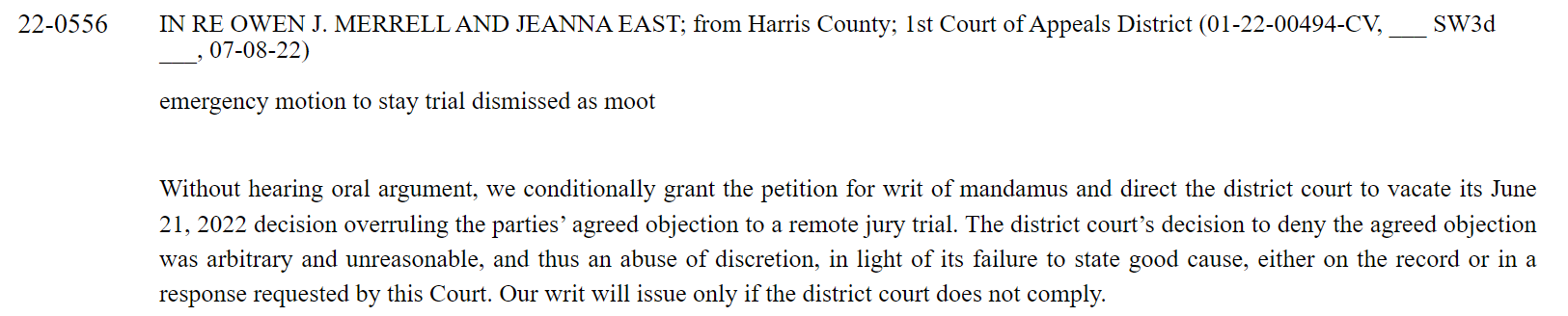

The Fifth Court granted mandamus relief in In re Pillar Income Asset Management, holding that a new-trial order based on “incurable” improper argument was an abuse of discretion because the challenged remarks—though often improper—were not so extreme or inflammatory that an instruction could not cure any harm.

The Fifth Court granted mandamus relief in In re Pillar Income Asset Management, holding that a new-trial order based on “incurable” improper argument was an abuse of discretion because the challenged remarks—though often improper—were not so extreme or inflammatory that an instruction could not cure any harm.

On this record, and under the demanding substantive standard, the Court concluded that personal barbs at opposing counsel, aggressive treatment of an expert, references outside the record, statements of personal opinion, and brief appeals to local or religious identity were improper but curable, and therefore could not support a new trial without timely objections and requested curative instructions.

Distinguishing the Fifth Circuit’s recent Clapper decision that reversed because of improper argument, the Court underscored that Texas requires proof that the challenged rhetoric was “so extreme that a juror of ordinary intelligence could have been persuaded by that argument to agree to a verdict contrary to that to which he would have agreed but for such argument.” The Court summarized: “Incurable argument is rare.” 05-25-00205-CV; Jan. 14, 2026.