The London Underground reminds its riders to “Mind the Gap” so they do not trip when entering or exiting a train. The Fifth Circuit’s new typography places a notable gap between paragraphs and footnotes. While this sort of line-spacing does not have a technical label like “kerning,” it is nevertheless an important part of the overall look and feel of a piece of legal writing. What are your thoughts on inter-paragraph line spacing?

The London Underground reminds its riders to “Mind the Gap” so they do not trip when entering or exiting a train. The Fifth Circuit’s new typography places a notable gap between paragraphs and footnotes. While this sort of line-spacing does not have a technical label like “kerning,” it is nevertheless an important part of the overall look and feel of a piece of legal writing. What are your thoughts on inter-paragraph line spacing?

After an earlier dispute about the merits of an interlocutory stay, the Fifth Court reached the substantive issue of arbitrability in Baby Dolls v. Sotero, a personal-injury lawsuit about a serious car accident involving two dancers after they left work. The key question was the interplay of the terms “License” and “Agreement” in the relevant contract; the panel majority concluded: “On this record, we conclude the trial court could have properly determined the parties’ minds could not have met regarding the contract’s subject matter and all its essential terms such that the contract is not an enforceable agreement. Consequently, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by denying the motions to compel arbitration.” (citations omitted). A dissent disputed whether that conclusion was a proper legal basis to deny a motion to compel arbitration, and would have reached a different result about the construction of the parties’ contract. No. 05-19-01443-CV (Aug. 21, 2020) (mem. op.)

After an earlier dispute about the merits of an interlocutory stay, the Fifth Court reached the substantive issue of arbitrability in Baby Dolls v. Sotero, a personal-injury lawsuit about a serious car accident involving two dancers after they left work. The key question was the interplay of the terms “License” and “Agreement” in the relevant contract; the panel majority concluded: “On this record, we conclude the trial court could have properly determined the parties’ minds could not have met regarding the contract’s subject matter and all its essential terms such that the contract is not an enforceable agreement. Consequently, the trial court did not abuse its discretion by denying the motions to compel arbitration.” (citations omitted). A dissent disputed whether that conclusion was a proper legal basis to deny a motion to compel arbitration, and would have reached a different result about the construction of the parties’ contract. No. 05-19-01443-CV (Aug. 21, 2020) (mem. op.)

In re: Sakyi reminds: “the unique and serious circumstances created by the COVID pandemic require flexibility and adaptability in all aspects of our legal system.” the Court went on to grant mandamus relief about the the denial of a motion for continuance, observing: “In this case, all factors weigh in favor of concluding that the trial court’s denial of the continuance was an abuse of discretion. First, this case is not old; at the time the continuance was sought, the case had been on file for less than a year. Second, the discovery sought is central to the underlying divorce suit since RPI’s marriages, if overlapping, may affect the determination of what property is in the marital estate at issue and raise equitable considerations of possible fraud. Indeed, the trial court acknowledged that the conflicting marriage dates created an issue of fact. Third, Relator’s counsel submitted an affidavit describing her diligent efforts to obtain the necessary discovery before trial.” No. 05-20-00574-CV (Aug. 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

In re: Sakyi reminds: “the unique and serious circumstances created by the COVID pandemic require flexibility and adaptability in all aspects of our legal system.” the Court went on to grant mandamus relief about the the denial of a motion for continuance, observing: “In this case, all factors weigh in favor of concluding that the trial court’s denial of the continuance was an abuse of discretion. First, this case is not old; at the time the continuance was sought, the case had been on file for less than a year. Second, the discovery sought is central to the underlying divorce suit since RPI’s marriages, if overlapping, may affect the determination of what property is in the marital estate at issue and raise equitable considerations of possible fraud. Indeed, the trial court acknowledged that the conflicting marriage dates created an issue of fact. Third, Relator’s counsel submitted an affidavit describing her diligent efforts to obtain the necessary discovery before trial.” No. 05-20-00574-CV (Aug. 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

Sometimes to state the issue is to decide it. For example, the Fifth Court’s opinion in Ruff v. Ruff began: “A pivotal question we address is whether a party can initiate an arbitration proceeding pursuant to a specific arbitration agreement, demand that a signatory to that agreement be compelled to participate in that arbitration, and then disavow the resulting award by alleging that he (the initiating party) did not agree to arbitrate according to that arbitration agreement.” The Court answered that question “no,” reviewing the invited-error and several estoppel doctrines. No. 05-18-00326-CV (Aug. 11, 2020).

Sometimes to state the issue is to decide it. For example, the Fifth Court’s opinion in Ruff v. Ruff began: “A pivotal question we address is whether a party can initiate an arbitration proceeding pursuant to a specific arbitration agreement, demand that a signatory to that agreement be compelled to participate in that arbitration, and then disavow the resulting award by alleging that he (the initiating party) did not agree to arbitrate according to that arbitration agreement.” The Court answered that question “no,” reviewing the invited-error and several estoppel doctrines. No. 05-18-00326-CV (Aug. 11, 2020).

Damages were not established in In the Interest of MGG, No. 05-19-00777-CV (Aug. 10, 2020) (mem. op.), when:

“Ms. Gatewood does not dispute that Mr. Gustafson and his employer paid the withheld amounts to the IRS to cover the taxes from the transactions. Nor does she dispute that, if Mr. Gustafson instead paid her 100% of the gross proceeds, she would have to pay those taxes. The only theory of harm Ms. Gatewood advanced in the trial is that, by withholding and paying taxes based on his own tax rate instead of hers, Mr. Gustafson forced her to pay taxes at a higher rate. The proper measure of damages for that harm, however, is the difference between the taxes she would have paid at her purportedly lower tax rate and the amount Mr. Gustafson paid the IRS. To prove Mr. Gustafson harmed her in that manner, Ms. Gatewood had to prove there was a disparity between their tax rates.

Ms. Gatewood refused to turn over her tax records during discovery and chose not to present evidence establishing her tax rate at the trial. The only record evidence directly touching upon Ms. Gatewood’s tax rate is her affirmative response to a hypothetical question asking whether she was ‘at least hopeful’ her tax rate would be lower if she received the money Mr. Gustafson paid the IRS. That conclusory response, premised on Ms. Gatewood’s hope or belief, is insufficient to show Ms. Gatewood’s tax rate would have been lower.” (emphasis added).

In re Smith held that the statutory stay of certain discovery in health-liability claims did not apply to policies that nursing homes are required to make publicly available. As to the availability of mandamus relief, the Court observed: “It is well settled that mandamus relief is appropriate when the trial court

In re Smith held that the statutory stay of certain discovery in health-liability claims did not apply to policies that nursing homes are required to make publicly available. As to the availability of mandamus relief, the Court observed: “It is well settled that mandamus relief is appropriate when the trial court

abuses its discretion by ordering discovery precluded by section 74.351(s). However, it is not clear whether the same is true when the trial court prohibits discovery that the statute permits.” (emphasis in original, citation omitted). The Court concluded that it was appropriate because of the potential effect on the statutorily-required expert report. (While the Court cites, inter alia, a general proposition from the Texas Supreme Court about mandamus relief, it remains to be seen how much weight this case will have in other settings without a similar expert report requirement.) No. 05-20-00497-CV (Aug. 12, 2020) (mem. op.).

McGuire-Sobrino v. TX Cannalliance LLC presents a mini-course on effective protection of business information. Cannalliance sued McGuire-Sobrino, a former contractor, for restricting its access to its website and other digital assets. The Fifth Court addressed

McGuire-Sobrino v. TX Cannalliance LLC presents a mini-course on effective protection of business information. Cannalliance sued McGuire-Sobrino, a former contractor, for restricting its access to its website and other digital assets. The Fifth Court addressed

- Rule 683. The temporary injunction made adequately-detailed findings, which the Court quoted largely verbatim;

- Irreparable injury. Rejecting the argument that Cannalliance’s proof of irreparable injury showed only “a fear of possible contingencies,” the Court credited testimony of its managing member that “his inability to control Cannalliance’s digital assets and website is ‘crippling our ability to market and promote our events, to sell tickets to support the business’ and … ‘can smear the public perception and paint a bad picture of the ability to have control over our business.'”

- Likelihood of success. Cannaliance showed a likelihood of success on claims for conversion and trademark infringement; and

- Status quo. The injunction preserved the status quo by “returning the parties to their pre-September 26, 2019 status” (the date when Cannalliance showed it no longer had full access to its digital assets).

No. 05-19-01261-CV (Aug. 10, 2020) (mem. op.).

Palladium Metal Recycling v. 5G Metals reminds: “Interlocutory appeals are only available from orders denying TCPA motions, not from orders granting them.” As to that granted motion, the Court also observed in a footnote: “Notably, in the event the trial court’s ruling has not become final and appealable, the trial court retains jurisdiction to vacate its order regarding St. Charles should it decide to do so.” No. 05-19-00482-CV (July 28, 2020) (mem. op.)

The Fifth Court reversed an award of sanctions, based on the trial court’s exercise of its inherent power, in In re Estate of Powell: “The trial court’s orders reflect that it made the attorney’s fees award as a sanction for Douglas’s and Putnam’s bad faith violation of the rule 11 agreement. Although there is some evidence supporting the trial court’s finding that Douglas and Putnam acted in bad faith, the trial court did not also find or conclude that Douglas’s and Putnam’s bad faith conduct significantly interfered with the court’s ‘legitimate exercise of its core functions.’ Consequently, we conclude the trial court abused its discretion by imposing the sanction against Douglas and Putnam.” No. 05-19-00689-CV (Aug. 4, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted) (applying Union Carbide Corp. v. Martin, 349 S.W.3d 137 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2011, no pet.)

The Fifth Court reversed an award of sanctions, based on the trial court’s exercise of its inherent power, in In re Estate of Powell: “The trial court’s orders reflect that it made the attorney’s fees award as a sanction for Douglas’s and Putnam’s bad faith violation of the rule 11 agreement. Although there is some evidence supporting the trial court’s finding that Douglas and Putnam acted in bad faith, the trial court did not also find or conclude that Douglas’s and Putnam’s bad faith conduct significantly interfered with the court’s ‘legitimate exercise of its core functions.’ Consequently, we conclude the trial court abused its discretion by imposing the sanction against Douglas and Putnam.” No. 05-19-00689-CV (Aug. 4, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted) (applying Union Carbide Corp. v. Martin, 349 S.W.3d 137 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2011, no pet.)

“[Tex. R. Civ. P.] 11 provides that ‘no agreement between attorneys or parties touching any suit pending will be enforced unless it be in writing, signed and filed with the papers as part of the record, or unless it be made in open court and entered of record.’ The purpose of the rule is to relieve the courts of the necessity of resolving disputes over the terms of oral agreements relating to pending suits. As explained in [Anderson v. Cocheu], however, in enforcing rule 11 [agreements] ‘the Texas Supreme Court has been mindful of the fact that the rule may be said to abridge the substantive right of persons to enter into oral contracts.’ Consequently, courts have balanced the purpose of the rule with the ability to make oral agreements, resulting in recognition of certain equitable exceptions to rule 11’s writing requirement. One exception to the writing requirement arises when the oral agreement is undisputed. ‘In cases where the existence of the agreement and its terms are not disputed, the agreement may be enforced despite its literal noncompliance with the rule.’” In re Estate of Powell, No. 05-19-00689-CV (Aug. 4, 2020) (mem. op.).

“[Tex. R. Civ. P.] 11 provides that ‘no agreement between attorneys or parties touching any suit pending will be enforced unless it be in writing, signed and filed with the papers as part of the record, or unless it be made in open court and entered of record.’ The purpose of the rule is to relieve the courts of the necessity of resolving disputes over the terms of oral agreements relating to pending suits. As explained in [Anderson v. Cocheu], however, in enforcing rule 11 [agreements] ‘the Texas Supreme Court has been mindful of the fact that the rule may be said to abridge the substantive right of persons to enter into oral contracts.’ Consequently, courts have balanced the purpose of the rule with the ability to make oral agreements, resulting in recognition of certain equitable exceptions to rule 11’s writing requirement. One exception to the writing requirement arises when the oral agreement is undisputed. ‘In cases where the existence of the agreement and its terms are not disputed, the agreement may be enforced despite its literal noncompliance with the rule.’” In re Estate of Powell, No. 05-19-00689-CV (Aug. 4, 2020) (mem. op.).

In re Commitment of Barnes, No. 05-19-00702-CV (Aug. 5, 2020) (mem. op.), involved a challenge to a voir dire limitation. The trial was to determine whether Barnes should be civilly committed as a sexual predator. His counsel sought to ask these voir dire questions, which the trial court found to be improper “commitment” questions:

In re Commitment of Barnes, No. 05-19-00702-CV (Aug. 5, 2020) (mem. op.), involved a challenge to a voir dire limitation. The trial was to determine whether Barnes should be civilly committed as a sexual predator. His counsel sought to ask these voir dire questions, which the trial court found to be improper “commitment” questions:

“If you hear evidence of a pedophilic disorder diagnosis, if you hear evidence of child victims, are you going to automatically assume that the person has a behavioral abnormality as defined by what you hear in this case?”

– and –

“If you are presented with evidence by an expert that the diagnosis of a person is pedophilic disorder, are you going to automatically assume that that person has a condition that by [a]ffecting the emotional or volitional capacity predisposes the person to commit a sexually violent offense to the extent that they become a menace to the

health and safety of another person?

The Fifth Court found that this ruling was erroneous, but also no harm because, inter alia, a similar question was allowed: “If you hear evidence of child victims,

is that going to make it to where you turn everything off and don’t listen to the rest

of the facts and you are done? Anyone?”

To review the propriety of the question, the Court applied a 3-part test based on the Court of Criminal Appeals’ Standefer opinion:

To review the propriety of the question, the Court applied a 3-part test based on the Court of Criminal Appeals’ Standefer opinion:

- “[W]hether this is a commitment question, meaning one to which ‘one or more of the possible answers is that the prospective juror would resolve or refrain from resolving an issue in the case on the basis of one or more facts contained in the question.’” The Court held that it was, because “one answer is that the juror would automatically find a behavioral abnormality if the juror hears evidence of pedophilic disorder or child victims.”

- “[I]s this commitment question proper, meaning one of the possible answers gives rise to a valid challenge for cause.“ The Court held that it was, noting: “The law requires a ‘certain type of commitment from jurors’ in every trial, and that includes following the law.” From there, the Court held: “If a juror answered that she would stop listening to additional evidence regarding ‘behavioral abnormality’ after hearing a diagnosis of pedophilic disorder or hearing of prior child victims, that juror would be committing to not listening to all the evidence. It would not be a ‘fact-specific opinion,’ but rather evidence of a disqualifying and ‘improper subject-matter bias.'”

- “[D]oes the question contain ‘only those facts necessary to test whether a prospective juror is challengeable for cause.'” Here, where “[t]he subject matter of the case was child victims and a pedophilic disorder diagnosis,” the Court concluded: “The question added no more, especially in light of what the State had previously introduced to the venire, and thus contained only the facts necessary to test whether the juror is challengeable for cause.”

The ABA House of Delegates has recently adopted a comprehensive set of best practices for litigation funding–an important topic in modern law practice.

The ABA House of Delegates has recently adopted a comprehensive set of best practices for litigation funding–an important topic in modern law practice.

The plaintiffs in In re Outreach Housing sought to enforce a (revived) 2006 default judgment that was not final under the applicable standards. The Fifth Court granted mandamus relief as to the trial court’s denial of the defendants’ motion to stay. It found an abuse of discretion in that decision, with irreparable

The plaintiffs in In re Outreach Housing sought to enforce a (revived) 2006 default judgment that was not final under the applicable standards. The Fifth Court granted mandamus relief as to the trial court’s denial of the defendants’ motion to stay. It found an abuse of discretion in that decision, with irreparable  consequences arising from the denial of a meaningful appeal from the 2006 judgment, and some parties’ lack of a meaningful trial. The Court acknowledged a technical point about a potential interlocutory appeal from the denial of the motion, but found that matter too speculative to deny mandamus relief in these circumstances. No. 05-20-00431-CV (July 30, 2020).

consequences arising from the denial of a meaningful appeal from the 2006 judgment, and some parties’ lack of a meaningful trial. The Court acknowledged a technical point about a potential interlocutory appeal from the denial of the motion, but found that matter too speculative to deny mandamus relief in these circumstances. No. 05-20-00431-CV (July 30, 2020).

The Governor has directed that certain government flags fly at half-staff on August 1 in the memory of Justice Bridges.

(An expanded version of this post appears this week in the Texas Lawbook.)

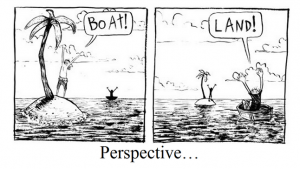

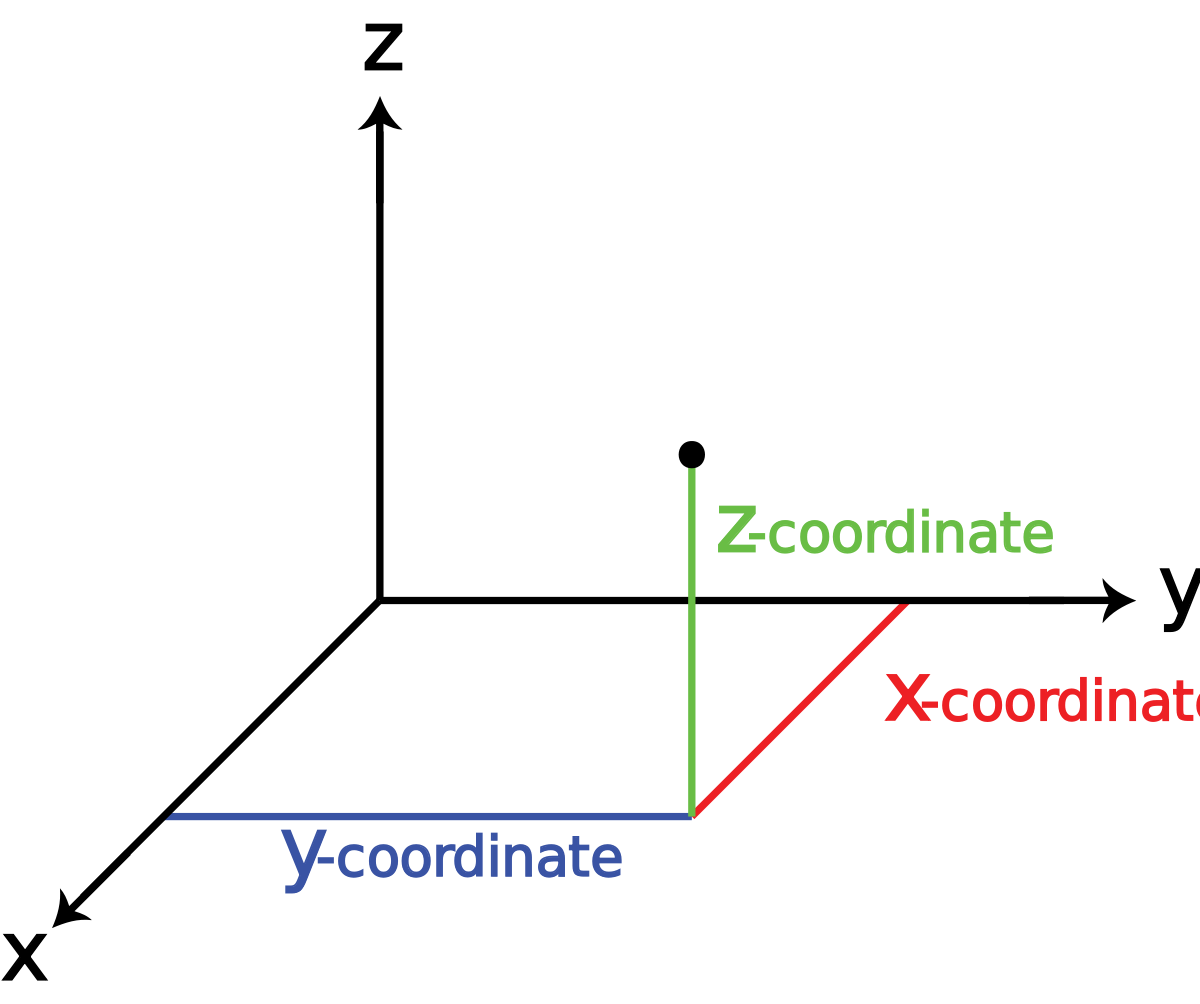

Cyberpunk stories often describe the physical world as meatspace, as distinct from the online world of cyberspace. Litigation forces courts to consider the connection between the two “spaces” when a party contests the exercise of personal jurisdiction based on online activity. While precise definition of a website’s functionality can involve technical terms, the jurisdiction analysis involves familiar concepts, as illustrated by Shopstyle, Inc. & Popsugar, Inc. v. Rewardstyle, Inc.:

Purposeful availment. “[W]hen using the Shop feature, the user cannot purchase products on the PopSugar website but instead follows links to the websites of affiliated third-party retailers. In other words, the ‘user cannot consummate a commercial transaction online without accessing and logging-into a third-party website.'”

Operative facts. “Whether PopSugar’s website is available in Texas or whether links to Texas-based retailers are available on PopSugar’s website is unrelated to the operative facts as alleged by rewardStyle. The record contains no allegations or evidence of which we are aware that the alleged operative conduct occurred in Texas or that it has anything to do with Texas, apart from the fact that rewardStyle and one of its influencers are located here.”

Third-party activity. “[E]even if another party creating ShopStyle links and adding them to allegedly misappropriated images was considered an affirmative act by ShopStyle (and we are not so concluding), permitting hyperlinks to the websites of third-party Texas-based retailers where products can be purchased “would not demonstrate, by itself, that [ShopStyle] controls the third-party sufficiently for sales from the third-party’s website to constitute ‘contacts’ by [ShopStyle].”

Third-party activity. “[E]even if another party creating ShopStyle links and adding them to allegedly misappropriated images was considered an affirmative act by ShopStyle (and we are not so concluding), permitting hyperlinks to the websites of third-party Texas-based retailers where products can be purchased “would not demonstrate, by itself, that [ShopStyle] controls the third-party sufficiently for sales from the third-party’s website to constitute ‘contacts’ by [ShopStyle].”

No. 05-19-00736-CV (July 21, 2020) (mem. op.). Of procedural interest, this case arose from a presuit discovery request under Tex. R. Civ. P. 202.

The legal structure of local government has received great scrutiny this year as the COVID-19 pandemic has forced all levels of state government to review the emergency powers granted by the Texas Government Code. Less-trendy but also-fundamental aspects of local government operation were at issue in Carruth v. Henderson, when a citizen sought mandamus relief to require the City of Plano to consider a referendum petition about the City’s comprehensive development plan. The Fifth Court expressed sympathy for the City’s position, but found that under the applicable statutes, it had a ministerial duty to accept the petition as “neither the [City] Charter nor the general law has withdrawn comprehensive plans either expressly or by necessary implication from the field in which the referendum process operates …” No. 05-19-01195-CV (July 22, 2020). I am quoted in an excellent column about this situation by Sharon Grigsby in the July 28 Dallas Morning News.

The legal structure of local government has received great scrutiny this year as the COVID-19 pandemic has forced all levels of state government to review the emergency powers granted by the Texas Government Code. Less-trendy but also-fundamental aspects of local government operation were at issue in Carruth v. Henderson, when a citizen sought mandamus relief to require the City of Plano to consider a referendum petition about the City’s comprehensive development plan. The Fifth Court expressed sympathy for the City’s position, but found that under the applicable statutes, it had a ministerial duty to accept the petition as “neither the [City] Charter nor the general law has withdrawn comprehensive plans either expressly or by necessary implication from the field in which the referendum process operates …” No. 05-19-01195-CV (July 22, 2020). I am quoted in an excellent column about this situation by Sharon Grigsby in the July 28 Dallas Morning News.

Long-serving Justice David Bridges was killed this weekend when his car was struck by a drunk driver. This shocking news is a loss for all North Texas.

Long-serving Justice David Bridges was killed this weekend when his car was struck by a drunk driver. This shocking news is a loss for all North Texas.

In addition to a thorough review of Batson law as applied to Hispanic potential jurors, Murphy v. Mejia Arcos provides a powerful example of the rules about post-trial pleading amendments.

In addition to a thorough review of Batson law as applied to Hispanic potential jurors, Murphy v. Mejia Arcos provides a powerful example of the rules about post-trial pleading amendments.

On the one hand, “pursuant to rules 63 and 66 of the Texas Rules of Civil Procedure, a trial court must allow a postverdict amendment that increases the amount of damages sought in the pleadings to that found by the jury unless the opposing party presents evidence of prejudice or surprise.” (emphasis added)

But at the same time, “a trial court cannot grant a motion for leave to amend the pleadings after the court signs the judgment.”

Accordingly, the trial court abused its discretion when it (1) signed a final judgment, (2) granted the plaintiff’s motion to amend the pleadings, and then (3) signed a new judgment without an order setting aside the first one. “Because the trial court never signed a written order vacating the August 9, 2018 final judgment, its oral pronouncement [about vacating that judgment] was ineffective, so the August 9,

2018 judgment continued in force and effect. . . . [A]t all times after August 9, 2018, there has always been a final judgment in this case. Therefore, the trial court did not follow the guiding principles of law that it cannot grant leave to file an amended pleading after judgment.”

As a result, the judgment was reduced to $200,000 (the maximum amount sought specified by the plaintiff’s trial pleading) from the $1,000,000 awarded in the jury’s verdict. No. 05-18-01342-CV (July 17, 2020).

The principle is easy enough to state — because the mandatory-venue statute about injunctive relief “is limited to suits ‘in which the relief sought is purely or primarily injunctive[,] . . . it does not apply when the injunctive relief is ancillary to the other relief sought . . . where the injunctive relief is requested simply to maintain the status

The principle is easy enough to state — because the mandatory-venue statute about injunctive relief “is limited to suits ‘in which the relief sought is purely or primarily injunctive[,] . . . it does not apply when the injunctive relief is ancillary to the other relief sought . . . where the injunctive relief is requested simply to maintain the status

quo pending resolution of the lawsuit.” In re: Zidan shows that reasonable minds can differ about its application, however. The majority opinion saw the plaintiff’s request for injunctive relief as ancillary to the central dispute about the governance of a business entity; the dissent saw it as sufficiently central to implicated the statute. The Fifth Court’s judgment conditionally granted mandamus relief with respect to a Collin County judge’s decision to abate a first-filed case in favor of a Harris County matter. No. 05-20-00595-CV (July 15, 2020) (mem. op.)

Please check out my new podcast, Coale Mind, where once a week I talk about constitutional and other legal issues of the day. This forum lets me get into more detail than other media appearances, while also approaching issue from a less technical perspective than blogging and other professional writing. I hope you enjoy it and choose to subscribe! Available on Spotify, Apple, and other such services.

Please check out my new podcast, Coale Mind, where once a week I talk about constitutional and other legal issues of the day. This forum lets me get into more detail than other media appearances, while also approaching issue from a less technical perspective than blogging and other professional writing. I hope you enjoy it and choose to subscribe! Available on Spotify, Apple, and other such services.

While jury selection is a critical and at times outcome-determinative part of trial, appellate opinions on voir dire issues are scarce – trial judges have considerable discretion in such matters and harm is difficult to establish. All the more reason for trial lawyers to carefully review Murphy v. Mejia Arcos, a painstaking analysis of Batson challenges to peremptory strikes of Hispanic jurors. Carefully applying the precedent in the area, the Fifth Court found no abuse of discretion by the trial court in sustaining two such challenges in a personal-injury trial. The analysis is of obvious statewide significance for Texas practice, offering a practical summary of the current Batson procedural framework, and having important policy consequences for an infrequently-reviewed aspect of civil trial practice. No. 05-18-01342-CV (July 17, 2020).

While jury selection is a critical and at times outcome-determinative part of trial, appellate opinions on voir dire issues are scarce – trial judges have considerable discretion in such matters and harm is difficult to establish. All the more reason for trial lawyers to carefully review Murphy v. Mejia Arcos, a painstaking analysis of Batson challenges to peremptory strikes of Hispanic jurors. Carefully applying the precedent in the area, the Fifth Court found no abuse of discretion by the trial court in sustaining two such challenges in a personal-injury trial. The analysis is of obvious statewide significance for Texas practice, offering a practical summary of the current Batson procedural framework, and having important policy consequences for an infrequently-reviewed aspect of civil trial practice. No. 05-18-01342-CV (July 17, 2020).

“Care Tecture contends the trial court could not consider the [Mediated Settlement Agreement] because it was not physically attached to the motion or an affidavit. Matheson argues that the MSA was properly before the court because it was on file with the court at the time of the summary judgment hearing, referenced in the motion for summary judgment, and authenticated by the affidavits. We agree with Matheson. See Kastner v. Jenkens & Gilchrist, 231 S.W.3d 571, 581 (Tex.App.—Dallas 2007, no pet.) (noting that the rules “do not require that summary judgment evidence be physically attached to the motion”). Care Tecture v. Matheson Commercial Properties, No. 19-00591-CV (June 30, 2020) (mem. op.)

Shylock sought to exact a pound of flesh from a debtor in The Merchant of Venice (right, played by Al Pacino). In Selinger v. City of McKinney, a form of taking called an “exaction” was at issue, when “[Plaintiffs] alleged that the City denied Selinger’s plat because he refused to agree to a contingent $482,000 payment as a condition of plat approval. Those facts amount to an exaction … .” The conditional nature of an exaction leads to unusual questions about ripeness and mootness, as well as governmental-immunity issues, all of which were resolved by the Fifth Court substantially in favor of the Plaintiffs. No. 05-19-00545-CV (July 1, 2020) (mem. op.)

Shylock sought to exact a pound of flesh from a debtor in The Merchant of Venice (right, played by Al Pacino). In Selinger v. City of McKinney, a form of taking called an “exaction” was at issue, when “[Plaintiffs] alleged that the City denied Selinger’s plat because he refused to agree to a contingent $482,000 payment as a condition of plat approval. Those facts amount to an exaction … .” The conditional nature of an exaction leads to unusual questions about ripeness and mootness, as well as governmental-immunity issues, all of which were resolved by the Fifth Court substantially in favor of the Plaintiffs. No. 05-19-00545-CV (July 1, 2020) (mem. op.)

Armbrister’s car was repossessed. She sued the lender because it had unlawfully refused to deduct her payment from a Federal Government Federal Reserve Bank account. She had acquired the rights to this account, she alleged, because of her work for the FBI, the NSA, and the Defense Department on an artificial intelligence team; those agencies had authorized her by neural communication to pay all of her bills from an account at the Federal Reserve. Unfortunately for Armbrister, her claim did not satisfy the demands of Tex. R. Civ. P. 91a, and the Fifth Court affirmed. Armbirster v. American Honda Finance Corp., No. 05-19-00593-CV (July 10, 2020) (mem. op.) The opinion did not address whether neural communication satisfies the statute of frauds, or whether the relevant government agencies may have immunity defenses to fraudulent-inducement claims by Armbrister.

Armbrister’s car was repossessed. She sued the lender because it had unlawfully refused to deduct her payment from a Federal Government Federal Reserve Bank account. She had acquired the rights to this account, she alleged, because of her work for the FBI, the NSA, and the Defense Department on an artificial intelligence team; those agencies had authorized her by neural communication to pay all of her bills from an account at the Federal Reserve. Unfortunately for Armbrister, her claim did not satisfy the demands of Tex. R. Civ. P. 91a, and the Fifth Court affirmed. Armbirster v. American Honda Finance Corp., No. 05-19-00593-CV (July 10, 2020) (mem. op.) The opinion did not address whether neural communication satisfies the statute of frauds, or whether the relevant government agencies may have immunity defenses to fraudulent-inducement claims by Armbrister.

On the facts of California Commercial Investment Group v. Herrington, “even

On the facts of California Commercial Investment Group v. Herrington, “even

though the charges were dropped, [Defendant’s] statements made to police are protected as an exercise of the right to petition and of free speech.” The Fifth Court went on to find that no prima facie case was made on the plaintiff’s malicious-prosecution and defamation claims, and reversed the trial court’s denial of the defendant’s TCPA motion to dismiss. No. 05-19-00805-CV (July 8, 2020) (mem. op.).

The initials “JM” appeared on drawings ARCO (a consulting firm) prepared for products designed by Kendall Harter (an inventor and entrepreneur). The appellant in KBIDC Investments v. Zuru Toys, a case about the design of water-balloon devices, argued that Josh Malone worked for ARCO and was exposed to Harter’s ideas at ARCO, noting: “that the initials ‘JM’ appear on drawings ARCO prepared for other products designed by Harter, including drawings for a sandwich maker and a water-balloon gun. Appellant also points to Malone’s Linkedin.com profile, which states that his technical skills include ‘CAD,’ computer-aided design. Appellant also asserts, without citing any evidence other than Harter’s affidavit, that Malone’s house was ‘within a 30-minute drive of ARCO’s offices’ in Farmer’s Branch. Appellant also asserts that ARCO had no employees with the initials ‘JM’ at that time.” The Fifth Court saw this evidence differently, finding: “This evidence is too indefinite and uncertain to show Malone had access to Harter’s designs. It does not constitute circumstantial evidence that Malone worked at ARCO, that he had access to Harter’s provisional patent application or drawings, or that he misappropriated Harter’s trade secrets.” No. 05-19-00159-CV (June 26, 2020) (mem. op.) – and on rehearing (Oct. 9, 2020).

The initials “JM” appeared on drawings ARCO (a consulting firm) prepared for products designed by Kendall Harter (an inventor and entrepreneur). The appellant in KBIDC Investments v. Zuru Toys, a case about the design of water-balloon devices, argued that Josh Malone worked for ARCO and was exposed to Harter’s ideas at ARCO, noting: “that the initials ‘JM’ appear on drawings ARCO prepared for other products designed by Harter, including drawings for a sandwich maker and a water-balloon gun. Appellant also points to Malone’s Linkedin.com profile, which states that his technical skills include ‘CAD,’ computer-aided design. Appellant also asserts, without citing any evidence other than Harter’s affidavit, that Malone’s house was ‘within a 30-minute drive of ARCO’s offices’ in Farmer’s Branch. Appellant also asserts that ARCO had no employees with the initials ‘JM’ at that time.” The Fifth Court saw this evidence differently, finding: “This evidence is too indefinite and uncertain to show Malone had access to Harter’s designs. It does not constitute circumstantial evidence that Malone worked at ARCO, that he had access to Harter’s provisional patent application or drawings, or that he misappropriated Harter’s trade secrets.” No. 05-19-00159-CV (June 26, 2020) (mem. op.) – and on rehearing (Oct. 9, 2020).

The appellant in KBIDC Investments v. Zuru Toys contended that the appellees failed to segregate attorneys’-fee evidence among claims involving the Texas Theft Liability Act (compensable) and those for misappropriation of trade secrets and unfair competition (not compensable). The Fifth Court observed that a basic holding of Tony Gullo Motors v. Chapa, 212 S.W.3d 299 (Tex. 2006)–that “it is only when discrete legal services advance both a recoverable and unrecoverable claim that they are so intertwined that they need not be segregated”–was not overruled by Horizon Health Corp. v. Acadia Healthcare Co., 520 S.W.3d 848 (Tex. 2017), which as a factual matter found a failure to properly segregate fees related to a TTLA claim. Here, “[Appellees’] argument is that all of their attorney’s fees were reasonable and necessary to their prevailing on appellant’s TTLA claim. Their attorney testified to that fact. He also testified that the attorney’s fees would have been the same if the TTLA claim had been the only claim. Appellant does not identify any invoice entry that did not apply to the TTLA claim.” No. 05-19-00159-CV (June 26, 2020) (mem. op.).

The appellant in KBIDC Investments v. Zuru Toys contended that the appellees failed to segregate attorneys’-fee evidence among claims involving the Texas Theft Liability Act (compensable) and those for misappropriation of trade secrets and unfair competition (not compensable). The Fifth Court observed that a basic holding of Tony Gullo Motors v. Chapa, 212 S.W.3d 299 (Tex. 2006)–that “it is only when discrete legal services advance both a recoverable and unrecoverable claim that they are so intertwined that they need not be segregated”–was not overruled by Horizon Health Corp. v. Acadia Healthcare Co., 520 S.W.3d 848 (Tex. 2017), which as a factual matter found a failure to properly segregate fees related to a TTLA claim. Here, “[Appellees’] argument is that all of their attorney’s fees were reasonable and necessary to their prevailing on appellant’s TTLA claim. Their attorney testified to that fact. He also testified that the attorney’s fees would have been the same if the TTLA claim had been the only claim. Appellant does not identify any invoice entry that did not apply to the TTLA claim.” No. 05-19-00159-CV (June 26, 2020) (mem. op.).

“…the power granted by section 22.221(a) of the government code is not a power that is granted to prevent damage to the appellant pending appeal.’ ‘That purpose is served by the statutes allowing appellants to supersede judgments by posting an appropriate bond.’ Rather, the power to issue a writ of injunction is limited to the purpose of protecting appellate jurisdiction.

“…the power granted by section 22.221(a) of the government code is not a power that is granted to prevent damage to the appellant pending appeal.’ ‘That purpose is served by the statutes allowing appellants to supersede judgments by posting an appropriate bond.’ Rather, the power to issue a writ of injunction is limited to the purpose of protecting appellate jurisdiction.

Here, relators assert that the pending foreclosure threatens this Court’s jurisdiction over their existing appeal. But unlike the cases cited by relators involving appeals of interlocutory orders, the foreclosure of the property at issue does not moot their claims in the appeal and, thus, does not implicate the Court’s jurisdiction over the appeal.” In re Day Investment Group, No. 05-20-00643-CV (July 2, 2020) (mem. op.) (citation omitted, emphasis added).

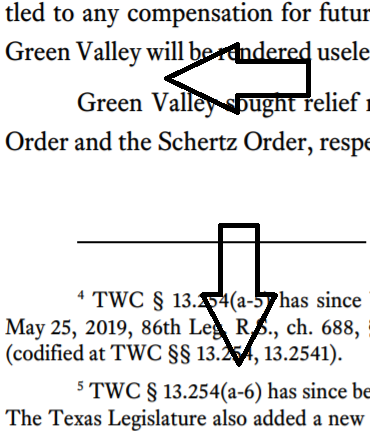

When not engaged in good-natured banter about typeface or proper spacing after periods, the appellate community often argues about the right place to put citations to authority. The traditional approach places them “inline,” along with the text of the legal argument. A contrarian viewpoint, primarily advanced by Bryan Garner, argues that citations should be placed in footnotes.

Has modern technology provided a third path? Professor Rory Ryan of Baylor Law School advocates “fadecites,” reasoning:

A brief using this approach would look like this on a first read:

(A longer example is available on Professor Ryan’s Google Drive.) The reader can quickly skim over citations while reviewing the legal argument. Additionally, assuming that the court’s technology allows it, case citations can be arranged to become more visible if the reader wants to know more information. Modern .pdf technology allows a citation to become darker and more visible if the reader places the cursor on it. A hyperlink to the cited authority could also be made available.

This idea offers an ingenious solution to a recurring challenge in writing good, accessible briefs. I’d be interested in your thoughts and Professor Ryan would be as well.

This is a crosspost from 600Hemphill, which follows business litigation in the Texas Supreme Court.

The Texas Supreme Court recently summarized the sometimes-confusing law about preservation of objections an an expert’s testimony:

The Texas Supreme Court recently summarized the sometimes-confusing law about preservation of objections an an expert’s testimony:

“Requiring an admissibility objection to the reliability of expert testimony gives the proponent a fair opportunity to cure any deficiencies and prevents trial and appeal by ambush. Thus, when an expert opinion ‘is admitted in evidence without objection, it may be considered probative evidence even if the basis of the opinion is unreliable.’ But conclusory or speculative opinion testimony is not relevant evidence because it does not make the existence of a material fact more or less probable. Evidence that lacks probative value will not support a jury finding even if admitted without objection. ‘Bare, baseless opinions will not support a judgment even if there is no objection to their admission in evidence.'”

Pike v. Texas EMC Management LLC, No. 17-0557 (June 19, 2020). While this quote eliminates the case citations in the original, the cited authorities provide further discussion of these principle and illustrate their applications in specific settings.

This is a crosspost from 600Hemphill, which follows business litigation in the Texas Supreme Court.

In Pike v. Texas EMC Mangagment LLC, ”‘Value’ was defined in the jury charge as ‘”Market Value,”’ the amount that would be paid in cash by a willing buyer who desires to buy, but is not required to buy, to a willing seller who desires to sell, but is under no necessity of selling.’”

Expert testimony sought to establish a $4.1 million value for the relevant plant and equipment, which the Texas Supreme Court rejected for three reasons:

Expert testimony sought to establish a $4.1 million value for the relevant plant and equipment, which the Texas Supreme Court rejected for three reasons:

“First, … [e]vidence of the purchase price of the Partnership’s property is insufficient under that measure because it does not establish the fair market value of the property at a different time.”

“Second, …[c]ourts employing an actual-value measure have held that ‘[f]rom that starting point, adjustments are made for wear and tear, depreciation, and other pertinent factors.’ Having examined the record, we disagree with the plaintiffs that [the expert] took anything other than purchase price—and a 20% escalation factor—into account in opining about the value of the plant and equipment.”

“Third, [the expert] did not attempt to tie the value of the plant to the market value of the

Partnership, which was the only measure of damages in the jury charge. He did not address whether any debt encumbered the plant, for example, or otherwise testify regarding how loss of the plant and equipment impacted the value of the Partnership as a whole.” (emphasis added, citations omitted)

The Court also rejected efforts to corroborate the expert’s testimony with lay-opinion testimony by an owner, because that testimony was based on book rather than actual value. Foreclosure-sale price was similarly irrelevant. No. 17-0557 (June 19, 2020).

In re Perl granted mandamus relief as to jurisdictional discovery requests.

In re Perl granted mandamus relief as to jurisdictional discovery requests.

As to scope, it reasoned (as to one set of the requests): “Interrogatory No. 2’s request for “details of how business is conducted between” Relators and Cake Craft, Interrogatory No. 8’s request for Relators’ “work, role and/or services” to Cake Craft, Request for Production No. 5’s requests for documents “regarding your engagement and business relationship” with Cake Craft, and Request for Production No. 15’s request for documents “that detail the inspecting and auditing services that you performed on the Cake Craft defendants” do not focus on any jurisdictional fact. None of these requests are confined to any of the three purposeful availment factors: Relators’ own activities, aimed at Texas, or the specific benefit, advantage, or profit Relators would earn from a Texas relationship.” (emphasis added)

As to adequate remedy, in response to the argument that “the only injury claimed is the ordinary expense of litigation,” the Court observed: “[A]llowing discovery of a potential claim against a defendant over which the court would not have personal jurisdiction denies him the protection Texas procedure would otherwise afford.” No. 05-20-00170-CV (June 2, 2020). LPHS represented the real parties in interest in this case.

On June 12, the Fifth Court revisited the ongoing litigation about Downtown Dallas’s much-reviled Confederate memorial, by granting the City’s emergency motion to put the memorial in “archival storage” in light of protests in the downtown area.

On June 12, the Fifth Court revisited the ongoing litigation about Downtown Dallas’s much-reviled Confederate memorial, by granting the City’s emergency motion to put the memorial in “archival storage” in light of protests in the downtown area.

Lunch-buying did not create arbitrator bias in Texas Health Management v. Healthspring: “THM next claims the Tribunal was partial because it received free beverages and meals from Healthspring every day of the hearing. THM claims it received this information from a Decem

Lunch-buying did not create arbitrator bias in Texas Health Management v. Healthspring: “THM next claims the Tribunal was partial because it received free beverages and meals from Healthspring every day of the hearing. THM claims it received this information from a Decem ber 5, 2017 letter from Healthspring to the Tribunal. However, on the first day of arbitration, Appel acknowledged, “I understand, Mr. Leckerman, you ordered in lunch.” Leckerman, Healthspring’s attorney, confirmed lunch would arrive around noon. THM did not question or object to Healthspring providing lunch.” (footnote omitted).

ber 5, 2017 letter from Healthspring to the Tribunal. However, on the first day of arbitration, Appel acknowledged, “I understand, Mr. Leckerman, you ordered in lunch.” Leckerman, Healthspring’s attorney, confirmed lunch would arrive around noon. THM did not question or object to Healthspring providing lunch.” (footnote omitted).

This is a cross-post from 600 Hemphill

It’s not a Texas Supreme Court case, but Title Source Inc. v. HouseCanary Inc. is a jury charge case worth reviewing. In it, the San Antonio Court of Appeals reversed a $700+ million judgment based in part on a classic Casteel issue. In reviewing the jury instruction about the plaintiff’s claim for theft of trade secrets, the Court observed:

It’s not a Texas Supreme Court case, but Title Source Inc. v. HouseCanary Inc. is a jury charge case worth reviewing. In it, the San Antonio Court of Appeals reversed a $700+ million judgment based in part on a classic Casteel issue. In reviewing the jury instruction about the plaintiff’s claim for theft of trade secrets, the Court observed:

“[T]he jury was also instructed that ‘improper means’ includes bribery, espionage, and ‘breach or inducement of a breach of a duty to maintain secrecy, to limit use, or to prohibit discovery of a trade secret.’ This instruction tracks TUTSA’s definition of ‘improper means’ and is therefore a correct statement of law. But HouseCanary conceded at oral argument that there is no evidence TSI acquired the trade secrets through bribery, and our review of the record reveals no evidence that TSI acquired the trade secrets through espionage. Because those theories are not supported by the evidence, they should have been omitted from the ‘improper means’ definition that was submitted to the jury.“

(emphasis added, citations omitted). The Court went on to cite Texas Supreme Court authority stating that while “a jury charge submitting liability under a statute should track the statutory language as closely as possible,” the statutory language “may be slightly altered to conform the issue to the evidence presented,” and that “[a] broad-form question cannot be used to put before the jury issues that have no basis in the law or the evidence.”

UDF v. Megatel illustrates the Fifth Court’s approach to “public concern” as defined by the TCPA: “[W]hile the alleged communications may have been motivated by a climate of public scrutiny created by criticisms of the UDF Parties’ business practices, the communications at issue did not in any way address the substance of either those criticisms or the resulting public scrutiny. Instead, they addressed only the termination of contracts . . . as a means for the UDF Parties to achieve liquidity which is not a matter ‘of political, social, or other concern to the community.'” No. 05-19-00647-CV (May 29, 2020) (mem. op.) (citation omitted).

The details of Duncan v. Park Place Motorcars provide a road map to “death penalty” sanctions, both substantively and procedurally as to the trial court’s findings: “On this record, we conclude the imposition of death penalty sanctions was just because it related directly to the conduct at issue in the case—specifically, Duncan’s failure to appear for the completion of his deposition, and generally, Duncan’s continuing violation of the trial court’s orders and hindrance of the discovery process for appellees; the trial court imposed lesser sanctions to no avail; and Duncan’s conduct throughout the long history of the case reasonably justified a presumption his affirmative claims lacked merit. Accordingly, we conclude the trial court did not abuse its discretion in ordering death penalty sanctions in this case.” No. 05-19-00032-CV (June 2, 2020) (mem. op.)

The details of Duncan v. Park Place Motorcars provide a road map to “death penalty” sanctions, both substantively and procedurally as to the trial court’s findings: “On this record, we conclude the imposition of death penalty sanctions was just because it related directly to the conduct at issue in the case—specifically, Duncan’s failure to appear for the completion of his deposition, and generally, Duncan’s continuing violation of the trial court’s orders and hindrance of the discovery process for appellees; the trial court imposed lesser sanctions to no avail; and Duncan’s conduct throughout the long history of the case reasonably justified a presumption his affirmative claims lacked merit. Accordingly, we conclude the trial court did not abuse its discretion in ordering death penalty sanctions in this case.” No. 05-19-00032-CV (June 2, 2020) (mem. op.)

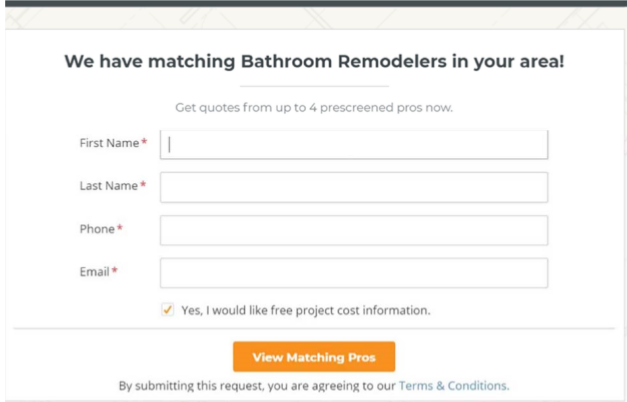

The philosophy of aesthetics finds practical application in the law of website user agreements, as illustrated in Home Advisor, Inc. v. Waddell. The plaintiffs sought to avoid arbitration of their claims, arguing that the notice about “terms and conditions” on this screen was not sufficiently conspicuous:

The Fifth Court disagreed. Citing the recent Northern District of Texas opinion in Phillips v. Neutron Holdings, the Court noted a distinction among “clickwrap” agreements, “browsewrap” agreements, and “sign-in-wrap” agreements. This case involved a sign-in wrap agreement, which “notifies the user of the existence of the website’s terms and conditions and advises the user that he or she is agreeing to the terms when registering an account or signing up,” and is “typically enforce[d] . . . when notice of the existence of the te rms was ‘reasonably conspicuous.'” The Court found that this agreement was conspicuous enough, noting that “more cluttered and complicated sign-in-wrap screens have been found to provide sufficient notice” of similar contract terms. No. 05-19-00669-CV (June 4, 2020) (mem. op.)

rms was ‘reasonably conspicuous.'” The Court found that this agreement was conspicuous enough, noting that “more cluttered and complicated sign-in-wrap screens have been found to provide sufficient notice” of similar contract terms. No. 05-19-00669-CV (June 4, 2020) (mem. op.)

“[W]e decline to extend the Supreme Court’s holding in Burnham to find personal jurisdiction over James in all of his capacities simply because he was served in his individual capacity while present in Texas. Such a holding would conflict with the consistent position taken by Texas courts that actions taken by an individual in a representative capacity are separate and distinct from actions taken in an individual’s personal capacity.” Hanschen v. Hanschen, No. 05-19-01134-CV (May 28, 2020) (mem. op.) A concurrence noted: “We did not conclude whether the trial court could obtain personal jurisdiction over James in his representative capacities in the future if he were to be served properly in those capacities.”

“[W]e decline to extend the Supreme Court’s holding in Burnham to find personal jurisdiction over James in all of his capacities simply because he was served in his individual capacity while present in Texas. Such a holding would conflict with the consistent position taken by Texas courts that actions taken by an individual in a representative capacity are separate and distinct from actions taken in an individual’s personal capacity.” Hanschen v. Hanschen, No. 05-19-01134-CV (May 28, 2020) (mem. op.) A concurrence noted: “We did not conclude whether the trial court could obtain personal jurisdiction over James in his representative capacities in the future if he were to be served properly in those capacities.”

Recent orders about conducting trials during the pandemic highlight the different procedural structures of the state and federal courts.

Recent orders about conducting trials during the pandemic highlight the different procedural structures of the state and federal courts.

In the state system, the Texas Supreme Court recently released its seventeenth emergency order about when and how jury trials may resume. (An order, incidentally, that I got from the txcourts.gov website, which shows progress in returning that site to normal after the recent hacker attack.)

In the federal system, the recent order in In re Tanner reminds of the considerable district court discretion about such matters: “[T]he district court has given great consideration to the COVID-19 issues addressed by Tanner. . . . [W]hatever each of us as judges might have done in the same circumstance is not the question. Instead, as cited below, the standards are much higher for evaluating the district court’s decision” for purposes of a writ of mandamus or prohibition. No. 20-10510 (May 29, 2020).

Here is the PowerPoint for my June 2 presentation to the DBA’s Appellate Law Section about Fifth Court commercial-litigation opinions over the last twelve months.

Here is the PowerPoint for my June 2 presentation to the DBA’s Appellate Law Section about Fifth Court commercial-litigation opinions over the last twelve months.

In a securities fraud case, a trial court issued a protective order against certain questioning of a nonparty deponent. After thoroughly reviewing Texas discovery law about relevance, a Fifth Court panel majority reversed:

In a securities fraud case, a trial court issued a protective order against certain questioning of a nonparty deponent. After thoroughly reviewing Texas discovery law about relevance, a Fifth Court panel majority reversed:

“[W]e conclude the two challenged lines of questioning were not necessarily outside the scope of relevant information. Information concerning other lawsuits is not per se outside the scope of discovery, and relators did not establish below that the circumstances of the non-party’s role in the Servergy and investment adviser situations are so dissimilar to the allegations here as to be irrelevant. Anything reasonably calculated to lead to the discovery of material evidence is generally within the scope of proper discovery.”

In re Cook, No. 05-19-01283-CV (May 20, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted). A dissent saw the matter differently:

“Here, relators have not clearly established that other discovery is unavailable to support their claims and defenses. In fact, the record is clear that the questions prohibited by the protective order were only ‘a few minutes of additional questions’ in a six-hour deposition, and relators were able to explore extensively the nonparty’s relationships with the parties and his familiarity with and participation in the events underlying the case.”

A helpful summary of the requirements for proving up a mandamus record appears in In re Gentry: “Documents become sworn copies when they are attached to an affidavit or to an unsworn declaration conforming to section 132.001 of the Texas Government Code. The affidavit or unsworn declaration must affirmatively show it is based on relator’s personal knowledge. The affidavit or unsworn declaration is insufficient unless the statements in it are direct and unequivocal and perjury can be assigned to them. An affidavit or unsworn declaration would comply with the rule if it stated, under penalty of perjury, that the affiant has personal knowledge that the copies of the documents in the appendix are true and correct copies of the originals.” No. 05-19-01283-CV (May 18, 2020) (mem. op.)

A helpful summary of the requirements for proving up a mandamus record appears in In re Gentry: “Documents become sworn copies when they are attached to an affidavit or to an unsworn declaration conforming to section 132.001 of the Texas Government Code. The affidavit or unsworn declaration must affirmatively show it is based on relator’s personal knowledge. The affidavit or unsworn declaration is insufficient unless the statements in it are direct and unequivocal and perjury can be assigned to them. An affidavit or unsworn declaration would comply with the rule if it stated, under penalty of perjury, that the affiant has personal knowledge that the copies of the documents in the appendix are true and correct copies of the originals.” No. 05-19-01283-CV (May 18, 2020) (mem. op.)

Pennington, Fields, and Phillips each owned 1/3 of the shares of Advantage Marketing & Labeling, Inc. Pennington argued that under their shareholder agreement he other two were required to buy his stock when he decided to sell his full interest and become a “retiring shareholder” under that agreement. Fields and Phillips resisted, pointing out that Pennington was employed by another business when he made his

Pennington, Fields, and Phillips each owned 1/3 of the shares of Advantage Marketing & Labeling, Inc. Pennington argued that under their shareholder agreement he other two were required to buy his stock when he decided to sell his full interest and become a “retiring shareholder” under that agreement. Fields and Phillips resisted, pointing out that Pennington was employed by another business when he made his  demand; thus, “because he was not ‘retired’ from any and all employment, he could not be a ‘retiring shareholder’ for purposes of the CPA.” The Fifth Court disagreed based on two basic contract-construction principles: “This construction . . . assigns a definition to only one of the two words the parties used to describe who must comply with the paragraph’s provisions. It also disregards the context. The paragraph imposes requirements for the disposition of shares by a ‘retiring shareholder’ in the context of an agreement that imposes restrictions on stock transfer.” Pennington v. Fields, No. 05-19-00149-CV (May 22, 2020) (mem. op.)

demand; thus, “because he was not ‘retired’ from any and all employment, he could not be a ‘retiring shareholder’ for purposes of the CPA.” The Fifth Court disagreed based on two basic contract-construction principles: “This construction . . . assigns a definition to only one of the two words the parties used to describe who must comply with the paragraph’s provisions. It also disregards the context. The paragraph imposes requirements for the disposition of shares by a ‘retiring shareholder’ in the context of an agreement that imposes restrictions on stock transfer.” Pennington v. Fields, No. 05-19-00149-CV (May 22, 2020) (mem. op.)

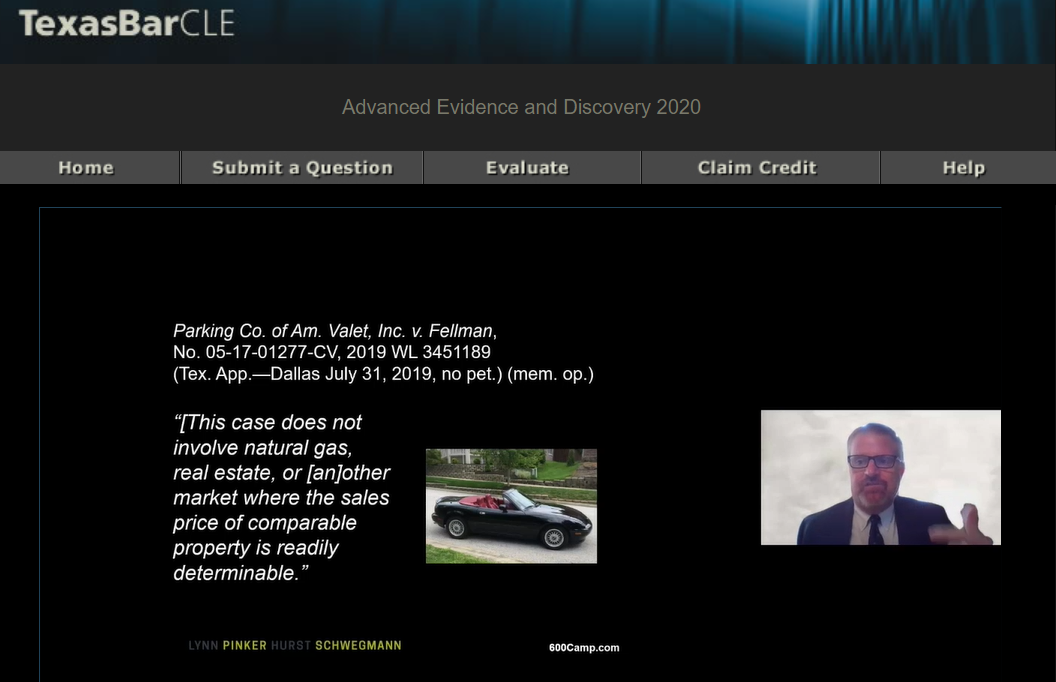

I spoke today, virtually, to the Texas Bar CLE’s 33rd “Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course,” which would have been in San Antonio. My topic was proving up damages in a commercial case, and I focused on ten specific issues identified in recent Texas and Fifth Circuit cases. I also showed off some smooth hand gestures, as you can see above. Here is a copy of my PowerPoint. The Bar staff did a terrific job with the A/V logistics and I look forward to doing another program with them soon.

I spoke today, virtually, to the Texas Bar CLE’s 33rd “Advanced Evidence and Discovery Course,” which would have been in San Antonio. My topic was proving up damages in a commercial case, and I focused on ten specific issues identified in recent Texas and Fifth Circuit cases. I also showed off some smooth hand gestures, as you can see above. Here is a copy of my PowerPoint. The Bar staff did a terrific job with the A/V logistics and I look forward to doing another program with them soon.

The tenants in a residential lease sued for injuries from toxic mold on the property. The Fifth Court expressed sympathy, but nevertheless affirmed summary judgment for the landlord based on an “as is” clause in the lease, citing Prudential Ins. Co. v. Jefferson Assocs. 896 S.W.2d 156 (Tex. 1995). In addition to noting that the clause was prominently written in all-caps, and consistent with other related provisions in the lease, the Court observed: ‘Before they entered into the Lease and related agreements, Rebecca walked through the house twice and Richard walked through the house once. After signing the Lease but prior to moving in, the Potters visited the house again and saw “black substance” on the wall and coming out of a wall socket. Rebecca testified she saw “bubbling” and “deforming” of a wall that, according to a workman, was caused by “clogged gutters.” In a subsequent visit prior to moving in, Richard saw “black underneath the carpet” being removed by a carpet repairman. When they were told by workmen the black substance was dirt and dog feces, the Potters did not further investigate.’ Potter v. HP Texas 1 LLC, No. No. 05-18-01513-CV (Apr. 6, 2019) (mem. op.)

The tenants in a residential lease sued for injuries from toxic mold on the property. The Fifth Court expressed sympathy, but nevertheless affirmed summary judgment for the landlord based on an “as is” clause in the lease, citing Prudential Ins. Co. v. Jefferson Assocs. 896 S.W.2d 156 (Tex. 1995). In addition to noting that the clause was prominently written in all-caps, and consistent with other related provisions in the lease, the Court observed: ‘Before they entered into the Lease and related agreements, Rebecca walked through the house twice and Richard walked through the house once. After signing the Lease but prior to moving in, the Potters visited the house again and saw “black substance” on the wall and coming out of a wall socket. Rebecca testified she saw “bubbling” and “deforming” of a wall that, according to a workman, was caused by “clogged gutters.” In a subsequent visit prior to moving in, Richard saw “black underneath the carpet” being removed by a carpet repairman. When they were told by workmen the black substance was dirt and dog feces, the Potters did not further investigate.’ Potter v. HP Texas 1 LLC, No. No. 05-18-01513-CV (Apr. 6, 2019) (mem. op.)

ACI, the general contractor on a hotel-construction project, was sued by Ram, the subcontractor who installed the window. Ram won a summary judgment for a violation of Texas’s Prompt Payment Act. ACI asserted a defense under the Construction Trust Fund Act involving “actual expenses directly related to the construction or repair of the improvement … .” The Fifth Court found the relevant statutory language clear and unambiguous, requiring no further use of statutory-interpretation techniques: “[The Trust Fund Act provision] acts as a defense to claims of misapplication of funds the contractor holds in trust for beneficiaries. It does not apply to a claim the contractor failed to promptly pay subcontractors.” Alberelli Constr. v. Ram Indus. Acquisitions LLC, No. 05-18-01529-CV (May 15, 2020).

ACI, the general contractor on a hotel-construction project, was sued by Ram, the subcontractor who installed the window. Ram won a summary judgment for a violation of Texas’s Prompt Payment Act. ACI asserted a defense under the Construction Trust Fund Act involving “actual expenses directly related to the construction or repair of the improvement … .” The Fifth Court found the relevant statutory language clear and unambiguous, requiring no further use of statutory-interpretation techniques: “[The Trust Fund Act provision] acts as a defense to claims of misapplication of funds the contractor holds in trust for beneficiaries. It does not apply to a claim the contractor failed to promptly pay subcontractors.” Alberelli Constr. v. Ram Indus. Acquisitions LLC, No. 05-18-01529-CV (May 15, 2020).

Appellant challenged a temporary injunction arising from a noncompetition agreement about supplying beauty products to salons. The Fifth Court affirmed in Kim v. Oh, holding, inter alia:

- Capacity. “Appellants argue the evidence in the record establishes they signed the contracts with Oh in their corporate, not individual, capacities, and consequently there are no enforceable contracts on which Oh can recover against appellants. Appellants further assert that Oh lacks capacity to recover in this suit, noting he signed the contracts as ‘Grace Beauty Supply’ and that Grace Beauty

Supply is not a party to this suit. However, these arguments raise affirmative defenses and dilatory pleas, which may be addressed at a later proceedings on the merits and are not issues to be resolved at this stage . . . ” (footnote omitted).

Supply is not a party to this suit. However, these arguments raise affirmative defenses and dilatory pleas, which may be addressed at a later proceedings on the merits and are not issues to be resolved at this stage . . . ” (footnote omitted). - Irreparable Injury. This testimony worked: “Oh stated there had been many violations of the noncompetition provisions, but he could not estimate how many because there were ‘too many’ to count. He saw appellants at his customers’ salons ‘many times’ after they terminated their contracts with him in December 2018. He believed appellants were competing with him for the same business and would continue to violate the noncompetition provisions. Oh testified it had been ‘very, very difficult’ for him to rebuild his customer base and that he was expecting a ‘difficult time’ when asked if he would be able to survive financially in the months between the hearing and the trial.” No. 05-19-00947-CV (May 11, 2020) (mem. op.)

Discovery problems led to a contempt finding and an order imposing jail time in In re Duncan, No. 05-19-01572-CV (May 14, 2020) (mem. op.) The Fifth Court granted habeas relief, noting this basic due-process requirement in this area:

Discovery problems led to a contempt finding and an order imposing jail time in In re Duncan, No. 05-19-01572-CV (May 14, 2020) (mem. op.) The Fifth Court granted habeas relief, noting this basic due-process requirement in this area:

“Contempt may be. . .divided into civil or coercive contempt, which involves confinement pending obedience to the trial court’s order, and criminal or punitive contempt, which results in a punishment for past transgressions. In cases where the trial court seeks to impose criminal or punitive constructive contempt, due process requires a contemnor to either be present or affirmatively waive his or her presence for the contempt hearing.. When the contemnor fails to appear for the contempt hearing, the trial court must issue a capias or writ of attachment to secure the contemnor’s presence.”

(emphasis added, citations omitted, applying, inter alia, In re Reece, 341 S.W.3d 360 (Tex. 2011), and Ex parte Alloju, 907 S.W.2d 486 (Tex. 1995)).

The Fifth Court’s newly-released opinions are back online, with opinions accessible on a website and a new Twitter account. A press release from the Court has additional information about access while the main txcourts.gov site continues to be down. Bloggers and court observers rejoice!

The Fifth Court’s newly-released opinions are back online, with opinions accessible on a website and a new Twitter account. A press release from the Court has additional information about access while the main txcourts.gov site continues to be down. Bloggers and court observers rejoice!

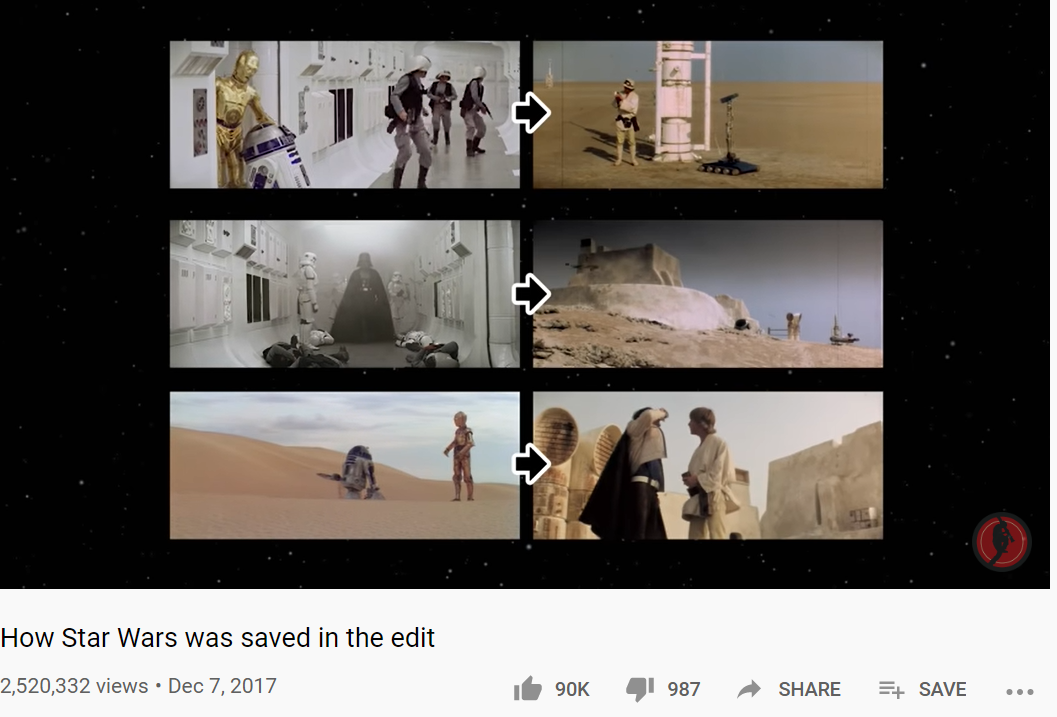

With the kids home from school because of the coronavirus, I’ve watched a lot of YouTube videos over their shoulders. In particular, this one tells the fascinating story about how post-production editing saved Star Wars, which was bloated and impossible to follow in its first rough versions. Among

With the kids home from school because of the coronavirus, I’ve watched a lot of YouTube videos over their shoulders. In particular, this one tells the fascinating story about how post-production editing saved Star Wars, which was bloated and impossible to follow in its first rough versions. Among  other changes, the start of the film was drastically simplified – from a series of back-and-forths between space and Tatooine, to a focus on the opening space battle and no shots of Tatooine until the droids landed there. This bit of editing is directly relevant to the tendency of legal writers to “define” (introduce) all characters and terms at the beginning of their work, without regard to the flow of the narrative that follows.

other changes, the start of the film was drastically simplified – from a series of back-and-forths between space and Tatooine, to a focus on the opening space battle and no shots of Tatooine until the droids landed there. This bit of editing is directly relevant to the tendency of legal writers to “define” (introduce) all characters and terms at the beginning of their work, without regard to the flow of the narrative that follows.

It is hard to blog about the Texas state appellate courts when their website has been the victim of a ransomware attack! The unfortunate incident has been well-covered by the Texas Lawbook and Law360. Posts on this blog will be less frequent until the situation is resolved.

It is hard to blog about the Texas state appellate courts when their website has been the victim of a ransomware attack! The unfortunate incident has been well-covered by the Texas Lawbook and Law360. Posts on this blog will be less frequent until the situation is resolved.

A trademark-user who establishes prior use of the mark can still lose his rights to it if he abandoned them. “A party trying to show abandonment must prove that the owner of the mark both discontinued use of it and that he did not intend to resume its use in the reasonably foreseeable future. Nonuse of a mark for a period of three consecutive years creates a rebuttable presumption that a mark has been abandoned without intent to resume its use.” (citation omitted).

A trademark-user who establishes prior use of the mark can still lose his rights to it if he abandoned them. “A party trying to show abandonment must prove that the owner of the mark both discontinued use of it and that he did not intend to resume its use in the reasonably foreseeable future. Nonuse of a mark for a period of three consecutive years creates a rebuttable presumption that a mark has been abandoned without intent to resume its use.” (citation omitted).

In King Aerospace, Inc. v. King Aviation Dallas, the appellee contended that the relevant mark was abandoned after the appellant had a serious accident. “KAC contends it made a prima facie case of abandonment because Randall admitted he did not make any aircraft sales from 1993 until at least 2000. Although Randall testified he did not personally sell any aircraft while he was recovering from his near-fatal accident, he also  testified his father, Sam, was conducting the business of the company during that time. Jordan testified that, while Randall was recovering, he helped Sam file monthly reports identifying what airplanes they owned, when they bought them, and when they sold them.” This evidence established use and defeated the intent requirement: “The fact that Sam continued the business of the company, and Randall resumed selling planes using the names King Aviation and King Aviation Dallas as soon as he was able to do so, is evidence of his intent to resume use of the marks.” No. 05-19-00245-CV (April 30, 2020) (mem. op.).

testified his father, Sam, was conducting the business of the company during that time. Jordan testified that, while Randall was recovering, he helped Sam file monthly reports identifying what airplanes they owned, when they bought them, and when they sold them.” This evidence established use and defeated the intent requirement: “The fact that Sam continued the business of the company, and Randall resumed selling planes using the names King Aviation and King Aviation Dallas as soon as he was able to do so, is evidence of his intent to resume use of the marks.” No. 05-19-00245-CV (April 30, 2020) (mem. op.).

To the right, Pikachu is waving, but the appellee in King Aerospace, Inc. v. King Aviation Dallas was not waiving, as the Fifth Court observed:

To the right, Pikachu is waving, but the appellee in King Aerospace, Inc. v. King Aviation Dallas was not waiving, as the Fifth Court observed:

In its reply brief, KAC contends Randall’s responsive brief on appeal, filed pro se, “provides nothing for this Court to review” because it fails to cite to the appellate record or legal authority. In his response, Randall informed the Court he was unable to find appellate counsel and he submitted his trial counsel’s post-trial brief as his response to KAC’s appellate arguments. KAC, as the appellant, has the burden to show grounds for reversal on appeal. Randall, as appellee, was not required to file a brief for us to review what was presented to the trial court; thus, he cannot be said to have committed “waiver” due to inadequate briefing.

No. 05-19-00245-CV (April 30, 2020) (mem. op.) (citation omitted, emphasis added).

On pages 62-63 of the May 2020 issue of “D CEO” magazine, you can read a profile of me as the only Tarot-reading lawyer in Dallas–a skill first acquired on trips to New Orleans for appellate business!

On pages 62-63 of the May 2020 issue of “D CEO” magazine, you can read a profile of me as the only Tarot-reading lawyer in Dallas–a skill first acquired on trips to New Orleans for appellate business!

The Fifth Court’s recent opinion in Guillory v. Dietrich addressed the appropriate subjects for findings of fact. The Court continued discussion of that subject in King Aerospace, Inc. v. King Aviation Dallas, a rare state-court trademark-infringement case. (The substantive holdings of King will be discussed in later posts.) The Court rejected the appellants’ arguments that these additional findings of fact should have been made:

The Fifth Court’s recent opinion in Guillory v. Dietrich addressed the appropriate subjects for findings of fact. The Court continued discussion of that subject in King Aerospace, Inc. v. King Aviation Dallas, a rare state-court trademark-infringement case. (The substantive holdings of King will be discussed in later posts.) The Court rejected the appellants’ arguments that these additional findings of fact should have been made:

- A finding about the “tacking” doctrine about a trademark’s use, when that doctrine was not necessary to support the trial court’s judgment, as well as a similar unnecessary finding about the effect of the Appellee’s bankruptcy;

- “Although the trial court made no specific finding regarding the date [Appellee] began using the . . . mark, it concluded Appellee had prior common law rights in that mark” (emphasis added);

- Appellant objected that the findings “fail to specify how [Appellee] used the marks in commerce and the effect of [his] inability to work after his accident,” as to which the Court found: “The trial court found that [Appellee] continuously used the . . . marks and neither abandoned them nor intended to abandon them. These findings sufficiently address the controlling issues and are all that is required.”

No. 05-19-00245-CV (April 30, 2020) (mem. op.).