The parties’ dispute in Sazy v. J.R. Birdwell Constr. & Restoration, LLC went to trial and final judgment on the jury’s verdict. The sole issue on appeal was the denial of the defendant’s motion to transfer venue pretrial. While pretrial review of venue decisions is significantly limited by statute, those decisions are fair game for appeal post-trial. No. 05-19-01351-CV (April 1, 2021) (mem. op.).

Author Archives: David Coale

The state Senate has undertaken the redistricting the current 14 intermediate-court districts in Texas; Law360 has a thorough story and related chart after a recent Jurisprudence Committee hearing. As for Dallas, the Senate’s plan links Austin and Dallas (right, below), cities that have been jurisprudentially distinct since at least 1893 (left, below). Please make your opinions known on the “I-35 Court of Appeals” as the Legislature continues to consider this proposal.

Many books and movies involve tales of scary creatures who return, ranging from Grendel’s family in the ancient epic of Beowulf to “Where’s My Mummy?”, an underappreciated part of the Scooby Doo multiverse. The to pic of briefing waiver returns in the majority opinion from Herczeg v. City of Dallas, which found waiver in a sovereign-immunity case because the opening brief did not address untimeliness or exhaustion of remedies. It distinguished St. John Missionary Baptist v. Flakes, 595 S.W.3d 211 (Tex. 2020), as involving “two grounds [that] were not actually independent but were inextricably intertwined,” while here, “untimeliness and failure to exhaust administrative remedies are independent of the City’s other grounds, which focused on the merits of Herczeg’s claims.” A dissent questioned whether the older authority cited by the majority continued to be viable after Flakes. Justice Garcia wrote for the majority, joined by Justice Smith; Justice Schenck dissented. No. 05-19-01023-CV (March 29, 2021) (mem. op.).

pic of briefing waiver returns in the majority opinion from Herczeg v. City of Dallas, which found waiver in a sovereign-immunity case because the opening brief did not address untimeliness or exhaustion of remedies. It distinguished St. John Missionary Baptist v. Flakes, 595 S.W.3d 211 (Tex. 2020), as involving “two grounds [that] were not actually independent but were inextricably intertwined,” while here, “untimeliness and failure to exhaust administrative remedies are independent of the City’s other grounds, which focused on the merits of Herczeg’s claims.” A dissent questioned whether the older authority cited by the majority continued to be viable after Flakes. Justice Garcia wrote for the majority, joined by Justice Smith; Justice Schenck dissented. No. 05-19-01023-CV (March 29, 2021) (mem. op.).

A common sci-fi movie trope is the image of a “mad scientist” working in the laboratory. Texas appellate lawyers and judges have a similar look when applying Crown Life Ins. Co. v. Casteel, 22 S.W.3d 378 (2000), which deals with the vexing problem of jury charges that mix valid and invalid elements. The Fifth Court’s majority opinion in Kansas City Southern Ry. Co. v. Horton, No. 05-19-00856-CV (March 11, 2021) (mem. op.), after finding one of the plaintiffs’ two liability theories preempted by federal law, found a Casteel issue with a broad-form negligence submission in a personal injury case. It distinguished an earlier Dallas case and a Corpus Christi decision as involving factual-sufficiency rather than legal-validity issues. A dissent took issue with the holding about preemption.

A common sci-fi movie trope is the image of a “mad scientist” working in the laboratory. Texas appellate lawyers and judges have a similar look when applying Crown Life Ins. Co. v. Casteel, 22 S.W.3d 378 (2000), which deals with the vexing problem of jury charges that mix valid and invalid elements. The Fifth Court’s majority opinion in Kansas City Southern Ry. Co. v. Horton, No. 05-19-00856-CV (March 11, 2021) (mem. op.), after finding one of the plaintiffs’ two liability theories preempted by federal law, found a Casteel issue with a broad-form negligence submission in a personal injury case. It distinguished an earlier Dallas case and a Corpus Christi decision as involving factual-sufficiency rather than legal-validity issues. A dissent took issue with the holding about preemption.

“’When a trial court’s order does not specify the grounds for its summary judgment, an appellate court must affirm the summary judgment if any of the theories presented to the trial court and preserved for appellate review are meritorious.’ However, when the trial court’s summary judgment order does

“’When a trial court’s order does not specify the grounds for its summary judgment, an appellate court must affirm the summary judgment if any of the theories presented to the trial court and preserved for appellate review are meritorious.’ However, when the trial court’s summary judgment order does

specify a ground on which it was granted, we generally limit our review to that ground.

Here, because the trial court’s summary judgment order specified the ground

on which it was granted—that Finley was a released party because the term

‘predecessor’ in the Release includes an entity that was a ‘predecessor in title’ to

the subject property interest—we will limit our review to that theory.” Headington Royalty v. Finley Resources, No. 05-19-00291-CV (March 18, 2021) (citations omitted) (emphasis added).

This is a cross-post from 600Camp, which follows commercial litigation in the Fifth Circuit.

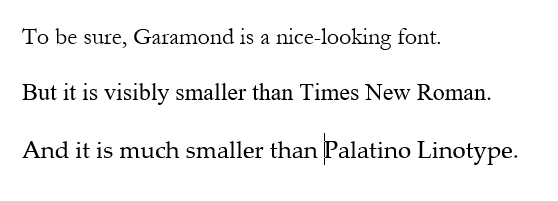

The DC Circuit’s recent style manual amendment that criticized the use of “Garamond” font has drawn national attention. As this matter has now become a pressing issue facing the federal courts, 600Camp weighs in with these thoughts, all of which are written in 14-point size:

Accordingly, if you really like Garamond and are writing a brief with a word limit rather than a page limit, you should consider bumping the size up to 15-point. And of course, in a jurisdiction with page limits rather than word limits, Garamond offers a way to add more substance to your submission–but be careful that this extra substance does not come at the price of less visibility.

The Fifth Court rejected an argument that a supreme court emergency order extended the trial court’s plenary power after a case’s dismissal: “[T]he language in the emergency orders ‘giving a court the power to modify or suspend “deadlines and procedures” presupposes a pre-existing power or authority over the case or the proceedings. . . . It does not suggest that a court can create jurisdiction for itself where the jurisdiction would otherwise be absent[.]’ Here, the trial court lost jurisdiction over the case on July 20, and the motion to reinstate was not filed until November. Because the trial court lacked jurisdiction over the case by the time the motion to reinstate was filed, it could not avail itself of the emergency order to reinstate the case, and the challenged orders are void.” Quariab v. Khalili, No. 05-20-00979-CV (March 15, 2021) (mem. op.) (citing In re State ex rel. Ogg, No. WR-91,936-01, 2021 WL 800761, at *3 (Tex. Crim. App. Mar. 3, 2021)).

“Texas law provides district court judges with ‘the power to

“Texas law provides district court judges with ‘the power to

issue writs necessary to enforce their jurisdiction.’ While the Taxing Entities urge the Post Judgment Order falls within this power to ‘enforce’ the judgment, they fail to explain how an order withdrawing part of the relief afforded by the judgment would amount to ‘enforcement’ or be available to a party after expiration of the trial court’s plenary power other than by appeal.” NMF Partnership v. City of Dallas NMF Partnership v. City of Dallas, No. 05-19-01578-CV (March 17, 2021) (mem. op.) (citations omitted).

The issue: “[W]hether the word ‘predecessors’ in the Release’s phrase “[Headington] waives, releases, acquits and discharges Petro Canyon and its affiliates and their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees, agents, predecessors and representatives for any liabilities, claims, . . . [and] causes of action . . . related in any way to the Loving County Tract” refers to (i) Petro Canyon and its affiliates’ corporate entities and agents (‘Players’) or (ii) prior parties in Petro Canyon’s chain of title (‘Spectators’) that are otherwise unrelated to Petro Canyon.”

The issue: “[W]hether the word ‘predecessors’ in the Release’s phrase “[Headington] waives, releases, acquits and discharges Petro Canyon and its affiliates and their respective officers, directors, shareholders, employees, agents, predecessors and representatives for any liabilities, claims, . . . [and] causes of action . . . related in any way to the Loving County Tract” refers to (i) Petro Canyon and its affiliates’ corporate entities and agents (‘Players’) or (ii) prior parties in Petro Canyon’s chain of title (‘Spectators’) that are otherwise unrelated to Petro Canyon.”

Held: “‘[P]redecessors’ is in a string of entity-related groups (‘Players’), not chain of title-related owners of the real property interest (‘Spectators’). Excluding ‘predecessor,’

each of those other terms in the Release relate as ‘birds of a feather’ to the corporate

composition or structure of Petro Canyon and its affiliates. The placement of the

term ‘predecessors’ along with its ordinary meaning gives the term a certain legal

meaning.”

Dissent: “The majority’s interpretation of the term “predecessors” in the Release fails to acknowledge the context of the circumstances surrounding the PCH Agreement, including the events leading to its formation, the relationships of the parties, each party’s motivations for entering the agreement, and the intentions of the parties as expressed in the agreement. The majority’s interpretation of the Release also impermissibly adds language to the Release, and the majority opinion conflicts with this Court’s prior opinions.” Headington Royalty v. Finley Resources, No. 05-19-00291-CV (March 18, 2021).

My colleague Michael Hurst wrote an insightful op-ed in the Dallas Morning News about a proposed system of specialized business courts for Texas. He questions whether it fits well with constitutional guaranties of the right to jury trial.

My colleague Michael Hurst wrote an insightful op-ed in the Dallas Morning News about a proposed system of specialized business courts for Texas. He questions whether it fits well with constitutional guaranties of the right to jury trial.

In Anubis Pictures LLC v. Selig, a dispute about the development of a screenplay, two terms from an early-stage NDA were key to resolving it:

In Anubis Pictures LLC v. Selig, a dispute about the development of a screenplay, two terms from an early-stage NDA were key to resolving it:

As to the parties’ relationship: “Neither party is bound to proceed with any transaction between the parties unless and until both parties sign a formal, written agreement setting forth the terms of such transaction. At any time prior to the completion of such a formal, written agreement, either party may terminate the Discussions and refuse to enter into any subsequent transaction, for any reason or for no reason, without liability for such termination, even if the other performed work or incurred expenses related to a potential transaction in anticipation that the parties would enter into a formal, written agreement regarding such transaction.”

As to the documents shared: “To be covered under the terms of the NDA, confidential information disclosed in written form was required to be marked confidential on its face. Any oral statement intended to be confidential had to be clearly designated as such by the disclosing party.” No. 05-19-00817-CV (March 3, 2021) (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court denied mandamus relief in a dispute about third-party document confidentiality, observing that the party resisting discovery (1) “relied, in part, on a non-disclosure agreement that by its very terms expired years before the documents were subpoenaed and produced.” and (2) “relied on the affidavit of the President of one of [the movant’s] portfolio companies, which contains conclusory allegations concerning the confidential nature of [its] business and strategies, and of potential harm. Those assertions, in and of themselves, are not dispositive of the objection to confidentiality.” In re Edelman, No. 05-21-00085-CV (March 5, 2021).

The Fifth Court denied mandamus relief in a dispute about third-party document confidentiality, observing that the party resisting discovery (1) “relied, in part, on a non-disclosure agreement that by its very terms expired years before the documents were subpoenaed and produced.” and (2) “relied on the affidavit of the President of one of [the movant’s] portfolio companies, which contains conclusory allegations concerning the confidential nature of [its] business and strategies, and of potential harm. Those assertions, in and of themselves, are not dispositive of the objection to confidentiality.” In re Edelman, No. 05-21-00085-CV (March 5, 2021).

A dissent concluded that one of the documents was protected by Texas’s shield statute, observing: “[The interest implicated by Exhibit M is not merely proprietary but also appears to concern a recurring relationship between a media relations firm and a news reporter, the disclosure of which would directly implicate the journalist’s news gathering rights.”

A group of investors (“FPH”) in a business (“FSG”) sought the appointment of a receiver to review and report on the finances of FSG. The trial court (1) agreed, and then (2) allowed FSG to supersede the order with a $10,000 bond while it took an interlocutory appeal, but then (3) allowed FPH to post a “counter-supersedeas bond” of $11,875 so that the receiver’s work could proceed during the interlocutory appeal. The Fifth Court found that “[TRAP] 24.2(a)(3) expressly permitted the trial court to allow FPH to post a counter-supersedeas bond,” and then found the bond amount to be appropriate in light of “[t]he fact that FSG continues to have sole control of its management” and the evidence presented about FSG’s financial situation. Five Star Global, LLC v. Hulme, No. 05-20-00940-CV (March 2, 2021).

A group of investors (“FPH”) in a business (“FSG”) sought the appointment of a receiver to review and report on the finances of FSG. The trial court (1) agreed, and then (2) allowed FSG to supersede the order with a $10,000 bond while it took an interlocutory appeal, but then (3) allowed FPH to post a “counter-supersedeas bond” of $11,875 so that the receiver’s work could proceed during the interlocutory appeal. The Fifth Court found that “[TRAP] 24.2(a)(3) expressly permitted the trial court to allow FPH to post a counter-supersedeas bond,” and then found the bond amount to be appropriate in light of “[t]he fact that FSG continues to have sole control of its management” and the evidence presented about FSG’s financial situation. Five Star Global, LLC v. Hulme, No. 05-20-00940-CV (March 2, 2021).

Gharavi owned a business that won an arbitration against Khademazad. Gharavi sued to enforce the award, and along the way, made a comment about Khademazad and the award on Yelp. The parties resolved their differences and entered a settlement agreement of the lawsuit about the award, in which Khademazad released all claims “directly or indirectly attributable to the transaction or occurences made the basis of this lawsuit.” Several weeks later, Khademazad sued for libel and similar claims based on the Yelp post. The Fifth Court found that this suit was barred by the release: “Without question, the Yelp review was, if not directly, then indirectly attributable to Khademazad’s failure to pay for Aidris’s services and the lawsuit that followed. Khademazad’s claims here are clearly within the subject matter of the release.” Gharavi v. Khademazad, No. 05-20-00083-CV (Feb. 2, 2021) (mem. op.).

The parties in Ninety Nine Physician Services, PLLC v. Murray arbitrate d a business dispute; the lingering issue at confirmation was an award of $341,680 in attorneys’ fees. The Fifth Court found that the award was proper, reasoning as follows:

d a business dispute; the lingering issue at confirmation was an award of $341,680 in attorneys’ fees. The Fifth Court found that the award was proper, reasoning as follows:

- “[U]nder the parties’ distinct agreement and incorporation of the AAA rules, there were three circumstances in which the arbitrator was vested with the authority to award attorney’s fees (1) if all parties requested such an award or (2) if it was separately authorized by law or (3) if it is authorized by the arbitration agreement.” (emphasis in original); and then

- “Both parties submitted posthearing briefs in which they requested attorney’s fees. In their briefing, Appellees urged, as they do here, there was no basis in the general law to award fees to Appellant. … Appellees contend Appellant’s post-hearing brief is not a proper request for attorney’s fees. The arbitrator in interpreting the Commercial Rules evidently disagreed with Appellees and found the post-hearing briefs to be requests for attorney’s fees under Rule 47(d)(ii).”

The Court thus reversed a trial-court ruling that vacated that portion of the award. A concurrence would have reached the same result for a different reason: “Because appellant did not file any pleading affirmatively seeking attorneys’ fees until after the arbitration hearing, the arbitrator abused his discretion in awarding attorneys’ fees to appellant. The arbitrator’s mistake of law, however, is not grounds to vacate the award, and the trial court erred in doing so. Consequently, appellant was entitled to enforcement of the attorneys’ fees award but not on the basis relied upon by the majority.” No. 05-19-01216-CV (Feb. 22, 2021) (mem. op.).

The Texas Supreme Court heard arguments today in In re: Estate of Johnson, No. 05-18-01193-CV (Nov. 4, 2019) (mem. op.), which presents a fundamental issue in Texas probate law–whether a beneficiary’s acceptance of benefits under a will defeats that beneficiary’s standing to challenge that will.

If you have power and a little time for a half-hour of ethics CLE, the State Bar Litigation Section has put together this good video about the proposed new disciplinary rules. The voting period ends March 4 and you can do that on the State Bar website.

If you have power and a little time for a half-hour of ethics CLE, the State Bar Litigation Section has put together this good video about the proposed new disciplinary rules. The voting period ends March 4 and you can do that on the State Bar website.

Allegations about a great deal of activity that does not implicate the TCPA,’s protection of the right of association, do not implicate the TCPA’s protection of the right of association: “Tiffany first contends that Rupert’s allegations of conspiracy and joint enterprise meet this standard because they involve the disposition of Marie’s estate (including certain community property) and ‘two decades of publicly filed lawsuits.’ She cites no authority for the proposition that the estate proceedings of a private individual involve public or citizen’s participation, and we have found no such authority. Likewise, we find no authority supporting the notion that extended litigation between and among these parties becomes a matter of public or citizen’s participation merely because of its volume or allegedly repetitive nature. On the contrary, the allegations made by Rupert are of an intensely personal nature, and they address actions involving the personal relationships within the Pollard family.” Pollard v. Pollard, No. 05-19-00240-CV (Feb. 8, 2021) (mem. op.).

Allegations about a great deal of activity that does not implicate the TCPA,’s protection of the right of association, do not implicate the TCPA’s protection of the right of association: “Tiffany first contends that Rupert’s allegations of conspiracy and joint enterprise meet this standard because they involve the disposition of Marie’s estate (including certain community property) and ‘two decades of publicly filed lawsuits.’ She cites no authority for the proposition that the estate proceedings of a private individual involve public or citizen’s participation, and we have found no such authority. Likewise, we find no authority supporting the notion that extended litigation between and among these parties becomes a matter of public or citizen’s participation merely because of its volume or allegedly repetitive nature. On the contrary, the allegations made by Rupert are of an intensely personal nature, and they address actions involving the personal relationships within the Pollard family.” Pollard v. Pollard, No. 05-19-00240-CV (Feb. 8, 2021) (mem. op.).

In a premises-liability case, the defendant challenged the expert testimony relied upon by the plaintiff. The Fifth Court rejected the challenge, reasoning: “Essentially, United contends that because English’s opinions have been excluded by other courts, we should “follow the lead” of these other courts and not consider them. We reject United’s invitation. United has not cited to any specific conclusory statements in English’s report. Rather, United argues that English’s report is conclusory because he provided a ‘cut-and-paste job’ that is a ‘rather generic’ opinion that ‘he regurgitates every time he

In a premises-liability case, the defendant challenged the expert testimony relied upon by the plaintiff. The Fifth Court rejected the challenge, reasoning: “Essentially, United contends that because English’s opinions have been excluded by other courts, we should “follow the lead” of these other courts and not consider them. We reject United’s invitation. United has not cited to any specific conclusory statements in English’s report. Rather, United argues that English’s report is conclusory because he provided a ‘cut-and-paste job’ that is a ‘rather generic’ opinion that ‘he regurgitates every time he

is hired.’ However, such statements provide no particular basis for United’s

objection. Objections that statements are conclusory may not be conclusory

themselves.” McIntyre v. United Supermarkets, No. 05-19-01252-CV (Feb. 4, 2021) (mem. op.).

Sherie McIntyre was injured when she fell in a pothole in a grocery store parking lot. The Fifth Court (in Justice Craig Smith‘s first appearance in this blog) reversed a defense summary judgment in McIntyre v. United Supermarkets, finding a fact issue on the question of the store owner’s constructive knowledge of the pothole: “Trevino testified that he inspected the parking lot approximately twenty to twenty-four times during the first six months of the store’s opening. He noticed the spot where McIntyre fell but ‘didn’t feel that it needed to be repaired . . . It never stood out as a haza

Sherie McIntyre was injured when she fell in a pothole in a grocery store parking lot. The Fifth Court (in Justice Craig Smith‘s first appearance in this blog) reversed a defense summary judgment in McIntyre v. United Supermarkets, finding a fact issue on the question of the store owner’s constructive knowledge of the pothole: “Trevino testified that he inspected the parking lot approximately twenty to twenty-four times during the first six months of the store’s opening. He noticed the spot where McIntyre fell but ‘didn’t feel that it needed to be repaired . . . It never stood out as a haza rd.’ Thus, Trevino’s repeated inspections put him in close proximity to observe the pothole, which he in fact did notice. Trevino acknowledged that the parking lot was restriped before United opened the new store and had not been restriped since then. A picture of the pothole shows the white stripe going over part of the pothole indicating it had been present for at least six months. Thus, McIntyre produced more than a scintilla of evidence to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to whether United had constructive notice of the pothole.” No. 05-19-01252-CV (Feb. 4, 2021) (mem. op.). The Court also found a fact issue on the question of unreasonable danger.

rd.’ Thus, Trevino’s repeated inspections put him in close proximity to observe the pothole, which he in fact did notice. Trevino acknowledged that the parking lot was restriped before United opened the new store and had not been restriped since then. A picture of the pothole shows the white stripe going over part of the pothole indicating it had been present for at least six months. Thus, McIntyre produced more than a scintilla of evidence to raise a genuine issue of material fact as to whether United had constructive notice of the pothole.” No. 05-19-01252-CV (Feb. 4, 2021) (mem. op.). The Court also found a fact issue on the question of unreasonable danger.

Toyota Motor Sales v. Reavis, a companion case to a still-ongoing appeal of a major products-liability judgment, affirmed the denial of Toyota’s motion to seal certain trial exhibits. After reviewing Toyota’s case for confidentiality, the Fifth Court then turned to available less-restrictive means, holding: “Beyond Toyota’s blanket assertions that a total seal is necessary and redaction would be meaningless, Toyota did not offer any additional testimony or evidence regarding whether the Toyota documents could be redacted or otherwise altered while still protecting its interest. Toyota also contends on appeal that it showed sealing was the least restrictive means to protect its interest here because it sought to seal ‘just four exhibits from a trial involving over 900 exhibits and [covering] pages of closed-courtroom testimony from more than 3,200 pages of trial

Toyota Motor Sales v. Reavis, a companion case to a still-ongoing appeal of a major products-liability judgment, affirmed the denial of Toyota’s motion to seal certain trial exhibits. After reviewing Toyota’s case for confidentiality, the Fifth Court then turned to available less-restrictive means, holding: “Beyond Toyota’s blanket assertions that a total seal is necessary and redaction would be meaningless, Toyota did not offer any additional testimony or evidence regarding whether the Toyota documents could be redacted or otherwise altered while still protecting its interest. Toyota also contends on appeal that it showed sealing was the least restrictive means to protect its interest here because it sought to seal ‘just four exhibits from a trial involving over 900 exhibits and [covering] pages of closed-courtroom testimony from more than 3,200 pages of trial

transcripts.’ This argument misses the point. Rule 76a imposes strict requirements to obtain a sealing order, and parties are not rewarded with a sealing order simply because they ask the court to only seal a few exhibits or a small amount of testimony. No matter how many exhibits a party seeks to seal, that party must still meet the

requirements of the rule.” No. 05-19-00284-CV (Feb. 4, 2021) (mem. op.).

Toyota Motor Sales v. Reavis, a companion case to a still-ongoing appeal of a major products-liability judgment, affirmed the denial of Toyota’s motion to seal certain trial exhibits. Noting the general presumption in favor of open records, the Fifth Court observed, inter alia:

Toyota Motor Sales v. Reavis, a companion case to a still-ongoing appeal of a major products-liability judgment, affirmed the denial of Toyota’s motion to seal certain trial exhibits. Noting the general presumption in favor of open records, the Fifth Court observed, inter alia:

- “[E]ven assuming the court records contain trade secrets, the existence of trade secrets standing alone is insufficient to overcome the presumption of openness and allow the records to be permanently sealed.”

- “Because Toyota did not take adequate steps during trial to protect the exhibits and related testimony from public disclosure and did not seek an instruction prohibiting the jury and other non-parties from discussing the documents beyond the setting of the trial, we conclude any interest Toyota had in maintaining secrecy of the records does not “clearly outweigh” the presumption of openness.”

No. 05-19-00284-CV (Feb. 4, 2021) (mem. op.).

A vote is underway – eight new Texas Disciplinary Rules have been proposed, and the supreme court has authorized a State Bar membership vote about them. This page has information about the proposed rules.

A vote is underway – eight new Texas Disciplinary Rules have been proposed, and the supreme court has authorized a State Bar membership vote about them. This page has information about the proposed rules.

Singh v. Gill reminds of the importance of strict compliance with Tex. R. Civ. P. 106, the substituted-service rule:

Singh v. Gill reminds of the importance of strict compliance with Tex. R. Civ. P. 106, the substituted-service rule:

- Location. “Gill’s affidavit stated only that Gill did not know where Singh could be found. Her attorney’s affidavit recounted e-mail and telephone conversations with Singh in which he refused to provide his location. Neither affidavit, however, stated facts showing that service under rule 106(a) had been attempted. … “

- Attempts. “Moreover, the affidavits do not exhibit the diligence necessary to support substituted service. ‘A diligent search must include inquiries that someone who really wants to find the defendant would make, and diligence is measured not by the quantity of the search but by its quality.’ Here, there is no indication that Gill’s diligence included searching public data or ‘obvious inquiries’ a prudent investigator would have made,’ such as attempting service by mail to obtain a forwarding address or locating and contacting other persons who would likely have information about Singh, beyond Singh’s immediate family in India.”

No. 05-19-01146-CV (Jan. 20, 2021) (mem. op.).

This is a crosspost from 600Hemphill, which follows business litigation in the Texas Supreme Court; the court of appeals opinion under review came from the Fifth Court.

_______

A per curiam opinion, based on the Court’s recent opinion in Federal Home Loan Mortgage Co. v. Zepeda, 601 S.W.3d 763 (Tex. 2020), reminded about a lender’s equitable-subordination rights:

A per curiam opinion, based on the Court’s recent opinion in Federal Home Loan Mortgage Co. v. Zepeda, 601 S.W.3d 763 (Tex. 2020), reminded about a lender’s equitable-subordination rights:

“[E]quitable-subrogation rights become fixed at the time the proceeds from a later loan are used to discharge an earlier lien. A lender’s negligence in preserving its rights under its own lien thus does not deprive the lender of its rights in equity to assert an earlier lien that was discharged using proceeds from the later loan. Although we considered the lender’s negligence in Sims, that analysis is limited to the lien-priority context.

Applying Zepeda to this case, the court of appeals erred in concluding that PNC’s  failure to timely foreclose under the deed of trust bars its subrogation rights. The availability of better credit terms and interest rates can make refinancing an attractive financial tool for borrowers. Subrogation operates as a hedge against the risk of refinancing the outstanding amount of an existing loan, opening this credit market to borrowers. Subrogation permits a lender to assert rights under a lien its loan has satisfied when the lender’s own lien is infirm.” PNC Mortgage v. Howard, No. No. 19-0842 (Jan. 29, 2021).

failure to timely foreclose under the deed of trust bars its subrogation rights. The availability of better credit terms and interest rates can make refinancing an attractive financial tool for borrowers. Subrogation operates as a hedge against the risk of refinancing the outstanding amount of an existing loan, opening this credit market to borrowers. Subrogation permits a lender to assert rights under a lien its loan has satisfied when the lender’s own lien is infirm.” PNC Mortgage v. Howard, No. No. 19-0842 (Jan. 29, 2021).

A construction company sued for nonpayment; on the eve of trial, the defendants objected to the admission of damages evidence because an earlier request for disclosure, served with the answer, had not been answered. The Fifth Court affirmed the trial court’s decision to exclude, noting a lack of evidence either as to good cause or a lack or prejudice (it is not clear from the opinion what other discovery may have been done: “Construction offered no evidence to demonstrate the absence of unfair surprise or prejudice. Indeed, there is nothing to suggest that Defendants had enough evidence to reasonably assess settlement, avoid trial by ambush, or prepare rebuttal to expert testimony.” (citation omitted). F 1 Construction v. Banz, No. 05-19-00717-CV (Jan. 20, 2021) (mem. op.)

A construction company sued for nonpayment; on the eve of trial, the defendants objected to the admission of damages evidence because an earlier request for disclosure, served with the answer, had not been answered. The Fifth Court affirmed the trial court’s decision to exclude, noting a lack of evidence either as to good cause or a lack or prejudice (it is not clear from the opinion what other discovery may have been done: “Construction offered no evidence to demonstrate the absence of unfair surprise or prejudice. Indeed, there is nothing to suggest that Defendants had enough evidence to reasonably assess settlement, avoid trial by ambush, or prepare rebuttal to expert testimony.” (citation omitted). F 1 Construction v. Banz, No. 05-19-00717-CV (Jan. 20, 2021) (mem. op.)

A late discovery supplementation may be allowed if the party shows good cause and a lack of unfair surprise. The Fifth Court reversed a trial court ruling about an expert supplementation when, inter alia: “The record shows (1) Mr. Longeway’s report was based almost entirely on his inspection of the job site’s deactivated electrical lines and (2) the lines’ deactivation could be performed only by the electric delivery company and was not completed until November 30, 2018. Appellants received Mr. Longeway’s report on January 11, 2019, and filed their motion for reconsideration and new trial, with that report attached, several days later. Weekley’s response to the attempted late designation focused only on [another expert’s] report and did not specifically address good cause or unfair surprise or prejudice as to Mr. Longeway.” Paniagua v. Weekley Homes, No. 05-19-00439-CV (Jan. 13, 2021).

A late discovery supplementation may be allowed if the party shows good cause and a lack of unfair surprise. The Fifth Court reversed a trial court ruling about an expert supplementation when, inter alia: “The record shows (1) Mr. Longeway’s report was based almost entirely on his inspection of the job site’s deactivated electrical lines and (2) the lines’ deactivation could be performed only by the electric delivery company and was not completed until November 30, 2018. Appellants received Mr. Longeway’s report on January 11, 2019, and filed their motion for reconsideration and new trial, with that report attached, several days later. Weekley’s response to the attempted late designation focused only on [another expert’s] report and did not specifically address good cause or unfair surprise or prejudice as to Mr. Longeway.” Paniagua v. Weekley Homes, No. 05-19-00439-CV (Jan. 13, 2021).

Thi s is a crosspost from 600Hemphill, which reviews business cases in the Texas Supreme Court. This case originated from the Fifth Court.

s is a crosspost from 600Hemphill, which reviews business cases in the Texas Supreme Court. This case originated from the Fifth Court.

In a per curiam opinion issued without argument, the Texas Supreme Court reminded that it really meant its holding in Pike v. Texas EMC Management LLC, about the distinction between standing and capacity, as applied to the question whether a particular injury is suffered by the named plaintiff or the relevant business entity. Cooke v. Karlseng, No. 19-0829 (Jan. 22, 2021).

This is a cross post from 600Hemphill, which follows business cases in the Texas Supreme Court:

On January 15, the Texas Supreme Court granted an emergency stay in In re: Enven Energy Corp., No. 21-0030, as to the denial of a continuance motion involving COVID-19 issues. The parties’ briefs can be reviewed here, and the merits of the mandamus petition remain pending before the Court.

The Fifth Court concluded that a fact issue was raised on the issue of a contractor’s actual exercise of control based on this evidence: “Leobardo Maravilla’s testimony that Mr. Holmes ‘will always demand to me to work a certain way,’ ‘didn’t allow me to freely do what I know how to work,’ required him to purchase new scaffolding, took him to the building supply store, directed him to buy the aluminum scaffolding his employees were using on the day of the accident, and told him to stay at the project site and continue working even though Mr. Holmes left due to weather conditions,” bolstered by an expert report stating that “while Leobardo Maravilla’s crew continued their work in the ongoing ‘thunderstorm,’ there were numerous lightning strikes in the area that likely energized the rebar in the wet concrete on which they were standing while holding onto the metal scaffolding, thus causing their injuries.” Paniagua v. Weekley Homes, No. 05-19-00439-CV (Jan. 13, 2021) (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court concluded that a fact issue was raised on the issue of a contractor’s actual exercise of control based on this evidence: “Leobardo Maravilla’s testimony that Mr. Holmes ‘will always demand to me to work a certain way,’ ‘didn’t allow me to freely do what I know how to work,’ required him to purchase new scaffolding, took him to the building supply store, directed him to buy the aluminum scaffolding his employees were using on the day of the accident, and told him to stay at the project site and continue working even though Mr. Holmes left due to weather conditions,” bolstered by an expert report stating that “while Leobardo Maravilla’s crew continued their work in the ongoing ‘thunderstorm,’ there were numerous lightning strikes in the area that likely energized the rebar in the wet concrete on which they were standing while holding onto the metal scaffolding, thus causing their injuries.” Paniagua v. Weekley Homes, No. 05-19-00439-CV (Jan. 13, 2021) (mem. op.).

Equitable doctrines such as unjust enrichment, unclean hands, and quasi-estoppel are frequently cited, but by their nature, they are difficult to define with specificity. An uncommon “data point” about unjust enrichment appeared in Hawkins v. Jenkins, No. 05-19-01396-CV (Jan. 8, 2021) (mem. op.) The trial court awarded roughly $10,000 in connection with certain home improvements; the Fifth Court affirmed, noting that “the record contains evidence that appellant reaped a financial benefit from the improvements: she sold the house for $77,000 above its value before appellees made the improvements.”

The majority opinion in Return Lee to Lee Park v. Rawlings, No. 05-19-00456-CV (Dec. 28, 2020), which affirmed a judgment that allowed the removal of two high-profile Confederate memorials from City of Dallas land, summarized the current state of appellate-waiver law after recent Texas Supreme Court opinions:

“Appellate briefs ‘are meant to acquaint the court with the issues in a case and to present argument that will enable the court to decide the case.’ Tex. R. App. P 38.9. Briefs are to be liberally, but reasonably, construed so that the right to appeal is not lost by waiver. Horron v. Stovall, 591 S.W.3d 567, 569 (Tex. 2019) (per curiam). Appellate courts have the authority to request additional briefing on an unbriefed issue that was fairly included in or inextricably entwined with a briefed issue. St. John Missionary Baptist v. Flakes, 595 S.W.3d 211, 216 (Tex. 2020) (per curiam). However, appellate courts retain authority and discretion to deem an unbriefed point waived in lieu of requesting additional briefing. Horton, 519 S.W.3d at 569–70. Whether that discretion has been properly exercised depends on the facts of the case. Id.”

The question in State of Texas v. Mesquite Creek Devel., Inc.. was whether the trial court erred in dismissing a condemnation case based on the state’s failure to timely disclose an appraisal. The Fifth Court observed: “The supreme court utilizes four principles to determine whether the legislature clearly intended a statute to set jurisdictional requirements: “(1) the plain meaning of the statute, (2) whether the statute contains specific consequences for noncompliance, (3) the purpose of the statute, and (4) the consequences that would result from each construction.” Applying those factors, the Court found that this issue was not jurisdictional. No. 05-19-00028-CV (Dec. 31, 2020).

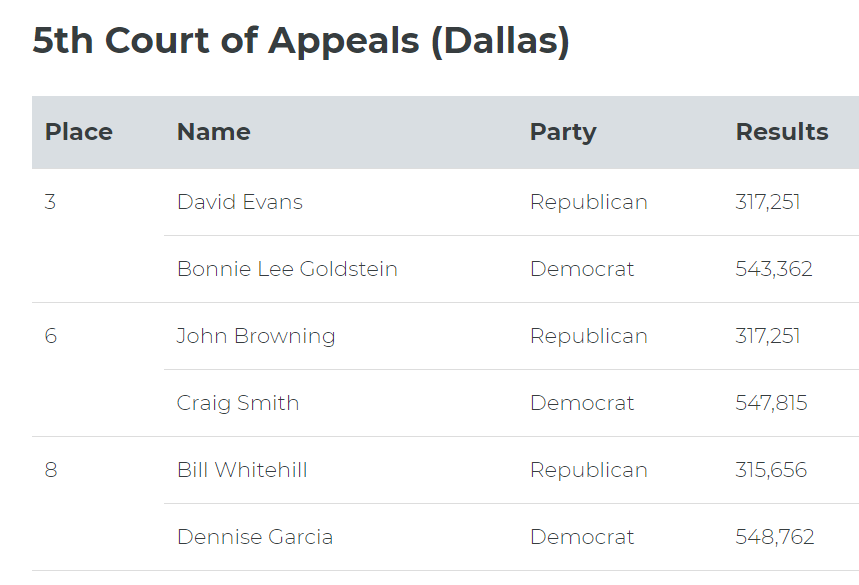

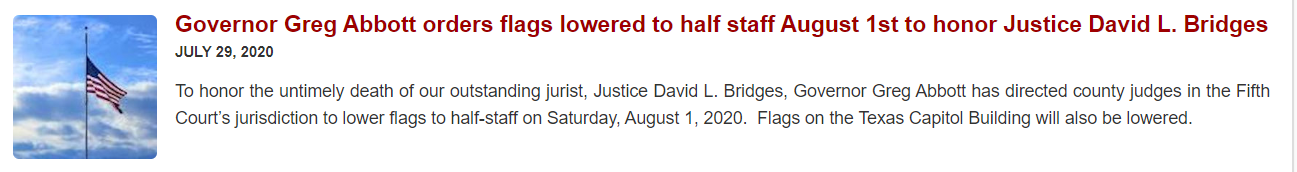

Three new Justices join the Fifth Court at the start of 2021 –

Three new Justices join the Fifth Court at the start of 2021 –

- Hon. Bonnie Lee Goldstein, who joins the Court after service since 2014 on the 44th District Court of Dallas County;

- Hon. Craig Smith, who served since 2006 on the 192nd District Court of Dallas County; and

- Hon. Dennise Garcia, who has presided over the 303rd District Court of Dallas County since 2004.

The 44th and 192nd are civil district courts and the 303rd is a family district court. When the pandemic subsides, none of the new Justices will have to change their commutes, as all three of these courts are located in the George Allen courthouse.

A temporary-injunction order about confidentiality obligations failed for lack of specificity in Wimbrey v. WorldVentures: “Paragraph 3 merely includes a list of items that the court found the covenants were intended to protect. By failing to define, explain, or otherwise describe what constitutes WorldVentures’s ‘confidential information,’ the order leaves appellants to speculate about what particular information or item would constitute ‘confidential information’ and thus fails to provide necessary notice as to how to conform their conduct.” The Court contrasted the order in McCaskill v. National Circuit Assembly, No. 05-17-01289-CV, 2018 WL 3154616, at *3 (Tex. App.—Dallas June 28, 2018, no pet.) (mem. op.).

A language change in the amended TCPA does not change the analytical framework for a basic practical point: “Before the 2019 amendments, the Texas Supreme Court held that the plaintiff’s petition is the best and all-sufficient evidence of the nature of the action for step one purposes. Hersh v. Tatum, 526 S.W.3d 462, 467 (Tex. 2017). The court said, ‘When it is clear from the plaintiff’s pleadings that the action is covered by the Act, the defendant need show no more.’ Id. We see no reason to conclude that the legislature intended to overrule Hersh when it changed the step one test from ‘shows by a preponderance of the evidence’ to “demonstrates.’ ‘Demonstrate’ means to ‘clearly show the existence or truth of (something) by giving proof or evidence.'” Brenner v. Centurion Logistics, No. 05-20-00308-CV (Dec. 10, 2020) (mem. op.).

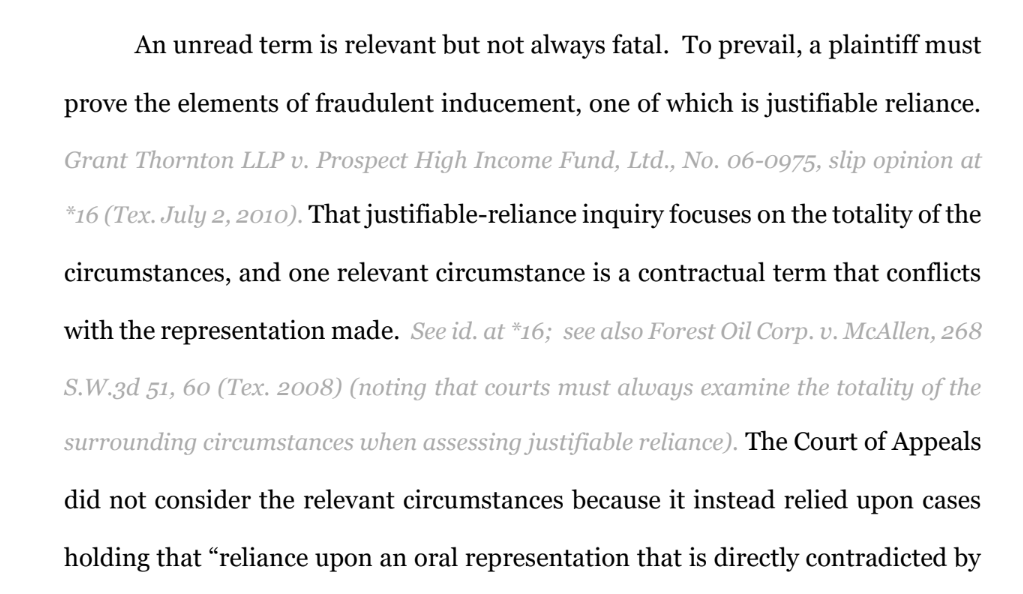

The Fifth Court reversed a judgment based on a jury finding of fraud in BBVA Compass v. Bagwell, No. 05-18-00860-CV (Dec. 14, 2020) (mem. op.), finding inadequate evidence of justifiable reliance. (LPHS represents the Intervenor appellees in this matter).

On rehearing, the Fifth Court reversed field and allowed a post-trial pleading amendment to stand, after previously holding that the amendment was invalid. Murphy v. Mejia Arcos, No. 05-18-01342-CV (Dec. 11, 2020). The relevant motion to amend was timely as it was filed before the entry of an amended judgment.

A new version of Tex. R. App. P. 49.3, about motions for rehearing, takes effect at the start of 2021. The new rule addresses the problem that surfaced after the 2018 elections, when many Justices who sat on a panel were no longer on their courts when the new calendar year begin. (I am quoted in this Law360 article about the rule amendment.)

A new version of Tex. R. App. P. 49.3, about motions for rehearing, takes effect at the start of 2021. The new rule addresses the problem that surfaced after the 2018 elections, when many Justices who sat on a panel were no longer on their courts when the new calendar year begin. (I am quoted in this Law360 article about the rule amendment.)

Yes, it’s kind of a pain, but it’s your vote, your voice, and your chance to be heard as to a widely-circulated attorney directory. The link to the Super Lawyers nomination site is here, and the deadline to make your nominations is December 21, 2020.

Yes, it’s kind of a pain, but it’s your vote, your voice, and your chance to be heard as to a widely-circulated attorney directory. The link to the Super Lawyers nomination site is here, and the deadline to make your nominations is December 21, 2020.

Vaughn-Riley v. Patterson illustrates the operation of the new, narrower definition of “matter of public concern” in the TCPA after last year’s amendments. The Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a TCPA motion in a dispute about the production of a play: “At the heart of this matter is whether the actors breached their contracts to perform the second Tyler show and the cause of the second Tyler show’s cancellation. Vaughn’s actions and communications regarding one isolated performance that did not go on as scheduled is simply not a subject of legitimate news interest; that is, a subject of general interest and of value and concern to the public.” In particular, the Court noted legislative history showing that the amendment was derived from a definition in Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011). It rejected an argument that the performed in question was a “limited public figure,” although that argument could be available in a future case. No. 05-20-00236-CV (Dec. 2, 2020) (mem. op.).

Vaughn-Riley v. Patterson illustrates the operation of the new, narrower definition of “matter of public concern” in the TCPA after last year’s amendments. The Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a TCPA motion in a dispute about the production of a play: “At the heart of this matter is whether the actors breached their contracts to perform the second Tyler show and the cause of the second Tyler show’s cancellation. Vaughn’s actions and communications regarding one isolated performance that did not go on as scheduled is simply not a subject of legitimate news interest; that is, a subject of general interest and of value and concern to the public.” In particular, the Court noted legislative history showing that the amendment was derived from a definition in Snyder v. Phelps, 562 U.S. 443 (2011). It rejected an argument that the performed in question was a “limited public figure,” although that argument could be available in a future case. No. 05-20-00236-CV (Dec. 2, 2020) (mem. op.).

Section 55.002 The Texas Estates Code provides: “In a contested probate or mental illness proceeding in probate court, a party is entitled to a jury trial as in other civil proceedings.” But while “the right to a jury trial ‘is inviolate and one of the greatest rights guaranteed by out Texas and United States Constitutions,’ … the right is not self executing, and even after the right is properly invoked, a party must act affirmatively to preserve a complaint concerning the right’s denial. Thus, to preserve error, a party who has properly perfected its jury trial right must either object on the record if the trial court proceeds without a jury or otherwise affirmatively indicate that it intends to stand on its perfected jury trial right.” In re Ruff Management Trust, No. 05-19-01505-CV (Dec. 3, 2020) (mem. op.). The appellant in Ruff waived any jury-trial right by not making timely objection in the trial court.

Section 55.002 The Texas Estates Code provides: “In a contested probate or mental illness proceeding in probate court, a party is entitled to a jury trial as in other civil proceedings.” But while “the right to a jury trial ‘is inviolate and one of the greatest rights guaranteed by out Texas and United States Constitutions,’ … the right is not self executing, and even after the right is properly invoked, a party must act affirmatively to preserve a complaint concerning the right’s denial. Thus, to preserve error, a party who has properly perfected its jury trial right must either object on the record if the trial court proceeds without a jury or otherwise affirmatively indicate that it intends to stand on its perfected jury trial right.” In re Ruff Management Trust, No. 05-19-01505-CV (Dec. 3, 2020) (mem. op.). The appellant in Ruff waived any jury-trial right by not making timely objection in the trial court.

Another preservation point from EYM Diner LP v. Yousef, No. 05-19-00636-CV (Nov. 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original), involves the structure of the charge on negligence. Defendant (ACCSC) complained that also argues it is entitled to rendition of judgment in its favor because the plaintiff (Youssef) did not object to the omission of  certain definitions from the charge, citing United Scaffolding v. Levine, 537 S.W.3d 463 (Tex. 2017). The Fifth Court disagreed:

certain definitions from the charge, citing United Scaffolding v. Levine, 537 S.W.3d 463 (Tex. 2017). The Fifth Court disagreed:

- “First, ACCSC’s reliance on United Scaffolding is misplaced because Yousef pleaded a general negligence claim against ACCSC and obtained a liability finding from the jury based on general negligence at trial. In United Scaffolding, the plaintiff, James Levine, pleaded one theory (premises liability) and obtained a jury finding on a different theory (general negligence).”

- “Second, United Scaffolding preserved its arguments that the verdict was based on an improper theory of recovery by filing a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict. Here, ACCSC filed no such motion and makes no such argument. ACCSC merely asserts charge error here. ACCSC waived any complaint about the charge by failing to object to the charge as discussed above. And, by failing to file a motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict or other qualifying post verdict motion raising this argument, ACCSC also waived any complaint that Yousef was not entitled to obtain a jury finding as to ACCSC’s general negligence.” (emphasis added in the above).

The Fifth Court granted mandamus relief in a proceeding related to the removal of a mechanic’s lien in In re J&S Utilities, No. 05-20-00696-CV (Nov. 24, 2020) (mem. op.), holding as follows:

The Fifth Court granted mandamus relief in a proceeding related to the removal of a mechanic’s lien in In re J&S Utilities, No. 05-20-00696-CV (Nov. 24, 2020) (mem. op.), holding as follows:

Abuse of discretion. “[T]he statute allows for an evidentiary hearing regardless of whether claimant elected to file a response. Although the trial court may have had the option of disregarding J&S Utilities’ response under its local rules, the trial court did not have the right to make a determination on submission and forfeit J&S Utilities’ right to an evidentiary hearing. For these reasons, we conclude the trial court abused its  discretion by denying J&S Utilities an evidentiary hearing.” (citation omitted).

discretion by denying J&S Utilities an evidentiary hearing.” (citation omitted).

Inadequate remedy. “The legislature provided for J&S Utilities’ due process rights by the statutory procedure that was enacted, but which the trial court denied to J&S Utilities and which cannot be cured by a subsequent appeal. Mandamus relief, however, will preserve J&S Utilities’ statutory right to an evidentiary hearing on the summary motion.”

“The trial judge in this case has a reputation for running a highly efficient courtroom in which he holds all parties to strict time limits for putting on their case. The record here shows this case was no exception. The truncated ‘charge conference’ appears to be one way in which the trial judge

moves cases along and gets cases to the jury quickly. While we applaud the trial judge’s efficiency and respect for the jurors’ time, the use of a global denial of objections and requests based solely on the parties’ pretrial submission of proposed jury charges does not preserve issues of charge error for appellate review. See, e.g., Clark v. Dillard’s, Inc., 460 S.W.3d 714, 729–30 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2015, no pet.); see also Tex. R. Civ. P. 272, 273, 274. The reason is simple; a proposed jury charge filed pretrial standing alone does not meet the preservation of error requirements of rules 272, 273, and 274.”

EYM Diner LP v. Yousef, No. 05-19-00636-CV (Nov. 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis in original)

Simon & Garfunkel’s The Sounds of Silence begins: “Hello darkness, my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again.” In In re Estate of Buchanan, however, the Fifth Court did not want to talk with the litigants again, after silence on a key issue in a previous appeal. The issue was who had the right to control certain funds based on a series of probate-court orders, which had involved a previous appeal to the Fifth Court. It held: “A reviewing court does not again pass upon any matter presented to, directly passed upon, or in effect disposed of by an earlier appeal to that court. An appellate court’s judgment is final not only in reference to the matters actually litigated, but as to all other matters the parties might have litigated and decided in the case. Thus, if James believed the trial court erred by declaring Jennifer has the superior right to the funds, he needed to raise the issue in that appeal.” No. 05-19-01473-CV (Nov. 19, 2020) (mem. op.).

Simon & Garfunkel’s The Sounds of Silence begins: “Hello darkness, my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again.” In In re Estate of Buchanan, however, the Fifth Court did not want to talk with the litigants again, after silence on a key issue in a previous appeal. The issue was who had the right to control certain funds based on a series of probate-court orders, which had involved a previous appeal to the Fifth Court. It held: “A reviewing court does not again pass upon any matter presented to, directly passed upon, or in effect disposed of by an earlier appeal to that court. An appellate court’s judgment is final not only in reference to the matters actually litigated, but as to all other matters the parties might have litigated and decided in the case. Thus, if James believed the trial court erred by declaring Jennifer has the superior right to the funds, he needed to raise the issue in that appeal.” No. 05-19-01473-CV (Nov. 19, 2020) (mem. op.).

In an echo (pun intended) of the Flakes litigation, the panel majority and a concurrence disagreed as to whether the appellant had adequately briefed its arguments; the majority finding that they had been appropriately presented and the concurrence holding a different view. For interested practitioners, the full text of the pertinent argument (relating to whether the underlying proceedings were an impermissible collateral attack on an earlier judgment) is reproduced in the concurrence. Eco Planet, LLC v. Ant Trading, 05-19-00239-CV (Nov. 16, 2020).

In an echo (pun intended) of the Flakes litigation, the panel majority and a concurrence disagreed as to whether the appellant had adequately briefed its arguments; the majority finding that they had been appropriately presented and the concurrence holding a different view. For interested practitioners, the full text of the pertinent argument (relating to whether the underlying proceedings were an impermissible collateral attack on an earlier judgment) is reproduced in the concurrence. Eco Planet, LLC v. Ant Trading, 05-19-00239-CV (Nov. 16, 2020).

The plaintiff sought a temporary injunction against a claimed trespass; the Fifth Court reversed on proof grounds: “[T]here is no evidence in the record that appellees have suffered or will suffer any injury or that any injury they would suffer is irreparable. Certainly the cost to repair or replace the fence can be adequately compensated in damages. And, while appellees argue trespass alone is an irreparable injury, this Court’s case law does not support that proposition. Appellees did not provide the trial court with any evidence that appellant trespassing on their property would cause probable, imminent, and irreparable injury. They did not show that appellant trespassing on their property would invade the possession of their land, destroy the use and enjoyment of their land, or cause potential loss of rights in real property.” WBW Holdings v. Clamon, No. 05-20-00397-CV (Nov. 12, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added, citations omitted).

The plaintiff sought a temporary injunction against a claimed trespass; the Fifth Court reversed on proof grounds: “[T]here is no evidence in the record that appellees have suffered or will suffer any injury or that any injury they would suffer is irreparable. Certainly the cost to repair or replace the fence can be adequately compensated in damages. And, while appellees argue trespass alone is an irreparable injury, this Court’s case law does not support that proposition. Appellees did not provide the trial court with any evidence that appellant trespassing on their property would cause probable, imminent, and irreparable injury. They did not show that appellant trespassing on their property would invade the possession of their land, destroy the use and enjoyment of their land, or cause potential loss of rights in real property.” WBW Holdings v. Clamon, No. 05-20-00397-CV (Nov. 12, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added, citations omitted).

“GPM asserted fraudulent transfer claims against all defendants. Given that GPM’s fraudulent transfer claim against Hossein involves the same facts and issues as the fraudulent transfer claims against Marjaneh and the two entities owned by them, the claim against Hossein was not properly severable. The trial court effectively severed a party, instead of a cause of action, and abused its discretion by doing so.” In re Glast Phillips & Murray, No. 05-20-00557-CV (Nov. 12, 2020) (mem. op.).

Among other issues addressed in Wal-Mart Stores v. Xerox State & Local Solutions, Inc., the Fifth Court examined whether indemnity obligations can give rise to third-party beneficiary status, and concluded that they did not on this record. No. 05-18-01421-CV (Nov. 12, 2020) (mem. op.). (LPHS represented Xerox, the successful appellee.)

Who knew? The federal bench in Houston just released an inspiring rendition of “We’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, revised to reflect life in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bravo!

Who knew? The federal bench in Houston just released an inspiring rendition of “We’ll Be Back” from Hamilton, revised to reflect life in the COVID-19 pandemic. Bravo!

As the Flying Dutchman (right) restlessly travels the Seven Seas, so does B.C. v. Steak N Shake travel the courts, most recently on remand from the Texas Supreme Court. The Fifth Court denied en banc review; concurrences by Justice Evans and Justice Schenck elaborated on the relevant scope of review (echoing their similar exchange in the Flakes case). Justice Evans succinctly summarized the respective positions: “[T]he record review I conducted was somewhat more than [Steak N Shake]’s view and quite a bit less than Justice Schenck’s view. … [U]ntil we receive contrary direction from the supreme court, we should continue to review the context of the record referenced by the parties, including in our review what the referenced-record contains, not merely the parties’ limited or inaccurate summary of the record.” No. 05-14-00649-CV (Aug. 3, 2020).

As the Flying Dutchman (right) restlessly travels the Seven Seas, so does B.C. v. Steak N Shake travel the courts, most recently on remand from the Texas Supreme Court. The Fifth Court denied en banc review; concurrences by Justice Evans and Justice Schenck elaborated on the relevant scope of review (echoing their similar exchange in the Flakes case). Justice Evans succinctly summarized the respective positions: “[T]he record review I conducted was somewhat more than [Steak N Shake]’s view and quite a bit less than Justice Schenck’s view. … [U]ntil we receive contrary direction from the supreme court, we should continue to review the context of the record referenced by the parties, including in our review what the referenced-record contains, not merely the parties’ limited or inaccurate summary of the record.” No. 05-14-00649-CV (Aug. 3, 2020).

In Merrill v. Curry, the Fifth Court reversed the grant of a TCPA motion to dismiss, and then declined to address a ruling on a partial Rule 91a motion that had also been appealed: “[W[e first consider the propriety and efficiency of addressing interlocutory issues after we have reversed the judgment dismissing the case. We have not located a case in which a party pursued, and a court addressed, the denial of a partial 91a motion under these circumstances. But this situation is analogous to the analysis employed when a party seeks review of a cross motion for partial summary judgment. As courts have explained, the denial of a motion for summary judgment is generally not appealable, except when both parties move for summary judgment and the trial court grants one and denies the other. In such a case, an appellate court reviews both motions and renders the judgment the trial court should have rendered. But, when a party moves for only partial summary judgment, the exception does not apply.” No. 05-19-01229-CV (Nov. 5, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

In Merrill v. Curry, the Fifth Court reversed the grant of a TCPA motion to dismiss, and then declined to address a ruling on a partial Rule 91a motion that had also been appealed: “[W[e first consider the propriety and efficiency of addressing interlocutory issues after we have reversed the judgment dismissing the case. We have not located a case in which a party pursued, and a court addressed, the denial of a partial 91a motion under these circumstances. But this situation is analogous to the analysis employed when a party seeks review of a cross motion for partial summary judgment. As courts have explained, the denial of a motion for summary judgment is generally not appealable, except when both parties move for summary judgment and the trial court grants one and denies the other. In such a case, an appellate court reviews both motions and renders the judgment the trial court should have rendered. But, when a party moves for only partial summary judgment, the exception does not apply.” No. 05-19-01229-CV (Nov. 5, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

The Texas Lawbook reports (not paywalled) the intermediate court of appeals election results, with these numbers on the Dallas races with roughly 95% completion:

Kaufman v. AmeriHealth Lab reviewed an important practical issue–does active participation in a TRO proceeding waive a potential special appearance? After reviewing the handful of Texas cases on the point, the Court concluded that a waiver occurred when, during the TRO hearing: “Kaufman’s counsel appeared without limiting his appearance and actively made arguments on Kaufman’s behalf, which included arguing he was not a signatory to the consulting agreement. AmeriHealth reminded the court that the parties retired to the jury room, at the court’s suggestion, to work out the expedited discovery requests. After their discussions, they proceeded on the record. The second half of the hearing in our appellate record is titled, ‘Rule 11

Kaufman v. AmeriHealth Lab reviewed an important practical issue–does active participation in a TRO proceeding waive a potential special appearance? After reviewing the handful of Texas cases on the point, the Court concluded that a waiver occurred when, during the TRO hearing: “Kaufman’s counsel appeared without limiting his appearance and actively made arguments on Kaufman’s behalf, which included arguing he was not a signatory to the consulting agreement. AmeriHealth reminded the court that the parties retired to the jury room, at the court’s suggestion, to work out the expedited discovery requests. After their discussions, they proceeded on the record. The second half of the hearing in our appellate record is titled, ‘Rule 11

Agreement Proceeding.'” No. 05-20-00504-CV (Oct. 30, 2020) (mem. op.).

“Jordan ignores a key component required for the exercise of a right to petition, namely, a communication under [TCPRC] section 27.001(4). … Contrary to Jordan’s argument, a nonmovant’s reference to a judicial proceeding in a petition does not necessarily establish that a movant has engaged in any communication constituting an exercise of a right to petition under section 27.001(4) or that the nonmovant’s claims are based on such communication.” Jordan v. JP Bent Tree, No. 05-19-01263-CV (Oct. 19, 2020).

“Jordan ignores a key component required for the exercise of a right to petition, namely, a communication under [TCPRC] section 27.001(4). … Contrary to Jordan’s argument, a nonmovant’s reference to a judicial proceeding in a petition does not necessarily establish that a movant has engaged in any communication constituting an exercise of a right to petition under section 27.001(4) or that the nonmovant’s claims are based on such communication.” Jordan v. JP Bent Tree, No. 05-19-01263-CV (Oct. 19, 2020).

Continuing to drive home the point from the recent Glassdoor litigation, the Fifth Court again reminded that: “Because the limitations period had run on the Estate’s anticipated claims before it filed its Rule 202 petition, the petition was moot, and the trial court should have dismissed the petition for want of jurisdiction.” In re Estate of Tobolowsky, No. 05-19-00073-CV (Oct. 20, 2020) (mem. op.).

Bickham v. Dallas County “consider[ed] whether ‘election watchers’—persons appointed to observe the conduct of an election under Chapter 33 of the Texas Election Code— have standing to pursue claims against certain election officials for alleged violations of chapter 33 and the Texas Administrative Code.” The panel majority concluded that they did not: “Appellants are not petition signers, and unlike the petition signers in [other cases], they have not shown an election interest that is distinct from voters at large. Although they allege impurity in the process, that interest is not distinct from voters at large, all of whom are presumed to want the election to be

Bickham v. Dallas County “consider[ed] whether ‘election watchers’—persons appointed to observe the conduct of an election under Chapter 33 of the Texas Election Code— have standing to pursue claims against certain election officials for alleged violations of chapter 33 and the Texas Administrative Code.” The panel majority concluded that they did not: “Appellants are not petition signers, and unlike the petition signers in [other cases], they have not shown an election interest that is distinct from voters at large. Although they allege impurity in the process, that interest is not distinct from voters at large, all of whom are presumed to want the election to be  conducted in compliance with the law.”

conducted in compliance with the law.”

A dissent saw the issue differently, reasoning: “The Legislature created the office of watcher, at least in substantial part, for the watcher to be available publicly to attest to the process, including in any later contest for office. … Whether one focuses on the right to express one’s opinion on the fairness of the process to the public via the print or electronic media or simply on the right to participate as a witness at a trial, either interest is legally cognizable.” No. 05-20-00560-CV (Oct. 23, 2020).

In a second visit to the Fifth Court on a discovery dispute involving claims of attorney-client privilege, the Court held: “In this case, neither party has put its attorney fees at issue. The Estate simply suspects that Topletz should be able to make payment on the judgment because he apparently has been able to pay his attorneys throughout this litigation. But that circumstance fails to fall within the kind of acceptable scenario that would permit discovery of the attorney fee information sought here.” In re Topletz, No. 05-20-00634-CV (Oct. 15, 2020) (mem. op.). The Court also reminded: “[N]either the rules of civil procedure nor case law requires evidence in support of an assertion relating to discovery when evidence is unnecessary to decide the matter. Here, evidence is not necessary to show that the requested information is not discoverable because this Court has already determined, as a matter of law, it is not.”

The Texas Lawbook recently held a candidate forum with all of the incumbents and challengers in this year’s three races for the Fifth Court. Its report on the forum is not behind a paywall and is interesting and informative reading.

The Texas Lawbook recently held a candidate forum with all of the incumbents and challengers in this year’s three races for the Fifth Court. Its report on the forum is not behind a paywall and is interesting and informative reading.

Mandamus relief was granted to compel a trial-court ruling about a motion for judgment nunc pro tunc in a criminal case when: “[R]elator’s third motion for judgment nunc pro tunc has been on file for roughly eleven months. Relator requested a ruling on the motion in the trial court approximately nine months ago. Although an unsigned memorandum was sent to relator, it stated that no ruling has yet been made. Under these circumstances, the trial court failed to fulfill its ministerial duty to rule on relator’s motion within a reasonable time, and relator lacks an adequate appellate remedy.” In re Williams, No. 05-20-00369-CV (Oct. 15, 2020) (mem. op.).

I was on a panel today for a great DAYL CLE program on jury charge conferences; you can see the one-hour presentation here!

In the context of a motion to extend an interlocutory-appeal deadline, the Fifth Court reminded: “We have previously concluded that intentionally waiting for a trial court to hear a motion for new trial is not a reasonable explanation.” Careington Int’l Corp. v. First Call Telemedicine LLC, No. 05-20-00841-CV (Oct. 12, 2020) (mem. op.).

In the context of a motion to extend an interlocutory-appeal deadline, the Fifth Court reminded: “We have previously concluded that intentionally waiting for a trial court to hear a motion for new trial is not a reasonable explanation.” Careington Int’l Corp. v. First Call Telemedicine LLC, No. 05-20-00841-CV (Oct. 12, 2020) (mem. op.).

Like a submarine occasionally surfacing from the deep, the concept of factual suffiency review (as distinct from legal sufficiency) occasionally emerges in family-law cases about parental termination. While In re M.T. unanimously affirms a termination judgment, a concurrence argued that the evidence on one of the statutory grounds was factually insufficient. No. 05-20-00450-CV (Oct. 5, 2020) (mem. op.).

Like a submarine occasionally surfacing from the deep, the concept of factual suffiency review (as distinct from legal sufficiency) occasionally emerges in family-law cases about parental termination. While In re M.T. unanimously affirms a termination judgment, a concurrence argued that the evidence on one of the statutory grounds was factually insufficient. No. 05-20-00450-CV (Oct. 5, 2020) (mem. op.).

A lurid invasion-of-privacy dispute offers a procedural reminder and substantive conclusion:

- Procedure: “MYR’s invasion of privacy claim was not “buried” in the pleading. Rather, her cause of action was clearly pleaded. She included additional jurisdictional facts in the affidavit attached to her response, to which BGC did not object, to support her burden. She did not add a new claim in her response. Accordingly, we consider whether BGC is subject to specific jurisdiction in Texas in light of MYR’s first amended pleading and response.”

- Substance: “BGS’s contacts in Texas with MYR were not random and isolated, but instead constituted purposeful, continued contacts in Texas over the course of a three-year relationship. And while he contends he did not seek any benefit from the state, he actively pursued a relationship with a Texas resident, whom he allegedly persuaded to provide intimate photos, and he likewise secretly took photos of her while in Texas. One may speculate about the benefit BGC received from the taking of such photos, but to say he received no benefit from a Texas resident is incredulous.”

BGC v. MYR, No. 05-20-00318-CV (Oct. 9. 2020) (mem. op.).

An unusual venue dispute led to a thorough review of the policies underlying the concept of “dominant jurisdiction” and the first-filed rule: “In resolving this dispute we must decide whether a plaintiff who initiates separate lawsuits in the same county against different defendants can claim dominant jurisdiction in one of those cases, after agreeing to transfer venue of that case to a different county and subsequently joining the defendant from the case still pending in the transferor county. Relators … assert that the transferred case lacks dominance over the interrelated case still pending in the original venue. We agree and conditionally grant the writ.” In re Equinor, No. 05-20-00578-CV (Oct. 7, 2020) (mem. op.).

An unusual venue dispute led to a thorough review of the policies underlying the concept of “dominant jurisdiction” and the first-filed rule: “In resolving this dispute we must decide whether a plaintiff who initiates separate lawsuits in the same county against different defendants can claim dominant jurisdiction in one of those cases, after agreeing to transfer venue of that case to a different county and subsequently joining the defendant from the case still pending in the transferor county. Relators … assert that the transferred case lacks dominance over the interrelated case still pending in the original venue. We agree and conditionally grant the writ.” In re Equinor, No. 05-20-00578-CV (Oct. 7, 2020) (mem. op.).

In Marble Ridge Capital v. Neiman-Marcus Group, the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a TCPA motion in a defamation action brought by Neiman-Marcus, pre-bankruptcy, against an investment fund. Among other holdings, the Court thoroughly surveyed Texas law about the judicial-communications privilege and held: “Based on this record, we conclude Marble Ridge did not satisfy its burden under section 27.005(d) regarding the judicial-communications privilege because Marble Ridge was not actually contemplating and giving serious consideration to a judicial proceeding when making its September 18, September 21, and September 25, 2018 communications.” No. No. 05-19-00443-CV (Sept. 30, 2020) (emphasis added). LPHS represented Neiman-Marcus in this matter.

In Marble Ridge Capital v. Neiman-Marcus Group, the Fifth Court affirmed the denial of a TCPA motion in a defamation action brought by Neiman-Marcus, pre-bankruptcy, against an investment fund. Among other holdings, the Court thoroughly surveyed Texas law about the judicial-communications privilege and held: “Based on this record, we conclude Marble Ridge did not satisfy its burden under section 27.005(d) regarding the judicial-communications privilege because Marble Ridge was not actually contemplating and giving serious consideration to a judicial proceeding when making its September 18, September 21, and September 25, 2018 communications.” No. No. 05-19-00443-CV (Sept. 30, 2020) (emphasis added). LPHS represented Neiman-Marcus in this matter.

The movants in GN Ventures v. Stanley won their argument that the TCPA applied to a motion in a dispute about arbitrability: “[E]ven though a request for a pre-arbitration temporary restraining order and temporary injunction merely seeks equitable remedies, and is not an independent cause of action, such a request is a ‘filing that requests . . . equitable relief’ and, therefore, a ‘legal action’ as defined by section 27.001(6). And because in this case, there is no underlying cause of action and appellants’ TCPA motion solely sought dismissal of the request for temporary restraining order and temporary injunction, that requested injunctive relief is the ‘claim’ the elements of which the Stanley affiliates must demonstrate a prima facie case by clear and specific evidence in the second step of the TCPA analysis we discuss below.” (citations omitted). Despite that win, however, they lost their motion because the nonmovants established a prima facie case for their requested injunctive relief. No. 05-19-01076-CV (Oct. 2, 2020).

The movants in GN Ventures v. Stanley won their argument that the TCPA applied to a motion in a dispute about arbitrability: “[E]ven though a request for a pre-arbitration temporary restraining order and temporary injunction merely seeks equitable remedies, and is not an independent cause of action, such a request is a ‘filing that requests . . . equitable relief’ and, therefore, a ‘legal action’ as defined by section 27.001(6). And because in this case, there is no underlying cause of action and appellants’ TCPA motion solely sought dismissal of the request for temporary restraining order and temporary injunction, that requested injunctive relief is the ‘claim’ the elements of which the Stanley affiliates must demonstrate a prima facie case by clear and specific evidence in the second step of the TCPA analysis we discuss below.” (citations omitted). Despite that win, however, they lost their motion because the nonmovants established a prima facie case for their requested injunctive relief. No. 05-19-01076-CV (Oct. 2, 2020).

An inartfully-drafted part of the expunction statute produced a remarkable 7-6 split of the en banc Fifth Court in Ex Parte Ferris, No. 05-19-00835-CV (Oct. 2, 2020). Charles Ferris pleaded guilty to DWI in 2015. Four years later, a jury found him not guilty in another DWI matter. Ferris sought expunction of the case in which he was acquitted, and ran headlong into a particularly awkward bit of statutory drafting.

If his two DWI cases formed a “criminal episode” as defined by Tex. Penal Code § 3.01, he could not receive expunction. The statute defines “criminal episode” as:

If his two DWI cases formed a “criminal episode” as defined by Tex. Penal Code § 3.01, he could not receive expunction. The statute defines “criminal episode” as:

… the commission of two or more offenses, regardless of whether the harm is directed toward or inflicted upon more than one person or item of property, under the following circumstances:

(1) the offenses are committed pursuant to the same transaction or pursuant to two or more transactions that are connected or constitute a common scheme or plan; or

(2) the offenses are the repeated commission of the same or similar offenses

(emphasis added). Part (1) did not apply, so the case turned on part (2).