bowser v. Craig Ranch Emergency Hospital LLC, a medical negligence case, argued that a Casteel situation arose “because the single [liability] question . . . combined the negligence issue and the proximate cause issue, so it is impossible to assess how the jury was affected by the erroneous proximate cause instruction.” The Fifth Court disagreed: “The Texas Supreme Court has specifically limited its holding in Casteel and its progeny to the submission of broad-form questions incorporating multiple theories of liability or multiple damage elements.” No. 05-16-00639-CV (Jan. 8, 2018) (mem. op.) (citing Bed, Bath & Beyond, Inc. v. Urista, 211 S.W.3d 753, 757 (Tex. 2006)).

A series of oil and gas investments led to a lawsuit between BV Energy Partners and Richard Cheatham, the managing member of their jointly owned company, Tsar Energy II, LLC. Although Cheatham was initially required to work exclusively for Tsar II, that exclusivity provision was eliminated after the company had languished with only one investment made in three years. Cheatham continued to bring oil and gas opportunities to BV, and also made his own acquisitions, but the parties made no further investments were made through Tsar II. Cheatham’s investments proved to be far more lucrative than BV’s, which led BV to sue Cheatham for breach of fiduciary duty. The jury rejected those claims, and the Court of Appeals affirmed. The Court held that there was no charge error in asking the jury to consider whether the parties had formed a partnership to invest in “all” deals (as opposed to “any”) that Cheatham had an opportunity to acquire in the Marcellus Shale. The Court held that was a proper instruction because the justice’s review of the evidence and arguments at trial showed that BV had tried the case on an all-or-nothing theory.

BV Energy Partners, LP v. Cheatham, No. 05-14-00373-CV

Failure To Submit Jury Question on Damages Does Not Waive Sufficiency Arguments on Appeal

July 11, 2013At a trial involving, among other things, counterclaims for breach of contract, the counterclaimant forgot to submit a jury question on the issue of damages. Because the jury agreed with the counterclaimant for all other elements of the breach of contract claim, the counterclaimant moved for judgment and requested that the trial court find that damages for the breach of contract established as a matter of law. The trial court did not expressly rule on the motion for judgment, but instead rendered a take-nothing judgment on the counterclaim.

On appeal, the Court addressed several issues, including whether the counterclaimants had waived any objection to the jury charge on appeal. The Court explained that, under the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure “[w]hen an element of a claim is omitted from the jury charge without objection and no written findings are made by the trial court on that element then the omitted element is deemed to have been found by the court in such a manner as to support the judgment.” Based on this, the Court concluded that the counterclaimants did not waive their claim for damages by failing to submit a jury question on that element of their claim and that they had also not waived argument concerning the legal and factual sufficiency of the trial court’s “deemed finding.”

Jeanette Hooper and her husband Charles sued their lawyers for legal malpractice. The underlying case had been a personal injury suit arising out of a car wreck, which was apparently dismissed after the lawyers sued the owner of the other vehicle instead of the actual driver. The jury awarded $235,000 in damages, based on the testimony of a legal expert who opined that the Hoopers should have recovered $130,000 for past medical expenses, $180,000 for lost earning capacity, $250,000 for pain and suffering, and $250,000 for damages such as loss of consortium and physical impairment. On appeal, however, the court of appeals held that the testimony did not establish a causal link between the underlying car wreck and the subsequent damages. While it was justifiable for the jury to compensate the plaintiffs for damages sustained in the immediate aftermath of the wreck, such as emergency room bills and initial pain and suffering, the “case-within-a-case” aspect of the legal malpractice claim required the plaintiffs to establish a causal connection between the accident and the health problems Charles experienced months and even years after the collision. That connection needed to be made by the testimony of a medical expert, and could not be demonstrated through bare medical records or inferred by the jury. Because some elements of the plaintiffs’ damages were valid and some were invalid, the court of appeals also sustained the defendants’ challenge to the trial court’s submission of a broad-form damages question, reversed the judgment, and remanded for further proceedings.

Kelley & Witherspoon, LLP v. Hooper, No. 05-11-01256-CV

Regency Gas Services owns a natural gas processing facility in the Hugoton Basin. One of the byproducts of natural gas is crude helium. In 1996, Regency entered into a 12-year contract with Keyes Helium Co., which owned a helium processing facility in Oklahoma. Under the agreement, Keyes agreed to purchase all of the crude helium produced by Regency’s facility. But in 2003, Regency found out that one of its biggest customers was unlikely to renew its contracts, which would deprive Regency of the volumes of natural gas needed to make helium production possible. As a result, Regency decided to shut down its plant and move its processing to a nearby facility owned by another company. Keyes sued for breach of contract, contending that Regency had not acted in good faith when it decided to eliminate its production of crude helium. The jury returned a verdict in favor of Regency.

On appeal, Keyes claimed jury charge error in the trial court’s definition of “good faith” under the UCC. Keyes contended that the trial court should have limited its instruction to the one found in the U.C.C., which simply states that good faith means “honesty in fact and the observance of reasonable commercial standards standards in the trade.” The trial court had expanded on that definition by adding the phrase “including whether Regency had a legitimate business reason for eliminating its output under the Contract, as opposed to a desire to avoid the contract.” The court of appeals rejected that argument, concluding that the additional language could not have caused the rendition of an improper verdict because Keyes had failed to submit any evidence that Regency’s decision to shut down its plant had been made in bad faith. The court of appeals also affirmed the trial court’s grant of a directed verdict against Keyes on its claim that the UCC prevented Regency from reducing its output below the estimates stated in the contract, ruling that section 2-306(1) of the UCC did not such reductions if they were made in good faith.

Keyes Helium Co. v. Regency Gas Services, LP, No. 05-10-00929-CV

The members of a limited partnership entered into a partnership agreement providing that they would each relinquish their partnership interest if they departed involuntarily. The agreement also provided that while no payment was required, the remaining partners could still decide to make a payment to the involuntarily departing partner. In late 2008, two of the three partners decided to terminate Arvid Leick. The remaining partners initially offered to pay him in excess of $300,000, but Leick insisted on almost twice that amount. The partnership and the remaining partners then filed suit seeking a declaratory judgment that Leick had been involuntarily terminated and that they therefore did not owe him anything at all. Leick counterclaimed. The jury found that Leick’s termination had been involuntary, but that he still should have been paid what the remaining partners had originally offered. The trial court reduced the award to $125,000, but still entered judgment in favor of Leick.

On appeal, the partnership claimed that the trial court had erred by improperly instructing the jury that the remaining partners had an obligation to treat the involuntarily terminated partner fairly and reasonably. The court of appeals reversed and entered a take-nothing judgment against Leick, holding that this instruction was contrary to the plain language of the partnership agreement, which left it up to the remaining partners whether an involuntarily departure would lead to any payment at all. Although the Texas Revised Partnership Act does require partners to be fair and reasonable to one another, that could not serve as the basis for the jury instruction because Leick was no longer a partner after the day he was terminated. The court of appeals likewise sustained the trial court’s directed verdict against Leick on his claim for breach of fiduciary duty, since that claim also focused on the other partners’ treatment of him after he was terminated, and there was no fiduciary duty for the parties to remain partners with one another. Finally, the court vacated the trial court’s award of attorney fees to Leick, but noted that he still might still be able to recover fees on remand under the Declaratory Judgments Act, even though he was no longer the prevailing party.

LG Insurance Management Services, LP v. Leick, No. 05-10-01646-CV