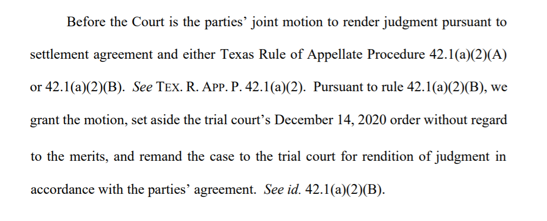

In the recent family law case of In re: B.W.S., this memorandum was held to not start the running of appellate deadlines; the Court notedd (among other things) how the parties reacted:

In the recent family law case of In re: B.W.S., this memorandum was held to not start the running of appellate deadlines; the Court notedd (among other things) how the parties reacted:

When a document such as the Memorandum here instructs the parties to prepare an appropriate final order, this is evidence that the trial court did not intend the document to be a final judgment. This is supported further by the fact the trial court signed the Final Order in this case three months later. Additionally, the parties did not treat the Memorandum as a final judgment below. Mother did not file post-judgment motions after the court sent the Memorandum; she filed them after the trial court signed the Final Order. And even though Father argues on appeal that the Memorandum was the final judgment, he did not argue that below, and he also filed a motion asking the court to sign a final order.

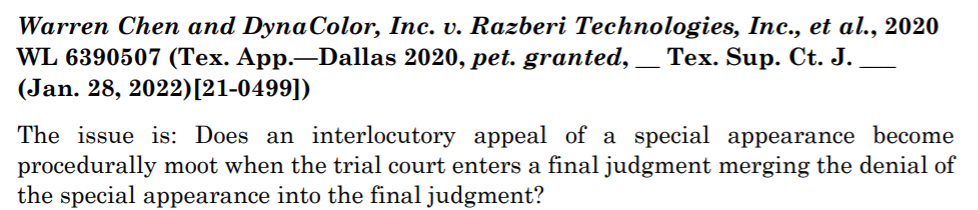

No. 05-15-01207-CV (Nov. 28, 2016) (mem. op.) (citation omitted). In contrast, in the recent family law case of In re B.D., a similar memorandum was held to constitute a judgment and start the running of appellate deadlines; discounting (among other things) how the parties reacted to it:

“Despite the trial court’s hearings to consider appellee’s motion to sign an order and its subsequent order, we conclude the memorandum substantially complies with the requisites of a formal judgment to be accorded final judgment status triggering the appellate deadline.”

No. 05-17-00674-CV (Aug. 31, 2017).

The key distinction between these opinions seems to be the inclusion of express language that the memorandum is not intended as a judgment, and that requests the parties to prepare draft judgments. This practice echoes the general custom endorsed by Lehmann v. Har-Con Corp., 39 S.W.3d 191 (Tex. 2001), of including “language of finality” in a ruling intended to be a final judgment. Of course, even under Lehmann, the substance controls rather than the “magic words,” so this area looks to be one that will continue to pose practical challenges. (SPECIAL THANKS to Hon. Emily Miskel of the 470th District Court in Collin County, who alerted me to these cases on her informative Twitter feed.)

er 23 Order indicates the trial [judge] intended for its September 22 Order to constitute a final and appealable judgment that disposed of all claims.” Unfortunately for the appeal, however, the Fifth Court noted (1) “factual recitations or reasons preceding the decretal portion of a judgment form no part of the judgment itself,” and (2) “the October 23 Order cannot constitute a final judgment because it lacks the decretal language typically seen in a judgment” [such as “ordered, adjudged, and decreed,” etc.]. Because of these shortcomings with the October 23 Order, and the September 22 Order’s failure to address all causes of action or include Lehmann finality language, there was no final judgment and thus no appellate jurisdiction. No. 05-17-01228-CV (Dec. 18, 2018) (mem. op.)

er 23 Order indicates the trial [judge] intended for its September 22 Order to constitute a final and appealable judgment that disposed of all claims.” Unfortunately for the appeal, however, the Fifth Court noted (1) “factual recitations or reasons preceding the decretal portion of a judgment form no part of the judgment itself,” and (2) “the October 23 Order cannot constitute a final judgment because it lacks the decretal language typically seen in a judgment” [such as “ordered, adjudged, and decreed,” etc.]. Because of these shortcomings with the October 23 Order, and the September 22 Order’s failure to address all causes of action or include Lehmann finality language, there was no final judgment and thus no appellate jurisdiction. No. 05-17-01228-CV (Dec. 18, 2018) (mem. op.)