“First Ovilla sought to build a house on property that is encumbered by restrictive covenants, and the property owners’ association had previously sought to prevent another builder from constructing a house with a similar building plan. The amended permanent injunction signed in that case (and on which appellees largely relied in their plea to the jurisdiction) has been dissolved by this Court. Therefore, given the record before us, the declarations sought by First Ovilla present a justiciable controversy and are not moot.” First Ovila v. Primm, No. 05-19-00042-CV (April 27, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

The jury charge in an attorney-client fee dispute asked: “Did any of the following persons form an agreement with Glast, Phillips & Murray, PC to pay for fees concerning legal representation?” The question then required the jury to answer “yes” or “no” for both of the defendants on that claim. They lost, and argued on appeal that “question one asked the jury if a contract had been formed between the parties—an issue the [defendants] argue was not in dispute—but neglected to ask whether the agreement was for payment of a flat fee or GPM’s hourly rates” (citing Lone Starr Multi-Theatres v. Max Interests, 365 S.W.3d 688 (Tex. App.–Houston [1st Dist.] 2011, no pet.)

The jury charge in an attorney-client fee dispute asked: “Did any of the following persons form an agreement with Glast, Phillips & Murray, PC to pay for fees concerning legal representation?” The question then required the jury to answer “yes” or “no” for both of the defendants on that claim. They lost, and argued on appeal that “question one asked the jury if a contract had been formed between the parties—an issue the [defendants] argue was not in dispute—but neglected to ask whether the agreement was for payment of a flat fee or GPM’s hourly rates” (citing Lone Starr Multi-Theatres v. Max Interests, 365 S.W.3d 688 (Tex. App.–Houston [1st Dist.] 2011, no pet.)

The Fifth Court found no abuse of discretion in the submission. It distinguished Lone Starr, a landlord-tenant dispute, as involving a disconnect between the jury’s damages finding and the judgment, in that “none of the questions submitted to the jury asked the amount of lost rentals suffered by the landlord, and the [jury’s] ‘fair market value’ determination did not include or even support a lost rentals determination.” Here, in contrast: “. . . in answering question four, the jury calculated GPM’s damages as the amount of GPM’s outstanding invoices, an amount derived from GPM’s hourly rates and billable hours rather than any flat fee. Accordingly, the jury necessarily rejected the Namdars’ capped fee term, and the answer to question four informs us that the jury determined the parties agreed that the Namdars would pay GPM’s hourly rates for the hours billed.” Narmarkhan v. Glast Phillips & Murray, No. 18-0802-CV (April 24, 2020) (mem. op.).

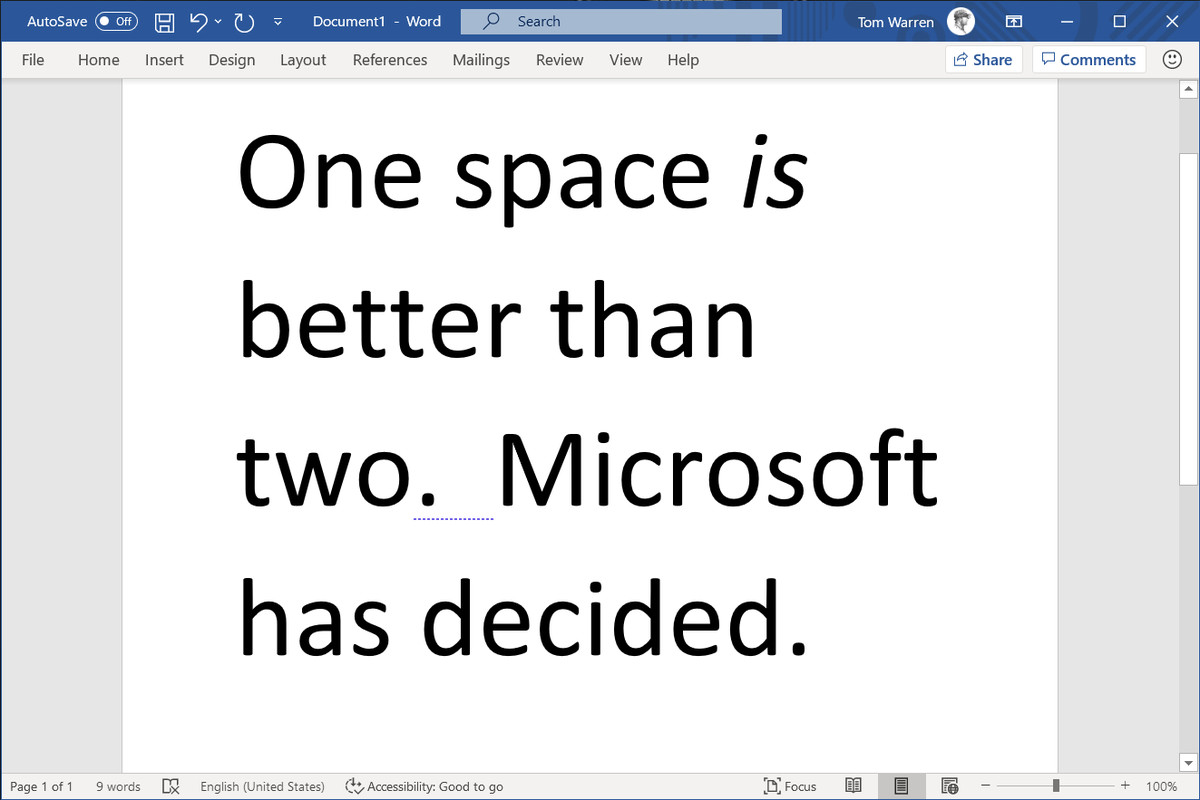

As reported by The Verge on April 24, Microsoft Word now auto-corrects the use of two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence. The battle, such as it was, should now be considered over. This influential article in Slate explains why the one-spacers – while correct during the era of typewriters, which made every letter and space the same size – have been wrong since the early 1990s and the widespread availability of proportional spacing in modern word processing software.

As reported by The Verge on April 24, Microsoft Word now auto-corrects the use of two spaces after a period at the end of a sentence. The battle, such as it was, should now be considered over. This influential article in Slate explains why the one-spacers – while correct during the era of typewriters, which made every letter and space the same size – have been wrong since the early 1990s and the widespread availability of proportional spacing in modern word processing software.

Evans v. Martinez arose from a jury trial as to whether reasonable diligence had been used in serving a defendant, against whom suit had been filed on the last day of the limitations period. The jury answered “no” and the Fifth Court affirmed the resulting judgment: “Here, the return of service recites that the process server first came into possession of the citation on October 27, 2015, more than a month after limitations expired. Although Weinkauf offered some evidence regarding the delay, he did not explain why, when he knew he had filed suit on the last day of limitations and that he would shortly leave on vacation, he did not make an alternative arrangement to ensure that the effort to serve Martinez would begin in his absence. On his return, he left the citation sitting at his reception desk and checked on it only once a week even after problems arose with his arrangements for service. There is no evidence to support his testimony of the efforts he made, such as phone records, notes, emails, or testimony from support staff or process servers.” No. 05-18-01241-CV (April 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

Evans v. Martinez arose from a jury trial as to whether reasonable diligence had been used in serving a defendant, against whom suit had been filed on the last day of the limitations period. The jury answered “no” and the Fifth Court affirmed the resulting judgment: “Here, the return of service recites that the process server first came into possession of the citation on October 27, 2015, more than a month after limitations expired. Although Weinkauf offered some evidence regarding the delay, he did not explain why, when he knew he had filed suit on the last day of limitations and that he would shortly leave on vacation, he did not make an alternative arrangement to ensure that the effort to serve Martinez would begin in his absence. On his return, he left the citation sitting at his reception desk and checked on it only once a week even after problems arose with his arrangements for service. There is no evidence to support his testimony of the efforts he made, such as phone records, notes, emails, or testimony from support staff or process servers.” No. 05-18-01241-CV (April 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

Amend v. J.C. Penney Corp. declined to apply the TCPA to a noncompete case. As to the right of association the Court observed: ‘Amend testified he is “responsible for Lowe’s’ website and app sales,” “responsible for online merchandising,” and responsible for “driving sales.” In his position, he works with others on “product management,” “analytics,” “digital technology,” and “strategy and business development,” and he makes recommendations to other Lowe’s employees about these subjects. The evidence does not show that these responsibilities necessarily involve public communications. Instead the responsibilities appear to involve communications between Amend and other Lowe’s employees.’ No. 05-19-00723 (March 31, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added) (LPHS represented the successful appellee in this case.)

“'[A] plaintiff’s failure to have a valid [assumed name] certificate on file is not a jurisdictional issue but, rather, a capacity issue that is properly raised in a plea in abatement so that the cause may be suspended while the defect is corrected.’ By failing to file a verified plea in abatement prior to trial, appellees waived their complaint.” Pennington v. Cypress Aviation, No. 05-19-00345-CV (April 9, 2020) (mem. op.); cf. Malouf v. Sterquell PSF Settlement LC, No. 05-17-01343-CV (Nov. 7, 2019, pet. filed) (mem. op.) (finding no waiver when the plaintiffs’ “claimed status as a . . . partner was a primary focus of both sides’ arguments at trial”).

“'[A] plaintiff’s failure to have a valid [assumed name] certificate on file is not a jurisdictional issue but, rather, a capacity issue that is properly raised in a plea in abatement so that the cause may be suspended while the defect is corrected.’ By failing to file a verified plea in abatement prior to trial, appellees waived their complaint.” Pennington v. Cypress Aviation, No. 05-19-00345-CV (April 9, 2020) (mem. op.); cf. Malouf v. Sterquell PSF Settlement LC, No. 05-17-01343-CV (Nov. 7, 2019, pet. filed) (mem. op.) (finding no waiver when the plaintiffs’ “claimed status as a . . . partner was a primary focus of both sides’ arguments at trial”).

Barnes sued Kinser; in response, Kinser moved for sanctions. Barnes then moved to dismiss the sanctions request under the TCPA. The Fifth Court, citing a series of opinions involving analogous filings, held: “The request for sanctions here, like the similar request in Misko, is not a request for legal or equitable relief and not a legal action as defined by the TCPA.” Barnes v. Kinser, No. 05-19-00481-CV (April 7, 2020).

Barnes sued Kinser; in response, Kinser moved for sanctions. Barnes then moved to dismiss the sanctions request under the TCPA. The Fifth Court, citing a series of opinions involving analogous filings, held: “The request for sanctions here, like the similar request in Misko, is not a request for legal or equitable relief and not a legal action as defined by the TCPA.” Barnes v. Kinser, No. 05-19-00481-CV (April 7, 2020).

Alcala sought to avoid arbitration of a premises-liability claim against her employer, arguing, inter alia, that she did not understand English. Her argument did not prevail because of direct-benefits estoppel:

Alcala sought to avoid arbitration of a premises-liability claim against her employer, arguing, inter alia, that she did not understand English. Her argument did not prevail because of direct-benefits estoppel:

‘The record reflects Alcala received $5,116.46 under the Plan in the form of benefits paid to cover medical expenses related to the subject of her suit against appellants: her February 2016 on-the-job injury. The Plan itself provided, “there is an Arbitration Policy attached to the back of this booklet.” The Agreement provided, “Payments made under [the] Plan . . . constitute consideration for this Agreement.” Having obtained the benefits under the Plan, which incorporates the Agreement by reference, Alcala cannot legally or equitably object to the arbitration provision in the Agreement.’

Multipacking Solutions v. Alcala, No. 05-19-00303-CV (April 14, 2020).

Resolving an unclear area about Sabine Pilot claims for wrongful discharge, the Fifth Court held in “Sandberg did not plead or present evidence that ST[Microelectonics] ever required him to sign false tax statements or other financial documents. Instead, the gist of his claim is that he was terminated for stating he would not execute the documents ‘if there was a breach of the [Advanced Pricing Agreement] agreement and improper adjusting entries were included in the accounting figures’. Sandberg’s pleading does not allege facts showing ST forced Sandberg “to choose between illegal activity and [his] livelihood[].” Sandberg v. STMicroelectronics, Inc., No. 05-18-01360-CV (April 9, 2020).

Sabine Pilot claims for wrongful discharge, the Fifth Court held in “Sandberg did not plead or present evidence that ST[Microelectonics] ever required him to sign false tax statements or other financial documents. Instead, the gist of his claim is that he was terminated for stating he would not execute the documents ‘if there was a breach of the [Advanced Pricing Agreement] agreement and improper adjusting entries were included in the accounting figures’. Sandberg’s pleading does not allege facts showing ST forced Sandberg “to choose between illegal activity and [his] livelihood[].” Sandberg v. STMicroelectronics, Inc., No. 05-18-01360-CV (April 9, 2020).

Associate judges play a valuable role in helping cases move along. The relevant statute sets limits, however, as illustrated by Kam v. Kam, No. No. 05-19-01293-CV (April 10, 2020) (mem. op.): “The final judgment here was signed by the associate judge but not the judge of the referring court. While the associate judge may have decided all issues and the parties may have agreed to appeal directly to this Court, the judgment is not appealable until the judge of the referring court has signed it. SeeTex. Gov’t Code §§ 54A.214(b), 54A.217(b). . . . Accordingly, we lack jurisdiction and dismiss the appeal and any pending motions.”

Associate judges play a valuable role in helping cases move along. The relevant statute sets limits, however, as illustrated by Kam v. Kam, No. No. 05-19-01293-CV (April 10, 2020) (mem. op.): “The final judgment here was signed by the associate judge but not the judge of the referring court. While the associate judge may have decided all issues and the parties may have agreed to appeal directly to this Court, the judgment is not appealable until the judge of the referring court has signed it. SeeTex. Gov’t Code §§ 54A.214(b), 54A.217(b). . . . Accordingly, we lack jurisdiction and dismiss the appeal and any pending motions.”

This is a cross-post from 600 Hemphill which follows the Texas Supreme Court.

This is a cross-post from 600 Hemphill which follows the Texas Supreme Court.

B.C. v. Steak & Shake, the supreme court reversed a Dallas case case that declined to consider a late-filed summary judgment submission, holding: “We . . . conclude that the trial court’s recital that it considered the ‘evidence and arguments of counsel,’ without any limitation, is an ‘affirmative indication’ that the trial court considered B.C.’s response and the evidence attached to it. The court of appeals concluded this reference ‘indicates nothing more than the trial court considered [Steak N Shake’s evidence] in conjunction with the traditional motion.’ But a court’s recital that it generally considered ‘evidence’—especially when one party objected to the timeliness of all of the opposing party’s evidence—overcomes the presumption that the court did not consider it.” No. 17-1008 (March 27, 2020) (per curiam)

After a jury trial, Mumford was declared to be a sexually violent predator and then civilly committed. Dr. Turner, a psychologist, interviewed him and prepared a written report. The trial court struck, for procedural reasons, another expert who the State planned to call at trial, and then allowed the State to offer Dr. Turner’s written report in evidence. The Fifth Court reversed, finding that the report was prepared in anticipation of litigation (the commitment proceedings) and thus was not admissible as a business record. As to harm, it said: “Dr. Turner’s report was the only evidence that appellant ‘suffers from a behavioral abnormality that makes the person likely to engage in a predatory act of sexual violence.’ Without evidence to support that finding, the jury could not have found

After a jury trial, Mumford was declared to be a sexually violent predator and then civilly committed. Dr. Turner, a psychologist, interviewed him and prepared a written report. The trial court struck, for procedural reasons, another expert who the State planned to call at trial, and then allowed the State to offer Dr. Turner’s written report in evidence. The Fifth Court reversed, finding that the report was prepared in anticipation of litigation (the commitment proceedings) and thus was not admissible as a business record. As to harm, it said: “Dr. Turner’s report was the only evidence that appellant ‘suffers from a behavioral abnormality that makes the person likely to engage in a predatory act of sexual violence.’ Without evidence to support that finding, the jury could not have found

appellant was a sexually violent predator.” In re Mumford, No. 05-19-00186-CV (March 31, 2020) (mem. op.)

The Fifth Court’s website reports: “The Fifth District Court of Appeals at Dallas has set up a YouTube channel for live streaming oral arguments held via Zoom Web Conferencing. The channel is online and open for subscriptions.”

The Fifth Court’s website reports: “The Fifth District Court of Appeals at Dallas has set up a YouTube channel for live streaming oral arguments held via Zoom Web Conferencing. The channel is online and open for subscriptions.”

The channel is available here and is a wonderful addition to public awareness and knowledge about this Court.

Ali v. DSA Partners provides a useful reminder about a common situation in multi-party litigation: “[A]s a general rule, severance after an interlocutory summary-judgment order to expedite appellate review is proper and not an abuse of discretion.” No. 05-18-01240-CV (March 24, 2020) (mem. op.).

Ali v. DSA Partners provides a useful reminder about a common situation in multi-party litigation: “[A]s a general rule, severance after an interlocutory summary-judgment order to expedite appellate review is proper and not an abuse of discretion.” No. 05-18-01240-CV (March 24, 2020) (mem. op.).

The appellants in Trubenbach v. Energy Exploration “urge[d] that ‘context matters.’ They argue that as non-signatories, they can compel Energy Exploration to arbitration but Energy Exploration cannot compel them to arbitration. But this is not a case in which non-signatories first moved to compel arbitration, then later changed their minds, withdrew their consent, and proceeded with the litigation in a judicial forum. Here, appellants urged diametrically opposing positions in two different courts at the same time.” (emphasis in original).

The appellants in Trubenbach v. Energy Exploration “urge[d] that ‘context matters.’ They argue that as non-signatories, they can compel Energy Exploration to arbitration but Energy Exploration cannot compel them to arbitration. But this is not a case in which non-signatories first moved to compel arbitration, then later changed their minds, withdrew their consent, and proceeded with the litigation in a judicial forum. Here, appellants urged diametrically opposing positions in two different courts at the same time.” (emphasis in original).

As a result, “[t]heir conduct in claiming rights under the arbitration agreement and their conduct throughout the course of this proceeding clearly reflected their willingness to forego their right to a judicial forum.” No. 05-18-01090-CV (March 27, 2020) (mem. op.). The Court also observed: “Appellants’ actions are akin to behavior prohibited by the invited error doctrine—a party may not complain of an error which the party invited.” (citations omitted).

The business fallout from the failed bus-camera program at the now-defunct Dallas County Schools (“DCS”) led to litigation about the related intellectual property, which led to a TCPA motion filed by a bidder on the technology during the winding up of DCS. The Fifth Court found that the (pre-September-2019) TCPA did not apply, emphasizing its free-speech prong but also finding no protected right of association or petition:

The business fallout from the failed bus-camera program at the now-defunct Dallas County Schools (“DCS”) led to litigation about the related intellectual property, which led to a TCPA motion filed by a bidder on the technology during the winding up of DCS. The Fifth Court found that the (pre-September-2019) TCPA did not apply, emphasizing its free-speech prong but also finding no protected right of association or petition:

Although the BusStop Technology provides safety measures for children who ride school buses, the benefits of the technology were not the basis of the communications. ATS’s communications with DCS and the Dissolution Committee, including requesting and receiving information about the technology, obtaining prototypes of the technology, and ATS’s actual bid, were private communications about a private, commercial transaction. Similarly, although DCS and the Dissolution Committee are governmental entities, the transactions and associated communications were private financial transactions that did not impact the public; the transactions did not require public approval, and ATS did not argue that the governmental status of DCS and the Dissolution Committee brought the communications into the realm of public concern.

BusPatrol America LLC v. American Traffic Solutions, Inc., No. 05-18-00920-CV (March 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

The key issue in Hernandez v. Sun Crane & Hoist, Inc. was whether a general contractor exercised “actual control” over a subcontractor’s work. The en banc court reversed a no-evidence summary judgment for the contractor, observing in footnote 9:

“. . . The original panel’s analysis omits any mention of (1) the Subcontract provisions described above regarding schedule control and mandatory safety harness use; (2) Johnston’s testimony that JLB supervisory employees were on-site on the day of the accident and knew the cage could fall over in the event of strong wind or improper bracing; (3) Hernandez’s testimony that he saw JLB supervisors looking at the cage’s bracing prior to the accident; and (4) Molina’s statements that the wind speed was 15–25 miles per hour on the day of the accident and Hernandez was told to jump, but was tethered to the cage by his safety harness.

Those omissions demonstrate that the original panel’s opinion represents a serious departure from precedent in the review of no-evidence summary judgment cases and therefore warrants en banc review under Texas Rule of Appellate Procedure 41.2 to ‘secure or maintain uniformity of the court’s decisions.'”

The court split cleanly along party lines, with all Democratic justices joining the majority opinion, and all Republican justices joining two dissents. Justice Bridges disagreed with the majority’s legal analysis while Justice Whitehill questioned whether the case had warranted en banc consideration. No. 05-17-00719-CV (March 26, 2020).

The estate of Billy Dickson alleged that he died from asbestos exposure at a Bell Helicopter plant. The estate won at trial on a theory of gross negligence. The panel reversed on legal sufficiency grounds, finding no evidence that Bell subjectively knew of a risk to Dickson based on his use of boards containing asbestos as part of the testing of helicopter components. Bell Helicopter Textron v. Dickson, No. 05-17-00979-CV (Aug. 23, 2019) (mem. op.) Justice Bridges wrote the opinion, joined by Justice Whitehill and then-Justice Brown.

The full court denied en banc review on March 25. Justice Bridges signed the order, apparently joined by Justices Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, Pedersen, and Evans. Justices Molberg and Nowell did not participate.

The full court denied en banc review on March 25. Justice Bridges signed the order, apparently joined by Justices Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, Pedersen, and Evans. Justices Molberg and Nowell did not participate.

A dissent criticized the panel’s application of the City of Keller standard as not properly considering all the evidence heard by the jury, and noted : “This court has misapplied the legal sufficiency standard of review to second-guess jury verdicts before and here, it does so again.” Justice Carlyle wrote the opinion, joined by Chief Justice Burns and Justices Osborne, Partida-Kipness, and Reichek.

A concurrence, written by Justice Whitehill and joined by all other Republican Justices on the Court (Justices Bridges, Myers, Schenck, and Evans), responded to the dissent, noting inter alia: “With no apparent bearing on the correct legal analysis of the issues in this case, the dissenting opinion (i) criticizes four prior opinions from this Court that are not asbestos cases and have no apparent logical relationship to this case . . . ”

A concurrence, written by Justice Whitehill and joined by all other Republican Justices on the Court (Justices Bridges, Myers, Schenck, and Evans), responded to the dissent, noting inter alia: “With no apparent bearing on the correct legal analysis of the issues in this case, the dissenting opinion (i) criticizes four prior opinions from this Court that are not asbestos cases and have no apparent logical relationship to this case . . . ”

To summarize, the vote was 6-5 against en banc review, largely on party lines, and would have come out differently had the two nonparticipating Justices joined their Democratic colleagues.

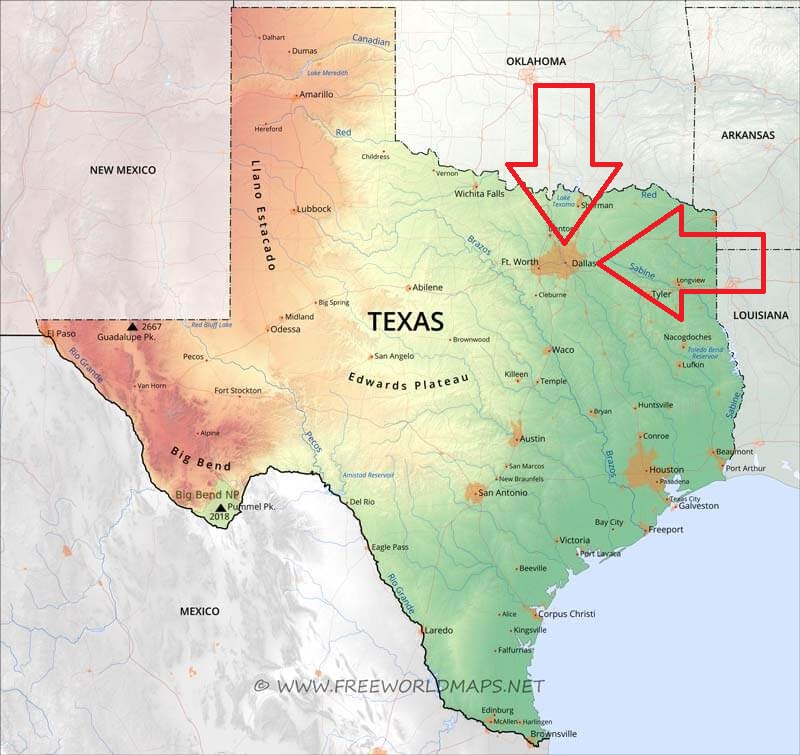

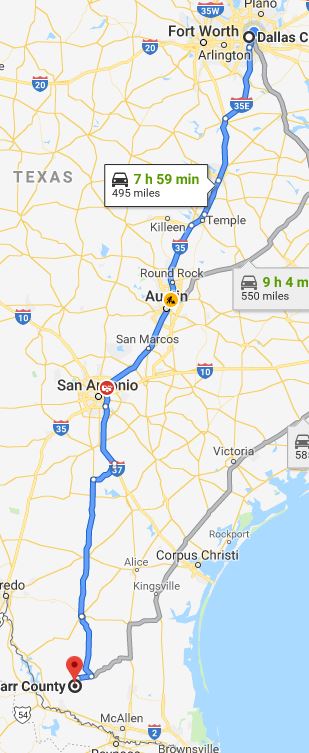

The coronavirus situation has prompted review of once-obscure statutes and rules; among them, Tex. R. App. 17, which addresses where to go if the ordinarily-assigned court of appeals is unavailable. Surprisingly, Rule 17.2 sends the relevant party to the nearest alternative court of appeals, measured by distance from the trial court. For courts in the Dallas district, then, that could be Fort Worth, Waco, Tyler, or Texarkana. (To be clear, THE DALLAS COURT IS AVAILABLE, this post is just a note on a TRAP that has become less obscure in light of current events.)

The coronavirus situation has prompted review of once-obscure statutes and rules; among them, Tex. R. App. 17, which addresses where to go if the ordinarily-assigned court of appeals is unavailable. Surprisingly, Rule 17.2 sends the relevant party to the nearest alternative court of appeals, measured by distance from the trial court. For courts in the Dallas district, then, that could be Fort Worth, Waco, Tyler, or Texarkana. (To be clear, THE DALLAS COURT IS AVAILABLE, this post is just a note on a TRAP that has become less obscure in light of current events.)

While mandamus litigation often focuses on whether a clear abuse of discretion occurred, the other relevant factors can also be dispositive. Consider the panel majority in In re Alpha-Barnes Real Estate Services LLC, which observed: “While the trial court’s order presents an error potentially justifying reversal on a direct appeal, has failed to demonstrate the inadequacy of an appeal, particularly given the limited scope of the order and alternative mechanisms by which relator may introduce the same evidence excluded by the order.” It also relied upon laches, noting a lengthy and unexplained delay in seeking mandamus relief. A dissent would have granted the petition, noting the likely effect on the trial, and that the parties had entered a stipulation about the otherwise-unexplained delay. No. 05-20-00073-CV (March 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

While mandamus litigation often focuses on whether a clear abuse of discretion occurred, the other relevant factors can also be dispositive. Consider the panel majority in In re Alpha-Barnes Real Estate Services LLC, which observed: “While the trial court’s order presents an error potentially justifying reversal on a direct appeal, has failed to demonstrate the inadequacy of an appeal, particularly given the limited scope of the order and alternative mechanisms by which relator may introduce the same evidence excluded by the order.” It also relied upon laches, noting a lengthy and unexplained delay in seeking mandamus relief. A dissent would have granted the petition, noting the likely effect on the trial, and that the parties had entered a stipulation about the otherwise-unexplained delay. No. 05-20-00073-CV (March 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

One Dallas Court of Appeals case addresses the breach-of-contract defense of impracticability, Hewitt v Biscaro, 353 S.W.3d 304 (Tex. App.—Dallas 2011, no pet.). Relevant to the current crisis, it involves a government order that allegedly made performance more difficult. The Court examined whether:

- the performance issue was a basic assumption of the contract;

- the government’s action was an official order or regulation (in that case, the SEC’s contact with the defendant was not); and

- the defendant was acting in good faith.

The Court relied on an earlier Texas Supreme Court case and the relevant Restatement (Second) of Contracts provision. Application of this opinion will be important in upcoming commercial disputes created by the novel coronavirus.

This is a cross-post from 600Hemphill, which follows the Texas Supreme Court:

This is a cross-post from 600Hemphill, which follows the Texas Supreme Court:

Henry McCall lived in a cabin on Homer Hillis’s property, occasionally helping Hillis with maintenance at the McCall’s bed-and-breakfast. While working on Hillis’s sink, a brown recluse spider bit McCall. The Texas Supreme Court found that the ferae naturae doctrine barred McCall’s lawsuit against  Hillis: “[H]e owed no duty to the invitee because he was unaware of the presence of brown recluse spiders on his property and he neither attracted the offending spider to his property nor reduced it to his possession. Further, [McCall] had actual knowledge of the presence of spiders on the property.” Hillis v. McCall, No. 18-1065 (Tex. March 13, 2020). In addition to its impact on brown-recluse litigation, the reasoning of this opinion about liability for small, dangerous creatures well be relevant in any future litigation about coronavirus exposure.

Hillis: “[H]e owed no duty to the invitee because he was unaware of the presence of brown recluse spiders on his property and he neither attracted the offending spider to his property nor reduced it to his possession. Further, [McCall] had actual knowledge of the presence of spiders on the property.” Hillis v. McCall, No. 18-1065 (Tex. March 13, 2020). In addition to its impact on brown-recluse litigation, the reasoning of this opinion about liability for small, dangerous creatures well be relevant in any future litigation about coronavirus exposure.

In re Johnson catches the eye as an atypical non-memorandum opinion in a pro se mandamus proceeding arising from a criminal case. The novel feature of the opinion is its footnote (longer than the actual opinion), using the Court’s “discretion to take judicial notice of adjudicative facts that are matters of public record” to review the relevant online docket sheet to establish mootness. No. 05-20-00068-CV (March 11, 2020)

In re Johnson catches the eye as an atypical non-memorandum opinion in a pro se mandamus proceeding arising from a criminal case. The novel feature of the opinion is its footnote (longer than the actual opinion), using the Court’s “discretion to take judicial notice of adjudicative facts that are matters of public record” to review the relevant online docket sheet to establish mootness. No. 05-20-00068-CV (March 11, 2020)

The trial court dismissed Heri Automotive’s counterclaims for forum non conveniens. Heri appealed. The Fifth Court dismissed because “no authority exists authorizing the appeal of the challenged interlocutory order,” and also noted that “appellant cites no authpority, and we have found none, that authorizes mandamus review of an interlocutory order granting a motion to dismiss for forum non conveniens.” Heri Automotive v. Adams, No. 05-19-01215-CV (Feb. 21, 2020) (mem. op.).

The trial court dismissed Heri Automotive’s counterclaims for forum non conveniens. Heri appealed. The Fifth Court dismissed because “no authority exists authorizing the appeal of the challenged interlocutory order,” and also noted that “appellant cites no authpority, and we have found none, that authorizes mandamus review of an interlocutory order granting a motion to dismiss for forum non conveniens.” Heri Automotive v. Adams, No. 05-19-01215-CV (Feb. 21, 2020) (mem. op.).

A 2018 article with an LPCH colleague considered when it is wise for an intermediate appellate court, subject to further review by the Texas Supreme Court, to take issues en banc. That article has been updated on this page on this website to reflect the supreme court’s recent Flakes opinion; only time will tell whether the recent rulings and dissents by the en banc Dallas court will draw supreme court interest.

After the 2018 election, an LPCH colleague and I wrote about the potential for renewed interest in “factual sufficiency” review–closely related to “legal sufficiency” review, but placed in the exclusive jurisdiction of the intermediate courts of appeal under the state constitution.

After the 2018 election, an LPCH colleague and I wrote about the potential for renewed interest in “factual sufficiency” review–closely related to “legal sufficiency” review, but placed in the exclusive jurisdiction of the intermediate courts of appeal under the state constitution.

An example appeared in In re C.V.L., where a panel majority reversed the termination of a parent-child relationship in a factual sufficiency review: “[E]vidence that Father used m ethamphetamines twice during the underlying proceedings and Bonds’ unsubstantiated belief that Father will use drugs again in the future because he used drugs twice in the past is not enough under a factual sufficiency review to permanently deprive Father and child of a relationship when weighed against all of the contrary, uncontroverted evidence presented at trial and the strong presumption that a child’s best interests are served by maintaining the parent–child relationship.”

ethamphetamines twice during the underlying proceedings and Bonds’ unsubstantiated belief that Father will use drugs again in the future because he used drugs twice in the past is not enough under a factual sufficiency review to permanently deprive Father and child of a relationship when weighed against all of the contrary, uncontroverted evidence presented at trial and the strong presumption that a child’s best interests are served by maintaining the parent–child relationship.”

A dissent saw the court of appeals’ role differently: “This case presents important questions regarding an appellate court’s ability to second guess a factfinder’s pivotal credibility determinations in a termination case given the supreme court’s admonition that despite the heightened standard of review in termination cases, courts of appeals must nevertheless still provide due deference to the factfinder’s credibility determinations.” No. 05-19-00506-CV (Dec. 13, 2019, pet. filed) (mem. op.)

Factual sufficiency review in this type of family-law case involves unique issues that may not arise in commercial disputes, but the case is still an important example of how this standard works in practice.

In a dispute about arbitrability, the plaintiff claimed never to have seen the arbitration agreement, and after receiving evidence about the defendant’s computer system, the trial judge agreed.

In a dispute about arbitrability, the plaintiff claimed never to have seen the arbitration agreement, and after receiving evidence about the defendant’s computer system, the trial judge agreed.

A panel majority affirmed the denial of the motion to compel arbitration: “Aerotek made the choice to forego in-person wet-ink signatures on paper contracts. This may be a good business decision that allows it to more efficiently process more business than otherwise possible. And in this case, Aerotek made the choice to bring only one person, an employee without apparent IT experience specific to the type of computer system whose technical reliability and security she sought to vouch for. Aerotek did this in the face of admitting it had contracted out creation and implementation of this system to another entity altogether and brought no witness from that entity. We conclude Aerotek did not present evidence establishing the opposite of a vital fact, here that appellees’ denials of ever seeing the a rbitration contracts were physically impossible given Aerotek’s computer system.”

rbitration contracts were physically impossible given Aerotek’s computer system.”

A dissent had a different view of the evidence and warned that as a policy matter: “This would allow any party to a contract signed electronically to deny the existence of the contract even in the face of overwhelming evidence that the contract was signed. Further, this holding amounts to a state rule discriminating on its face against arbitration, which is expressly prohibited.”

The en banc court denied review in a brief order (Justices Molberg (the trial judge) and Whitehill did not participate); a dissent by Justice Schenck reiterated the dissent’s warnings and “urge[d] prompt review by the Texas Supreme Court.” (joined by Justices Bridges (the panel dissenter), Evans, and Myers).

In the 2018 election for a Dallas County Justice of the Peace position, Democratic candidate Margaret O’Brien obtained a default judgment that her Republican opponent, Ashley Hutcheson, was ineligible for the position because of her residence. IAfter the  election, in December 2018, a Fifth Court panel reversed, finding that the order was void because an Election Code provision bars default judgments in election cases, and further finding that the matter was not moot and required a further trial-court order because the judgment included an award of attorneys’ fees.

election, in December 2018, a Fifth Court panel reversed, finding that the order was void because an Election Code provision bars default judgments in election cases, and further finding that the matter was not moot and required a further trial-court order because the judgment included an award of attorneys’ fees.

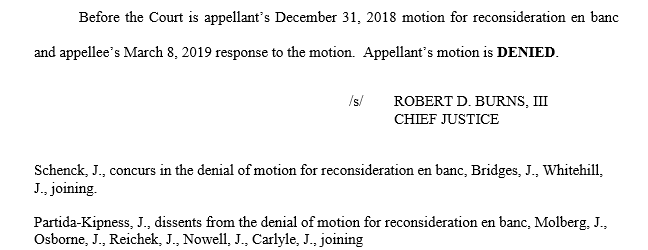

Litigation continued before the en banc court (the makeup of which significantly changed in the same 2018 election), which ultimately settled. In a short opinion by Chief Justice Burns on March 6, 2020, a majority of the Court dismissed the case as moot and withdrew the panel opinion.

Controversy ensued, as reflected by the four other opinions issued that day:

Controversy ensued, as reflected by the four other opinions issued that day:

- A dissent by Justice Schenck found that the matter was not moot (as it was capable

of repetition, etc.), agreed with the reasoning of the panel, and criticized the decision to withdraw the panel’s opinion (joined by Justices Bridges and Evans); - Another dissent, by Justice Whitehill, criticized the decision to withdraw the panel’s opinon for other reasons (also joined by Justice Bridges);

- A concurrence and dissent by Justice Bridges (the author of the panel opinion) agreed with the conclusion that the case is moot, disagreed with the withdrawal of the panel opinion, and reiterated the reasoning of that opinion (joined by Justices Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, and Evans — the full complement of Republican Justices on the present court);

- A concurrence by Justice Molberg clashed with the substantive reasoning of the dissents, but concluded that the order was void for another reason – ripeness – as the election had not yet occurred at the time of judgment. This opinion was joined by all other Democratic Justices on the court except Justice Pedersen, who did not participate in the case.

Liederman, a New York lawyer, sent seventy-seven emails to Texas, made five phone calls there, and signed and delivered three tolling agreements to Davis, a Texas-based attorney, “over a span of three years in working towards settling appellees’ claims.” The Fifth Court found no specific personal jurisdiction, observing: “Liederman could have ‘quite literally’ interacted with Davis, who could have been anywhere in the world, in the same manner. . . . It is apparent that Invasix’s contacts with Davis were based on her representation of the nonresident plaintiffs in the personal injury lawsuit and had nothing to do with the State of Texas.” Invasix, Inc. v. James, No. 05-19-00494-CV (Feb. 25, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added). The Court also found no general personal jurisdiction, applying recent Texas and United States Supreme Court opinions that have limited the scope of that doctrine.

Liederman, a New York lawyer, sent seventy-seven emails to Texas, made five phone calls there, and signed and delivered three tolling agreements to Davis, a Texas-based attorney, “over a span of three years in working towards settling appellees’ claims.” The Fifth Court found no specific personal jurisdiction, observing: “Liederman could have ‘quite literally’ interacted with Davis, who could have been anywhere in the world, in the same manner. . . . It is apparent that Invasix’s contacts with Davis were based on her representation of the nonresident plaintiffs in the personal injury lawsuit and had nothing to do with the State of Texas.” Invasix, Inc. v. James, No. 05-19-00494-CV (Feb. 25, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added). The Court also found no general personal jurisdiction, applying recent Texas and United States Supreme Court opinions that have limited the scope of that doctrine.

In Grisaffi v. Rocky Mountain High Brands, the Fifth Court reversed and remanded a default judgment after identifying an impermissible double recovery on the key issue: “Although Grisaffi committed numerous wrongful acts against Rocky Mountain, the default judgment awards Rocky Mountain $3.5 million as compensation for ‘funds obtained through fraud, breach of fiduciary duty and conversion with respect to Series A Preferred Stock . . . .’ The default judgment further awards Rocky Mountain declaratory relief to void the issuance of that Series A Preferred Stock. Thus, both the monetary and declaratory relief awarded to Rocky Mountain compensate it for the single injury of the wrongful issuance of Series A Preferred Stock caused by Grisaffi.” No. 05-18-01020-CV (Feb. 27, 2020) (mem. op.)

In Grisaffi v. Rocky Mountain High Brands, the Fifth Court reversed and remanded a default judgment after identifying an impermissible double recovery on the key issue: “Although Grisaffi committed numerous wrongful acts against Rocky Mountain, the default judgment awards Rocky Mountain $3.5 million as compensation for ‘funds obtained through fraud, breach of fiduciary duty and conversion with respect to Series A Preferred Stock . . . .’ The default judgment further awards Rocky Mountain declaratory relief to void the issuance of that Series A Preferred Stock. Thus, both the monetary and declaratory relief awarded to Rocky Mountain compensate it for the single injury of the wrongful issuance of Series A Preferred Stock caused by Grisaffi.” No. 05-18-01020-CV (Feb. 27, 2020) (mem. op.)

Section 171.025 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code says: “The court shall stay a proceeding that involves an issue subject to arbitration if an order for arbitration or an application for that order is made under this subchapter.” The dispute in In re: Baby Dolls Topless Saloon involved a mandamus petition from a defendant’s perceived inability to obtain an order implementing this stay, during its interlocutory appeal from denial of its motion to compel arbitration.

Section 171.025 of the Civil Practice & Remedies Code says: “The court shall stay a proceeding that involves an issue subject to arbitration if an order for arbitration or an application for that order is made under this subchapter.” The dispute in In re: Baby Dolls Topless Saloon involved a mandamus petition from a defendant’s perceived inability to obtain an order implementing this stay, during its interlocutory appeal from denial of its motion to compel arbitration.

The panel majority denied the petition, finding that the issue of arbitrability “has been briefed in the interlocutory appeal and will be decided by the panel of justices assigned to decide that appeal, which is just as the legislature intended when it enacted section 51.016 and provided for an interlocutory appeal of an order denying a motion to compel arbitration. Because we follow the rule of law, we, as one panel of this Court, will not depart from this Court’s prior holding that mandamus will not issue when the legislature has expressly provided an adequate remedy by appeal.”

A dissent would have granted a stay as part of resolution of the mandamus petition, noting: “While our own statute and rules appear to compel the same result by dictating a stay of the overlapping proceedings of whatever court is first asked, we have not done so here. Accordingly, relator has properly brought the issue before us for mandamus relief that should be available under long recognized mandamus standards and without the need of further machination or a fifth request for stay.” No. 05-20-00015-CV (Feb. 24, 2020) (mem. op.)

In re Catapult Realty arose from a foreclosure that wound a complex path through the Dallas courthouse, and offers two practice reminders about such situations:

In re Catapult Realty arose from a foreclosure that wound a complex path through the Dallas courthouse, and offers two practice reminders about such situations:

- The judge of one district court signed a TRO on behalf of another district judge. The resulting order was void because “[t]he record does not reflect that another temporary injunction or other evidentiary hearing was held before the 298th district judge prior to her signing the 2nd TRO.”;

- A county court granted a plea in abatement based on her perceived inability to decide subject-matter jurisdiction. Mandamus relief was proper when this decision was incorrect legally, and where the resulting order “does not specify the circumstances that will allow for the case to be reinstated,” thus denying the plaintiff “the right to proceed to a resolution of the forcible-detainer action within a reasonable time.”

Nos. 05-19-01056-CV & -00109-CV (Feb. 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

“Birds of a feather flock together,” says the old proverb. But on the Fifth Court, justices of the same political party do not always rule together, as shown by two recent opinions.

“Birds of a feather flock together,” says the old proverb. But on the Fifth Court, justices of the same political party do not always rule together, as shown by two recent opinions.

The first, Inland Western v. Nguyen, No. 05-17-00151-CV (Feb. 10, 2020) began when the owners of a nail salon, the Nguyens, sued their landlord for alleged misrepresentations about lease renewal. They won a judgment in their favor after a jury trial, after which a Fifth Court panel reversed and rendered judgment for the landlord.

The Nguyens petitioned for rehearing en banc. The court granted their petition, held oral argument and then reversed course Feb. 10 in a 10-4 decision. It issued a short, form order denying en banc reconsideration without discussing the merits.

The order was supported by all five of the current Republican justices (David Bridges, Lana Myers, Bill Whitehill, David Schenck and David Evans), joined by retired Justice Robert Fillmore from the original panel. Four of the Democratic justices (Leslie Osborne, Bill Pedersen, Amanda Reichek and Cory Carlyle) also joined the order.

Three of those Republican justices joined Inland Western v. Nguyen inland concurrence that emphasized the judicial oversight of jury trials: “[Our system, like the federal, recognizes … that there is no right to a judgment on a jury verdict if the legal theory is invalid or the objective quality of the evidence does not support the jury’s finding.” Justice Schenck wrote the concurring opinion, joined by justices Bridges and Evans.

A four-justice dissent was joined by four other Democratic justices. Chief Justice Robert Burns wrote that he would remand for a new trial, noting, “Appellate courts are duty bound to indulge every reasonable inference to sustain a jury verdict when the evidence supports the verdict.” He was joined by justices Ken Molberg, Robbie Partida-Kipness and Erin Nowell.

The Nguyen opinions show the importance of party affiliation, in that all Republicans on the court joined the decision to deny review, while all the dissenting justices were Democrats. But at the same time, Nguyen reminds that the new Democratic majority on the Dallas court is not a monolithic block, as four of those justices joined the majority while four dissented.

The second case, In re: Parks, No. 05-19-00375-CV (Feb. 18, 2020) (mem. op.), denied a mandamus petition about a trial court order striking counteraffidavits related to the reasonableness and necessity of certain medical expenses filed under Chapter 18 of the Civil Practice and Remedies Code.

The second case, In re: Parks, No. 05-19-00375-CV (Feb. 18, 2020) (mem. op.), denied a mandamus petition about a trial court order striking counteraffidavits related to the reasonableness and necessity of certain medical expenses filed under Chapter 18 of the Civil Practice and Remedies Code.

Republican Justice Bridges, joined by Democratic Justice Carlyle, drew an analogy between the trial court’s ruling and an order striking expert-witness designations, which is not ordinarily a basis for mandamus relief.

Republican Justice Schenck—who wrote the Nguyen concurrence—dissented, arguing that the present state of Dallas law “raises serious constitutional concerns related to the parties’ rights to a trial by jury, as well as their due process rights….” While from the same party as Justice Bridges, the two differed on an important procedural point about the balance of power between trial and appellate judges.

Going forward, these two cases are a good reminder that party affiliation, while important, is far from dispositive as to how a particular justice may approach a case.

(A similar article appeared this week in the Texas Lawbook. My LPCH partner Jason Dennis represents the Nguyens.)

By early 2019, the attorney-client relationship between Klein and McCray was disintegrating. With a summary judgment hearing looming, Klein moved for continuance and asked for latitude at the hearing “because my client has not provided me with key materials” and discussing the topic of his withdrawal. The trial court then granted summary judgment against McCray (in an order that Klein agreed to “as to form”), after which Klein moved for withdrawal and was allowed to do so.

By early 2019, the attorney-client relationship between Klein and McCray was disintegrating. With a summary judgment hearing looming, Klein moved for continuance and asked for latitude at the hearing “because my client has not provided me with key materials” and discussing the topic of his withdrawal. The trial court then granted summary judgment against McCray (in an order that Klein agreed to “as to form”), after which Klein moved for withdrawal and was allowed to do so.

McCray sought relief from the judgment, “denying he received notice of the summary judgment motion from Klein.” This request led to a difficult, but outcome-determinative question, as to whether Klein’s knowledge should be imputed to McCray, despite their deteriorated relationship:

If [McCray] is correct in his position on the law and facts, then Craddock applies to his claim because it means he would have had no notice of the motion, the failure to respond, or the summary judgment hearing, and a motion for new trial is the proper method to challenge the summary judgment. If he is incorrect on his no-imputation argument, then Carpenter applies and he is required to challenge the trial court’s denial of his motion for continuance for an abuse of discretion, which he has not done.

The Fifth Court held that “[b]ecause Klein was still actively (if not sufficiently) representing [McCray] prior to and at the summary judgment hearing, Klein’s knowledge is imputed to [McCray].” McCray v. McCray, No. 05-19-00556-CV (Feb. 20, 2020).

The Committee for a Qualified Judiciary has published its list of local judicial candidates found qualified.

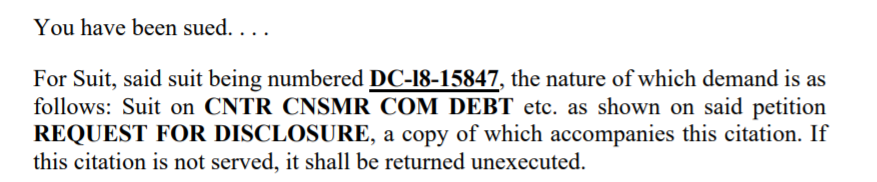

Bad service was found, and a restricted appeal succeeded, in Plummer v. Enterra Capital when the citation described the documents served (without attachments) as:

and otherwise: “The E&P citation was to be served on Plummer as E&P’s registered agent on Ridgeview Drive in Richardson, but handwriting next to the printed address showed an address on Arapaho Road in Richardson for a different entity, Richmond Engineering, Inc. Both of the returns show service at the Arapaho Road address. The Officer’s Return on each citation showed service on November 16, 2018, but the blank following ‘by delivering to the within named’ was not filled in on either return.” No. 05-19-00255-CV (Feb. 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

and otherwise: “The E&P citation was to be served on Plummer as E&P’s registered agent on Ridgeview Drive in Richardson, but handwriting next to the printed address showed an address on Arapaho Road in Richardson for a different entity, Richmond Engineering, Inc. Both of the returns show service at the Arapaho Road address. The Officer’s Return on each citation showed service on November 16, 2018, but the blank following ‘by delivering to the within named’ was not filled in on either return.” No. 05-19-00255-CV (Feb. 20, 2020) (mem. op.)

In re Parks denied a mandamus petition arising from the striking of counteraffidavits, related to the reasonableness and necessity of certain medical expenses, filed pursuant to Chapter 18 of the Civil Practice and Remedies Code. Applying Fifth Court precedent, the Court drew an analogy to the striking

In re Parks denied a mandamus petition arising from the striking of counteraffidavits, related to the reasonableness and necessity of certain medical expenses, filed pursuant to Chapter 18 of the Civil Practice and Remedies Code. Applying Fifth Court precedent, the Court drew an analogy to the striking  of expert designations, which is not ordinarily addressed by mandamus review. A dissenting opinion argued that “our existing construction raises serious constitutional concerns related to the parties’ rights to a trial by jury, as well as their due process rights to a decision on the merits and to appellate review,” and would have considered the merits of the petition. No. 05-19-00375-CV (Feb. 18, 2020) (mem. op.)

of expert designations, which is not ordinarily addressed by mandamus review. A dissenting opinion argued that “our existing construction raises serious constitutional concerns related to the parties’ rights to a trial by jury, as well as their due process rights to a decision on the merits and to appellate review,” and would have considered the merits of the petition. No. 05-19-00375-CV (Feb. 18, 2020) (mem. op.)

Morales v. Barnes reminds how an appellate mandate should guide further trial-court proceedings: “Our December 29, 2017 judgment and related mandate, however, rendered a partial judgment dismissing only Barnes’ claims based on the second letter. We affirmed the trial court’s denial of the motion to dismiss Barnes’ claims based on the first letter and we remanded those claims to the trial court for further proceedings. We conclude that by dismissing any claims based on the first letter, the trial court’s order was inconsistent with and failed to give full effect to our December 29, 2017 judgment and related mandate.” No. 05-18-00767-CV (Feb. 7, 2020) (mem. op.)

Morales v. Barnes reminds how an appellate mandate should guide further trial-court proceedings: “Our December 29, 2017 judgment and related mandate, however, rendered a partial judgment dismissing only Barnes’ claims based on the second letter. We affirmed the trial court’s denial of the motion to dismiss Barnes’ claims based on the first letter and we remanded those claims to the trial court for further proceedings. We conclude that by dismissing any claims based on the first letter, the trial court’s order was inconsistent with and failed to give full effect to our December 29, 2017 judgment and related mandate.” No. 05-18-00767-CV (Feb. 7, 2020) (mem. op.)

Jones v. Schachar succinctly summarizes compliance with Malooly: “The appellant can do this by either asserting a separate issue challenging each possible ground, or asserting a general issue that the trial court erred in granting summary judgment and within that issue providing argument negating all possible grounds upon which summary judgment could have been granted.” No. 05-19-00188-CV (Feb. 11, 2020) (mem. op.)

Jones v. Schachar succinctly summarizes compliance with Malooly: “The appellant can do this by either asserting a separate issue challenging each possible ground, or asserting a general issue that the trial court erred in granting summary judgment and within that issue providing argument negating all possible grounds upon which summary judgment could have been granted.” No. 05-19-00188-CV (Feb. 11, 2020) (mem. op.)

The Nguyens, owners of a nail salon, sued their landlord for alleged misrepresentations related to lease renewal. They won a judgment in their favor after a jury trial; a Fifth Court panel reversed and rendered judgment for the landlord. The Court granted the Nguyens’ motion for en banc rehearing, which produced these three points of view after oral argument:

The Nguyens, owners of a nail salon, sued their landlord for alleged misrepresentations related to lease renewal. They won a judgment in their favor after a jury trial; a Fifth Court panel reversed and rendered judgment for the landlord. The Court granted the Nguyens’ motion for en banc rehearing, which produced these three points of view after oral argument:

- A majority of justices denied the request for en banc review in a short, one-line order (Justices Bridges, Myers, Whitehill, Schenck, Osborne, Pedersen, Reichek, Carlyle, Evans, and from the original panel, Justice Fillmore).

A short concurrence underscored the importance of a judge’s power to set aside a jury verdict when required by law (Justice Schenck, joined by Justices Bridges and Evans) (as all three concurring Justices are named “David,” one

A short concurrence underscored the importance of a judge’s power to set aside a jury verdict when required by law (Justice Schenck, joined by Justices Bridges and Evans) (as all three concurring Justices are named “David,” one  could say they viewed the case in “3-D”)

could say they viewed the case in “3-D”)- Four justices dissented, emphasizing the importance of jury deliberations to the civil justice system (Chief Justice Burns, joined by Justices Molberg, Partida-Kipness, and Nowell).

No. 05-17-00151-CV (Feb. 10, 2020) (My LPCH partner Jason Dennis represented the Nguyens.)

An in-house lawyer for Ruhrpumpen, Inc., a company involved in substantial patent litigation, claimed an interest in the contingent fee agreement of the company’s outside counsel. The Fifth Court rejected the claim, holding: “[W]e conclude that a company’s general counsel owes the company a fiduciary duty not to accept compensation from anyone other than the company for working on a case for the company or for referring the case to a law firm without disclosing that compensation to the company and getting the company’s consent. In this case, Moore did not have authority to consent on Ruhrpumpen’s behalf to the fee-sharing agreement unless he had disclosed the agreement to the management of Ruhrpumpen other than himself.The record establishes that Moore did not disclose the fee-sharing agreement to Ruhrpumpen’s managers. Therefore, Moore did not have authority to consent to the fee-sharing agreement on Ruhrpumpen’s behalf.” Cokinos, Bosien & Young v. Moore, No. 05-18-01340-CV (Feb. 4, 2020) (mem op.)

An in-house lawyer for Ruhrpumpen, Inc., a company involved in substantial patent litigation, claimed an interest in the contingent fee agreement of the company’s outside counsel. The Fifth Court rejected the claim, holding: “[W]e conclude that a company’s general counsel owes the company a fiduciary duty not to accept compensation from anyone other than the company for working on a case for the company or for referring the case to a law firm without disclosing that compensation to the company and getting the company’s consent. In this case, Moore did not have authority to consent on Ruhrpumpen’s behalf to the fee-sharing agreement unless he had disclosed the agreement to the management of Ruhrpumpen other than himself.The record establishes that Moore did not disclose the fee-sharing agreement to Ruhrpumpen’s managers. Therefore, Moore did not have authority to consent to the fee-sharing agreement on Ruhrpumpen’s behalf.” Cokinos, Bosien & Young v. Moore, No. 05-18-01340-CV (Feb. 4, 2020) (mem op.)

“The contract, which neither side contends is ambiguous, bears Mr. Turnbow’s signature and does not mention PMC Chase or indicate representative capacity in any way. Thus, on its face, the contract unambiguously shows it is the obligation of Mr.Turnbow personally.” Accordingly, among other reasons, judgment against Mr. Turnbow was affirmed. PMC Chase, LLP v. Branch Structural Solutions, Inc., No. 05-18-01383-CV (Jan. 28, 2020) (mem. op.).

“The contract, which neither side contends is ambiguous, bears Mr. Turnbow’s signature and does not mention PMC Chase or indicate representative capacity in any way. Thus, on its face, the contract unambiguously shows it is the obligation of Mr.Turnbow personally.” Accordingly, among other reasons, judgment against Mr. Turnbow was affirmed. PMC Chase, LLP v. Branch Structural Solutions, Inc., No. 05-18-01383-CV (Jan. 28, 2020) (mem. op.).

Last Friday’s opinion by the Texas Supreme Court in St. John Missionary Baptist Church v. Flakes reversed St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church v. Flakes, 547 S.W.3d 311 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2018) (en banc). The law of appellate briefing waiver now has (at least) these features:

Last Friday’s opinion by the Texas Supreme Court in St. John Missionary Baptist Church v. Flakes reversed St. John’s Missionary Baptist Church v. Flakes, 547 S.W.3d 311 (Tex. App.–Dallas 2018) (en banc). The law of appellate briefing waiver now has (at least) these features:

- Waiver occurs when (a) the defendants move for summary judgment on two grounds that each are an “independent basis” for judgment (limitations and release), (b) the trial court grants the motion without specifying a reason, and (c) “[o]n appeal, the plaintiff challenged the validity of the release in question but did not address the defendants’ statute-of-limitations argument.” In this situation, the trial court’s judgment “must stand, since it may have been based on a ground not specifically challenged by the plaintiff and since there was no general assignment that the trial court erred in granting summary judgment.” Malooly Bros., Inc. v. Napier, 461 S.W.2d 119 (Tex. 1970).

- Waiver does not occur when – and a court may thus request supplemental briefing if that would be helpful – when the defendants seek dismissal based on two doctrines (standing and ecclesiastical abstention), the substance of which “significantly overlaps.” The supreme court found such an “overlap” in Flakes when consideration of both doctrines required review of the applicable church bylaws and church membership situation. Two other examples cited in Flakes involve arguments about equitable relief related to points about money damages (First United Pentecostal Church v. Parker, 514 S.W.3d 214 (Tex. 2017)), and an issue about the applicability of a specific case in a broader dispute about the right to terminate a lease (Rohrmoos Venture v. UTSW DVA Healthcare, 578 S.W.3d 469 (Tex. 2019)).

- Supplemental briefing is discretionary under Flakes; cf. Horton v. Stovall, No.18-0925 (Tex. Dec. 20, 2019) (finding that an appellant should have been given the opportunity to cure the particular record-citation issues identified in that case).

“We are bound by this Court’s prior precedent requiring exceptionally strict compliance with rule 52.3(j)’s requirements. To comply with prior opinions of this Court that interpret mandamus rules, relators should use the exact words of rule 52.3(j) without deviation in their certification: ‘I have reviewed the petition and concluded that every factual statement in the petition is supported by competent evidence included in the appendix or record.’ Because Mr. Stewart failed to use the precise words in the rule, we are bound by precedent to deny mandamus.” In re Stewart, No. 05-19-01338-CV (Jan. 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

“We are bound by this Court’s prior precedent requiring exceptionally strict compliance with rule 52.3(j)’s requirements. To comply with prior opinions of this Court that interpret mandamus rules, relators should use the exact words of rule 52.3(j) without deviation in their certification: ‘I have reviewed the petition and concluded that every factual statement in the petition is supported by competent evidence included in the appendix or record.’ Because Mr. Stewart failed to use the precise words in the rule, we are bound by precedent to deny mandamus.” In re Stewart, No. 05-19-01338-CV (Jan. 24, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added).

Underscoring its 2019 opinion in RWI Construction v. Comerica Bank, the Fifth Court reminded that “the ancient and controlling rule forecloses resort to injunctive relief simply to sequester a source of funds to satisfy a future judgment.” Acknowledging that the “general rule would not control where there is a logical and justifiable connection between the claims alleged and the acts sought to be enjoined, or where the plaintiff claims a specific contractual or equitable interest in the assets it seeks to freeze,” it found no such connection here: “Lake Point has not established any right to the funds in Renovation Guru’s Bank of America account.Instead, this injunction mirrors the RWI injunction on general capital call funds, which served only the improper purpose of assuring future satisfaction of a subsequent judgment.” Renovation Gurus, LLC v. Lake Point Assisted Living, LLC, No. 05-19-00499-CV (Jan. 29, 2020) (mem. op.).

Underscoring its 2019 opinion in RWI Construction v. Comerica Bank, the Fifth Court reminded that “the ancient and controlling rule forecloses resort to injunctive relief simply to sequester a source of funds to satisfy a future judgment.” Acknowledging that the “general rule would not control where there is a logical and justifiable connection between the claims alleged and the acts sought to be enjoined, or where the plaintiff claims a specific contractual or equitable interest in the assets it seeks to freeze,” it found no such connection here: “Lake Point has not established any right to the funds in Renovation Guru’s Bank of America account.Instead, this injunction mirrors the RWI injunction on general capital call funds, which served only the improper purpose of assuring future satisfaction of a subsequent judgment.” Renovation Gurus, LLC v. Lake Point Assisted Living, LLC, No. 05-19-00499-CV (Jan. 29, 2020) (mem. op.).

The Fifth Court gives some highly practical guidance about the enforcement of noncompetition agreements in Gehrke v. Merritt Hawkins & Assocs.

The Fifth Court gives some highly practical guidance about the enforcement of noncompetition agreements in Gehrke v. Merritt Hawkins & Assocs.

As to the scope of activity, the Court reminded: “Covenants not to compete prohibiting solicitation of clients with whom a former salesman had no dealings are unreasonable and unenforceable. . . . . However, when an employer seeks to protect its confidential business information in addition to its customer relations, broad non-solicitation restrictions are reasonable.” Here, “the record demonstrates [Defendant] was much more than a mere salesman–he was an executive and vice president with intimate knowledge of MHA’s confidential business information and trade secrets who also supervised other salesmen.”

As to geographic scope, the Court concluded that “the trial court abused its discretion by misapplying the law to the facts in failing to enforce a geographic restriction for all states where Gehrke had worked during his final year at MHA, including the entirety of the Contested States. Additionally, we conclude the trial court abused its discretion by imposing the arbitrary ten-mile radius restriction because neither party presented evidence supporting that restriction.” No. 05-18-01160-CV (Jan. 23, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted from all quotes, all emphasis added).

In Energy Transfer Partners v. Enterprise Products Partners, the Texas Supreme Court resolves a Texas-sized partnership dispute in favor of contractual waivers of partnership. No. 17-0862 (Tex. Jan. 31, 2020). The underlying case arose from a $550 million judgment entered in 2014 in Dallas County, later reversed by the Dallas Court of Appeals; this opinion affirms the Fifth Court’s judgment.

Lovern sued Eagleridge Operating for injuries suffered in a gas line rupture. Eagleridge named Aruba Petroleum as a responsible third party; the Fifth Court found no abuse of discretion in striking that designation. The panel majority concluded that Aruba could not be liable based on the premises-liability analysis in Occidental Chemical v. Jenkins, 478 S.W.3d 640 (Tex. 2016). In re Eagleridge Operating, No. 05-19-01171-CV (Jan. 24, 2020) (mem. op.). A dissent reached a different conclusion, arguing that “[t]he majority opinion’s logic is flawed because it ignores the fact a person can simultaneously act in two different legal capacities that produce distinct legal rights and responsibilities.”

The Fifth Court reversed the denials of several special appearances in a high-profile securities case, when the plaintiffs “explicitly allege that their causes of action under sections 11 and 12 are ‘based solely on negligence and/or strict liability,'” and thus had the burden to prove only the “adverse facts that existed at the time” of the relevant offerings and its effect on the underlying business. The Court concluded that the “operative facts” related to those particular issues “are not substantially connected to Texas.” 05-19-01177-CV (Jan. 26, 2020) (mem. op.) (applying, inter alia, Moncrief Oil v. Gazprom, 414 S.W.3d 142 (Tex. 2013)).

On rehearing of Goldberg v. EMR (USA Holdings) Inc., the Fifth Court implemented the Texas Supreme Court’s December 2019 Creative Oil opinion and found that relevant communications did not adequately implicated issues of public concern to receive the TCPA’s protection: ‘The e-mails were communications because they were made by Defendants and submitted to the purchasers and suppliers. The communications were “made in connection with” “an issue related to . . . a good, product, or service in the marketplace,” scrap metal. However, all these communications were private communications between private parties about purely private economic matters. Therefore, these communications were not “made in connection with a matter of public concern” under the TCPA.’ No. 05-18-00261-CV (Jan. 23, 2020) (on motion for rehearing) (emphasis added). The Court reached a similar conclusion about other such business tort claims in Gehrke v. Merritt Hawkins & Assocs., LLC, No. 05-19-00026-CV (Jan. 17, 2020) (mem. op.)

On rehearing of Goldberg v. EMR (USA Holdings) Inc., the Fifth Court implemented the Texas Supreme Court’s December 2019 Creative Oil opinion and found that relevant communications did not adequately implicated issues of public concern to receive the TCPA’s protection: ‘The e-mails were communications because they were made by Defendants and submitted to the purchasers and suppliers. The communications were “made in connection with” “an issue related to . . . a good, product, or service in the marketplace,” scrap metal. However, all these communications were private communications between private parties about purely private economic matters. Therefore, these communications were not “made in connection with a matter of public concern” under the TCPA.’ No. 05-18-00261-CV (Jan. 23, 2020) (on motion for rehearing) (emphasis added). The Court reached a similar conclusion about other such business tort claims in Gehrke v. Merritt Hawkins & Assocs., LLC, No. 05-19-00026-CV (Jan. 17, 2020) (mem. op.)

PandaLand sought mandamus relief from the trial court’s grant of a new trial based on application of the Craddock factors. While mandamus jurisdiction has expanded for some types of new-trial grant, the Fifth Court denied relief here, stating: “Mandamus review of a trial court’s order granting a new trial is limited to orders that are void or set aside a jury verdict.” In re Pandaland Holding (HK) Ltd., No. 05-19-01259-CV (Jan. 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

PandaLand sought mandamus relief from the trial court’s grant of a new trial based on application of the Craddock factors. While mandamus jurisdiction has expanded for some types of new-trial grant, the Fifth Court denied relief here, stating: “Mandamus review of a trial court’s order granting a new trial is limited to orders that are void or set aside a jury verdict.” In re Pandaland Holding (HK) Ltd., No. 05-19-01259-CV (Jan. 17, 2020) (mem. op.).

In this election year, the State Bar’s Judicial Poll has special significance – if you have not voted yet and can’t locate the email from the Bar about it, just click here for your ballot by February 4.

In this election year, the State Bar’s Judicial Poll has special significance – if you have not voted yet and can’t locate the email from the Bar about it, just click here for your ballot by February 4.

“Extrinsic evidence not before the trial court at the time of the default judgment may be considered in a motion-for-new-trial or bill-of-review proceeding, but it cannot be considered in a restricted appeal. Accordingly, even though the attachments to appellants’ notice of appeal and the documents from the other case are papers on file in this appeal, they are extrinsic evidence that cannot be considered in determining whether there is error on the face of the record.” Convergence Aviation, Inc. v. Onala Aviation, LLC, No. 05-19-00067-CV (Jan. 2, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted). This includes an affidavit about whether the defendant in fact had a Texas registered agent, making service on the Secretary of State inappropriate.

Torres v. Lee offers three points to remember about deemed admissions:

Torres v. Lee offers three points to remember about deemed admissions:

- “Failure to obtain a ruling on the motion for leave to file late responses precludes complaint of the action of the trial court in deeming the requests for admission admitted” (citations omitted);

- A lack of good cause can be found when: “Upon receipt of the trial court’s order, Torres could have promptly filed a motion to withdraw admissions. Instead, he waited to file his motion to strike until the defendants filed their motion for summary judgment—over six months later and just two weeks before the scheduled trial date”;

- Undue prejudice can be found when: “Over six months later and just two weeks before the scheduled trial date, the defendants filed their motions for summary judgment based on the pleadings, Torres’s deemed admissions, and the trial court’s order with respect to the admissions. Defendants’ motions finally motivated Torres to file his motion to strike”

No. 05-18-00631-CV (Jan. 3, 2020) (mem. op.)

“Appellants argue, with some logical force, that the ‘tolling’of limitations in a fraudulent concealment case involving silence by a physician and hospital does not end when the patient is discharged from the hospital or at the patient’s last visit to a physician, but instead ‘runs until the plaintiff discovers the fraud or reasonabl[y] could discover the fraud.’ This is so, they say, because limitations naturally runs from the date of last treatment, so fraudulent concealment estoppel provides no additional benefit to plaintiffs like them. Unfortunately, appellants cite no authority for that proposition and we have found none.When appellants’ relationships with Dr. Courtney and Baylor Frisco terminated, so did those health care providers’ duty to disclose. Thus, the statute of limitations as to Dr. Courtney and Baylor Frisco began to run at that time.” Tarrant v. Baylor Scott & White Med. Center-Frisco, No. 05-18-01129-CV (Jan. 15, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added, citations omitted).

“Appellants argue, with some logical force, that the ‘tolling’of limitations in a fraudulent concealment case involving silence by a physician and hospital does not end when the patient is discharged from the hospital or at the patient’s last visit to a physician, but instead ‘runs until the plaintiff discovers the fraud or reasonabl[y] could discover the fraud.’ This is so, they say, because limitations naturally runs from the date of last treatment, so fraudulent concealment estoppel provides no additional benefit to plaintiffs like them. Unfortunately, appellants cite no authority for that proposition and we have found none.When appellants’ relationships with Dr. Courtney and Baylor Frisco terminated, so did those health care providers’ duty to disclose. Thus, the statute of limitations as to Dr. Courtney and Baylor Frisco began to run at that time.” Tarrant v. Baylor Scott & White Med. Center-Frisco, No. 05-18-01129-CV (Jan. 15, 2020) (mem. op.) (emphasis added, citations omitted).

“[T]the county court issued the writ of possession on July 10, and Brenham vacated the Property on or about July 14. Brenham did not testify at trial that she abandoned the Property as a direct consequence of the triggering acts; however, she testified she vacated after the writ of possession issued:

“[T]the county court issued the writ of possession on July 10, and Brenham vacated the Property on or about July 14. Brenham did not testify at trial that she abandoned the Property as a direct consequence of the triggering acts; however, she testified she vacated after the writ of possession issued:

[Counsel]: And finally a writ of possession was issued, and you moved out of the premises?

[Brenham]: Yes.

. . . Viewing the evidence under the appropriate standard, we conclude there is no evidence Brenham abandoned the Property as a direct consequence of the triggering acts. Instead, the record establishes the opposite: that Brenham vacated only after being lawfully evicted.” Kemp v. Brenham, No. 05-18-01377-CV (Jan. 14, 2020) (mem. op.)

“‘[M]andamus is governed largely by equitable principles, and“a petition for mandamus may be denied under the equitable doctrine of laches if the relator has failed to diligently pursue the relief sought,’ . . . ‘[E]quity aids the diligent and not those who slumber on their rights.’ However, laches does not apply when the order subject to the mandamus proceeding is void. To the extent [Petitioner]’s issues establish that the turnover order, and the subsequent clarification order, are void, mandamus is proper in this case.” Goin v. Crump, No. 05-18-00307-CV (Jan. 8, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).

“‘[M]andamus is governed largely by equitable principles, and“a petition for mandamus may be denied under the equitable doctrine of laches if the relator has failed to diligently pursue the relief sought,’ . . . ‘[E]quity aids the diligent and not those who slumber on their rights.’ However, laches does not apply when the order subject to the mandamus proceeding is void. To the extent [Petitioner]’s issues establish that the turnover order, and the subsequent clarification order, are void, mandamus is proper in this case.” Goin v. Crump, No. 05-18-00307-CV (Jan. 8, 2020) (mem. op.) (citations omitted, emphasis added).